by Bruce Wells | May 30, 2025 | Petroleum Art

Thousands of glass-negative images document the earliest scenes of America’s petroleum industry.

Soon after the first American oil well in 1859 launched the U.S. petroleum industry in remote northwestern Pennsylvania, an English emigrant began documenting life in the oilfields.

John A. Mather (1829-1915) photographed the people, places and technology from the earliest days of oil exploration. In the fall of 1860, he set up his first studio in Titusville, Pennsylvania — where he would begin to amass more than 20,000 glass-plate negatives.

Oil Creek Artist

Titusville and nearby Oil City and Franklin, in the heart of the growing Pennsylvania oil regions (soon joined by the boom town of Pithole), proved ideal locations for documenting the people, events and evolving drilling technologies of petroleum exploration and production.

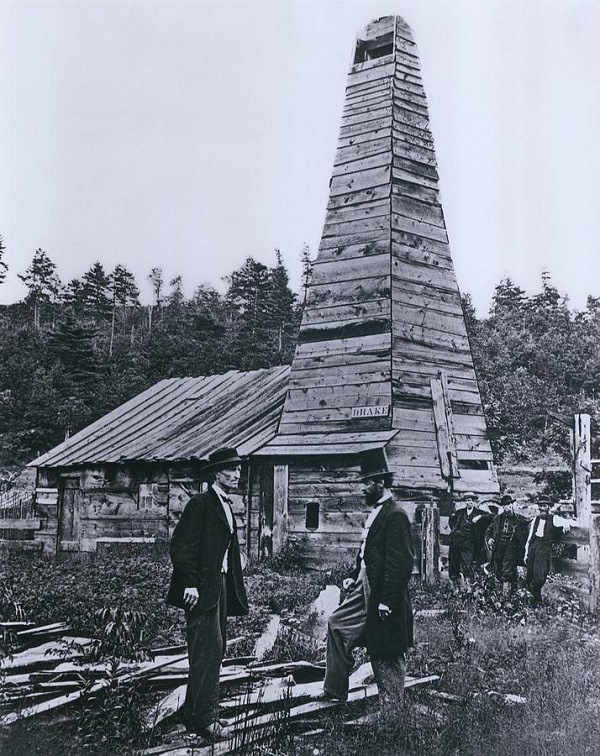

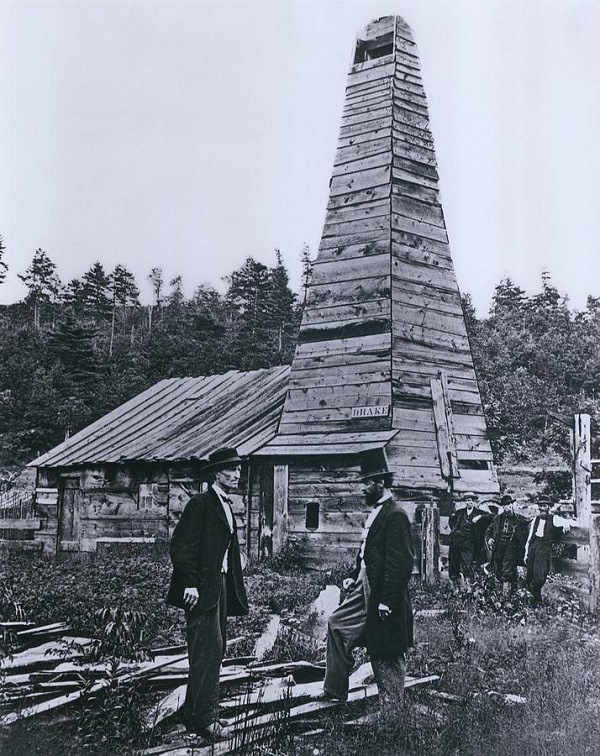

Iconic but often misidentified 1866 photo by John A. Mather features Edwin L. Drake (in top hat) with friend Peter Wilson standing at the rebuilt derrick and engine house of the 1859 first U.S. commercial oil well. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum and Park.

What Civil War photographers Matthew Brady and James Gardner documented on battlefields, Mather accomplished in Pennsylvania’s oilfields. In 1866, Titusville’s “Oil Creek Artist” photographed the now iconic image of Edwin L. Drake, standing at the original drilling site (rebuilt after the first oil well fire).

Like Brady, Mather abandoned making one-of-kind daguerreotypes and ambrotypes in favor of wet plate negatives using collodion — a flammable, syrupy mixture also called “nitrocellulose.” With one glass plate, many paper copies of an image could be printed and sold.

