Texas well disaster of 1933 helped bring advancements in directional drilling.

A Depression-era disaster in a giant oilfield near Conroe, Texas, brought together the inventor of portable drilling rigs and the father of directional drilling. George E. Failing and H. John Eastman employed new technologies that allowed “the bit burrowing into the ground at strange angles.”

Early Conroe oil wells revealed shallow but “gas charged” oil-producing sands in what would prove to be the third-largest oilfield in the United States at the time. By the end of 1932, more than 65,000 barrels of oil flowed daily from 60 wells in the region north of Houston.

Disaster came in January 1933 when one of the Conroe wells blew out and erupted into flames. The runaway well then cratered, completely swallowing nearby drilling rigs.

The catastrophic fire threatened the entire field’s production. It took the combined efforts of oilfield technology innovators George Failing of Enid, Oklahoma, and H. John Eastman of Long Beach, California, to save the Conroe oilfield.

Popular Science

“Only a handful of men in the world have the strange power to make a bit, rotating a mile below ground at the end of a steel drill pipe, snake its way in a curve or around a dog-leg angle, to reach a desired objective.” — Popular Science Monthly, May 1934

While some people describe Crater Lake at Conroe, Texas, as bottomless, it is estimated to have a depth of 600 feet — with the twisted remains of the Madeley No. 1 rig at the bottom. In 1933, an out-of-control well erupted into flames and cratered, swallowing two drilling rigs.

According to witnesses, the oil burned for months and produced a towering black column that could be seen from downtown Houston 40 miles away. Conroe’s oilfield was no stranger to the dangers of extremely pressured wells, especially given the drilling technologies of the time.

In 1931, wildcatter George Strake’s South Texas Development Company No. 1 well had completed a difficult well at 4,991 feet deep, producing millions of cubic feet of natural gas per day and several hundred barrels of oil. He had found the Conroe oil sands to be highly gas-charged, shallow, and unstable.

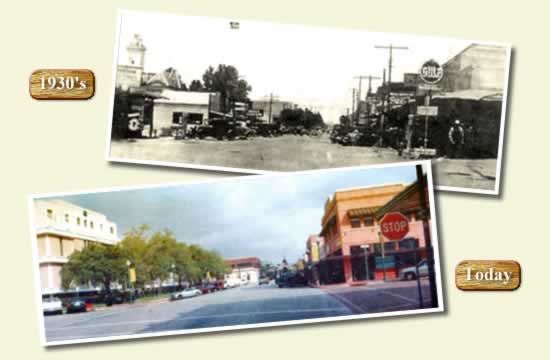

Petroleum prosperity led to the first stoplight in Conroe. A newspaper proclaimed, “Strake Well Comes In. Good for 10,000 Barrels Per Day.”

Despite the challenges, Strake continued and his company spudded a second well 2,000 feet from the first Conroe well. That well, completed on June 5, 1932, revealed the field’s main petroleum-producing formation. More successful well completions followed.

Boom Town Conroe

The Conroe Courier newspaper headline proclaimed, “Strake Well Comes In. Good for 10,000 Barrels Per Day.” Strake had found the discovery well for the 19,000-acre Conroe oilfield, but its geology made drilling and development risky.

Although Texas lawmakers regulated drilling practices, casing procedures, and well spacing, the oilfield remained a hazardous place as drilling and production technologies evolved.

By the end of 1932, Humble Oil and Refining (now ExxonMobil), the Texas Company (the future Texaco), and some independent producers operated 60 wells producing about 10,000 barrels of oil a day. Many wells required water, mud, and cement to be pumped into them for stabilization. Others required relief holes to reduce reservoir gas pressures, but drilling continued unabated.

In January 1933, it was the Standard Oil of Kansas Madeley No.1 that blew in as a gusher and immediately ignited.

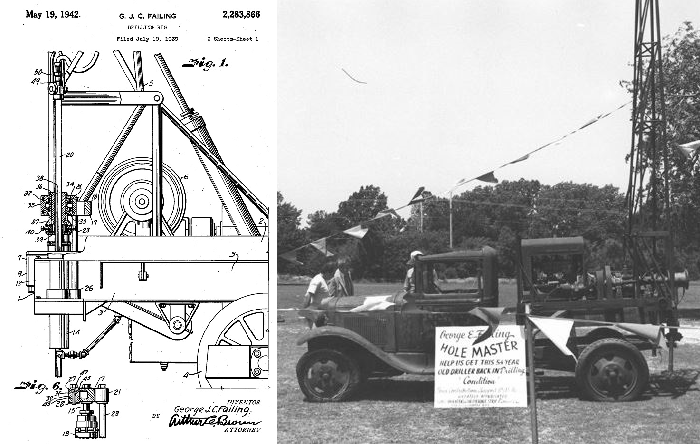

George E. Failing received a 1942 U.S. patent for an innovative portable drilling rig he had invented a decade earlier using his Ford farm truck and an assembly to transfer power from the engine to the drill. Today, his company operates a 350,000-square-foot plant in Enid, Oklahoma. Photo courtesy GEFCO.

