by Bruce Wells | Jun 28, 2025 | Petroleum in War

Navy admirals reluctantly switched from coal to oil — adding engine power and simplifying resupply.

Commissioned on March 12, 1914, the USS Texas was the last American battleship built using engines with coal-fired boilers. Converted to burn fuel oil in 1925, the “Mighty T” became even more dominant at sea during the worldwide maritime change from coal to oil power.

When the Industrial Revolution ended the “Age of Sail,” supplies of coal that fired the boilers of steam-powered ships became a strategic resource. Worldwide “coaling stations” were essential at a time when oil was used as an axle grease or resource for making lamp kerosene. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | May 29, 2025 | Petroleum in War

“Conundrums” spooled petroleum pipelines across the English Channel after D-Day.

Secret pipelines unwound from massive spools to reach French ports and transport vital oil across the English Channel after the June 6, 1944, D-Day landings.

Wartime planners knew that following the Normandy invasion, Allied forces would need vast quantities of petroleum to continue the advance into Europe. The Allies also knew any tankers trying to reach French ports would be vulnerable to Luftwaffe attacks. A secret plan relied on new undersea pipeline technologies. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | May 1, 2025 | Petroleum in War

Rebel cavalry in 1863 raided Burning Springs — the first oilfield attack in war.

After burning oilfield facilities at a creek in northwestern Virginia (soon to be West Virginia), Confederate Cavalry Gen. William “Grumble” Jones reported to Gen. Robert E. Lee: “Men of experience estimated the oil destroyed at 150,000 barrels. It will be many months before a large supply can be had from this source…”

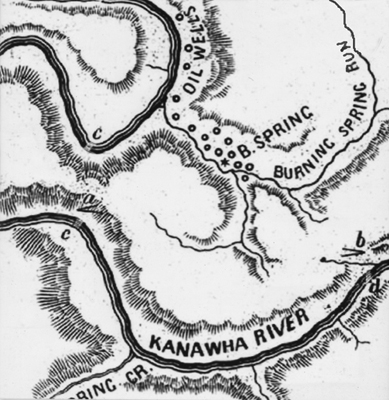

On May 9, 1863, the booming oilfield community at Burning Springs fell to the rebel cavalry raiders led by Gen. Jones. His four regiments of Virginia cavalry burned cable-tool drilling derricks, production equipment, storage tanks, and thousands of barrels of oil.

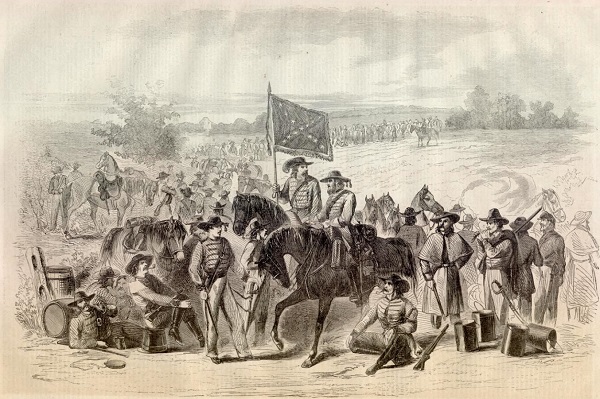

“The First Virginia (Rebel) cavalry at halt. Sketched from nature by Mr. A. R. Waud.” From Harper’s Weekly, September 27, 1862. Gen. Jones’ Brigade consisted of the 6th, 7th, 11th, 12th Virginia Cavalry Regiments and the 35th Virginia Cavalry Battalion. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

