by Bruce Wells | Jan 10, 2025 | Petroleum Art

Dr. Seuss created zoological oddities for Esso products of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey.

Seuss the oilman? Thirty years before the Grinch stole Christmas in 1957, many strange and wonderful critters of the popular children’s book author could be seen in Standard Oil Company advertising campaigns.

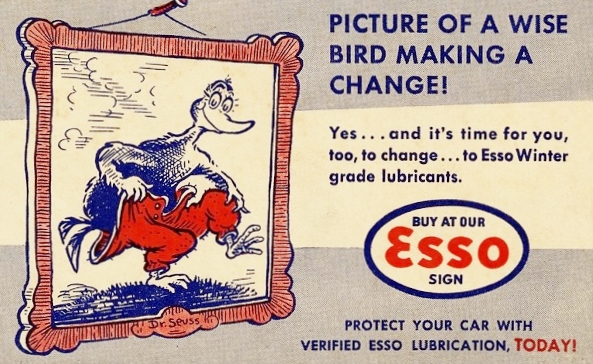

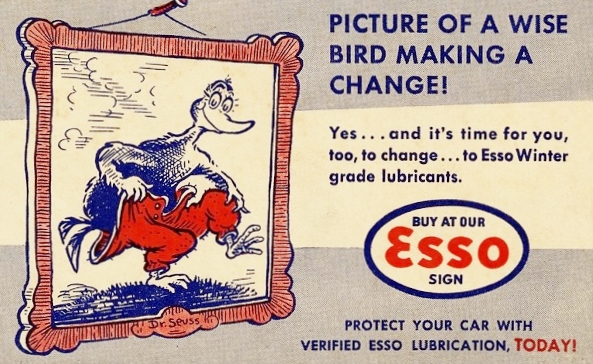

Between 1930 and 1940, Theodor Seuss Geisel created distinctive characters for Standard Oil advertising campaigns, including this “wise bird” for Essolube oil change cards. Illustration courtesy University of California San Diego Library.

During the Great Depression, fanciful creatures drawn by the future Dr. Seuss promoted Essolube and other products for Standard Oil of New Jersey. He later said his experience at Standard, “taught me conciseness and how to marry pictures with words.”

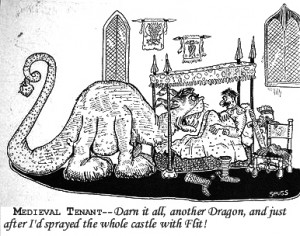

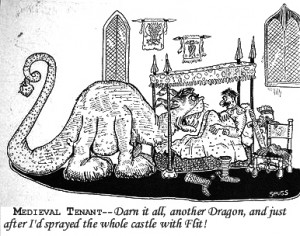

A 1927 cartoon by Theodor Seuss Geisel featured Standard Oil’s petroleum product “Flit,” a popular bug spray.

In the cartoon that launched his career, Theodor Seuss Geisel drew a peculiar dragon inside a castle. The January 14, 1928, issue of New York City’s Judge magazine featured the scaled beast. Geisel would introduce many less threatening characters inhabiting his imaginative menagerie.

Bug Spray

“Flit,” was a popular bug spray of the day — especially against flies and mosquitoes. It was one of many Standard Oil Company of New Jersey consumer products derived from oil and natural gas (also see petroleum products).

Late in 1927, Standard Oil’s growing advertising department, which had focused on sales of Standard and Esso gasoline, lubricating oil, fuel oil and asphalt, reorganized to promote other products, according to author Alfred Chandler Jr.

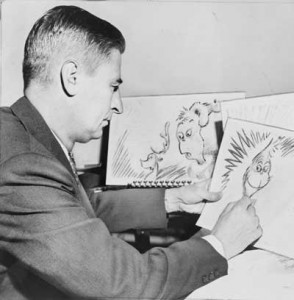

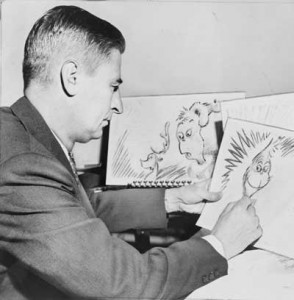

Dr. Seuss later said his experience working at Standard Oil helped him develop his fantastical characters and tales.