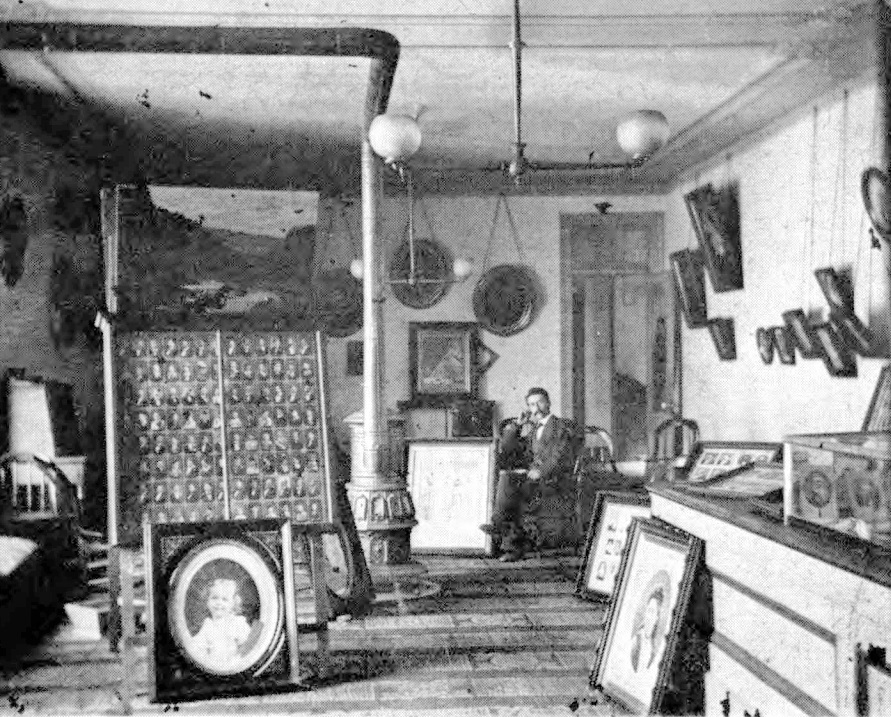

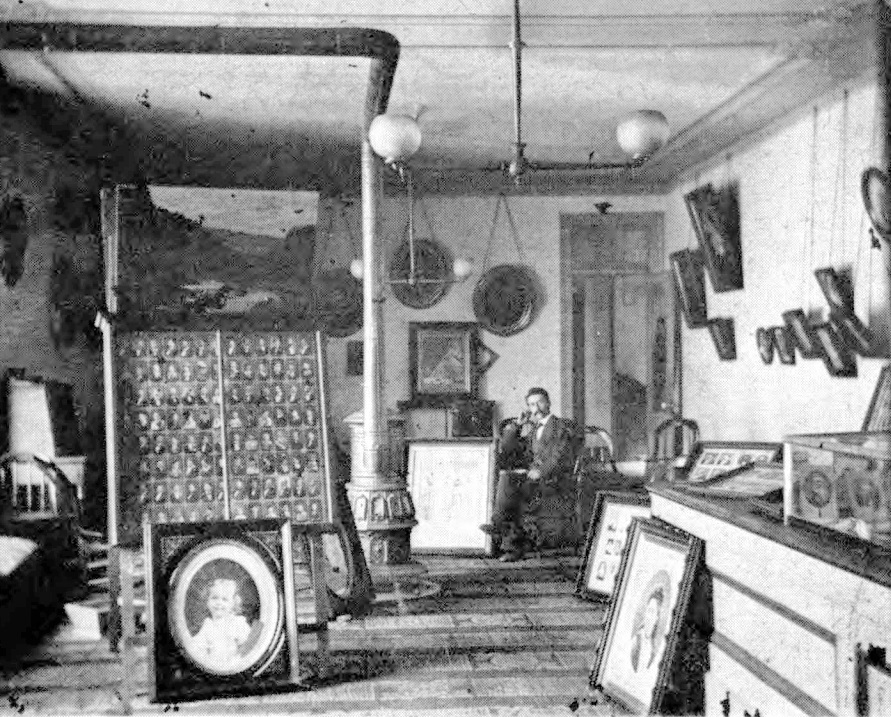

Oilfield photographer John Aked Mather, probably a self-portrait circa 1900.

However, unlike most of the era’s studio photographers, Mather transported his camera and chemicals into the industrial chaos of early Pennsylvania oilfields. But like most people in the new oil region, Mather was susceptible to “oil fever;” he hoped to drill some successful wells himself.

Oil Fever

Above all, the oil regions continued to boom. The gamble of drilling for new oilfield discoveries brought excitement. As “oil fever” spread, polka and waltz song sheets like the Petroleum Court Dance became popular.

Having narrowly missed the opportunity for a one-sixteenth share of the Sherman Well, which proved to be the “best single strike of the year,” Mather and three associates invested in oil wells near booming Pithole Creek. He proved to be better at using a camera.

John Mather photographs courtesy Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine and Drake Well Museum, Titusville. Above, the interior of his Titusville studio, circa 1865.

Mather’s investment in finding oil at Pithole Creek did not lead to producing any commercial quantities. He tried again on the Holmden Farm off West Pithole Creek. His unsuccessful drilling effort proved to be one of the last wells in the infamous boom town Pithole.

Many tried, but few in the increasingly crowded oil regions would rival the wealth of the celebrated “Coal Oil Johnny.” Years later, Mather acknowledged that the excitement of the drilling for “black gold” was so great that he “forsook photography for the oil business.”

Meanwhile, the young U.S. petroleum industry learned some hard lessons. Highly pressurized wells and disasters like the 1861 fatal Rouseville oil well fire brought attention to a new science, petroleum geology.

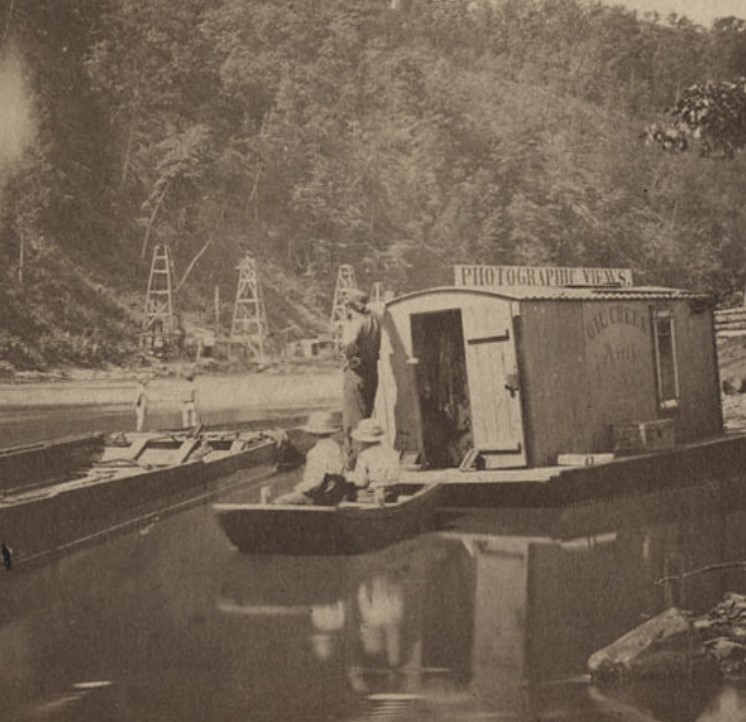

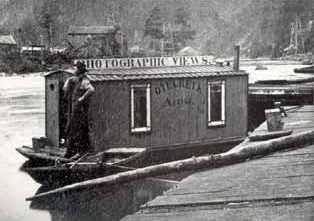

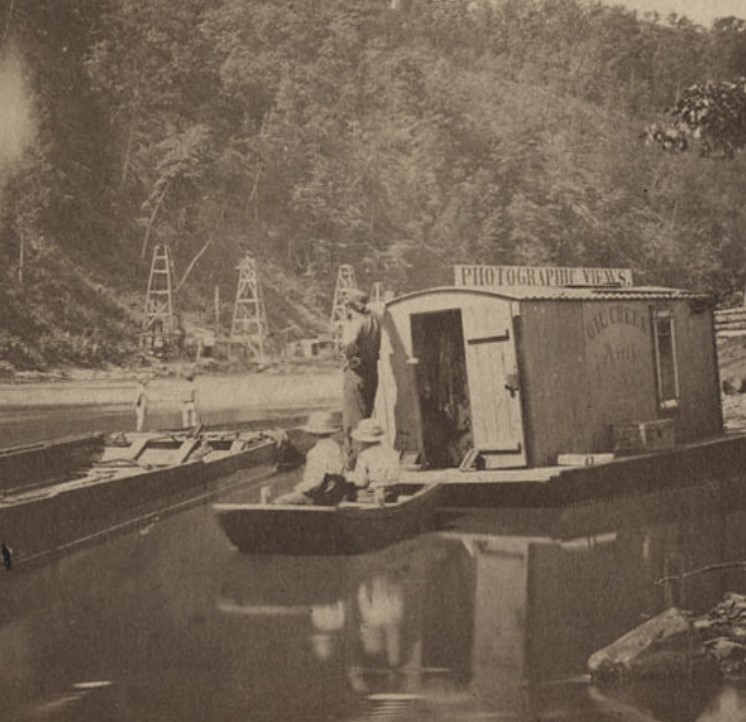

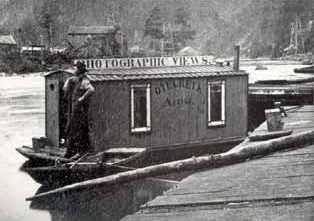

Detail from the 19th-century stereoview “Oil Regions of Pennsylvania,” published by C. W. Woodward of Rochester, N.Y., featuring John Mather’s floating studio and dark room.

Returning to the oilfields with his camera, Mather’s rolling darkroom and floating studio traveled up and down Oil Creek. In 2008, photographic historian John Craig (1943-2011) noted the discovery of a Mather image in a stereoview card published by C.W. Woodward.

“We have had the card for years and assumed that the boat belonged to Woodward,” the historian noted. “When I made the scan I noticed that the side of the boat carried a sign ‘Oil Creek Artist.’ I Googled and found that the studio/darkroom boat belonged to John A. Mather.”

At its peak, Mather’s collection amounted to more than 16,000 glass negatives. The trade magazine Petroleum Age described his oilfield photography as “so perfect in finish it stands the test of time.”

