Famous artworks are part of U.S. petroleum history.

Many kinds of media preserve the heritage of an industry that helped fuel, shape and define modern civilization. The American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s page about oil patch art is a sample of petroleum-related social science history that deserves wider recognition.

Museums, historians, writers, and educators preserve the heritage of the domestic petroleum industry, which began in 1859 with the first U.S. well. Many notable artists, including photographers, became recorders and interpreters of petroleum exploration and production — see for example the 1861 oil on canvas, “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania.”

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) oil on canvas painting “Gas” of 1940 includes the iconic red flying Pegasus logo of Mobilgas. Image courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In addition to “oil painters,” this AOGHS website features illustrators, cartoonists, and other artists while maintaining a researchers’ resources page with links to colleges, universities, and collections at the Smithsonian Institution and the Library of Congress.

Rouseville 1861 Oil Well Fire

An early oil well tragedy would lead to new technologies — and a work of art. Sometimes called “Oil Well Fire Near Titusville” but more accurately, Rouseville, the early oilfield tragedy was overshadowed by the greater tragedy of the Civil War.

A painting by James Hamilton of the 1861 oil well fire that killed Henry Rouse is in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

“Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” by James Hamilton (circa 1861), was on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in 2018. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Alley Oop’s Oil Roots

The Depression-era comic strip caveman Alley Oop began in the imagination of a cartoonist who drew Permian Basin oilfield maps. The West Texas oil town of Iraan today proclaims itself as Victor Hamlin’s inspiration. His idea for the comic strip, which in the 1930s ran in 800 newspapers, was inspired by working in the company town’s Yates oilfield, where he developed a life-long interest in geology and paleontology.

Centennial Oil Stamp Issue

Pennsylvania artist Robert Foster won the competition for a centennial oil stamp commemorating the birth of America’s petroleum industry. The stamp was issued on August 27, 1959, by U.S. Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield, who proclaimed, “The American people have great reason to be indebted to this industry.”

With 120 million stamps to follow the first day of issue, the stamp served “as a reminder of what can be achieved by the combination of free enterprise and the vision and courage and effort of dedicated men.”

Meet Joe Roughneck

Since 1955, a small, bronze Joe Roughneck bust is presented once a year as the petroleum industry’s Chief Roughneck Award, honoring someone “whose character represents the highest ideals of the industry.”

Originally created by noted artist Torg Thompson – and presented to each Chief Roughneck recipient, Joe Roughneck began life in Lone Star Steel Company print advertising. The character became popular and was soon adopted by the industry at large, prompting Lone Star Steel to declare, “Joe doesn’t belong to us anymore. He’s as universal as a rotary rig.”

Mobil’s High-Flying Trademark

A winged neon reminder of its oil heritage once soared above Dallas on the Magnolia Petroleum building. Today, the carefully refurbished red-winged oil patch icon continues to be a city attraction perched on a 22-foot derrick in front of the Omni Dallas Hotel. Mobil Oil Company’s trademark has been a feature of Dallas since first welcoming attendees to a 1934 petroleum convention. It remains among the most recognized corporate symbols in American history.

Oil Art of Graham, Texas

Depression-Era artist Alexandre Hogue’s “Oil Fields of Graham” was restored and displayed at the Old Post Office Museum & Art Center. One of his 1937 paintings depicts a Pecos oilfield with storage tanks in the foreground and the quarters for workers in the background. Hogue’s popular “Dust Bowl” collection was featured in Life magazine.

Alexandre Hogue’s 1939 mural “Oil Fields of Graham” is preserved in the Old Post Office Museum & Art Center in Graham, Texas.

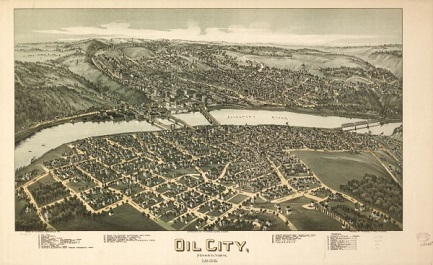

Oil Town “Aero Views”

Traveling from Pennsylvania to Texas at the turn of the century, Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler created town “aero views” or “bird’s eye views” – panoramic maps of many of America’s earliest petroleum communities. More than 400 Thaddeus Fowler panoramas have been identified.

There are 324 in the Library of Congress, including petroleum towns like Oil City, Pennsylvania; Wichita Falls, Texas; Tulsa, Oklahoma; and many others.

Seuss I am, an Oilman

Thirty years before the Grinch stole Christmas in 1957, Theodore Seuss Geisel’s critters could be seen in Standard Oil of New Jersey advertising campaigns. During the Great Depression, the future Dr. Seuss promoted Essolube and other products. His “Seuss Navy” Essomarine booth at the 1936 National Motorboat Show was phenomenally successful. Seuss later said his experience at Standard, “taught me conciseness and how to marry pictures with words.”

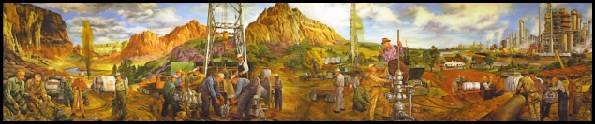

Smithsonian’s Hall of Petroleum

In June 1967, an entire wing of exhibits – the “Hall of Petroleum” – opened at a Smithsonian Institution museum on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Welcoming visitors was the “Panorama of Petroleum,” a 56-foot mural by Delbert Jackson of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

A 56-foot mural in 1967 welcomed visitors to the Smithsonian’s Museum of History and Technology.

Smithsonian exhibits included cable-tool and rotary drilling rigs, pump jacks and other oilfield exhibits. For museum visitors, the mural served as a guide to the equipment contents of the museum’s petroleum exhibits.

“Smokesax” Art has Pipeline Heart

In early 1993, Bob “Daddy-O” Wade created a 63-foot tall saxophone sculpture at Billy Blues Bar & Grill on Houston’s west side. His artwork included two 48-inch steel sections of petroleum pipeline to create what some call the largest (non-playable) saxophone in the world.

_______________________________

The federal program also produced many outstanding histories by skilled photographers; several featured life oilfields. View the PDF from a 2010 AOGHS presentation: Russell Lee Oklahoma Oilfields.

A replica circa 1870s standard cable-tool derrick and engine house educate visitors to the Penn-Brad Oil Museum in Custer City, Pennsylvania. Photo by Bruce Wells.

AOGHS research links include photography resources found at universities and the Library of Congress, in addition to petroleum history videos and a limited selection of books and authors.

_______________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells.