by Bruce Wells | Jun 26, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Oilfield discoveries at El Dorado and Smackover in the 1920s launched the Arkansas petroleum industry.

Arkansas oil wells of the 1920s created boom towns, established the state’s petroleum exploration and production industry, and boosted the career of a young wildcatter named Haroldson Lafayette Hunt.

The first Arkansas well that yielded “sufficient quantities of oil” was the Hunter No. 1 of April 16, 1920, in Ouachita County, according to the Arkansas Geological Survey. Natural gas was discovered a few days later in Union County by Constantine Oil and Refining Company.

Surrounded by 20 acres of woodlands, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in the Smackover oilfield preserves the state’s petroleum history seven miles north of equally historic El Dorado.

A January 1921 well drilled in the same Union County field at El Dorado marked the true beginning of commercial oil production in Arkansas. When the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well struck oil in 1921, the oilfield discovery soon catapulted the population of El Dorado from 4,000 to 25,000 people. The well, 15 miles north of the Louisiana border, was the state’s first commercial oil well.

“Twenty-two trains a day were soon running in and out of El Dorado,” noted the Arkansas Gazette. An excited state legislature announced plans for a special railway excursion for lawmakers to visit the oil well in Union County.

Meanwhile, Haroldson Lafayette “H.L.” Hunt arrived from Texas with $50. He joined the crowd of lease traders and speculators at the Garrett Hotel, where fortunes were being made — and lost. Hunt launched his start as an independent oil and natural gas producer during the El Dorado drilling boom.

Some locals said it was his expertise at the poker table that earned him enough to afford a one-half acre parcel lease where his Hunt-Pickering No. 1 well produced some oil, but ultimately proved unprofitable.

Hunt persevered, and within four years acquired substantial El Dorado and Smackover oilfield holdings. By 1925, he was a successful 36-year-old oilman with his wife Lyda and three young children living in a three-story El Dorado home. He would significantly add to his oilfield successes a decade later in Kilgore, Texas (learn more in East Texas Oilfield Discovery).

Giant Oilfield at El Dorado

Located on a hill a little over a mile southwest of El Dorado, the derrick was visible from the town, according to historians A.R. and R.B. Buckalew. They write that three “gassers” had been completed in the general vicinity, but did not produce in commercial quantities.

There was no market for natural gas at the time, the authors explained in their 1974 book, The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924.

The Garrett Hotel, where H.L. Hunt checked in with 50 borrowed dollars and launched his long career as a successful independent oil producer.

Yet Dr. Samuel T. Busey was convinced “there was oil down there somewhere.”

The authors added, “Among those who gambled their savings with Busey at this time were Wong Hing, also called Charles Louis, a Chinese laundry man, and Ike Felsenthal, whose family had created a community in southeast Union County in earlier years.”

With no oil production nearby, investing in the “wildcat” well was a leap of faith. Chal Daniels, who was overseeing drilling operations for Busey, contributed the hefty sum of $1,000. On January 10, 1921, the well had been drilled to 2,233 feet and reached the Nacatoch Sand. A small crowd of onlookers and the drilling crew — after moving a safe distance away — watched and listened.

“The spectators, among them Dr. Busey, watched with an air of expectancy,” noted the historians. “Drilling had ceased and bailing operations had begun to try to bring in the well. At about 4:30 p.m., as the bailer was being lifted from its sixth trip into the deep hole, a rumble from deep in the well was heard.”

The rumbling grew in intensity, “shaking the derrick and the very ground on which it stood as if an earthquake were passing,” the authors report. “Suddenly, with a deafening roar, ‘a thick black column’ of gas and oil and water shot out of the well,” they added.

The gusher blew through the derrick and “bursts into a black mushroom” cloud against the January sky. The Busey No. 1 well produced 15,000,000 to 35,000,000 cubic feet of gas and from 3,000 to 10,000 barrels of oil and water a day.