Oil Creek Flood and Fire

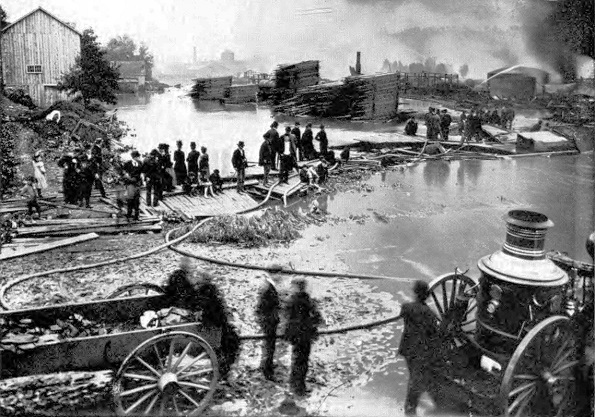

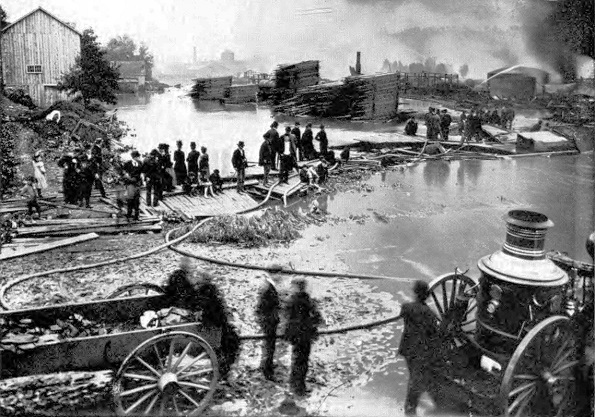

On Sunday morning June 5, 1892, and after weeks of rain, Oil Creek’s overflowing Spartansburg Dam failed at about 2:30 a.m. A wall of water and debris swelled towards Titusville and its oil works, seven miles downstream.

“On rushed the mad waters, tearing away bridge after bridge, carrying away horses, homes and people,” one newspaper reported about the flood’s devastation. Then fire erupted from ruptured benzine and oil storage tanks.