“Specialties, such as Nujol, Flit, Mistol, and other petroleum by-products that could not be effectively sold through the department’s sales organization were combined in a separate subsidiary — Stanco,” noted Chandler in his book, Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise.

Chandler’s 1962 book also examined General Motors Company, Sears, Roebuck and Company, and gunpowder manufacturer E.I. du Pont de Nemours.

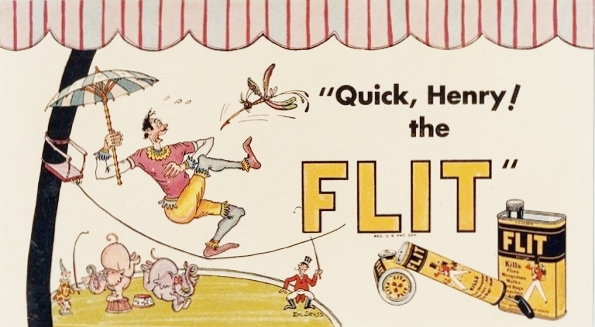

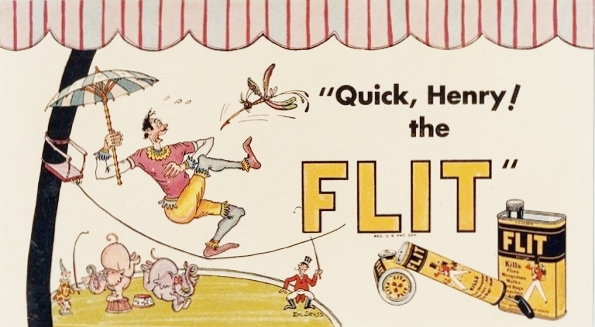

“Quick, Henry, the Flit!”

Geisel’s fortuitous bug-spray cartoon depicted a medieval knight in his bed, facing a dragon who had invaded his room, and lamenting, “Darn it all, another dragon. And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit.”

According to an anecdote in Judith and Neil Morgan’s 1995 book Dr. Seuss and Mrs. Geisel, the wife of the advertising executive who handled the Standard Oil account was impressed by the cartoon.

Circa 1935 ad for a Standard Oil petroleum product was characteristic of the imagination that would make Ted Geisel the definitive children’s book author. Illustration courtesy University of California San Diego Library.

“At her urging, her husband hired the artist, thereby inaugurating a 17-year campaign of ads whose recurring plea, ‘Quick, Henry, the Flit!,’ became a common catchphrase,” noted a curator of the Dr. Seuss Collection at the University of California, San Diego.

“These ads, along with those for several other companies, supported the Geisels throughout the Great Depression and the nascent period of his writing career,” the curator added.

Besides promoting the Standard Oil companies Flit and Esso, Dr. Seuss’ creations helped sell such diverse goods as ball bearings, radio programs, beer brands, and sugar, notes the library, located in La Jolla, where Geisel was a longtime resident.

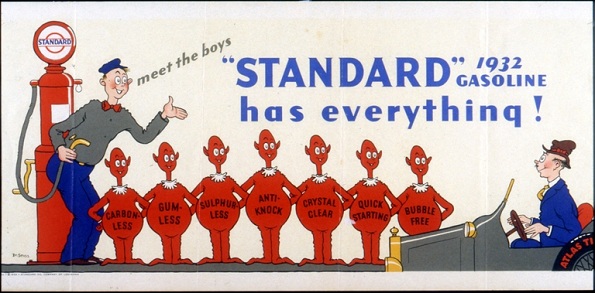

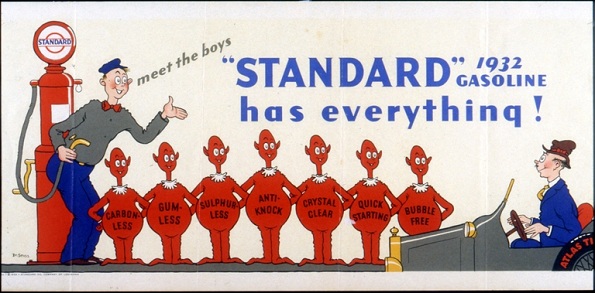

This 1932 Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) advertisement is among those preserved by the Dr. Seuss Collection of the Mandeville Special Collections Library at the University of California, San Diego.