Petroleum brings Prosperity

Thanks to the El Dorado discovery, the first Arkansas petroleum boom was on. By 1922, there were 900 producing wells in the state.

Civic leaders raised funds to preserve El Dorado’s historic downtown – and add an Oil Heritage Park at 101 East Main Street.

“Three months after the Busey well came in, work was underway on an amusement park located three blocks from the town that would include a swimming pool, picnic grounds, rides and concessions,” noted the Union County Sheriff’s Office. “Culture was not forgotten as an old cotton shed in the center of town near the railroad tracks was converted to an auditorium.”

The 68-square-mile field will lead U.S. oil output in 1925 – with production reaching 70 million barrels. “It was a scene never again to be equaled in El Dorado’s history, nor would the town and its people ever be the same again,” the authors concluded. “Union County’s dream of oil had come true.”

In 2002, El Dorado gathered 40 local artists to paint 55 oil drums donated by the local Murphy Oil Company. Preserving the town’s historic assets, including boom-era buildings, remains a major goal of the local group, Main Street El Dorado, which was the “2009 Great American Main Street Award Winner” of the National Trust Main Street Center.

Second Oil Boom: Discovery at Smackover

Prior to the January 1921 El Dorado discovery, the region’s economy relied almost exclusively on the cotton and timber industries “that thrived in the vast virgin forests of southern Arkansas.”

Petroleum wealth helped Smackover, Arkansas, incorporate in 1922.

Six months after the Busey-Armgstrong No. 1, another giant oilfield discovery 12 miles north will bring national attention – and lead to the incorporation of Smackover. A small agricultural and sawmill community with a population of 131, Smackover had been settled by French fur trappers in 1844. They called the area “Sumac-Couvert,” meaning covered with sumac or shumate bushes.

According to historian Don Lambert, by 1908 Sidney Umsted operated a large sawmill and logging venture two miles north of town. He believed that oil lay beneath the surface. “On July 1, 1922, Umsted’s wildcat well (Richardson No. 1) produced a gusher from a depth of 2,066 feet,” Lambert reported.

“Within six months, 1,000 wells had been drilled, with a success rate of ninety-two percent. The little town had increased from a mere ninety to 25,000 and its uncommon name would quickly attain national attention,” added Lambert.

Roughnecks photographed following the July 1, 1922, discovery of the Smackover (Richardson) field in Union County. Courtesy of the Southwest Arkansas Regional Archives.

The oil-producing area of the Smackover field covered more than 25,000 acres. By 1925, it had become the largest-producing oil site in the world. The field will produce 583 million barrels of oil by 2001.

Opened in 1986, the Arkansas Natural Resources Museum educates visitors in the heart of the historic Smackover oilfield. Exhibits explain how the Busey No. 1 well near El Dorado “blew in with a gusty fury” in January 1921.

The museum includes a five-acre Oilfield Park with operating examples of early and modern oil-producing technologies. They can be found one mile south of the once petroleum-rich town of Smackover, which has celebrated its petroleum heritage with an “Oil Town Festival” every June.

Abundant natural gas in the Fayetteville shale formation brought more drilling to Arkansas.

With more than 46,800 wells drilled between 1925 and 2023, about one-third of the 75 Arkansas counties have produced oil and or natural gas, reported Mineralsanswers.com in July 2024.

Southern Arkansas also is considered among the most prolific lithium resources of its type in North America, according to ExxonMobil, which in 2023 acquired the rights to 120,000 gross acres of the Smackover formation.

Fayetteville Shale

Thanks to advances in drilling technologies combined with hydraulic fracturing, the Fayetteville Shale — a 50-mile-wide formation across central Arkansas — has added vast natural gas reserves while creating a new petroleum boom for the state.

Unlike traditional fields containing hydrocarbons in porous formations, shale holds natural gas in a fine-grained rock or “tight sands.” Until the 1990s, drilling in most shale formations was not considered profitable for production.