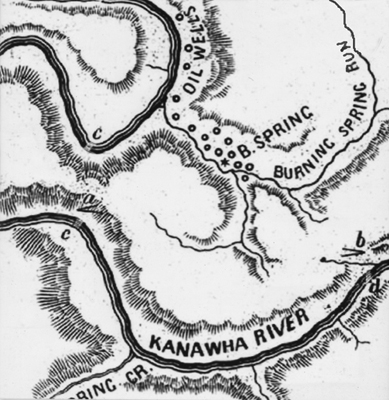

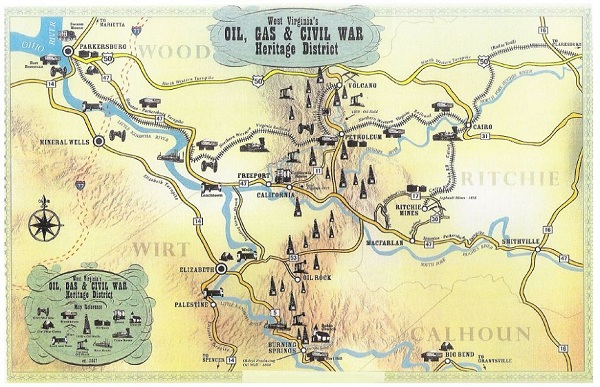

The surprise attack south of Parkersburg along the Kanawha River by Gen. Jones marked the first time an oilfield was targeted in war, “making it the first of many oilfields destroyed in war,” proclaimed oil historian and author David L. McKain (1934-2014) in Where it All Began: The story of the people and places where the oil & gas industry began: West Virginia and southeastern Ohio.

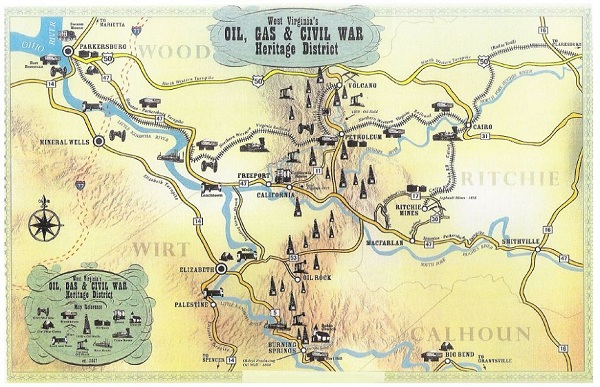

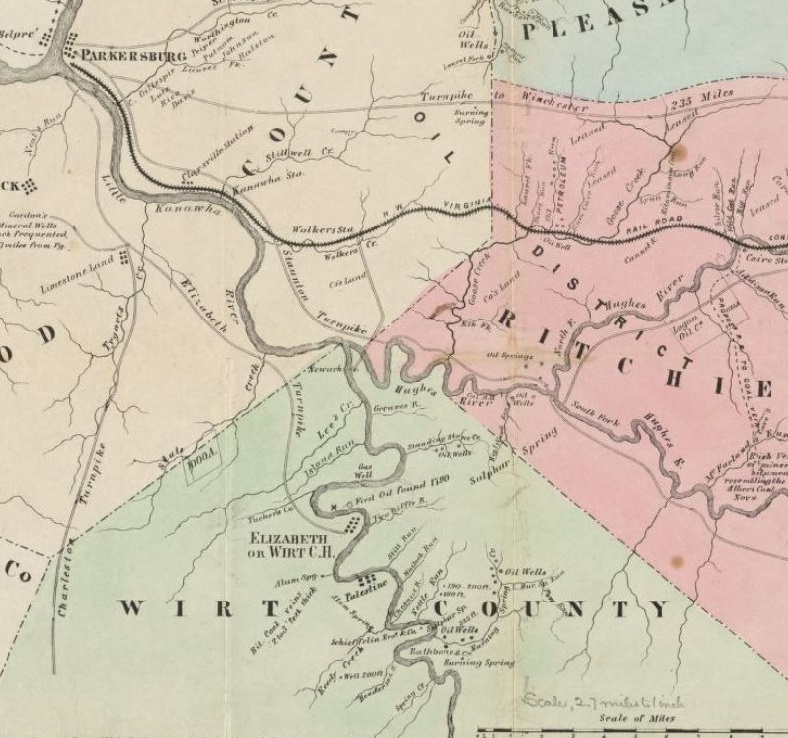

The Burning Springs oilfield (near Elizabeth) was destroyed by Confederate raiders in May 1863 when Gen. William “Grumble” Jones and 1,300 troopers attacked in what some call the first oilfield destroyed in a war. Map courtesy Oil & Gas Museum, Parkersburg, West Virginia.

According to McKain’s 1994 book, after the oilfield attack, Gen. Jones reported his cavalry troops left rows of burning oil tanks, a “scene of magnificence that might well carry joy to every patriotic heart.”

Making West Virginia

“After the Civil War, the industry was revived and over the next fifty years the booms spread over almost all the counties of the state,” explained McKain, who from 1970 to 1991 was president of Acme Fishing Tool Company, founded by his grandfather at the height of West Virginia’s oil and natural gas boom in 1900.

A drilling boom began at Burning Springs when an 1861 well produced 100 barrels of oil a day.

