Drilling of a remote wildcat well began in late 1950. The blizzard came in January.

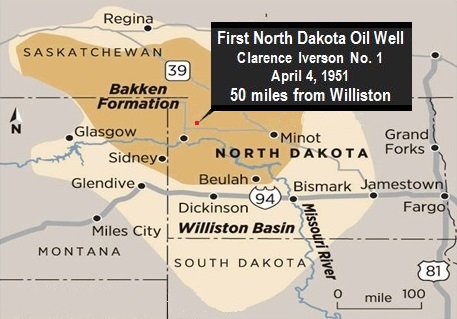

Drillers of a remote wildcat well in Clarence Iverson’s wheat field northeast of Williston endured a North Dakota winter before finding oil on April 4, 1951. Their discovery launched the Williston Basin drilling boom.

At about one in the morning on April 4, after four months of hard drilling and with snow piled high from recent blizzards, the Clarence Iverson No. 1 well produced oil. Amerada Petroleum’s 1951 discovery — the first commercial oil well in North Dakota — would reveal a prolific petroleum basin stretching from North and South Dakota, Montana, and into Canada.

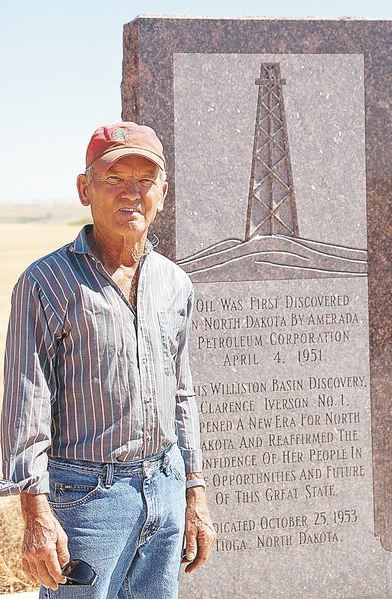

Dedicated in 1953, a granite marker commemorates the Clarence Iverson No. 1 well, which had two years earlier discovered the 134,000-square-mile Williston Basin on Iverson’s farm.

After decades of dry holes drilled from one corner of North Dakota to the other, new technologies and true tool-pusher grit brought the state’s first oil discovery in 1951.

Although this wildcat drilling attempt had been regarded with great skepticism, within two months of the strike 30 million acres were under lease. A 2008 article in the Bismarck Tribune, quoted Sid Anderson, the former state geologist, who was a college student at the University of North Dakota when oil was discovered.

Cliff Iverson stands by a monument on the family farm in Tioga, North Dakota, in August 2008. The monument marks the April 4, 1951, oil discovery on his late father’s farm.

“It was brand new, then, and pretty exciting times,” Anderson recalled. The amber-colored oil in the area was of such high quality, “you could have run a diesel with it straight from the well.”

“This was the first major discovery in a new geologic basin since before World War II,” James Key declared in Word and Picture Story of Williston and Area.

By 1952, Standard Oil of Indiana was building a 30,000 barrel per day refinery, he notes. Forty-two oilfield service and supply companies had opened offices in Williston. In June, Service Pipeline Company announced it would build a pipeline to the Standard refinery.

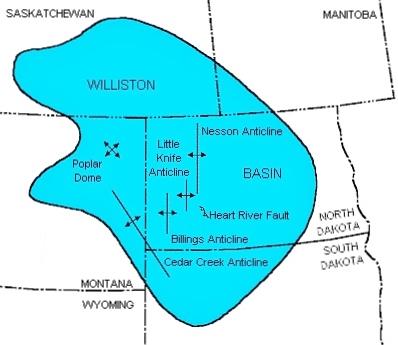

Key added that although the Williston Basin is named after the city of Williston, it was first exposed in 1912 by Dr. W.T. Thom, Jr. , “a sophomore studying geology when he happened into a creek bed in the area of the Cannonball River. It was his discovery of coral that led him to believe that the area was once inundated by an ancient sea.”

On June 17, 2014, North Dakota oil production surpassed one million barrels per day thanks to development of the Bakken shale formation in the western part of the state.

State officials reported North Dakota produced 1,001,149 barrels of oil a day from a record 10,658 wells. Industry journalists, proclaiming the milestone a sign America was freeing itself from foreign oil, referred to the state as “Saudi Dakota.”