Surrounded by 20 acres of lush woodlands, the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources collects and exhibits southern Arkansas petroleum – along with the history of brine drilling and the salt industry. It also has documented the social and economic histories that accompanied the 1920s oil boom.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920-1924 (1974); The Three Families of H. L. Hunt (1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1989); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery

(1982); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Arkansas Oil Wells.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/arkansas-oil-and-gas-boom-towns. Last Updated: January 3, 2025. Original Published Date: April 21, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 20, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

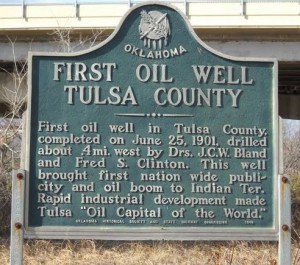

Pennsylvania wildcatters discovered an oilfield in 1901 near Tulsa in the Creek Nation, Indian Territory.

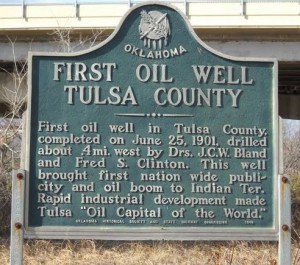

In 1901, six years before Oklahoma statehood, discovery of the Red Fork oilfield south of Tulsa began the town’s journey to becoming the “Oil Capital of the World.” Discovery of the giant Glenn Pool in 1905 helped.

Attracted to Indian Territory following an 1897 discovery at Bartlesville (see First Oklahoma Oil Well) two experienced drillers from the Pennsylvania fields found oil in the Creek Indian Nation on June 25, 1901. They drilled using steam boilers powering cable-tool derricks, the technology used to drill the first U.S. oil well in 1859 along Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Dedicated during the 2007 Oklahoma centennial, a circa 1950s derrick commemorates the June 25, 1901, Red Fork oilfield discovery well. Photo courtesy Route 66 Historic Village.

After leasing thousands of acres in the Creek Nation, John S. Wick and Jesse A. Heydrick spudded their remote wildcat well near the village of Red Fork, across the Arkansas River from Tulsa. The attempt to find oil was not easy for the Pennsylvanians.

At the time, “Oklahoma Indian lands were in the process of being transferred from communal tribal ownership to individual tribal member holdings,” noted Bobby D. Weaver in a 2010 article for the Oklahoma Historical Society.

“This process, which made legal access to Indian property very uncertain, kept most oilmen away from areas under Indian control,” Weaver added. The well was almost never drilled when the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway station agent at Red Fork, “refused to accept a draft on their Pennsylvania backers to release their drilling equipment.”

Creek Land lease

The exploratory well was saved by a loan from two local doctors, John C. W. Bland and Fred S. Clinton. Drilling began at Red Fork on the tribal allotment of Sue A. Bland, a Creek citizen and wife of Dr. Bland.

Oil and natural gas exploration, production and service companies rushed to open offices in Tulsa following the 1901 oilfield discovery — and another in 1905.

Although the Sue A. Bland No. 1 well erupted an oil geyser high into the air, the discovery soon settled into production of just 10 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 537 feet. Despite the low production, the Oklahoma Territory well attracted a lot of national attention, drawing large numbers of exploration companies to the Tulsa area.

The Tulsa Democrat newspaper exclaimed, “Geyser of Oil Spouts at Red Fork” and “Oil Well Gusher Fifteen Feet High.” Within a week, Red Fork – once a quiet town of 75 people – was overrun by people clamoring for leases.