All attempts to put out the fire with dynamite blasts and tons of dirt failed. The crater spread into a growing lake of burning oil, and the entire field was threatened. The nearby rig of James Abercrombie (and his cousin Dan Harrison) collapsed into the growing crater.

With its casing shattered, Abercrombie’s Alexander No. 1 well unleashed the reservoir’s full fury and millions of barrels of oil began surging into the crater. As the fire raged, good fortune intervened.

Failing’s Portable Rig

Coincidently, George Everett Failing Enid, Oklahoma, and his crew happened to be working near Conroe in early 1933. They arrived on the scene with their new, self-contained portable drilling rig.

Failing had begun his company only two years prior when he mated a drilling rig to a 1927 Ford farm truck and a power take-off assembly. The same engine that drove the sturdy truck across the oilfields was used to power its rotary drill.

George Failing’s portable rig drilled relief wells in record time to relieve gas pressure and put out the Conroe fire.

While a traditional steam-powered rotary rig took about a week to set up and drill a 50-foot borehole, Failing could drill ten 50-foot holes in a single day. This capacity to quickly drill multiple relief wells and relieve the enormous gas pressure was critical to extinguishing the Conroe fire.

Working behind walls of Foamite and sheets of asbestos to suppress the flames, Failing drilled nearly a dozen 600-foot relief wells in record time, enabling the firefighters to at last extinguish the inferno.

It cost Failing the hearing in one ear and partial sight in one eye, but the fire was out. It had burned for three months. A grateful Humble Oil Company paid Failing a $25,000 bonus and his success was widely reported, giving his fledgling company a welcome boost.

The George E. Failing Co. (GEFCO) facility in Enid continues to manufacture drilling rigs and other oilfield equipment used worldwide. His drilling trucks would become a feature in parades in his hometown of Enid.

Conroe Lake of Oil

Although Failing was successful and the Conroe fire was out, the growing lake of oil continued to feed off of the sunken Abercrombie and Harrison casing at the rate of over 6,000 barrels each day. Meanwhile, reduced pressure in the field dropped all other wells to less than 100 barrels per day in production.

Humble Oil Company was the largest producer in the field — and was determined to bring the well under control before it drained the field of its lifting power and dissipated the oil pool, completely destroying their investment. After the fire was out, Humble Oil brought in H. John Eastman from Eastman Oil Well Survey Co. of Long Beach, Calif., to stop the flow of oil into the crater.

H. John Eastman is recognized as the father of directional drilling and surveying in the United States.

In October, Humble purchased the “crater well” and the 15 acres surrounding it from J.S. Abercrombie Company and the Harrison Oil Company for $300,000. The astute Abercrombie and Harrison retained ownership of all oil the crater produced under the “law of capture.”

Since this oil was not charged against the field’s “allowable” production, as managed by the Texas Railroad Commission, Abercrombie and Harrison bulldozed berms around the crater and continued to pump oil out at $1.10 per barrel, making a substantial fortune.

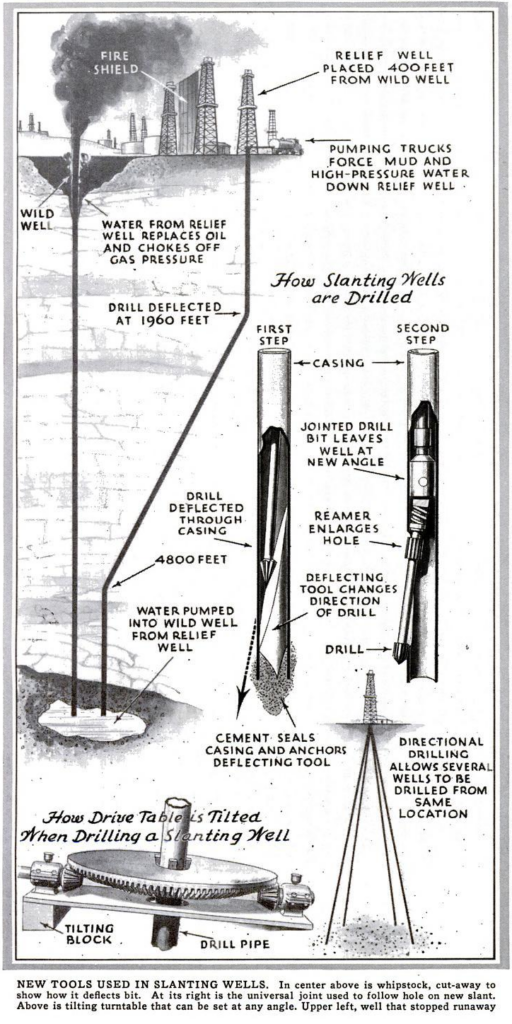

Humble Oil hired John Eastman’s company to find a way to choke off the unrestricted flow of oil into the crater. The growing dimensions of the oil-filled lake meant that the relief well would have to be spudded 400 feet away and the borehole deviated deep underground to reach the crater’s source.

