by Bruce Wells | Aug 1, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

A flammable workplace brings danger everywhere.

Whether ignited by accident, natural phenomena, or acts of war, oilfield fires have challenged the petroleum industry since the earliest wells. Catastrophic fires — and technologies needed to fight them — began with the first U.S. well, completed on August 27, 1859, at Oil Creek in northwestern Pennsylvania.

Just six weeks after his discovery, Edwin L. Drake’s well caught fire when driller William “Uncle Billy” Smith inspected the well with an open lamp, igniting seeping natural gas. Flames consumed the cable-tool derrick, engine-pump house, stored oil, and Smith’s nearby shack.

Drake Well Museum exhibits at Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, include a replica of the cable-tool derrick and engine house that drilled the first U.S. well in 1859.

Today, visitors to the Drake Well Museum at Titusville tour the latest reconstructed cable-tool derrick and its engine house along Oil Creek, where the former railroad conductor found oil at a depth of 69.5 feet. He revealed a geologic formation later called the Venango sandstone.

Another Drake Well Museum exhibit preserves the Titusville Fire Department’s coal-fired steam pumper (see Oilfield Photographer John Mather). As the new U.S. petroleum industry learned from hard experience, firefighting technologies evolved in northwestern Pennsylvania’s “Valley that Changed the World.”

Hard Lessons

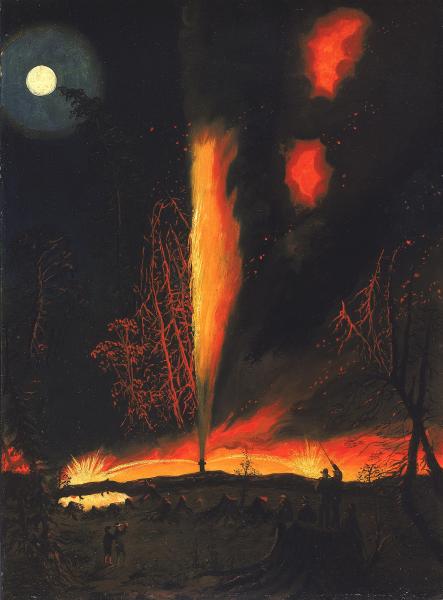

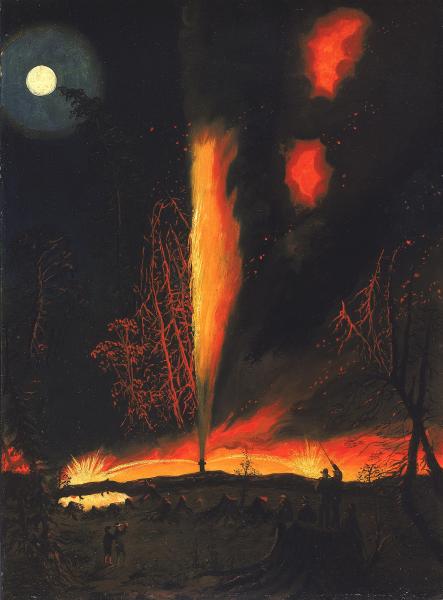

In 1861, an explosion and fire at Henry Rouse’s gushing oil well made national news when he was killed along with 18 workers and onlookers (see Rouseville 1861 Oil Well Fire). In 1977, the Smithsonian American Art Museum acquired landscape artist James Hamilton’s “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” painted soon after the fire.

The dangerous operating environment of a cable-tool rig included a spinning bull wheel, a rising and falling heavy wooden beam, a steam boiler, and crowded spaces.

The pounding iron drill bit frequently needed to be withdrawn and hammered sharp using a small, but red-hot forge, often set up just feet from the wellbore.

Lighting striking derricks and oilfield tank farms also would prove challenging.

Preserved by the Smithsonian, “Burning Oil Well at Night, near Rouseville, Pennsylvania,” circa 1861, an oil painting by James Hamilton, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Late 19th-century oilfield fire prevention remained rudimentary as exploration moved westward. Safety lamps like one with two spouts, popularly known as the “Yellow Dog” lantern, were not particularly safe. The rapidly growing petroleum industry needed new technologies for preventing fires or putting them out.