McKain, who established an oil museum in Parkersburg, spent decades collecting artifacts on display in the former company warehouse. He was often seen driving his black truck loaded with muddy, early 20th century oilfield engines and other equipment.

Once often seen driving his pickup loaded with historic oilfield equipment, David McKain founded a Parkersburg oil museum — and built exhibits at Burning Springs. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Almost a century before the Civil War, George Washington had acquired 250 acres in the region because it contained oil and natural gas seeps. “This was in 1771, making the father of our country the first petroleum industry speculator,” he noted. The Parkersburg historian authored several books, including a detailed history of the West Virginia petroleum industry.

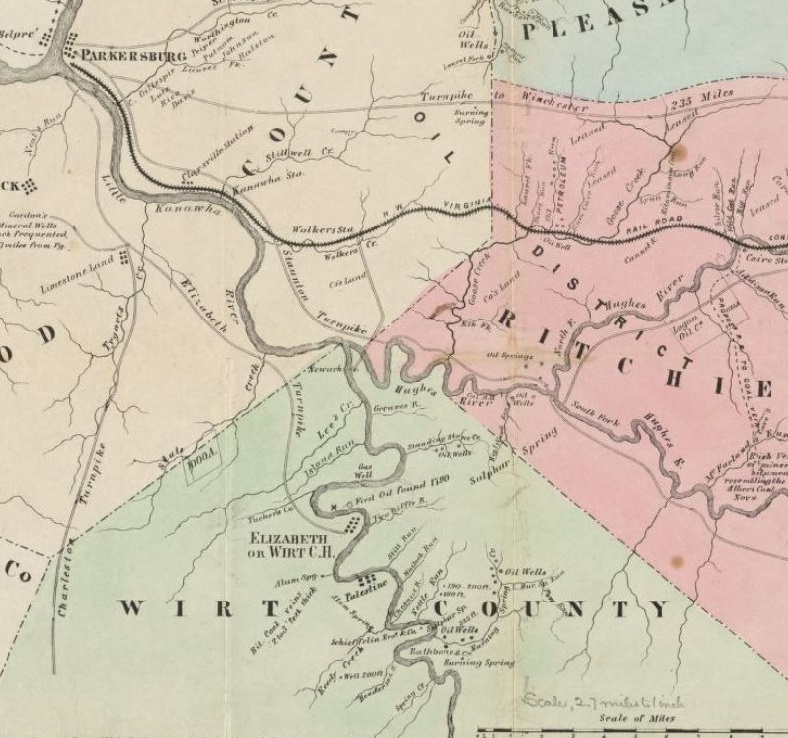

Detail from 1864 “Map of the oil district of West Virginia,” including Burning Springs (at Elizabeth) in Wirt County courtesy Norman B. Leventhal Map Center Collection, Boston Public Library.

As early as 1831, natural gas was moved in wooden pipes from wells to be used as a manufacturing heat source by the Kanawha salt manufacturers.

Rathbone Well and Statehood

Modern West Virginia’s petroleum industry began when it was part of Virginia. John Castelli ”Cass” Rathbone produced oil from an 1861 well drilled near Burning Springs Run in what today is West Virginia. His well had reached 300 feet and began producing 100 barrels of oil a day.

Rathbone drilled more wells along the Kanawha River south of Parkersburg — beginning the first petroleum boom to take place outside the Pennsylvania oil regions

In 1861, at Burning Springs, Rathbone had used a spring pole — an ancient drilling technology — to drill to a depth of 303 feet, and the well began producing 100 barrels of oil a day. Soon, a commercial oil industry began in the towns of Petroleum and California near Parkersburg, which later became a center for oilfield service and supply companies.

The Rathbone well and commercial oil sales at Petroleum marked the true beginnings of the oil and gas industry in the United States, according to McKain.

David L. McKain established the Oil and Gas Museum at 119 Third Street in Parkersburg, West Virginia. As early as 1831, local salt manufacturers used natural gas as a heat source. Photo by Bruce Wells.

McKain, the founder of the Oil and Gas Museum in Parkersburg, maintained that the wealth created by petroleum was the key factor for bringing statehood to West Virginia during the Civil War.

“Many of the founders and early politicians were oil men — governor, senator and congressman — who had made their fortunes at Burning Springs in 1860-1861,” McKain explained.

President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation admitting the state on June 20, 1863.

Grumble burns an Oilfield

When Confederate Gen. William “Grumble” Jones and 1,300 troopers attacked Burning Springs in the spring of 1863, they destroyed equipment and thousands of barrels of oil.