North Dakota Dry Holes

The earliest permit issued for oil exploration in North Dakota came from the state geologist in 1923. By the late 1930s, petroleum companies were working with a growing North Dakota Geological Survey to improve the science behind exploration, which often featured difficult formations, including granite, thwarting drilling technologies of the day.

According to historian Clarence Herz, despite repeated failures, companies continued to come to North Dakota and spend large amounts of money on leases and drilling. “There were no indications from any of the wells they drilled that they were even close to production, but that did not deter them,” said Herz, adding that the expensive lessons brought many positive developments.

“A more skilled labor force and continuous technological innovation that included the use of explosives, acid and newly invented scientific instruments meant an acceleration of the drilling process as wells were not only being drilled faster, but deeper and at a much higher cost,” Herz explained.

The 1951 well that launched North Dakota’s first oil boom was drilled by Amerada Petroleum. Today, a gas processing plant operates not far from the discovery well northeast of Williston.

One such invention came from two Frenchman, Conrad and Marcel Schlumberger,” he added. “Schlumberger was fast becoming a household name in the oil industry for the development of an electrical resistivity well log created by the French brothers in 1927.

Although it failed to find oil in the 1930s, the California Oil Company used technological and scientific breakthroughs like rotary drilling and seismometers to reach a depth previously unheard of in the state. A well spudded in October 1937 had to be abandoned in August 1938 when the drill pipe twisted off in the hole almost two miles deep. Attempts to “fish” the pipe failed.

California Oil Company’s failure did not stop exploration in other areas of the state, Herz said, citing a report noting that most major oil companies sent men to North Dakota to investigate — and buy leases. It took the Carter Oil Company three months with modern equipment to drill nearly 5,000 feet in 1940 without finding oil. Two years later the company still had not found it.

Following World War II, Herz noted that “from one corner of the state to the other, companies leap-frogged one another in anticipation of being the first to identify an oil producing zone.”

Leasing about 1.5 million acres, Continental Oil Company worked with the Pure Oil Company trying to find a North Dakota oilfield in the spring of 1949. In September 1950, Magnolia Petroleum became the latest company to drill a North Dakota dry hole.

The Magnolia wildcat well reached a depth of 5,556 feet, found granite, and was plugged and abandoned. Soon others came to North Dakota with large drilling rigs.

1951 Discovery Well

Despite exploration costs, the dry holes were not looked at as failures, but as learning experiences with valuable geologic and technical knowledge gained from each attempt.

An independent oilman and investor, Thomas W. Leach was a former chief geologist for an Oklahoma oil company who was convinced oil could be found. In the late 1930s, he had convinced Standard Oil Company of California to drill a well that reached a depth of 10,281 feet.

The site Leach suggested did not find any oil — costing Standard Oil almost a million dollars.

In 1950, geologist Thomas W. Leach convinced Amerada Petroleum of Tulsa that oil could be found in North Dakota’s Nesson Anticline.

After World War II, where he served as a Captain of U.S. Army Artillery, Leach returned to North Dakota and continued leasing land. The geologist eventually convinced Amerada Petroleum of Tulsa that success could be found in the Nesson Anticline about 50 miles northeast of Williston.

A site was selected on Clarence Iverson’s family farm near Tioga and drilling began on September 3, 1950, Herz reported. There was little to report until January 1951, “except the depth of the bit, the conditioning of the mud, and the occasional tripping pipe.”

Following a January 29 blizzard that shut down the well, drilling continued until total depth — 11,744 feet — was reached on February 4, 1951. No oil was found. It was decided to try “shooting” the well.

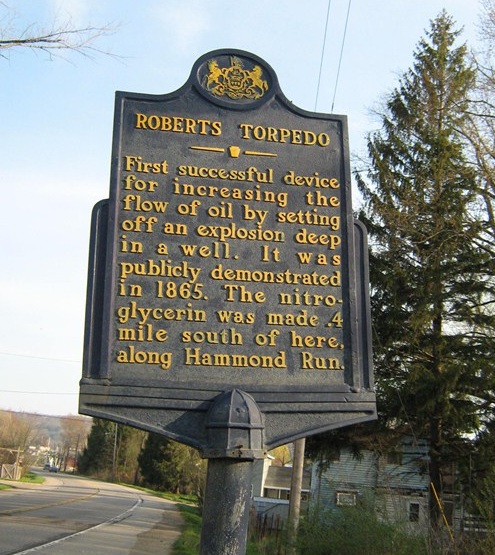

A Pennsylvania historical marker commemorates the “Roberts Torpedo.”