As drilling experience grew, refineries responded to skyrocketing public demand for the lamp fuel kerosene. Production from new oilfields in Texas, Kansas, and Oklahoma led to construction of safer storage facilities, but advances in drilling deeper wells brought fresh challenges (see Ending Oil Gushers – BOP).

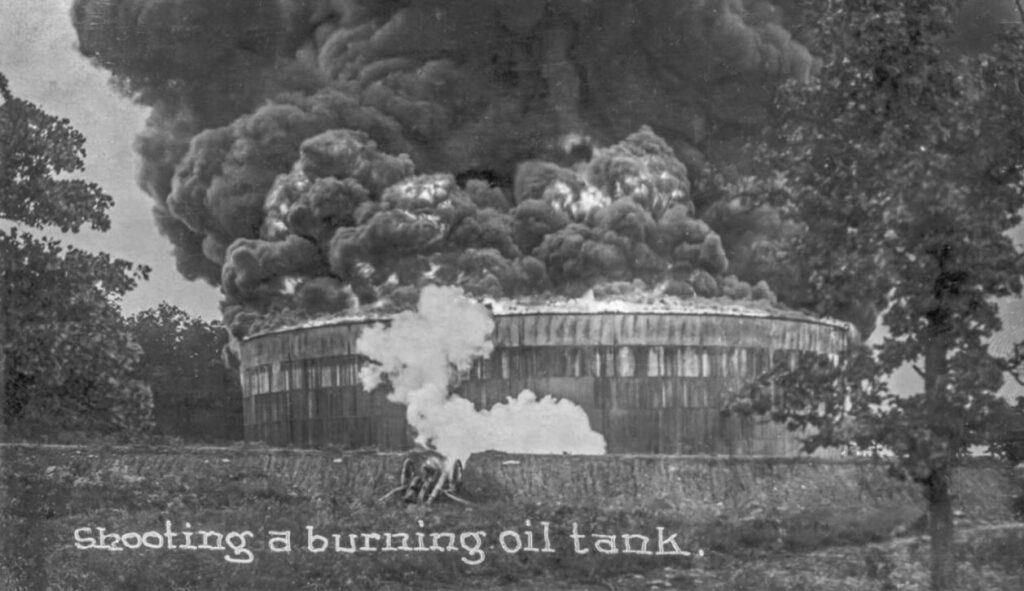

Firefighting with Cannons

Especially in early oilfields, working in such a flammable workplace could bring danger from everywhere — including the sky. Lightning strikes on wooden storage tanks created flaming cauldrons.

