by Bruce Wells | Nov 9, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

“I look forward to hearing anything your knowledgeable AOGHS community can tell me about my rather mysterious AC-ME Pocket Calculator.”

David Rance of Sassenheim, Netherlands, has collected a lot of slide rules — the analog calculating devices that became obsolete when handheld electronic calculators gained widespread use in the early 1970s. Rance and others like him have preserved “pocket calculator” collections around the world. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Nov 8, 2025 | Offshore History

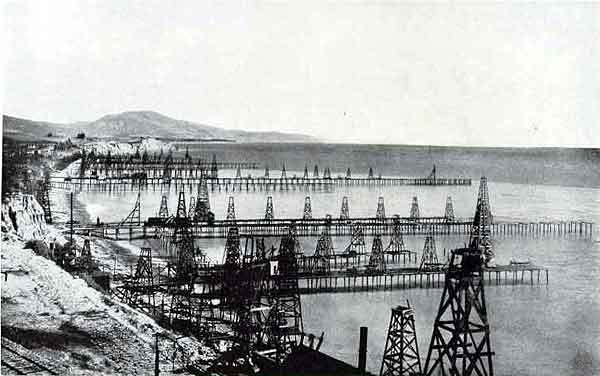

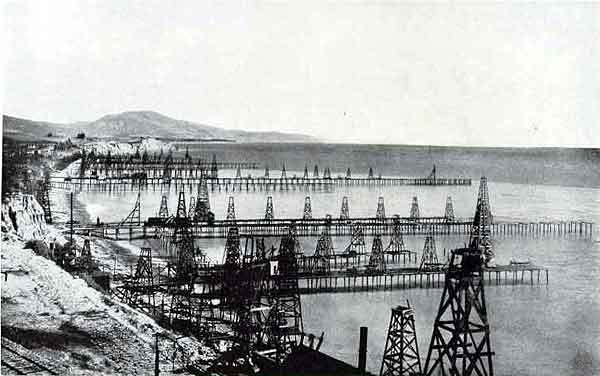

The U.S. offshore drilling for oil began in the late-19th century on lakes and at the ends of Pacific Ocean piers. Until an innovative Kerr-McGee drilling platform in 1947, no offshore drilling company had ever risked drilling beyond the sight of land.

Many of the earliest offshore oil wells were drilled from piers at Summerland in Santa Barbara County, California. Circa 1901 photo by G.H. Eldridge courtesy National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration.

In 1896, as enterprising businessmen pursued California’s prolific Summerland oilfield all the way to the beach, the lure of offshore production enticed Henry L. Williams and his associates to build a pier 300 feet out into the Pacific — and mount a standard cable-tool rig on it. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Nov 7, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

New York, Manhattan, Metropolitan, Municipal, Knickerbocker and Harlem gas companies merged in 1884.

The history of Con Edison includes stories of work crews from New York City’s many competing gas companies digging up lines of rivals — and literally battling for customers, giving rise to the term “gas house gangs.” (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Nov 5, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

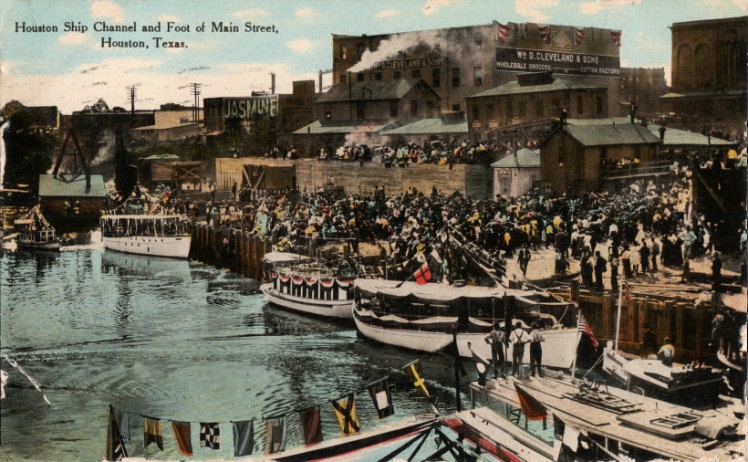

President Woodrow Wilson in 1914 opened a maritime project to support petrochemicals.

The Houston Ship Channel, the “port that built a city,” opened for ocean-going vessels on November 10, 1914, making Texas home to a world-class commercial port. President Woodrow Wilson saluted the occasion from his desk in the White House by pushing an ivory button wired to a cannon in Houston.

The Houston Ship Channel opened on November 10, 1914, as an ocean-vessel waterway linking Houston, the San Jacinto River, and Galveston Bay. 1950 postcard courtesy Boston Public Library.

The National Anthem played from a barge in the center of the Turning Basin as Sue Campbell, daughter of Houston Mayor Ben Campbell, sprinkled white roses into the water, according to a Port of Houston historian.

An 1915 image of the Houston Ship Channel that had been dredged to a depth of 25 feet. Photo courtesy Fort Bend Museum, Richmond, Texas.

“I christen thee Port of Houston; hither the boats of all nations may come and receive a hearty welcome,” Campbell proclaimed.

The bayou had been used to ship goods to the Gulf of Mexico as early as the 1830s. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) described the original waterway — known as Buffalo Bayou — as “swampy, marshy and overgrown with dense vegetation.”