At the University of California, San Diego, the Dr. Seuss Collection in the Mandeville Special Collections Library contains original drawings, sketches, proofs, notebooks, manuscript drafts, books, audio and videotapes, photographs, and memorabilia.

More than 8,500 items document and preserve Dr. Seuss’ creative achievements, beginning in 1919 with his high school activities and ending with his death in 1991.

Karbo-nockus and Other Critters

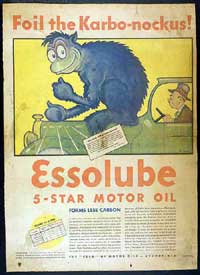

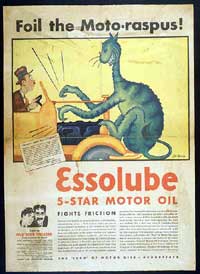

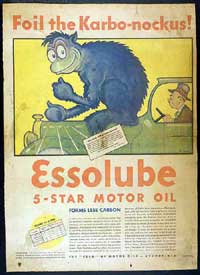

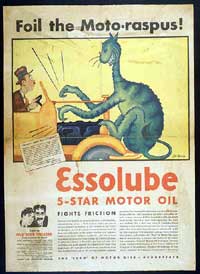

The future Dr. Seuss added a host of zoological oddities to Standard Oil’s lexicon while promoting the product of Esso (the phonetic pronunciation of the initials S and O first used in 1926). His critters promoted Essomarine oil and greases as well as Essolube Five-Star Motor Oil.

Standard Oil advertising campaigns provided a steady income to Geisel and his wife throughout his early days experimenting with his drawings.

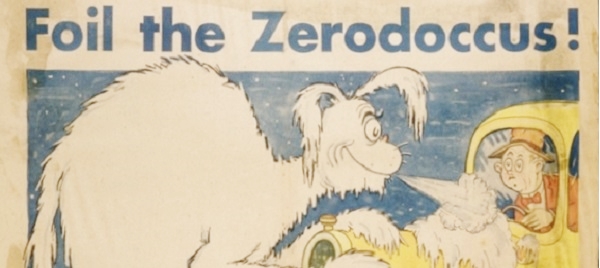

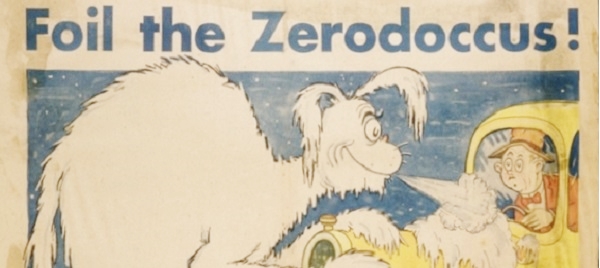

Smiling, toothy creatures such as Zero-doccus, Karbo-nockus, Moto-raspus and Oilio-Gobelus appeared in advertisements that warned motorists of the hazards of driving without the protection of Standard Oil lubrication.

Motor oil cartoon ad drawn by the future children’s book author Dr. Seuss. First sold in the 1930s, Essolube has remained a popular product, today for ExxonMobil.

“Meet the Zero-doccus. He is the first if a group of terrible beasts that are being turned loose in the advertising of Essolube, Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) products,” reported the December 8, 1932, Printers’ Insider, an advertising trade journal.

Other Esso “moto-monsters” would be introduced in newspapers and outdoor posters in coming months, the trade journal proclaimed.

“These creatures symbolize and dramatize some of the troubles of motorists who use inferior oils. The Zero-doccus pounces on cold motors and makes quick starting difficult with ordinary oils,” the article noted. “He and his coming friends are the creations of Dr. Seuss of ‘Quick, Henry, the Flit’ fame.”

The Printers’ Insider article predicted the strange Esso creatures would prove popular when they appeared in ads nationwide.

A dependable income from Standard Oil during the Great Depression helped Dr. Seuss publish his first children’s book in 1936.

Seuss in Esso Navy

Throughout his early hard years, these Standard Oil advertising campaigns provided steady income to Geisel and his wife. “It wasn’t the greatest pay, but it covered my overhead so I could experiment with my drawings,” he later said.

Geisel noted his advertising work allowed him to experiment with creating subtle visual messages while using wacky rhymes in storytelling.