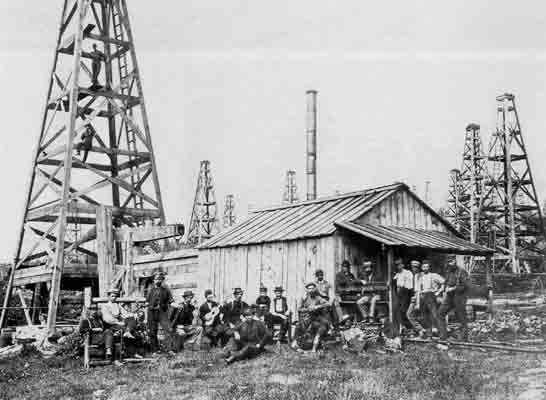

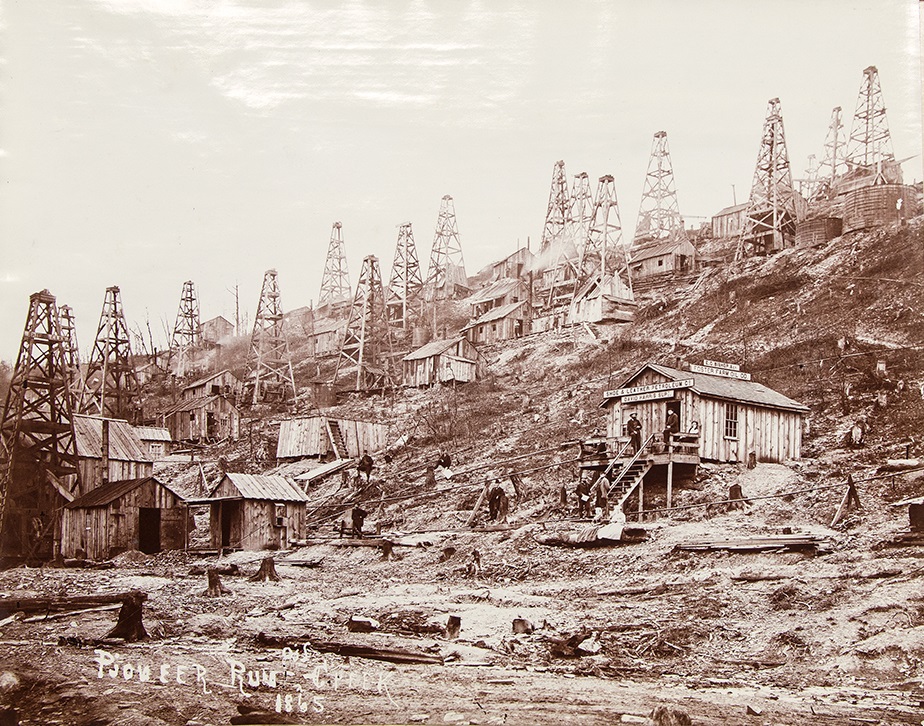

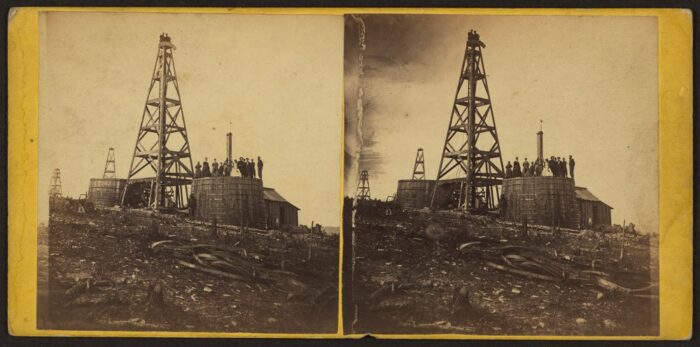

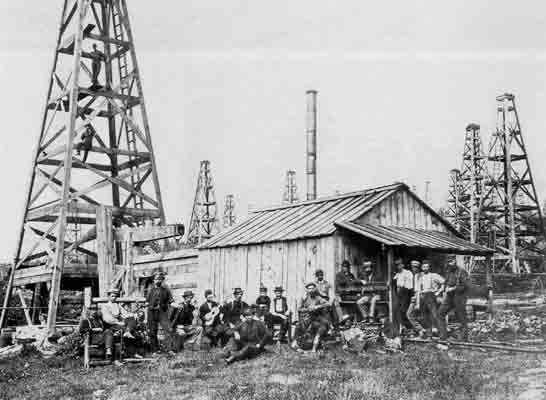

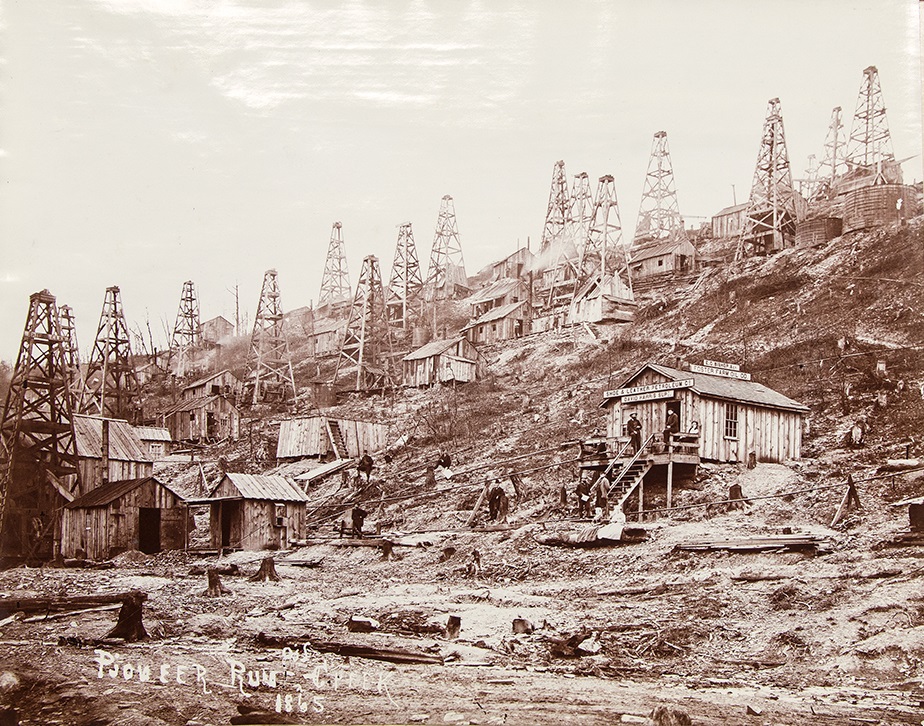

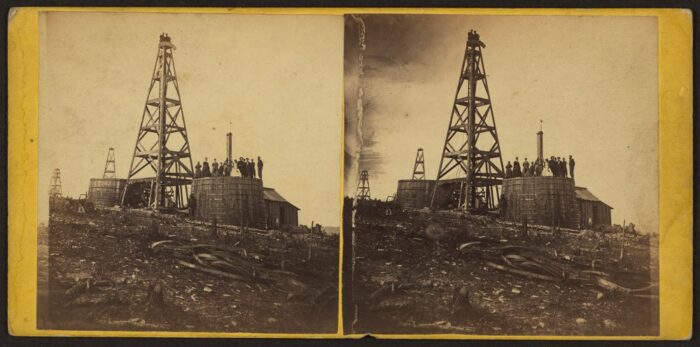

Oilfield workers pose on and among their oil derricks and engine houses in this 1864 John Mather photo from the Drake Well Museum collection in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Newspapers all over America carried stories of the disaster. In Montana, the Helena Independent headlines included: “Waters of an Overflowing Creek Become a Rushing Mass of Flames” and victims being, “Spared by the Deluge Only to Become the Prey of the Fire.”

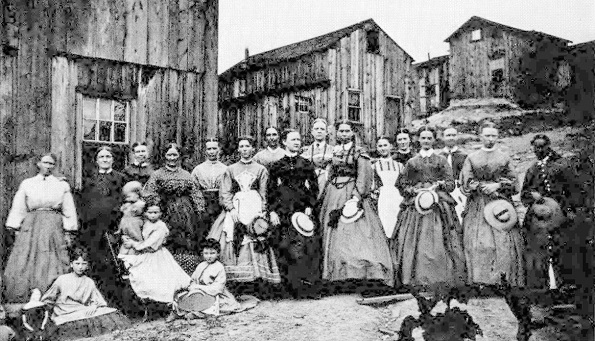

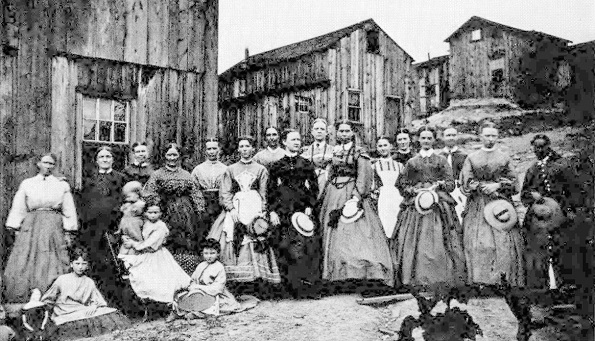

John Mather’s photographs documented family life in remote early oil boom towns. He also briefly caught “oil fever” and unsuccessfully invested in a few wells in the booming Pithole Creek field.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle added: “The Waters Subside and The Flames Die Away, Revealing the Full Extent of the Calamity.” Oil City and Titusville were “Nearly Wiped From Off the Earth.”

Unfortunately, Mather’s studio flooded to a depth of five feet, destroying expensive equipment — and most of his life’s work of prints from glass plate negatives.

Pennsylvania oil towns were “Nearly Wiped From Off the Earth” by an 1892 fire and flood that destroyed thousands of Mather’s prints and glass plates. Photo from Drake Well Museum collection.

As the fires and flood continued, Mather set up his camera and photographed the disaster in progress with his bulky equipment, which already was being rendered obsolete by new imaging technologies.

Photography Legacy

Just a few years before the Titusville flood, George Eastman of Rochester, New York, introduced celluloid roll film and created an entirely new market: amateur snapshot photography.

Expertise in preparing fragile glass plates and dangerous chemicals was no longer required. Instead, Kodak offered, “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest.”

The “Oil Creek Artist” visited potential customers using his floating darkroom.

As oil booms moved to discoveries in other states, including the massive 1901 “Lucas Gusher” in Texas, Mather worked little in his later years. His financial circumstances diminished with age and illness.

The Artist of Oil Creek died poor and without fanfare on August 23, 1915, in Titusville. His death certificate reported the cause as cerebral hemorrhage, “complicated by suppression of urine.”

An 1865 John Mather photograph of wooden derricks, engine houses, oilfield workers, an office (and tree stumps) at Pioneer Run – Oil Creek, Pennsylvania.

To preserve John A. Mather’s petroleum industry legacy, the Drake Well Memorial Association purchased 3,274 surviving glass negatives for about 30 cents each.

The Drake Well Museum has preserved the photographer’s surviving work. The museum and surrounding park allow visitors to explore rare artifacts and a visual record of the early U.S. oil and natural industry. Visit the Titusville museum along Oil Creek and other Pennsylvania petroleum museums.

More Resources

“Virtually unknown, certainly unheralded, and completely unappreciated — in these few words is a description of John Aked Mather, pioneer photographer, ” proclaimed Ernest C. Miller and T.K. Stratton in their January 1972 article, “Oildon’s Photographic Historian,” in The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine (Volume 55, Number 1).

Born in Heapford Bury, England, in 1829, the son of an English papermill superintendent, Mather joined his two brothers in America in 1856. He soon became “transfixed by the beauty of the Pennsylvania and Eastern Ohio regions,” explains a NWPaHeritage article, adding he developed an “obsessive desire to capture the industry in its entirety.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); Around Titusville, Pa., Images of America

(2008); Around Titusville, Pa., Images of America (2004); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2004); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oilfield Photographer John Mather.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/oilfield-photographer-john-mather. Last Updated: May 30, 2025. Original Published Date: March 11, 2005.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 29, 2025 | Petroleum Art

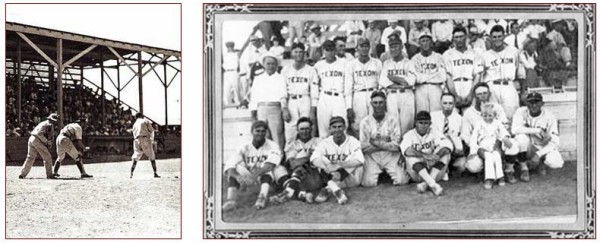

The first pitcher ever inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, Walter “The Big Train” Johnson, worked in California oilfields as a teenager; his famed career began with a company town baseball team. Players sometimes made it to the Big Leagues — and the Baseball Hall of Fame.

