Early autos shared unpaved roads with horses and wagons.

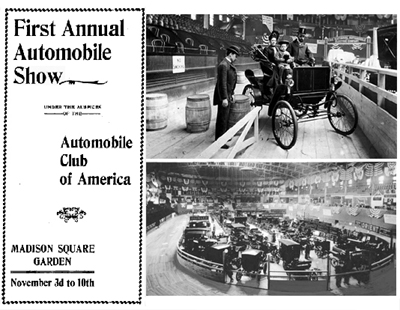

The first U.S. Auto show opened in New York City’s Madison Square Garden in 1900, just five years after Charles Duryea claimed the first American patent for a gasoline-powered automobile. Gas proved to be the least popular source of engine power.

On November 3, 1900, America’s first automobile show presented an innovative assortment of electric, steam, and “internal explosion” engines to power horseless carriages. Manufacturers like Olds Motor Works of Lansing, Michigan, introduced models — one of each kind — to compete in the developing market.

Automobiles powered by internal combustion engines at the 1900 National Automobile Show were primitive. The most popular models proved to be electric, steam, and gasoline…in that order.

From 1901 to 1907, Olds manufactured the “Curved Dash” powered by a single-cylinder, five-horsepower gasoline engine. It sold for $650 and was the first mass-produced U.S. automobile. The concept of automotive assembly lines began when Ransom Olds used a stationary assembly line (Henry Ford would be the first to manufacture cars using a moving line).

Manufacturers presented 160 different vehicles in Madison Square Garden during the first national automobile show, November 3-10, 1900, and sponsored by the Automobile Club of America. Chicago would host its own auto show in 1901.\

Future titans of the transportation industry gave driving and maneuverability demonstrations on a 20-foot-wide track that surrounded the exhibits. A wooden 200-foot ramp tested hill-climbing power.

About 48,000 visitors to the first U.S. auto show paid 50¢ each to see the latest automotive technology. The most popular models proved to be electric, steam and gasoline…in that order.

Electric Autos and “Steamers”

New Yorkers welcomed electric models as a way to reduce the estimated 450,000 tons of horse manure, 21 million gallons of urine, and 15,000 horse carcasses removed from the city’s streets each year.

Hundreds of “Hansom” cabs built by the Electric Vehicle Company worked well, but heavy lead-acid batteries, muddy roads, and lack of electrical infrastructure confined these early electrics to metropolitan areas.

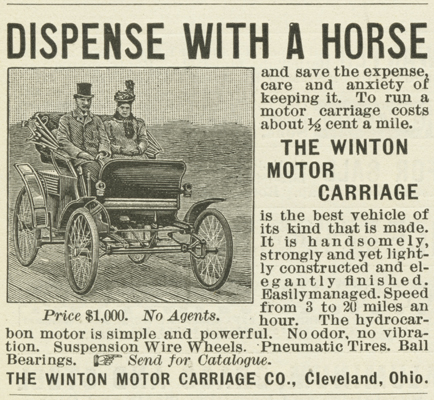

This ad for the Winton motor carriage – often identified as the first American automobile ad, according to the Henry Ford Museum – appeared in an 1898 issue of Scientific American magazine.

Consumers favored “steamers” over their gasoline-powered competitors. Steam-powered automobiles traced their roots back to 1768, when a French military engineer, Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot, built a self-propelled steam tricycle to move artillery.

By 1900, manufacturers like Bridgeport, Connecticut-based Locomobile (from the words locomotive and automobile), Stanley Motor Carriage Company, Tarrytown, New York, and others boasted of their products’ safety and touted the virtues of simple steam power over “complex and sinister” internal combustion engines.

At the time of the first U.S. auto show, Locomobile produced 750 steamers, second in sales only to Columbia & Electric Vehicle Co. of Hartford, Connecticut, but consumers complained of the time required to heat boilers and the necessarily frequent stops for water.

Progress in the development of internal combustion engines soon outpaced steam technology.

At the turn of the century, about 8,000 vehicles shared mostly unpaved roads with horses and wagons. At the first U.S. auto show, an innovative assortment of electric, steam, and “internal explosion” engines powered the latest designs in horseless carriages.

Automobiles powered by internal combustion engines at the 1900 National Automobile Show were primitive, noisy and cantankerous. Most were based on Nikoulas Otto’s 1876 four-stroke design and ran on a variety of “light spirits” such as stove gas, kerosene, naphtha, lamp oil, benzene, mineral spirits, alcohol, and gasoline.

Karl Benz applied for an Imperial patent for his three-wheeled carriage in 1886. It was powered by a one-cylinder, four-stroke gasoline engine. His wife Bertha took it on a widely publicized drive two years later (see First Car, First Road Trip).

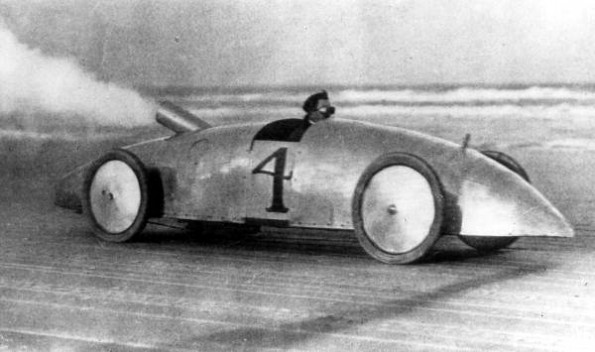

In 1906, a “Stanley Steamer” (above) set the world land speed record at 127.7 m.p.h. – still officially recognized as the land speed record for a steam car.