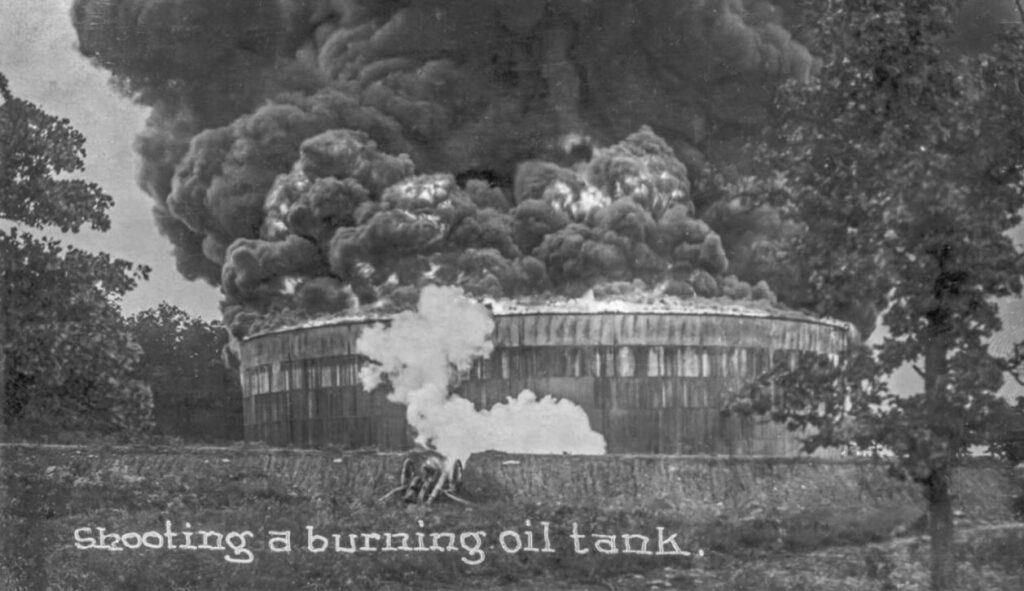

A circa 1915 photo of a cannon — possibly a “Model 1819,” according to The Artilleryman Magazine (Fall 2019, vol. 40, no. 4) — firing solid shot in an attempt to create a hole to drain the burning oil tank. “No one appears to be near the gun, so it may have been fired using fuse or electrically.” Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

In the rush to exploit early oilfields, wooden derricks crowded an oil-soaked landscape, leaving workers — and nearby towns — dangerously exposed to an accidental conflagration. Many oil patch community oil museums have retained examples of early smooth-bore cannon used to fight fires.

A Civil-War era field cannon exhibit in Corsicana, Texas, tells the story of a cannon from the Magnolia Petroleum Company tank farm. “It was used to shoot a hole in the bottom of the cypress tanks if lightning struck,” a plaque notes. “The oil would drain into a pit around the tanks and be pumped away.”

Learn more in Oilfield Artillery fights Fires.

Oilfield firefighting using cannons has continued into the 21st century. In May 2020, a well operated by the Irkutsk Oil Company in Russia’s Siberian region ignited a geyser of flaming oil and natural gas. When efforts to control the blowout failed, the Russian Defense Ministry flew in a 1970s anti-tank gun and its Hungarian crew.

From about 200 yards away, the Hungarian artillerymen (Covid-19 masked) repeatedly fired their 100-millimeter, smooth-bore Rapira MT-12 gun at blazing oilfield equipment, “breaking it from the well and allowing crews to seal the well,” according to the Russian Defense Ministry.

In addition to using cannons to fire well fires, other techniques have included smothering them using cranes to lower iron metal caps (see Kansas Gas Well Fire) or detonating an explosive from above to rob the flames of air. Using a wind machine must count among the more unusual methods.

Firefighting with Wind

In 1929, about 400 volunteers took on a raging oilfield fire that had destroyed seven derricks and two oil well “heavy producers” at Santa Fe Springs, California. “Roaring Flames Turn Black Gold To Smoke,” proclaimed a Los Angeles Times headline on June 12.

The Santa Fe Springs Hathaway Ranch and Oil Museum, “a museum of five generations of Hathaway family and Southern California history,” has preserved rare motion picture clips of a propeller-driven “Wind-making Machine” in action — although the wind proved no match for the flames.

“The machine that made the wind that conquered a fire in a Santa Fe Springs oilfield on June 15, 1929,” used a three-bladed airplane propeller and a powerful motor to blow heat away from the men at work fighting the fire. “A track of boards was built for the machine over a lake of oil, mud and water in the ‘hot zone’ of the big fire.” — Hathaway Ranch and Oil Museum, Santa Fe Springs, California.

The fire depicted in the silent film is intense, “so firefighting equipment is appropriately distant from the well head, including the wind machine,” explained museum Curator of Media Archives Terry Hathaway.

“It looks like its use is more or less limited to blowing hot air, smoke and steam (from firefighting water hoses) away from the workers and toward the fire,” he added.

Hathaway explained that the wind machine on the back of a truck probably had no direct influence on the fire itself, due to distance and the ferocity of the high-pressure well blowout, “but it apparently may have made things more tenable for the firefighters by keeping them relatively cool and smoke free.”

A modern version of the 1929 wind-making machine returned in 1991, after Saddam Hussein’s retreating Iraqi army set hundreds of wells ablaze in Kuwait oilfields. Firefighting technologies by then had evolved into using jet engines. MB Drilling Company of Szolnok, Hungary, sent a three-man team with “Big Wind,” a modern version of the 1929 wind-making machine.

Instead of a piston-driven propeller on a vintage truck bed, twin MIG-21 turbojets were mounted in place of the turret on a World War II Soviet T-34 tank. The jet engines generated 700 mph of thrust, which blasted hundreds of gallons of water per second into the flames.