As baseball became America’s favorite pastime in the early 20th century, booming oil towns fielded winning teams with names that reflected their communities’ enthusiasm and often their livelihood.

In Texas, the booming petroleum town of Corsicana fielded the Oil Citys — and made baseball history in 1902 with a 51 to 3 drubbing of the Texarkana Casketmakers. Oil Citys catcher Jay Justin Clarke hit eight home runs in eight at bats during the game, still an unbroken baseball record.

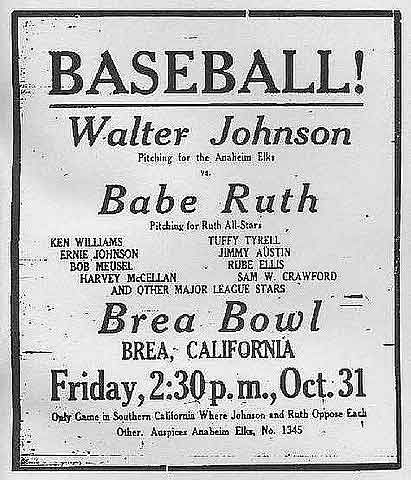

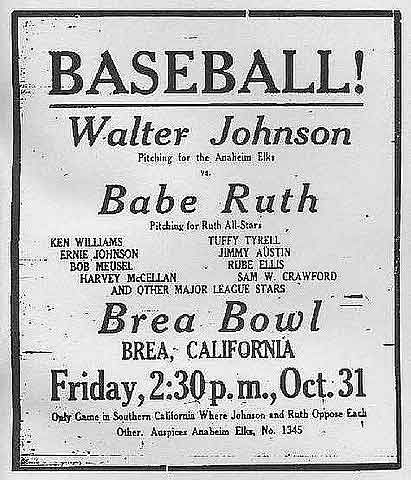

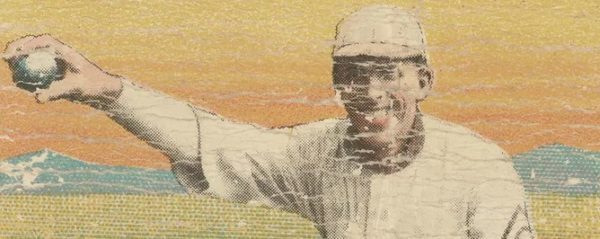

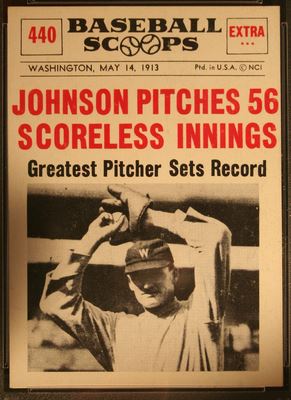

Former pitcher for the Olinda Oil Wells — Walter “The Big Train” Johnson — joined “Babe” Ruth in a 1924 exhibition game. Johnson was among the first players inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1922, the Wichita Falls minor league team lost its opportunity for a 25th consecutive victory when the league determined the team had “doctored the baseball.” The Wichita Falls ballpark caught fire in June — during a game — and burned to the ground. It was a memorable season.

The Double-A team Tulsa Drillers began in 1977 when the Lafayette Drillers moved to Tulsa.

In Oklahoma oilfields, the Okmulgee Drillers for the first time in baseball history had two players who combined to hit 100 home runs in a single season of 160 games. First baseman Wilbur “Country” Davis and center fielder Cecil “Stormy” Davis accomplished their home run record in 1924, although their team faded away by 1927.

With a growing population thanks to giant oilfields discoveries at nearby Red Fork (1901) and Glenn Pool (1905), the Tulsa Oilers dominated the Western League for a decade, winning the pennant in 1920, 1922, and 1927-1929. The name has continued in the hockey league’s Tulsa Oilers.

In 1977, the double-A affiliate team for the Major League Baseball, the Tulsa Drillers, arrived in the city from Lafayette, Louisiana.

First Night Game

For baseball’s first official night game on April 28, 1930, a company town baseball team — the Producers of Independence, Kansas, lost to the Muskogee Chiefs 13 to 3. The game played under portable lights supplied by the Negro National League’s Kansas City Monarchs.

The Olinda No. 1 well of 1898 created an oil boom town. Hundreds of wells once pumped oil around the Olinda Oil Museum and Trail near Brea, California.

The Independence Producers were one of the 96 teams in the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, later known as Minor League Baseball.

Iola Gasbags and Borger Gassers

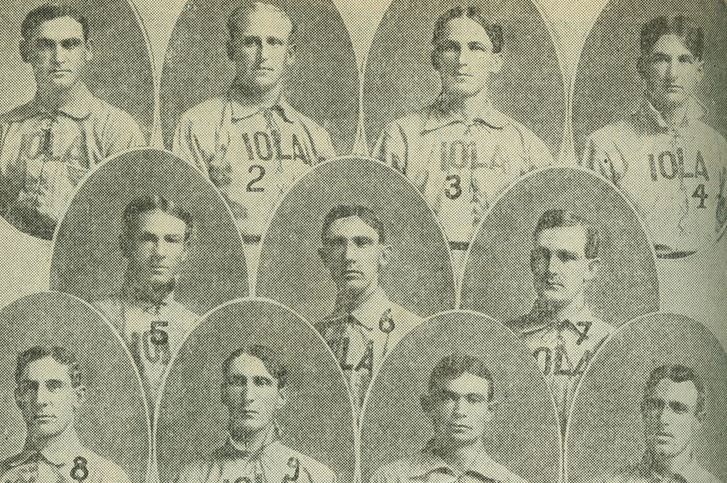

Thanks to mid-continent oil and natural gas discoveries, in just nine years beginning in 1895, Iola, Kansas, grew from a town of 1,567 to a city of more than 11,000. Gas wells lighted the way.

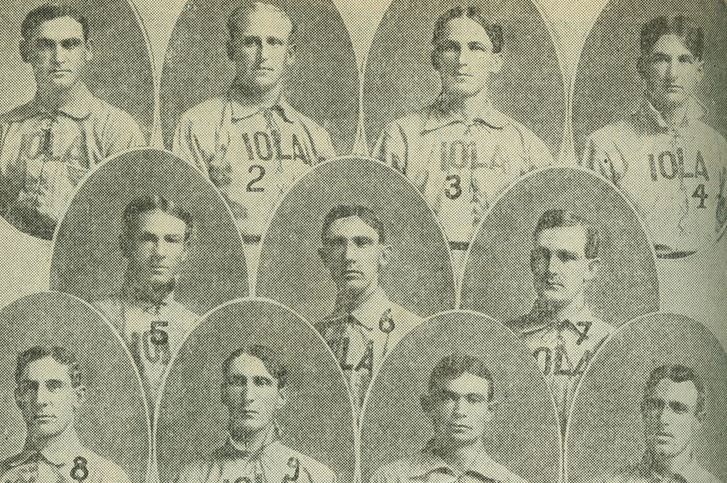

However, the Iola Gasbags reportedly adopted their team name not for the resource, but after becoming known as braggers in the Missouri State League. “They traveled to these other cities, and they’d be bragging that they were the champions, so people started giving them the nickname Gasbags,” reported baseball historian Tim Hagerty in a July 2012 National Public Radio interview.

A natural gas boom in Kansas led to a baseball team being named the Iola Gasbags, pictured here in 1904. Photo courtesy National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

In 1903, the players renamed themselves the Iola Gaslighters — but had a change of heart and reverted to the original name the following season.