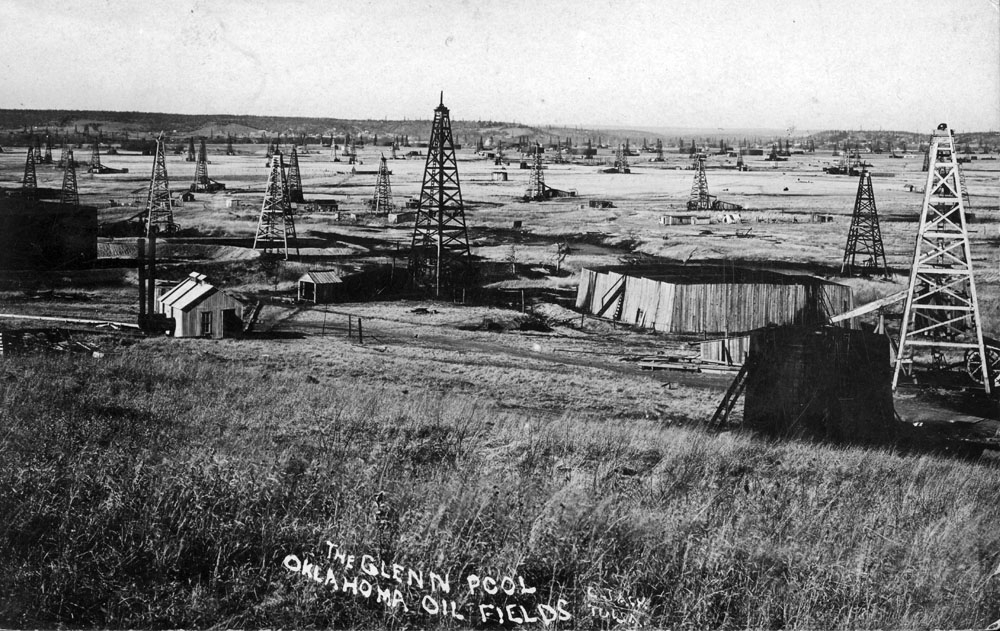

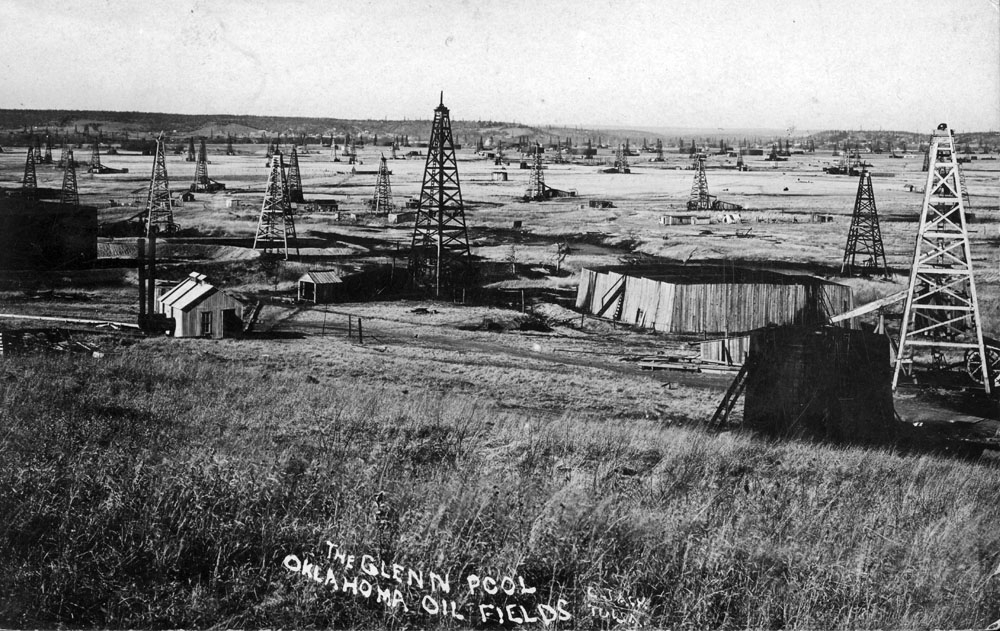

Tulsa County’s 1901 oilfield discovery was followed in 1905 by a well drilled deeper than the Red Fork production sands to reveal the far bigger Glenn Pool field (above in 1909). Photo courtesy Tulsa Historical Society & Museum.