In 1936, Geisel designed Standard Oil’s Essomarine booth for the National Motorboat Show — and created the phenomenally successful “Seuss Navy.” Young and old visitors were commissioned as admirals and photographed with whimsical characters made of cardboard.

Standard Oil Company marketers promoted Essomarine products during the 1940 National Motor Boat Show in New York City.

By 1940, the Seuss Navy included more than 2,000 enthusiastic admirals (with such notables as bandleader Guy Lombardo). Geisel remembered that, “It was cheaper to give a party for a few thousand people, furnishing all the booze, than it was to advertise in full-page ads.”

As Dr. Seuss, Geisel wrote and illustrated his first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, published on December 21, 1937, by Vanguard Press after being rejected by 27 other publishers.

Twenty years later, The Cat in the Hat was inspired by a 1954 Life Magazine essay critical of children’s literacy and the stilted “See Spot Run” style of reading primers. Published in 1957, The Cat in the Hat used just 236 words — and only 14 of them with two syllables. It remains his most popular work.

The former Standard Oil advertising illustrator wrote more than 50 children’s books over a half-century career that brought the world Hop on Pop, Green Eggs and Ham and many others. Children lost a friend on September 24, 1991, when Theodor Seuss Geisel died at the age of 87.

View online the Dr. Seuss Collection: Advertising Artwork of Dr. Seuss, preserved by Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California.

Kerosene in Art

At the beginning of the 20th century, French illustrator Jules Chéret (1836-1933) was famous for his lithograph posters for theatres, music halls, beverages, and medicines. During a long career, many of his commercial posters promoted a French petroleum company’s lamp oil.

Chéret, who would be called “the father of the modern lithograph” and “king of the poster,” produced popular posters for “Saxoleinem,” the company’s refined “pétole de sureté”– safety lamp oil.

French advertisement for “The Halo of the South,” a safety oil for lamps, in an 1895-1900 lithograph by artist Jules Chéret.

“He was often imitated, and an entire generation of artists would follow and build on his work. One of them was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec,” notes Chicago’s Richard H. Driehaus Museum. “To acknowledge his debt to the older artist, Lautrec sent Chéret a copy of every poster he produced.”

Learn about more examples of artists and the petroleum industry in Oil in Art.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Theodor Geisel: A Portrait of the Man Who Became Dr. Seuss (2010); The History of the Standard Oil Company: All Volumes

(2010); The History of the Standard Oil Company: All Volumes  (2015); Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise (1962); Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography (1995). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2015); Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise (1962); Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography (1995). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Seuss I am, an Oilman.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/seuss-the-oilman. Last Updated: January 9, 2025. Original Published Date: December 1, 2008.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 16, 2024 | Petroleum Art

Advertising character became a petroleum industry award — and monuments in Texas parks.

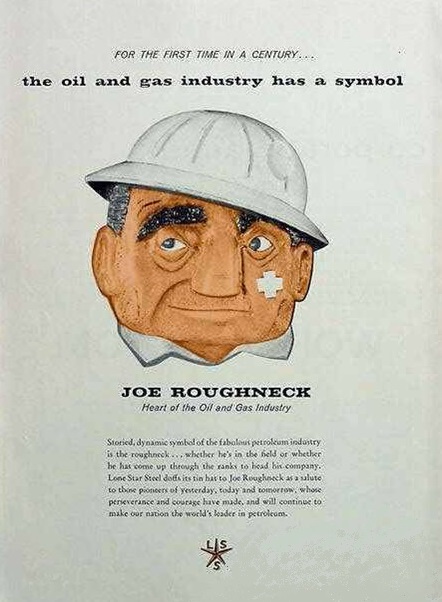

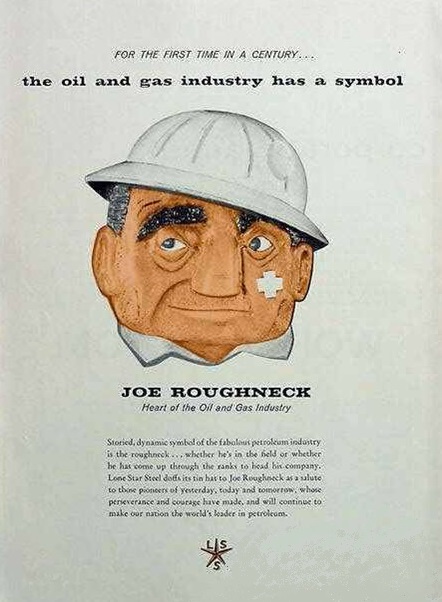

Joe Roughneck’s rugged, square-jawed face first appeared in the 1950s as print advertisements for a tubular goods manufacturer. His helmeted visage in bronze became a petroleum industry award annually handed out to wildcatters “whose accomplishments and character represent the highest ideals of the oil and natural gas industry.”