“They said, ‘You know what? Yeah, we are, We’re the Gasbags.'” added Hagerty, author of Root for the Home Team: Minor League Baseball’s Most Off-the-Wall Names and the Stories Behind Them. “I think the state of Kansas may take the prize for the most terrific names — the Wichita Wingnuts, the Wichita Izzies, the Hutchinson Salt Packers…and the Iola Gasbags.”

In the Texas Panhandle, the petroleum-related town baseball team Borger Gassers disappeared after the 1955 season, despite Gordon Nell hitting a record-setting 49 homers in 1947. Team owners blamed television and air-conditioning for reducing minor league baseball attendance and profitability.

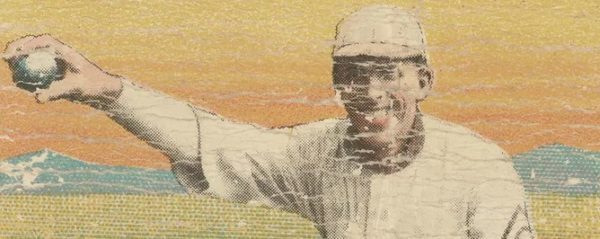

Detail from 1909 baseball card featuring Pacific Coast League pitcher Jimmy Wiggs. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

In Beaumont, Texas, site of the great Spindletop oil discovery of 1901, minor league baseball lasted for decades under several names. The first team, the Beaumont Oil Gushers of the South Texas League, was fielded in 1903. By the 1904 season the team was known as the Millionaires and then the Oilers before becoming the Beaumont Exporters in 1920.

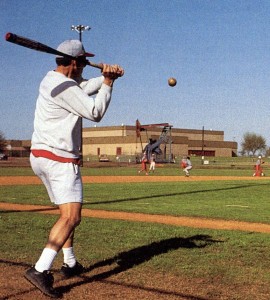

East of Dallas, in Van, Texas, fielding practice at the oil town baseball high school includes a reminder of a prolific oilfield discovered in 1929. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Although many thought the name should be changed to the Refiners, reflecting the city’s industry, for the 1950 season the team was briefly known as the Roughnecks (a former company town baseball team name still popular).

Beaumont’s last AA Texas League team was the Golden Gators, which folded in 1986. Another team in the Texas League, the company town baseball team Shreveport Gassers, on May 8, 1918, played 20 innings against the Fort Worth Panthers before the game was finally declared a tie at one to one.

Pitching for the Olinda Oil Wells

Perhaps baseball’s greatest product from the oilfield was a young man who was a roustabout in the small oil town of Olinda, California. Walter Johnson (1887-1946) would earn national renown as the greatest pitcher of his time. His fastball was legendary.

In 1894, the Union Oil Company of Santa Paula purchased 1,200 acres in northern Orange County for oil development. Four years later the first oil well, Olinda No. 1, came in and created the oil boom town. Soon, the Olinda baseball players began making a name for themselves among the semi-pro teams of the Los Angeles area.

A 1961 baseball card notes headline of the former California oilfield roustabout’s amazing 1913 pitching record, which lasted until Don Drysdale pitched 58 scoreless innings in 1968.

By 1903, the Orange County team was sharing newly built Athletic Park in Anaheim, “two hours south of Olinda by horse and buggy,” noted one historian. Youngster Walter Johnson rooted for the local team, the Oil Wells.

Johnson, originally from Humboldt, Kansas, moved to the thriving oil town east of Brea with his family when he was 14. He attended Fullerton Union High School and played baseball there while working in the nearby oilfields. His high school pitching began making headlines, including a 15-inning game against rival Santa Ana High School in 1905 where he struck out 27.

Today, tourists visit the Olinda Oil Museum and Trail. This historic Orange County site includes Olinda Oil Well No. 1 of 1898, the oil company field office and a jack-line pump building.

By 17, Johnson was playing for his oil town baseball team, the Olinda Oil Wells, as its ace pitcher. He shared in each game’s income of $25, according to Henry Thomas in Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train.

“Not a bad split for nine players considering that a roustabout in the oilfields started at $1.50 a day,” Thomas noted in his book. Johnson finished with a winning season and soon moved on to the minor leagues.

Johnson’s major league career began in 1907 in Washington, D.C., where he played his entire 21-year baseball career for the Washington Senators. The former oil patch roustabout in 2022 remained major league baseball’s all-time career leader in shutouts with 110, second in wins (417) and fourth in complete games (531).

In 1936, “The Big Train” Johnson was inducted into baseball’s newly created Hall of Fame with four others: Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, and Christy Mathewson. In 1924, Johnson returned to his California oil patch roots. On October 31, he and his former baseball teammates played an exhibition game in Brea against Babe Ruth and the Ruth All-Stars.

The Brea Museum & Historical Society today includes exhibits, rare photographs, and research facilities. There’s also an on-going project recreating Brea in miniature.

Texon Oilers of the Permian Basin

On May 28, 1923, a loud roar was heard when the Santa Rita No. 1 well erupted in West Texas. People as far away as Fort Worth traveled to see the well.

Near Big Lake, Texas, on arid land leased from the University of Texas, Texon Oil and Land Company made the discovery (the school would earn millions of dollars in royalties). The giant oilfield, about 4.5 square miles, revealed the extent of oil reserves in West Texas. Exploration spread in the Permian Basin, still one of the largest U.S. oil-producing regions.

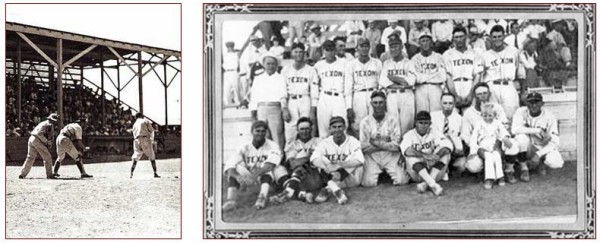

The first oil “company town” in the Permian Basin, Texon, was founded in 1924 by Big Lake Oil Company. The Texon Oilers won Permian Basin League championships in 1933, 1934, 1935 and 1939. Texon remains a tourist attraction – as a ghost town.

Early Permian Basin discoveries created many boom towns, including Midland, which some would soon refer to as “Little Dallas.”

By 1924, Michael L. Benedum, a successful independent oilman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and other successful independent producers — wildcatters — formed the Big Lake Oil Company. The new company established Texon, the first oil company town in the Permian Basin. Texon residents fielded a company town baseball team.

Today a ghost town, Texon was considered a model oil community. It had a school, church, hospital, theater, golf course, swimming pool – and a semi-pro company baseball team.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, the Texon Oilers baseball team was the centerpiece of the employee recreation plan of Levi Smith, vice president and general manager of the Big Lake Oil Company. Smith organized the club after he founded the Reagan County town west of Big Lake.

The Permian Basin oilfield was featured in a 2002 movie featuring a high school teacher and baseball coach. Image from Walt Disney Pictures poster.

By the summer of 1925 a baseball field was ready for use. In 1926 a 500-seat grandstand completed the facility. “In 1929 the Big Lake Oil Company began a tradition of hosting a Labor Day barbecue for employees and friends, highlighted by a baseball game,” noted historian Jane Spraggins Wilson.

“Management consistently attempted to schedule well-known clubs, such as the Fort Worth Cats and the Halliburton Oilers of Oklahoma,” added Wilson, who explained that during the Great Depression, “before good highways, television, and other diversions, the team was a source of community cohesiveness, entertainment, and pride.”