“The practice of perforating a well, or using explosives to perforate the rock, is not new,” says Herz. Colonel Edward A. L. Roberts first used his “Roberts Torpedo” in 1865. The practice was successful and soon the dry holes of Pennsylvania were turned into producers by blasting wells with nitroglycerin torpedoes (see Shooters — A “Fracking” History).

Advancements to improve oil and natural gas production came from the invention of a Downhole Bazooka to perforate well casings. The Clarence Iverson No. 1 well was “shot” from 11,706 feet to 11,729 feet using a Lane-Wells Company “Koneshot,” but still no oil was found.

According to Herz, perforation became a standard practice whereby multiple charges attached to a gun were lowered into the well’s casing. Once into place the charges were fired, perforating the well at small intervals, hopefully releasing the oil from the rock.

“The Koneshot was a type of perforating gun that used a shaped charge. It was another innovation,” Herz explained. He added that charges had “a spiral placement in a steel housing at a three-inch centerline distance from each other.”

The arrangement was an improvement over some of the early perforators (learn more about perforating with shaped charges in Downhole Bazooka).

Work on the Iverson well was again halted the week of March 5 by another blizzard. The well would remain idle for several weeks until the snow choked roads could be cleared for passage. With the well plugged back to a depth of 11,669 feet, the work stopped to make repairs and prepare for another perforation.

The State Historical Society of North Dakota preserves a Williston newspaper’s photo of the Clarence Iverson No. 1 drilling rig surrounded by snow.

The well was again perforated, this time from 11,630 feet to 11,640 feet with four holes per foot. At 12:55 a.m. on April 4, 1951, the Clarence Iverson No. 1 began producing about 240 barrels of oil a day. The state of North Dakota finally had its first discovery well.

According to a 2008 Associated Press article, at first Clarence Iverson wasn’t pleased when seismologists exploded dynamite in his wheat fields looking for oil. His son Cliff, who was 20 when oil was found on the family farm, remembers his father smiling when oil surfaced.

“He worried a lot about his water wells,” Cliff said of his father. The farm became one of the biggest tourist attractions in the Upper Midwest after oil was discovered there. “They came from as far as Minnesota and all over North Dakota and Montana,” he added. “People knew it was history in the making, and it changed a lot of people’s lives.”

The Clarence Iverson No. 1 well alone produced 585,000 barrels of oil. Clarence Iverson died in 1986, a wealthy man “who never got used to all that money.”

The Bakken Shale

The earliest producing wells of the Bakken shale formation were drilled in the early 1950s on Henry O. Bakken’s farm less than five miles from the Clarence Iverson No. 1 well. Occupying about 200,000 square miles within the Williston Basin, the oil shale of the Bakken formation may be the largest domestic oil resource since Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay, according to many experts. But efforts to extract shale oil using conventional vertical wells was difficult.

“The Clarence Iverson well produced from the Silurian, Duperow and Madison formations, but not the Bakken, according to Kathy Neset, a geologist who moved to Tioga from New Jersey in 1979. “There are several oil-producing formations at different depths within the larger Williston Basin.”

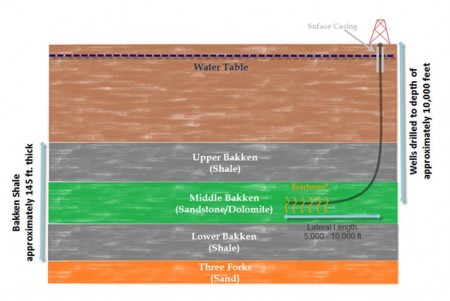

The Bakken shale play consists of three layers, according to the Energy Policy Research Foundation, Inc. The middle sandstone layer is what is commonly drilled and fractured.

The Bakken formation frustrated a lot of geologists for years, “because they knew the oil was there but they didn’t have the technology to extract the oil,” Neset explained in a 2012 Mitchell Republic newspaper article, “Famous Bakken Formation Named For North Dakota Homesteaders.”

The Bakken formation first produced in 1953 from a well named after Henry Bakken, the landowner. Like the Williston discovery well, it was also drilled by Amerada Petroleum. This first shale well was on the Nesson Anticline, later known as a Bakken “sweet spot,” home to natural fractures in the rock, according to the Energy Policy Research Foundation.