Presented from 1955 to 2019 during conventions of a national oil and gas industry trade association, Joe’s Chief Roughneck statue symbolized the “leadership and integrity of individuals who have made a lasting impression on the energy industry.”

Torg Thompson, who in the 1950s drew the original for ads, sculpted the oilfield character “Joe Roughneck” for an annual industry award and display in Texas public parks.

The award’s bronze bust began with Texas artist Torg Thompson (1905-1998) and the Lone Star Steel Company, later U.S. Steel Tubular Products, a subsidiary of United States Steel. Thompson’s busts, sculpted from a character in newspaper and magazine ads, also would be dedicated in Texas parks.

Recipients of the pipe manufacturer’s “Chief Roughneck Award” — first presented to independent producer R.E. (Bob) Smith in 1955 — included Harold Hamm, George Mitchell, Dean McGee, H.L Hunt, and W.A. “Monty” Moncrief.

The advertising character’s battered face became popular in America’s oilfields, prompting Lone Star Steel executives to proclaim, “Joe doesn’t belong to us anymore. He’s as universal as a rotary rig.”

The advertising character began his career on the scratch pad of Thompson, also known for the 124-by-20-foot mural, “Miracle at Pentecost,” at the Biblical Arts Center in Dallas (destroyed by fire in 2005). For Lone Star Steel Company ads, Thompson portrayed Joe with the rugged countenance of a man who had spent long hours working in oilfields.

In 1959, Lone Star Steel Company, an oil field tubular goods manufacturer, produced this magazine advertisement featuring Joe Roughneck, the “Heart of the Oil and Gas Industry.”

“Joe’s jaw was squarely set to denote determination, his nose flattened as a souvenir of the rollicking life of a boom town. His eyes indicate the kindness and generosity of his breed. His mouth wore the trace of a smile, but there was a quizzical expression of one who had to see to believe,” notes a small museum in the heart of the East Texas oilfield.

“When the completed picture came into being on canvas, there was no doubt Joe was the heart of the oil patch,” the Depot Museum in Henderson adds.

Joe has been saluted by two Governors of Texas, named “Man of the Month” by a popular magazine, and has been the subject of countless newspaper articles, along with many radio and television commentaries. Joe also became the mascot of the White Oak Roughnecks, a high school football team of another East Texas oilfield community.

“Joe’s likeness has adorned the world’s largest golf trophy and once decorated an international oil exposition,” the Depot Museum concludes.

At the Gaston Museum in Joinerville, Texas, a Joe Roughneck memorial was dedicated “to the pioneers of the Great East Texas oilfield.” The October 1930, discovery well is just 1.75 miles away — and still producing for the Hunt Oil Company.

Joe still serves as a symbol for petroleum clubs that “recognize the pioneers of yesterday and today whose perseverance and courage made our nation the world’s leader in petroleum.”

Presented at the annual meeting of the Independent Petroleum Association of America, Joe’s head now sits atop oilfield monuments in Texas: Joinerville (1957), Conroe (1957), Boonsville (1970), and Kilgore (1986) – where he greets visitors to the East Texas Oil Museum.

Joe Roughneck in Joinerville

This, the first Joe Roughneck monument, was erected in Pioneer Park at the Gaston Museum in Joinerville, seven miles west of Henderson. The monument includes a time capsule sealed at the dedication on March 17, 1957, and to be opened in 2056. The capsule reportedly will tell future generations about the East Texas oilfield discovered by Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner in early October 1930.

Joiner’s Daisy Bradford No. 3, discovery well for this prolific field, is nearby – less than two miles from the Gaston Museum. Production from the East Texas field exceeded five billion barrels of oil by 1993. Stripper wells still produce from the field.