After the World War II, with its famous the oilfield diminishing and the town losing population, aging Oilers left the game for good, Wilson reports. By the mid-1950s the Texon Oilers company town baseball team were but a memory.

Hollywood visits Oilfields

The 2002 movie “The Rookie” — filmed almost entirely in the Permian Basin of West Texas — featured a Reagan County High School teacher. Based on the “true life” of baseball pitcher Jimmy Morris, it tells the story of baseball coach, Morris (played by Dennis Quaid), who despite being in his mid-30s briefly makes it to the major leagues.

The movie, promoted with the phrase, “It’s never too late to believe in your dreams,” begins with a flashback scene near Big Lake, the Santa Rita No. 1 drilling site.

At the beginning of the 2002 movie “The Rookie,” Catholic nuns christened the Santa Rita No. 1 cable-tool rig. In reality, one of the well’s owners climbed the derrick and threw rose petals given to him by Catholic women investors.

As the well is being drilled, Catholic nuns are shown carrying a basket of rose petals to christen it for the patron Saint of the Impossible – Santa Rita. “Much is made of the almost mythic importance of oil in Big Lake, with talk of the Santa Rita oil well,” explained ESPN in The Rookie in Reel Life.

Learn more about the Permian Basin by visiting the Petroleum Museum in Midland.

Company Town Baseball: Oilmen of Whiting, Indiana

In 1889, the Standard Oil Company began construction on its massive, 235-acre refinery in Whiting, Indiana. Today owned by BP, the Whiting refinery is the largest in the United States.

Whiting has been home to the Northwest Indiana Oilmen since 2012.

In 2012, Whiting fielded a baseball team. On June 3, the Northwest Indiana Oilmen crushed the Southland Vikings 14-3 at Oil City Stadium in Standard Diamonds Park for the first win in franchise history. The Oilmen team became one of eight in the Midwest Collegiate League, a pre-minor baseball league.

Standard Oil’s giant refinery in Whiting, Indiana, processed “sour crude” in the early 1900s. Now owned by BP, it is the largest U.S. refinery. The city of Whiting incorporated in 1903.

“The name Oil City Stadium celebrates Whiting’s history as a refinery town tucked away in the Northwest corner of Indiana for over 120 years,” noted team owner Don Popravak about the oil company town baseball. “The BP Refinery, located just beyond the outfield fence is a constant reminder of the blue-collar attitude Whiting was built on,” he added.

CITGO and Oil History

With the arrival of baseball’s opening day in 2024, David Krell published a book about the Boston Red Sox and the role of the former Cities Service Company — CITGO — red triangle sign at Fenway Park. While researching The Fenway Effect: A Cultural History of the Boston Red Sox, Krell discovered the extensive history behind the company and its sign at Fenway, the team’s home ballpark since 1912.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill Teams, 1880-1955 (2004); The Fenway Effect: A Cultural History of the Boston Red Sox (2024). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2004); The Fenway Effect: A Cultural History of the Boston Red Sox (2024). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oilfields of Dreams – Gassers, Oilers, and Drillers Baseball.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/oil-town-baseball. Last Updated: April 29, 2025. Original Published Date: September 1, 2007.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 8, 2025 | Petroleum Art

Pennsylvania oilfield tragedy led to new safety and firefighting technologies — and a work of art.

The danger involved in America’s early petroleum industry was revealed when the first commercial well went up in flames just weeks after finding oil in the summer of 1859 — becoming the first oil well fire. More serious infernos would follow as the young industry’s early technologies struggled to keep up.

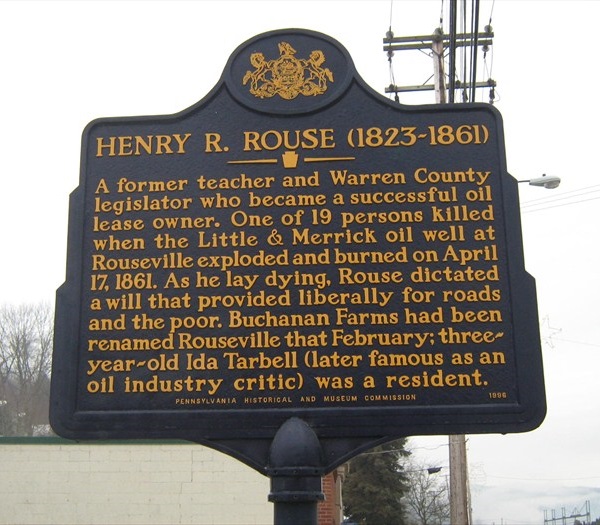

While the Pennsylvania oil region grew — and wooden derricks multiplied on hillsides — an 1861 deadly explosion and fire at Rouseville added urgency to the industry’s need for inventing safer ways for drilling wells.

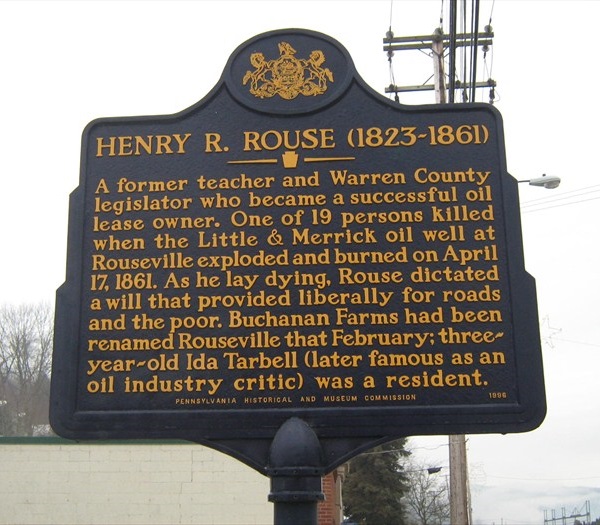

A marker was dedicated in 1996 on State Highway 8 near Rouseville by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Henry Rouse’s reputation made him a respected leader in the early oil industry.

On April 17, 1861, a highly pressurized well’s geyser of oil exploded in flames on the Buchanan Farm at Rouseville, killing the well’s owner and more than a dozen bystanders.

Sometimes called “Oil Well Fire Near Titusville” but more accurately, Rouseville, the early oilfield tragedy was overshadowed by the greater tragedy of the Civil War. Fort Sumter fell on April 13, 1861; Henry Rouse’s oil well exploded four days later.

The Little and Merrick well at Oil Creek, drilled by respected teacher and businessman Henry Rouse, unexpectedly had hit a pressurized oil and natural gas geologic formation at a depth of just 320 feet. Given the limited drilling technologies for controlling the pressure, the well’s production of 3,000 barrels of oil per day was out of control.

The Rouse Estate later reported, “A breathless worker ran up to him, telling him to ‘come quickly’ as they’d ‘hit a big one.’ According to the best accounts of the time, the ‘big one’ was the world’s first legitimate oil gusher. As oil spouted from the ground, Henry Rouse and the others stood by wondering how to control the phenomenon.”