“Steamboats and shallow-draft vessels were the only boats able to navigate the complicated channel,” noted ASCE, adding that in 1909, Harris County citizens formed a navigation district (an autonomous governmental body for supervising the port) and issued bonds to fund half the cost of dredging the channel.

Army engineers dredge and maintain the Houston Ship channel for deepwater shipping. It terminates about four miles east of downtown Houston. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

According to the Port of Houston Authority of Harris County, in 1937 the steamship Laura traveled from Galveston Bay up Buffalo Bayou to what is now Houston.

The steamship Laura’s trip — in water no deeper than six feet — proved the bayou was navigable by “sizable vessels” and established a commercial link between Houston and ports around the world

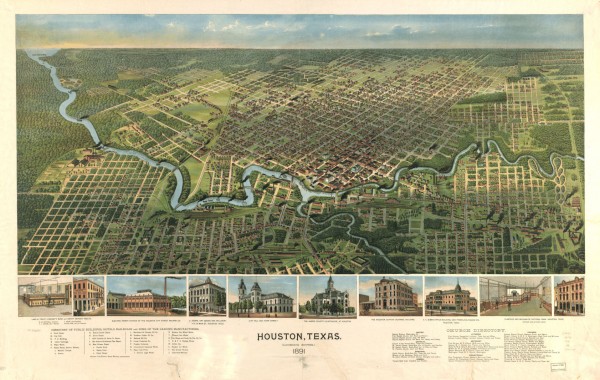

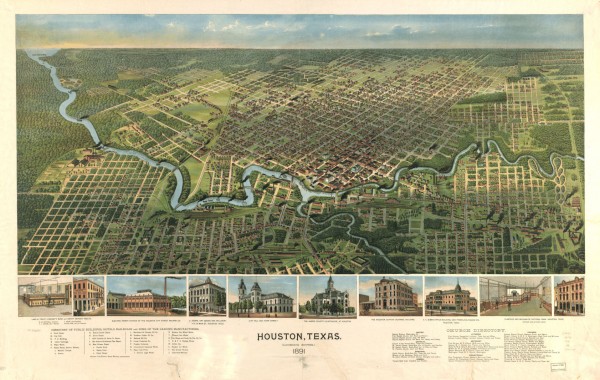

A bird’s eye view of Houston in 1891. Today’s Port of Houston is ranked first in foreign cargo and among the largest ports in the world. Map image courtesy Library of Congress Panoramic Maps.

“With the discovery of oil at Spindletop in 1901 and crops such as rice beginning to rival the dominant export crop of cotton, Houston’s ship channel needed the capacity to handle newer and larger vessels,” reported the Port Authority, administrator of the channel.

Harris County voters in January 1910 overwhelmingly approved dredging their ship channel to a depth of 25 feet for $1.25 million. The U.S. Congress provided matching funds. As work began in 1912, similar giant maritime projects included construction of the Panama Canal and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway.

An oil museum in Beaumont, Texas, includes petroleum science and refinery exhibits for educating young people about the Port of Houston. Photo courtesy Texas Energy Museum.

By 1930, eight refineries were operating along the deep water channel, ASCE notes. The area eventually supported massive petrochemical complexes along the shoreline of processing facilities and oil refineries, including ExxonMobil’s Baytown Refinery.

Under continuous development since its original construction, the Houston Ship Channel has been extended to reach 52 miles with a depth of 45 feet and a width of up to 530 feet. It travels from the Gulf through Galveston Bay and up the San Jacinto River, ending four miles east of downtown Houston.

Although the dredging vessel Texas first signaled by whistle the channel’s completion on September 7, 1914, the official opening date has remained when Sue Campbell sprinkled her white roses and President Wilson remotely fired his cannon.

With refineries and expanded liquefied terminals for exporting natural gas (LNG), the Texas waterway has grown into one of the largest petrochemical facilities in the world.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Sheer Will: The Story of the Port of Houston and the Houston Ship Channel  (2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 – Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title – “Houston Ship Channel of 1914.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/houston-ship-channel. Last Updated: November 7, 2025. Original Published Date: November 25, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 5, 2025 | Petroleum in War

Secret WWII project sent Oklahoma drillers to British oilfield, adding one million barrels of oil production by 1944.

As the United Kingdom fought for its survival during World War II, a team of American oil drillers, derrickhands, roustabouts, and motormen secretly boarded the converted troopship HMS Queen Elizabeth in March 1943. Once their story was revealed years later, they would become known as the Roughnecks of Sherwood Forest.

The 42 volunteers from Noble Drilling and Fain-Porter Drilling companies taken before they secretly embarked for the United Kingdom on March 12, 1943, aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth, which had been converted into a troop transport. Photo courtesy Guy Woodward Collection, American Heritage Center.

By the summer of 1942, the situation was desperate. The future of Great Britain — and the outcome of World War II — depended on the supply of petroleum. At the end of that year, demand for 100-octane fuel had grown to more than 150,000 barrels every day — and German U-boats ruled the Atlantic.

British Secretary of Petroleum, Geoffrey Lloyd in August 1942 called for an emergency meeting of his country’s Oil Control Board to assess the “impending crisis in oil.” (more…)