Although North Dakota has been an oil producing state since 1951, only during the past decade has the Bakken oil boom made it the fourth largest oil producing state in the country and one of the largest onshore plays in the United States.

“The Bakken is a shale oil play. It is conventional, light-sweet crude oil, trapped 10,000 feet below the surface within shale rock,” the foundation noted (also see Ute Oil Company — Oil Shale Pioneers). The shale consists of three layers — an upper layer of shale rock, a middle layer of sandstone/dolomite, and a lower layer of shale rock. The middle sandstone layer is what is commonly drilled and fractured.

“Production was mainly from a few vertical wells — until the 1980s when horizontal technology became available,” added a 2008 article in the Oil Drum. “Only recently after the intensive application of horizontal wells combined with hydraulic fracturing technology did production really take off.”

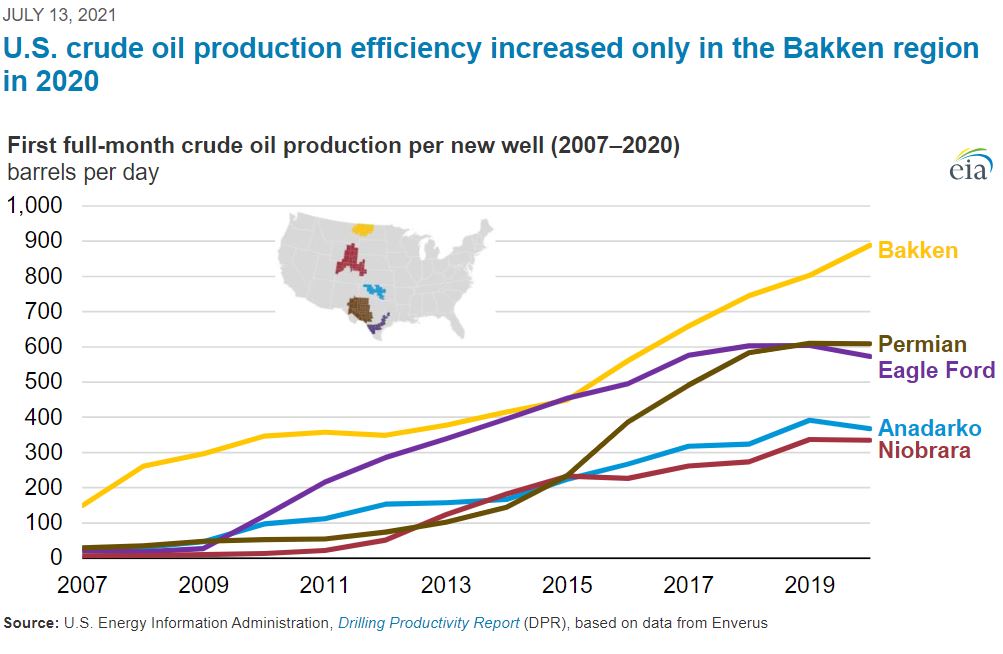

Well production efficiency in the Bakken region increased significantly in 2020, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in 2008 estimated 3.0 billion barrels to 4.3 billion barrels of undiscovered oil in America’s portion of the Bakken formation, elevating it to a “world-class” accumulation. The survey’s assessment of the shale’s potential was a 25-fold increase in the amount of “technically recoverable” oil compared to the agency’s 1995 estimate of just 151 million barrels of oil.

According to state statistics from 2010, oil production from the Bakken in North Dakota had steadily increased from about 28 million barrels in 2008, to 50 million barrels in 2009 to approximately 86 million barrels. In 2020, initial oil production per well — well production efficiency — increased significantly in the Bakken region, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

In December 2021, a USGS estimate for the Bakken and Three Forks Formations in the Williston Basin of Montana and North Dakota included 4.3 billion barrels of unconventional oil and 4.9 trillion cubic feet of unconventional natural gas in the two formations.

As Secretary of the Interior Ken Salaza earlier predicted, “The Bakken formation is producing an ever-increasing amount of oil for domestic consumption while providing increasing royalty revenues to American Indian tribes and individual Indian mineral owners in North Dakota and Montana.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Bakken Goes Boom: Oil and the Changing Geographies of Western North Dakota (2016); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First North Dakota Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/north-dakota-williston-basin. Last Updated: March 30, 2025. Original Published Date: March 31, 2014.