Whipstock Expert

To initiate a deviation or sidetracking in drilling, whipstocks used a tapered wedge in a borehole that forced the bit into a new direction — and John Eastman was a whipstock expert.

Today widely recognized as the father of directional drilling and surveying, the 1933 Conroe disaster brought new challenges to Eastman and his drilling technique.

Drilling of the relief well began on November 12, 1933. At 1,400 feet, Eastman began his efforts to redirect the borehole. The Conroe Courier kept careful track of the relief well, reporting its progress on December 8, “Killer Well Now Drilling At 2,760 Feet.” December 29, “Conroe Relief Hole Drilling Now At 4,870.”

On January 7, 1934, Eastman’s directional drilling successfully reached its target. Four steam-powered pumps began forcing thousands of tons of water into the well under 1,400 psi pressure. After two days, the erupting oil flow was finally staunched.

George Failing’s revolutionary drilling trucks joined many a parade in his hometown of Enid, Oklahoma.

By January 19, 1934, the newspaper reported, “Conroe Crater Becoming Just Another Well.” It was a year since the Madeley No. 1 had first roared onto the scene. The newspaper’s postscript noted that the crater, “will exist only as the most expensive memory of the Conroe field.”

Additionally, “Slanted oil wells are the latest sensation of the oil industry,” began a May 1934 Popular Science Monthly article. “Drilled by experts who use special tools and secret methods to send the bit burrowing into the ground at strange angles, they are finding amazing new applications.”

New Science

The 1934 article continued: “Brilliant work by a specialist in the new science of directional drilling has just saved a whole oilfield from ruin. A spectacular wild well was spouting oil, gas, and water with volcanic fury from a huge crater more than a hundred feet across. Alexander No. 1, thundering giant of the Conroe field in Texas, was out of control.”

Further, many witnesses to the runaway well’s fate reported seeing “the whole derrick, with its Christmas tree of pipe fittings and valves, vanish into a cauldron of mud, water, and oil.”

Illustration from May 1934 Popular Science Monthly. Directional drilling pioneer John Eastman saved the Conroe oilfield.

Noting that H. John Eastman brought his new directional drilling technology to the crisis in Conroe, Popular Science reported: “With the aid of simple geometry, Eastman sketched a plan. He would sink a straight hole part way, then drift sidewise in an arc, intersecting the oil formation close to the wild well.”

After successfully using the whip stock to deflect the drilling direction, “Into the hole went a single-shot surveying instrument of Eastman’s own invention. As it hit bottom, a miniature camera within the instrument clicked, photographing the position of compass needle and a spirit-level bubble.”

“Again Eastman caused the bit to swerve like a living thing, plunging straight down to 5,135 feet. Here, at last, it struck the oil formation. Thousands of gallons of water could be pumped into the borehole. Within a few hours, the flood of oil ceased spouting from the crater. Eastman’s relief well had done its work.”

Technology Pioneers

More than just expensive memories remain from those early days of men making oil history. Wildcatter George Strake’s oil fortune continued to grow, making him a wealthy man. He gave much of his fortune to the Catholic Diocese of Galveston-Houston and to educational institutions and civic organizations and charities.

The Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center in Enid, Oklahoma, preserves George Failing’s historic portable drilling rig.

Concurrently, H. John Eastman’s contributions to the industry would continue in oilfields around the world with INTEQ, a business unit of Baker Hughes promoted for its advanced drilling technologies “for efficiency and precise well placement.”

Meanwhile, George E. Failing became widely respected in Oklahoma for his philanthropy as his Enid-based company grew into an international leader in designing and manufacturing portable drilling rigs. James Abercrombie and Don Harrison’s good fortune with the “crater well” and other ventures led them to prominence as Houston civic leaders.

Today, the Abercrombie Foundation helps fund Texas Children’s Hospital, an internationally recognized pediatric hospital located in the Texas Medical Center in Houston. A brief oral history interview with James Abercrombie is preserved at the Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member today and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: Technology and the “Conroe Crater.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/directional-drilling. Last Updated: May 20, 2025. Original Published Date: June 1, 2005.