But in the United States, one critic described the internal combustion engine as “noxious, noisy, unreliable, and elephantine. It vibrates so violently as to loosen one’s dentures. The automobile industry will surely burgeon in America, but this motor will not be a factor.”

Adding Horsepower

The critic was wrong. Gasoline, once an unwanted byproduct of kerosene refining, cost only about 15 cents a gallon in 1900 and produced dramatic increases in engine horsepower. Despite the absence of “filling stations,” gasoline became available in a consumer market where electric lights were making kerosene obsolete.

The refining industry needed a product to replace kerosene and gasoline was it. In 1901, Olds Motor Works sold 425 models of a gasoline-powered “Curved Dash Runabout” for $650 each.

Four years later, when the model was discontinued, almost 19,000 had been sold. America’s consumer preference for gasoline-powered internal combustion engines was thoroughly established.

Many technologies for modern hybrid cars are indebted to Ferdinand Porsche’s 1902 gasoline-electric Mixte.

When New York City hosted its next automobile show in 1901, more than 1,000 vehicles would be on display for one million visitors. Internal combustion and hybrid gasoline-electric automobiles were well represented at the show. The first mass-produced auto, the Curved Dash Oldsmobile (with a horizontal, one-cylinder gasoline engine), made its debut at the show.

America on the Move

A growing number of the new “infernal machines” soon shared unpaved U.S. roads with startled horses. Of the 4,200 new automobiles sold in the United States at the turn of the century, gasoline powered less than 1,000.

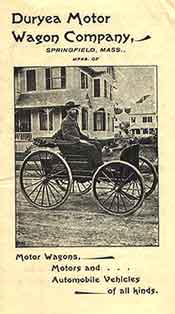

Charles Duryea and his brother Frank in April 1892 had tested a gasoline-powered automobile built in their Springfield, Massachusetts, workshop. Considered the first automobile regularly made for sale in the United States, 13 of the model were manufactured by the Duryea Motor Wagon Company.

Although their company would last only three years, according to the Henry Ford Museum, the Duryea brothers became the first Americans to attempt to build and sell automobiles at a profit. Other manufacturers quickly followed the Duryea example.

By the time Henry Ford sold his first “quadri-cycle” in 1896, New York City public workers were removing 450,000 tons of horse manure from the streets every year.

Two months after the Duryea Company’s first sale in 1896, a New York City motorist driving a Duryea reportedly hit a bicyclist. This was recorded as the nation’s first automobile traffic accident.

The Ford Model T “Tin Lizzy,” the first mass-produced car the average American buyer could afford, first rolled off its production line on October 1, 1908.

“Petroleum, which consists of crude oil and refined products such as gasoline, diesel, and propane, is the largest primary source of energy consumed in the United States, accounting for 36 percent of total energy consumption in 2018…More than two-thirds of finished petroleum products consumed in the United States are used in the transportation sector.” — U.S. Energy Information Administration, Today in Energy, August 2019.

In 2003, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., opened a major exhibition about the role of transportation in society (see American on the Move). The National Museum of American History’s collection includes the history of Route 66, the U.S. interstate system, and the evolving technologies of cars.

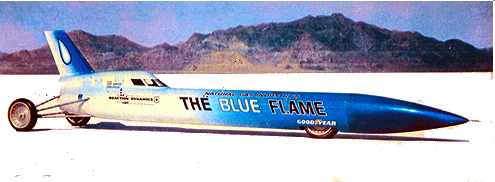

A rocket motor fueled by natural gas powered the Blue Flame to a world land speed record in October 1970 that would stand for more than a decade.

Learn how liquified natural gas (LNG) fueled a 1970 land world speed record in Blue Flame Natural Gas Rocket Car.

Electric Cars: Back to the Future

“The available supply of gasoline, as is well known, is quite limited, and it behooves the farseeing men of the motor car industry to look for likely substitutes.” – Horseless Age, 1905

More than a century ago, “automotive engineers” examined novel ways of combining electric motors and gasoline engines to exploit the strengths and minimize the weaknesses of each.

Electric cars once were practical on level roads — even with their mammoth lead-acid batteries and limited range — but were largely confined to big cities where recharging infrastructure was available. Twenty-first-century hybrid cars emulate their predecessors.

“In this system, an electric generator or dynamo is coupled direct to the petrol motor, and the current furnished is employed to operate electric motors which drive the car,” noted Paul Hasluck in his 2015 book The Automobile: A Practical Treatise on the Construction of Modern Motor Cars – Steam, Petrol, Electric, and Petro-Electric (from a 1923 French book by Gerard Lavergne).

Modern hybrids are much indebted to Ferdinand Porsche’s 1902 gasoline-electric Mixte. The Mixte used a small four-cylinder gasoline engine to generate electricity – but not to turn its wheels. The engine powered two three-horsepower electric motors mounted in the Mixte’s front wheel hubs that could briefly surge to seven horsepower and carry it to a top speed of 50 mph.

While more than a century of technological evolution separates Mixte from today’s hybrids, both rely upon gasoline to enhance and recall the virtues of “electrics” as automobiles with a future.

Learn much more about internal combustion engine history by visiting the New England Auto Museum and see many rare early examples preserved at the Cool Coolspring Power Museum.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Automobile: A Practical Treatise On the Construction of Modern Motor Cars Steam, Petrol, Electric and Petrol-Electric (2015); A History of General Motors (1992); A History of the New York International Auto Show: 1900-2000 (2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Cantankerous Combustion — First U.S. Auto Show.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/first-auto-show. Last Updated: October 23, 2024. Original Published Date: March 1, 2008.