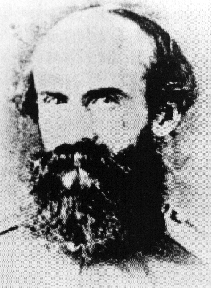

Confederate cavalry Gen. William “Grumble” Jones.

“The wells are owned mainly by Southern men, now driven from their homes, and their property appropriated either by the Federal Government or Northern men,” said Gen. Jones of his raid on the early oil boom town.

Gen. Jones officially reported to Gen. Robert E. Lee: All the oil, the tanks, barrels, engines for pumping, engine-houses, and wagons — in a word, everything used for raising, holding, or sending it off was burned. Men of experience estimated the oil destroyed at 150,000 barrels. It will be many months before a large supply can be had from this source, as it can only be boated down the Little Kanawha when the waters are high.

The West Virginia Oil and Gas Museum was established thanks to David McKain, who added a small museum at the site of Burning Springs and an oil history park at California (27 miles east of Parkersburg on West Virginia 47). In addition to his Where It All Began, McKain in 2004 published The Civil War and Northwestern Virginia.

Learn more about petroleum’s strategic roles in articles linked at Oil in War.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Civil War and Northwestern Virginia — The Fascinating Story Of The Economic, Military and Political Events In Northwestern Virginia During the Tumultuous Times Of The Civil War (2004). Where it All Began: The story of the people and places where the oil & gas industry began: West Virginia and southeastern Ohio (1994). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1994). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Confederates attack Oilfield.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/confederates-attack-oilfield. Last Updated: May 1, 2025. Original Published Date: May 5, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 13, 2025 | Petroleum in War

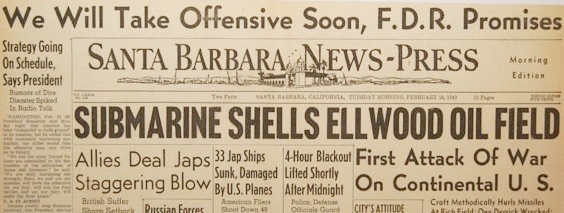

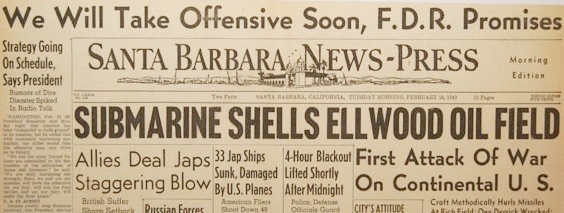

Shelling of the Ellwood field at Santa Barbara created mass hysteria — and the “Battle of Los Angeles.”

Soon after America entered World War II, an Imperial Japanese Navy submarine attacked a refinery and oilfield near Los Angeles, the first attack of the war on the continental United States. The submarine’s deck gun fired about two dozen rounds, causing little damage — but it resulted in the largest mass sighting of UFOs in American history.

A February 1942 Imperial Japanese Navy submarine’s shelling of a California refinery caused little damage but created invasion (and UFO) hysteria in Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Goleta Valley Historical Society.

At sunset on February 23, 1942, Imperial Japanese Navy Commander Kozo Nishino and his I-17 submarine lurked 1,000 yards off the California coast. It was less than three months since the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Los Angeles residents were tense. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Nov 4, 2024 | Petroleum in War

Secret WWII project sent Oklahoma drillers to British oilfield, adding one million barrels of oil production by 1944.

As the United Kingdom fought for its survival during World War II, a team of American oil drillers, derrickhands, roustabouts, and motormen secretly boarded the converted troopship HMS Queen Elizabeth in March 1943. Once their story was revealed years later, they would become known as the Roughnecks of Sherwood Forest.

The 42 volunteers from Noble Drilling and Fain-Porter Drilling companies taken before they secretly embarked for the United Kingdom on March 12, 1943, aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth, which had been converted into a troop transport ship. Photo courtesy of the Guy Woodward Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

By the summer of 1942, the situation was desperate. The future of Great Britain — and the outcome of World War II — depended on the supply of petroleum. At the end of that year, demand for 100-octane fuel had grown to more than 150,000 barrels every day — and German U-boats ruled the Atlantic.

British Secretary of Petroleum, Geoffrey Lloyd in August 1942 called for an emergency meeting of his country’s Oil Control Board to assess the “impending crisis in oil.” (more…)