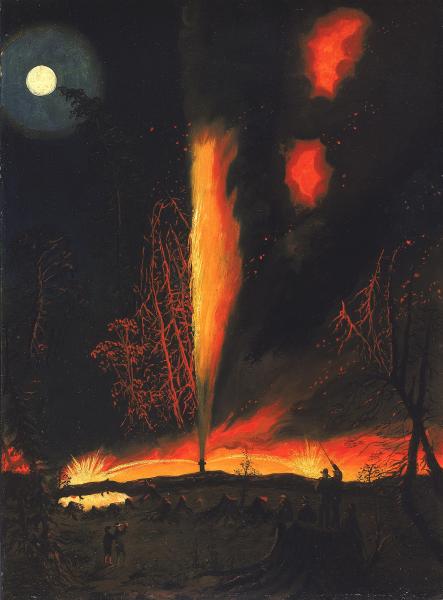

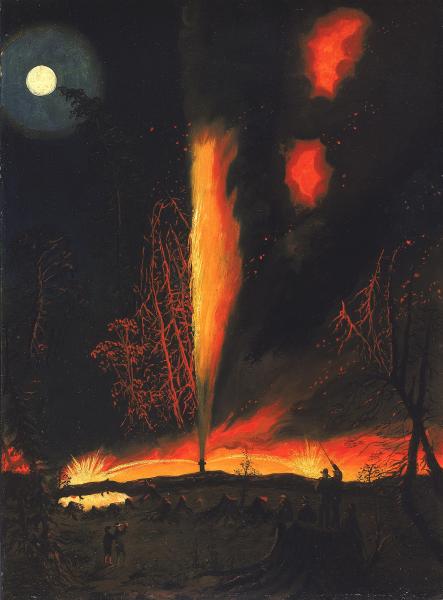

Detail from “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” a painting by James Hamilton of the 1861 oil well fire that killed Henry Rouse today is in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

The towering gusher also had attracted people from town; many had become covered with oil. Perhaps ignited by the steam engine’s boiler, the well suddenly erupted into flames that engulfed Rouse, killing him and 18 others and seriously burning many more.

Historian Michael H. Scruggs of Pennsylvania State University found a dramatic account from an eyewitness, who reported:

“One of the victims it would seem had been standing on these barrels near the well when the explosion occurred; for I first discovered him running over them away from the well. He had hardly reached the outer edge of the field of fire when coming to a vacant space in the tier of barrels from which two or three had been taken, he fell into the vacancy, and there uttering heart-rending shrieks, burned to death with scarcely a dozen feet of impassable heated air between him and his friends.”

Henry R. Rouse, 1823-1861.

Scruggs noted the 37-year-old Henry Rouse was dragged from the fire severely burned, and expecting the worst, dictated his Last Will and Testament, “to the men surrounding him as they fed him water spoonful by spoonful.”

Engraved on an 1865 marble monument (re-dedicated to Rouse’s memory during a family reunion in 1993) is this tribute:

Henry R. Rouse was the typical poor boy who grew rich through his own efforts and a little luck. He was in the oil business less than 19 months; he made his fortune from it and lost his life because of it. He died bravely, left his wealth wisely, and today is hardly remembered by posterity. — from the Rouse Estate.

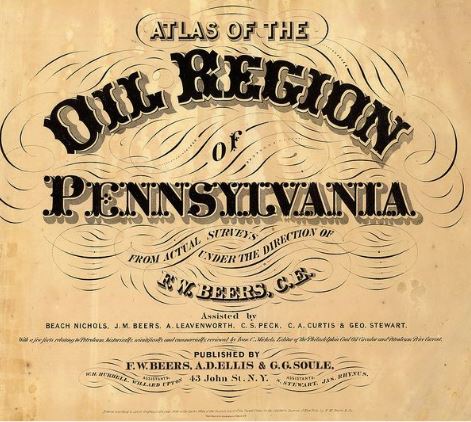

The 1865 Atlas of the Oil Regions of Pennsylvania by Frederick W. Beers described this early petroleum industry tragedy in detail:

It was upon this farm (Buchanan) that the terrible calamity of April 1861, occurred, when several persons lost their lives by the burning of a well. The “BURNING WELL” as it has since been called, had been put down to the depth of three hundred and thirty feet, when a strong vein of gas and oil was struck, causing suspension of operations and ejecting a stream from the well as high as the top of the derrick.

“Atlas of the Oil Regions of Pennsylvania,” published by Frederick W. Beers in 1865.

Large numbers of persons were attracted to the scene, when the gas filling the atmosphere took fire, as is supposed, from a lighted cigar, and a terrible explosion ensued, which was heard for three or four miles. The well continued to burn for upwards of twenty hours destroying the tanks and machinery of several adjacent wells, and several hundred barrels of oil. The scene is represented as terrific beyond comparison.

The well spouted furiously for many hours, and the column of flame extended often two and three hundred feet in height, the valley being shut in, as it were, by a dense and impenetrable canopy of overhanging smoke. Fifteen persons were instantly killed by the explosion of the gas, and thirteen others scarred for life.

Among the persons killed was Mr. Henry R. Rouse, who had then recently become interested in that locality, and after whom Rouseville takes its name. The well continued to flow at the rate of about one thousand barrels per day for a week after the fire, when it suddenly ceased, and has since produced very little oil as a pumping well.

These fires have not been unfrequent, and it is a little remarkable that in every case where wells have been so burned they have never after produced save in very small quantities.

Late 1860s stereograph by William J. Portser showing men and women standing on a storage tank and two men at the top of an oil derrick in Pennsylvania, courtesy Library of Congress.

According to historian Scruggs, the knowledge gained from the 1861 disaster along with other early oilfield accidents brought better exploration and production technologies. The first “Christmas Tree” — an assembly of control valves – was invented by Al Hamills after the 1901 gusher at Spindletop Hill, Texas.

Although the deadly Rouseville well fire caused tragedy and devastation, “the knowledge gained from the well along with other accidents helped pave the way for new and safer ways to drill,” Scruggs wrote in his 2010 article.

“These inventions and precautions have become very important and helpful, especially considering many Pennsylvanians are back on the rigs again, this time drilling for the Marcellus Shale natural gas,” he concluded.

Learn more about another important invention, Harry Cameron’s 1922 blowout preventer in Ending Gushers – BOP.

Oil Well Fire at Night

The tragic Pennsylvania oil well fire was immortalized by Philadelphia artist James Hamilton, a mid-19th century painter whose landscape and maritime works are in collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Tate Gallery in London, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, D.C.

Acquired by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2017, artist James Hamilton’s “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” was on display in 2018. Photo by Bruce Wells.

In 2017, the Smithsonian museum acquired Hamilton’s “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” circa 1861 (oil on paperboard, 22 inches by 16 1⁄8 inches, currently not on view).

“Rouseville, Pennsylvania, lay within a few miles of Titusville and Pithole City, two of the most famous boom towns in Pennsylvania ’s oil fields,” noted the museum’s 2017 description of the painting.

“From 1859 until after the Civil War, new gushers brought investors, cardsharps, saloons, and speculators into these rural settlements. As quickly as they grew, however, the towns collapsed, often from the effects of fires like the one shown here,” noted the Smithsonian’s description.

Flames shooting from the wellhead are part of the circa 1861 “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” by James Hamilton.

“In the 1860s, American industrialist John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) was in the thick of this oil boom, maneuvering to establish the Standard Oil Company,” the museum’s painting description added. “Rockefeller’s investments in railroads and refineries would make him one of America’s richest men, long after the wildcatters in the Pennsylvania fields had gone bust.”

Famed journalist and Rockefeller antagonist Ida Tarbell lived in Rouseville as a child.

Following the Civil War, with consumers increasingly demanding kerosene for lamps (and soon gasoline for autos), the search for oilfields moved westward. The young petroleum industry also developed safety and accident prevention methods alongside new oilfield firefighting technologies.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Atlas of the oil region of Pennsylvania (1984); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania (2000); Warren County (2015). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “Fatal Oil Well Fire of 1861.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/first-oil-well-fire. Last Updated: April 12, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.