Joe Roughneck in Conroe

In Conroe, about 40 miles north of Houston, Joe Roughneck rests on a monument in Candy Cane Park at the Heritage Museum of Montgomery County. He commemorates the discovery of a 19,000-acre field by George Strake in 1931 – “and others who envisioned an empire, dared to seek it, and discovered the Conroe oilfield.”

The Joe Roughneck monument in Conroe, Texas, is next to a miniature derrick protected by Plexiglas — and information about Montgomery County, where “whispers of oil discovery started in the early 1900s.”

The monument recognizes the completion of Strake’s Conroe oil field discovery well in June of 1932. The “Conroe Courier” headlines proclaimed, “Strake Well Comes In. Good for 10,000 Barrels Per Day.”

The Conroe oilfield led to major technology developments after Strake found the oil sands to be natural gas-charged, shallow – and dangerously unstable. By 1993, the 17.000-acre Conroe oilfield will have produced more than 717 million barrels of oil. Read the historical society article Technology and the Conroe Crater.

Joe Roughneck in Boonsville

Governor Preston Smith dedicated Boonsville’s Joe Roughneck on October 26, 1970 – the 20th anniversary of the Boonsville natural gas field discovery.

Joe Roughneck at the East Texas Oil Museum, which opened in 1980 in Kilgore.

The field’s 1945 discovery well, Lone Star Gas Company’s B.P. Vaught No. 1, produced 2.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas in its first 20 years. By 2001, the field – located in the Fort Worth Basin in North-Central Texas – had produced 3.1 trillion cubic feet of gas and 17 million barrels of condensate from 3,500 wells in the field.

Boonsville’s Joe Roughneck statue can be found on Farm to Market Road 920 about 13 miles southwest of Bridgeport in southwestern Wise County.

Joe Roughneck in Kilgore

Kilgore hosts a Joe Roughneck erected on March 2, 1986, in a downtown plaza, celebrating the “boomers” who settled in Kilgore during the 1930s. When Kilgore’s monument committee first approached Lone Star Steel, it learned that the Joe Roughneck cast had been destroyed in a fire. Lone Star Steel allowed use of the original mold to produce the monument.

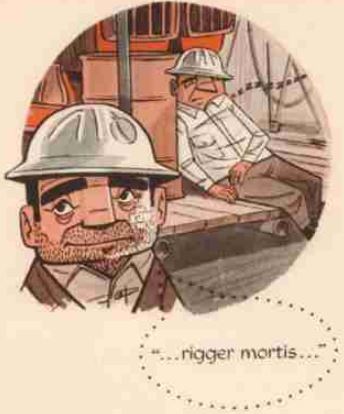

Detail from a 1957 “Joe Roughneck” Lone Star Steel advertisement.

During the East Texas boom, Kilgore had the densest number of wells in the world. Today’s World’s Richest Acre Park displays a pumping unit and the city has restored dozens of derricks from Kilgore’s boomtown birth – a story told at the East Texas Oil Museum.

As the Depot Museum’s exhibit concluded, Joe Roughneck has remained: “Rough and tough, sage and salty, capable and reliable, shrewd but honest. Joe has throughout his lifetime symbolized the determination of the American petroleum industry, reaffirming the indomitable spirit of Chief Roughnecks the world over, past, present and future.”

Joe Roughneck’s iconic advertisement creation should also credit former Lone Star Steel Vice President L.D. “Red” Webster, according to Michael Webb, spouse of Webster’s daughter Rebel Webster (1959-2021). Webb emailed the American Oil & Gas Historical Society and explained he was categorizing unique artifacts and other historic items related to the career of his late wife’s father.

The preserved materials, including “pins, awards, tchotchkes, papers, plaques photos of Red and an original plaster bust of Joe Roughneck,” deserve a museum home, Webb noted. An original of the 12-inch bronze bust also is in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum Institution in Washington, D.C.

View all Chief Roughneck Award Winners from 1955 to 2019.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: A Wildcatter’s Trek: Love, Money and Oil (2016 by 1995 Chief Roughneck Gene Ames Jr.); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “Meet Joe Roughneck.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells, Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/joe-roughneck. Last Updated: October 16, 2024. Original Published Date: March 11, 2005.