Many of the newcomers settled in Tulsa, which in 1904 constructed its first bridge across the Arkansas River to accommodate wagonloads of oilfield workers and equipment.

“The Red Fork discovery never produced a great amount of oil, with most of the wells being in the fifty-barrel-per-day range, but it did produce excitement and drilling activity,” concluded Weaver.

“The discovery also prompted Tulsa citizens to begin a strong promotional campaign, with the result that by 1904 a much-needed bridge had been built across the Arkansas River,” he added. “This gave Tulsa access to the Red Fork Field and beyond and started that community on the road to becoming the predominant oil city in Oklahoma.”

The city’s petroleum industry future was assured in 1905 when a well drilled deeper than the Red Fork production sands revealed a truly massive oilfield. The Glenn Pool’s production far exceeded Tulsa County’s earlier Red Fork discovery.

Learn more in Making Tulsa the Oil Capital.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Tulsa Oil Capital of the World, Images of America (2004); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry

(2004); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry (1980); Oil in Oklahoma

(1980); Oil in Oklahoma (1976). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1976). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “Red Fork Gusher.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/oklahoma-red-fork-oilfield. Last Updated: June 21, 2025. Original Published Date: June 23, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 19, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Cemetery generated royalty checks to next-of-kin when oil was drawn from beneath family plots.

In the summer of 1921, the Signal Hill oil discovery would help make California the source of one-quarter of the world’s entire oil output. Soon known as “Porcupine Hill,” the town’s Long Beach oilfield produced about 260,000 barrels of oil a day by 1923.

The Alamitos No. 1 well, drilled on a remote hilltop south of Los Angeles, erupted a column of “black gold” on June 23, 1921. Natural gas pressure was so great that the oil geyser climbed 114 feet into the air.

After the June 1921 oilfield discovery, Signal Hill had so many derricks that people called it Porcupine Hill. Circa 1935 postcard courtesy Boston Public Library, Digital Commonwealth.

The oilfield discovery well, which produced almost 600 barrels a day, would eventually produce 700,000 barrels of oil. Signal Hill incorporated three years after its Alamitos discovery well made headlines.

In 1923, Signal Hill’s petroleum field produced more than 68 million barrels of oil. The community of Signal Hill later became one of the first U.S. cities to be surrounded by another city, Long Beach.

Signal Hill, a residential area before the 1921 discovery of the Long Beach oilfield, became covered in derricks. “Today you can see wonderful commemorative art displays of this era throughout the lush parks and walkways of Signal Hill,” notes a local newspaper.

By the 2000s, more than one billion barrels of oil were pumped from the Long Beach oilfield since the original 1921 strike. “Signal Hill is the scene of feverish activity, of an endless caravan of automobiles coming and going, of hustle and bustle, of a glow of optimism,” reported California Oil World.

Signal Hill circa 1930 — at the corner of 1st Street and Belmont Street. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Museum of Natural History.

“Derricks are being erected as fast as timber reaches the ground,” the magazine adds. “New companies are coming in overnight. Every available piece of acreage on and about Signal Hill is being signed up.”

Signal Hill helped make California the source of one-quarter of the world’s oil. “Porcupine Hill” and the Long Beach field produced 260,000 barrels of oil a day by 1923.

Within a year, Signal Hill — before and after a residential area — will have 108 wells, producing 14,000 barrels of oil a day. There were so many derricks, people started calling it Porcupine Hill. “Derricks are so close that on Willow Street, Sunnyside Cemetery graves generated royalty checks to next-of-kin when oil was drawn from beneath family plots,” noted one historian.

Derricks were so close to one cemetery that graves “generated royalty checks to next-of-kin when oil was drawn from beneath family plots.” By 1923, production would reach 259,000 barrels per day from nearly 300 wells. Photo is part of a panorama in the Library of Congress.