Image from Romanian video of 1991 Kuwaiti oilfields: “Twin MIG-21 turbojets mounted on a World War II era Soviet T-34 tank dubbed ‘Big Wind’ generated 700 mph thrust blasting hundreds of gallons of water per second into the fire.”

The Hungarian team members put out their assigned fires and recapped nine wells in 43 days, according to a 2001 Car and Driver article, “Stilling the Fires of War.”

“Hell Fighters”

Many firefighting teams went to Kuwait following the Persian Gulf War, including Paul “Red” Adair, whose dramatic oilfield feats had been popularized in the 1968 movie “Hellfighters.” Adair and his team extinguished 117 Kuwaiti oil well fires by robbing the flames of oxygen using explosives.

As the Hungarian crew chief of “Big Wind” observed at the time, “Would you really want to walk up to a 2,000-degree flame through burning heat and oil rain carrying explosives?”

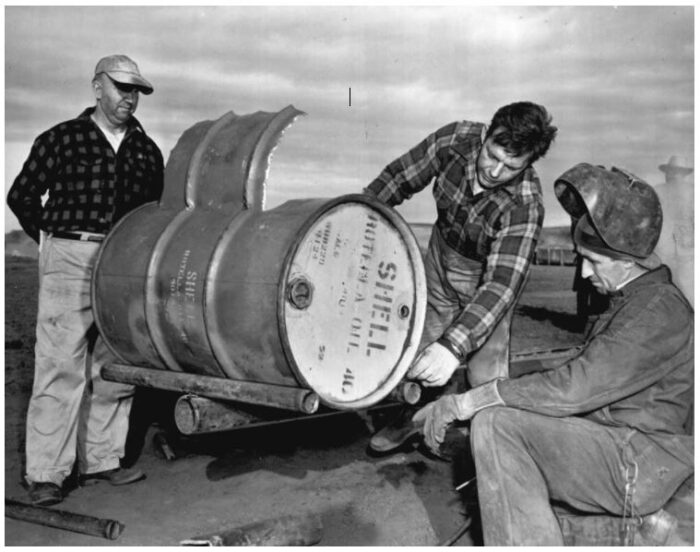

A century earlier, Karl T. Kinley did just that. Kinley, a California oil well “shooter” (see Shooters — A History of Fracking) during the early 1900s, learned from first-hand experience that a dynamite explosion could “blow out” a wellhead fire. Kinley’s son, Myron Macy Kinley, established the oilfield service business M.M. Kinley Company after learning from his father’s highly dangerous experiments.

Readers Digest in 1953 declared Myron M. Kinley “the unrivaled world-champion fighter of oil fires.” A TIME article described him as “the indispensable man of the oil industry.”

But with the chance of terrible injuries or death ever present, firefighting success was not without cost. Kinley’s brother Floyd was killed by falling rig debris in 1938 as they fought a runaway well fire near Goliad, Texas.

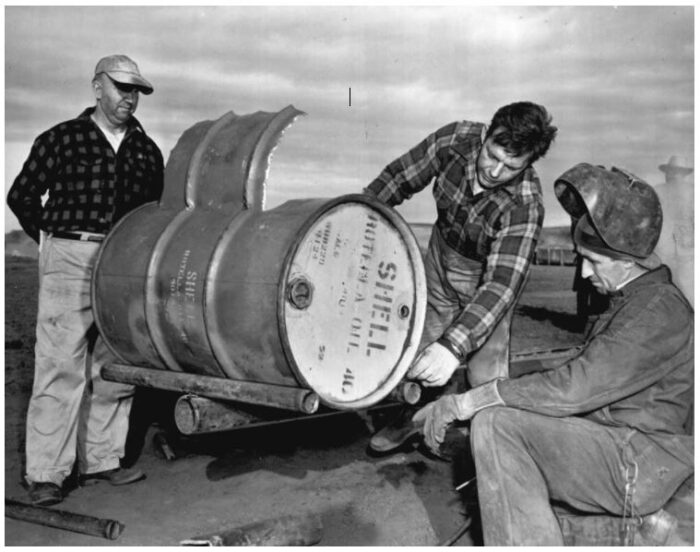

Myron M. Kinley (at left), Paul “Red Adair (center), and a welder examine a nitroglycerin bomb barrel. Myron Kinley has been called the grandfather of modern oil well fire fighting, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. Photo by A.Y. Owen courtesy OHS Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection.