Dave Summers explained in his 2011 article, “The Oil Beneath California,” that when oilfields around Los Angeles began to develop, “Californian production became a significant player on the national stage.” The OilPrice.com article continued:

By 1923 it was producing some 259,000 barrels per day from some 300 wells, in comparison with Huntington Beach, which was then at 113,000 barrels per day and Santa Fe Springs at 32,000 barrels per day… And, in a foreboding of the future problems of overproduction, this was the first year in a decade that supply exceeded demand.

Shell Oil Geologists

Signal Hill oil potential had drawn wildcatters south of Los Angeles since 1917 but with no success. Two Royal Dutch Shell Oil Company geologists and a driller persevered.

“This was a great exploit and economic risk for the time. Shell Oil Company had just lost $3 million at a failed drilling site in Ventura, five years before,” reported a Long Beach newspaper.

A 1954 photograph of the Alamitos No. 1 well — and the monument dedicated on May 3, 1952, “as a tribute to the petroleum pioneers for their success here…”

Although another “dry hole” would be expensive, Shell geologists Frank Hayes and Alvin Theodore Schwennesen spudded their well in March 1921. Driller O.P. “Happy” Yowells believed oil lay deeper than earlier “dusters” had attempted to reach.

By summer the steam-powered cable tool rig had Yowells close to making oilfield history. On June 23, 1921, at a depth of 3,114 feet, his wildcat well for Shell Oil erupted, revealing a petroleum reserve that extended to nearby Long Beach.

According to the Paleontological Research Institution, Signal Hill became the biggest oil field the already productive Southern California region had ever seen. This made California, “the nation’s number-one producing state, and in 1923, California was the source of one-quarter of the world’s entire output of oil!”

Decades before Signal Hill, another giant southern California oilfield had been discovered in 1892. A struggling prospector drilled into tar seeps he found near present-day Dodger Stadium (see Discovering Los Angeles Oilfields).

Signal Hill Oil Park

Today, Signal Hill’s Discovery Well Park includes a community center to educate the public. Historic photos and descriptions can be found at six viewpoints along the Panorama Promenade. There are producing oil wells throughout the hill — with the historic “Discovery Well, Alamitos Number 1” at the corner of Temple Avenue and East Hill Street.

A monument dedicated on May 3, 1952, serves “as a tribute to the petroleum pioneers for their success here, a success which has, by aiding in the growth and expansion of the petroleum industry, contributed so much to the welfare of mankind.”

Visitors to the area can see “wonderful commemorative art displays of this era throughout the lush parks and walkways of Signal Hill,” reported the Long Beach Beachcomber. Dedicated on September 30, 2006, the statue “Tribute to the Roughnecks” can be found on Skyline Drive.

“Tribute to the Roughnecks” by Cindy Jackson stands atop Signal Hill. Long Beach is in the distance. Signal Hill Petroleum Chairman Jerry Barto and Shell Oil employee Bruce Kerr are depicted in bronze.

The first California oil wells were drilled near oil seeps in the northern part of the state around the time of the Civil War. These Pico Canyon wells produced limited amounts of crude oil, but there was no market for the oil. Larger oilfields would be revealed in the early 1890s about 35 miles to the south.

Earlier explorers noted evidence of California’s petroleum fields by the large number of oil seeps, both onshore and offshore. California’s first commercial oil well in 1876 was drilled in Pica Canyon, well known for its asphalt seeps.

Between 1913 and 1923 Hollywood used the derricks on Signal Hill in movies starring Buster Keaton and Fatty Arbuckle. In 1957, what many consider the world’s first “all jazz” radio station, KNOB (now KLAX), first transmitted from a small studio on top of the historic oil hill.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Signal Hill, California, Images of America (2006); Huntington Beach, California, Postcard History Series

(2006); Huntington Beach, California, Postcard History Series (2009); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry

(2009); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry  (2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Signal Hill Oil Boom.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/signal-hill-oil/. Last Updated: June 18, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.