Kinley, a mentor of “Red” Adair, developed technologies at M.M. Kinley Company that inspired other firefighting experts, including Joe R. Bowden Sr., who founded Wild Well Control in 1975 to provide emergency response, safety training, and relief well engineering.

After they had worked for the Red Adair Service and Marine Company, Asger “Boots” Hansen and “Coots” Mathews opened an office in Houston in 1978 for what could become Boots & Coots International Well Control (today a Halliburton Company).

Other oilfield pioneers include Cudd Pressure Control — today, Cudd Well Control, founded by Bobby Joe Cudd, another pioneer of emergency well control techniques. Cudd established his Woodward, Oklahoma-based company in 1977 with eight employees and a “hydraulic snubbing unit.”

Adair had joined Myron Kinley’s California oilfield service company after serving with a U.S. Army bomb disposal unit during World War II. After starting his own company in 1959, “Red” improved firefighting technologies, developing new tools, equipment, and techniques for “wild well” control.

Adair was 75 years old when he successfully tamed roaring fires in Kuwait’s scorched oilfields. As early as 1962, his Red Adair Company had “put out a Libyan oil well fire that had burned so brightly that astronaut John Glenn could see it from space,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

USSR Firefighting Nukes

Between 1966 and 1981, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics snuffed out runaway fires at natural gas wells using subsurface nuclear detonations. The experiments, part of the broader “Program No. 7 – Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy,” imitated a U.S. initiative, “Plowshare,” seeking peaceful uses of nuclear bombs (see Project Gasbuggy tests Nuclear “Fracking”).

According to the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, USSR scientists code-named five secret attempts: Urta-Bulak, Pamuk, Crater, Fakel, and Pyrite.

The first experimental detonation, Urta-Bulak in 1966, came after three years and failed conventional attempts to extinguish a blazing natural gas well in Southern Uzbekistan. Scientists positioned a special 30-kiloton package within 300 feet of the borehole by slant drilling.

Detonated in clay strata at a depth of 4,921 feet, the nuclear explosion’s shock wave sealed the well within 23 seconds, staunching the daily waste of 423 million cubic feet of natural gas, reported Russian television.

Video image showing a USSR nuclear device being lowered into well for a detonation shockwave to extinguish a runaway oilfield fire. A Russian newspaper reported a 1966 nuclear blast used to put out a natural gas well fire in Uzbekistan.

In 1968, the Pamuk well explosion used a larger, 47-kiloton nuclear device that measured 9.5 inches by 10 feet. Two years of uncontrolled natural gas and a heavily saturated surrounding landscape yielded to the nuclear detonation at a depth of 8,000 feet. The runaway gas well died out seven days later.

Twice in 1972, USSR scientists used lower-yield detonations to extinguish massive fires. The smallest of the nuclear firefighting devices (3.8 kiloton) on July 7 squelched a runaway gas well fire in Ukraine, about 12 miles north of Krasnograd.

The USSR program’s only recorded failure came in 1981 with the last Soviet use of firefighting nukes. On May 5, a nuclear device failed to shut down a 56 million cubic feet per day out-of-control natural gas well. The code-named Pyrite device had been positioned proximate to the well at a depth of 4,957 feet.

The 37.6-kiloton detonation in a sandstone-clay formation failed to seal the gas well, according to the USSR Ministry of Defense, which provided little more information.

By the 1950s, America was considering how to use nuclear weapons for constructive purposes — “Atoms for Peace.” In December 1961, the Plowshare Program began examining the feasibility of various projects, including the Project Gasbuggy tests to improve natural gas production. Those tests worked, but yielded radioactive gas.

Neither the Project Plowshare nor the Soviet Union’s Program No. 7 produced desirable results. With or without nukes, oilfield work then and now remains among the most dangerous jobs in the world. Safety and prevention methods have improved along with the technologies since the industry’s earliest wells in northwestern Pennsylvania.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Exploring Oilfield Firefighting Technologies.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/oilfield-firefighting-technologies. Last Updated: August 1, 2025. Original Published Date: January 31, 2022.