by Bruce Wells | Jul 13, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

As the U.S. petroleum industry expanded following the January 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill in Texas, service company pioneers like Carl Baker and Howard Hughes brought new technologies to oilfields.

Baker Oil Tools and Hughes Tools specialized in maximizing petroleum production, as did oilfield service company competitors Schlumberger, a French company founded in 1926, and Halliburton, which began in 1919 as a well-cementing company.

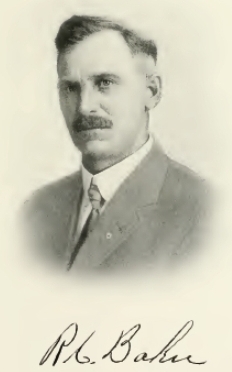

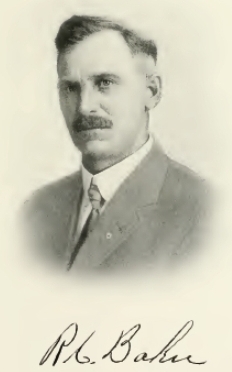

R.C. “Carl” Baker Sr.

Baker Oil Tool Company (later Baker International) had been founded by Reuben Carlton “Carl” Baker Sr., who among other inventions patented a cable-tool drill bit in 1903 after founding the Coalinga Oil Company in Coalinga, California.

A 1919 portrait of Baker Tools Company founder R.C. “Carl” Baker (1872 – 1957).

The oil wells Carl Baker had drilled near Coalinga encountered hard rock formations that caused problems with casing, so he developed an offset cable-tool bit allowing him to drill a hole larger than the casing. He also patented a “Gas Trap for Oil Wells” in 1908, a “Pump-Plunger” in 1914, and a “Shoe Guide for Well Casings” in 1920.

Coalinga was “every inch a boom town and Mr. Baker would become a major player in the town’s growth,” according to the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum. He also organized several small oil companies and the local power company and established a bank.

After drilling wells in the Kern River oilfield, Baker added to his technological innovations on July 16, 1907, when he was awarded a patent for his Well Casing Shoe (No. 860,115), a device ensuring uninterrupted flow of oil through a well. His invention revolutionized oilfield production.

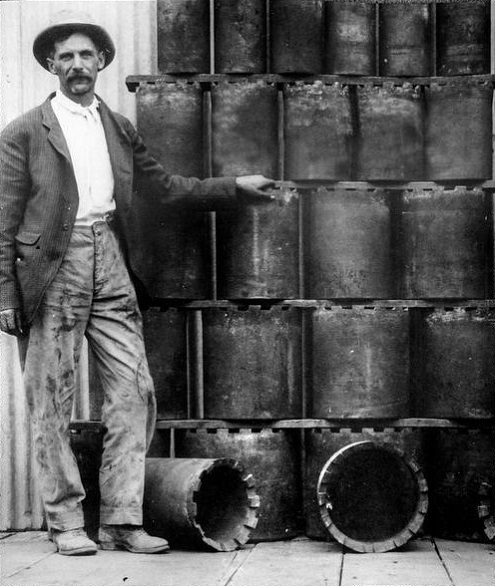

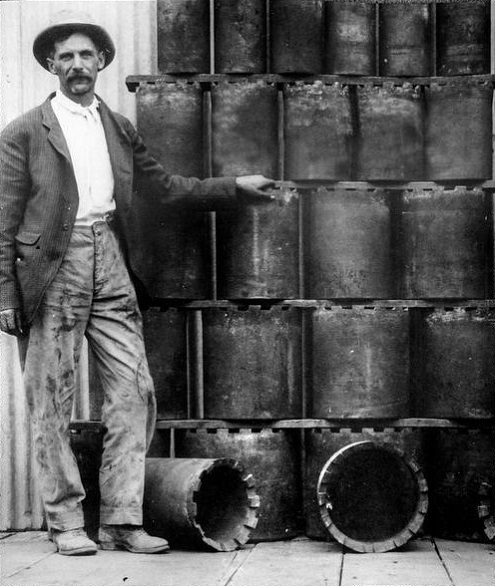

R.C. “Carl” Baker standing next to Baker Casing Shoes in 1914. Photo courtesy R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

In 1913, Baker organized the Baker Casing Shoe Company (renamed Baker Tools two years later). He opened his first manufacturing plant in Coalinga.

When Baker Tools headquarters moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s, the building remained a company machine shop. It was donated by Baker to Coalinga in 1959. Two years later, the original machine shop and office of Baker Casing Shoe reopened as the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

By the time Carl Baker Sr. died in 1957 at age 85, he had been awarded more than 150 U.S. patents in his lifetime. “Though Mr. Baker never advanced beyond the third grade, he possessed an incredible understanding of mechanical and hydraulic systems,” reported the former Coalinga museum.

Baker Tools became Baker International in 1976 and Baker Hughes after the 1987 merger with Hughes Tool Company.

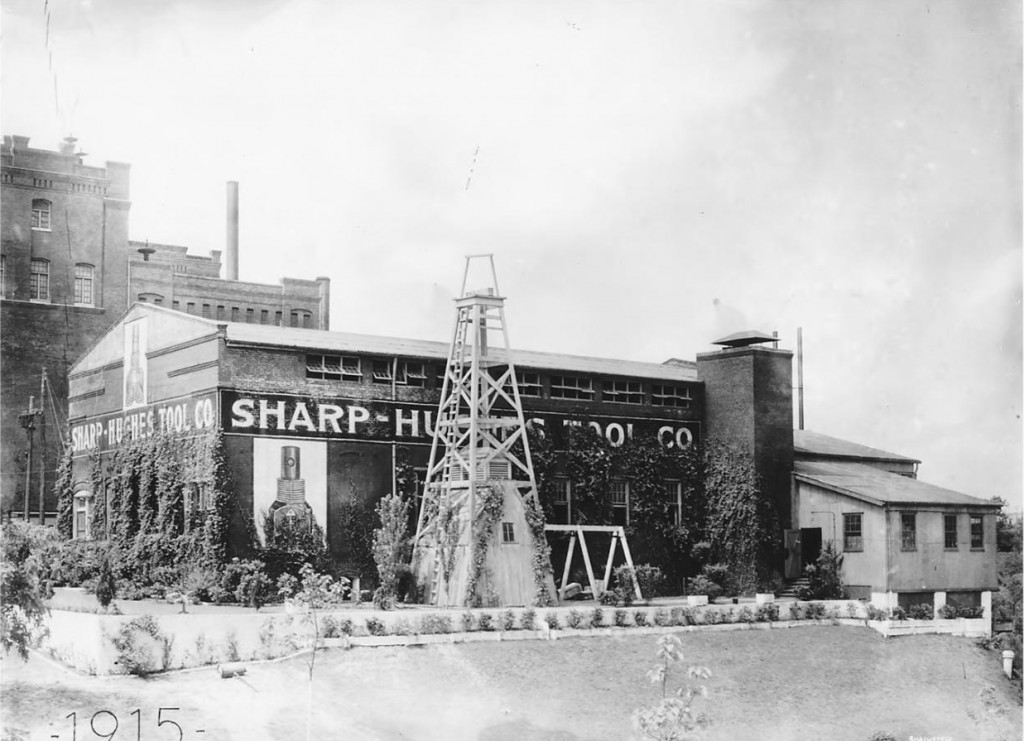

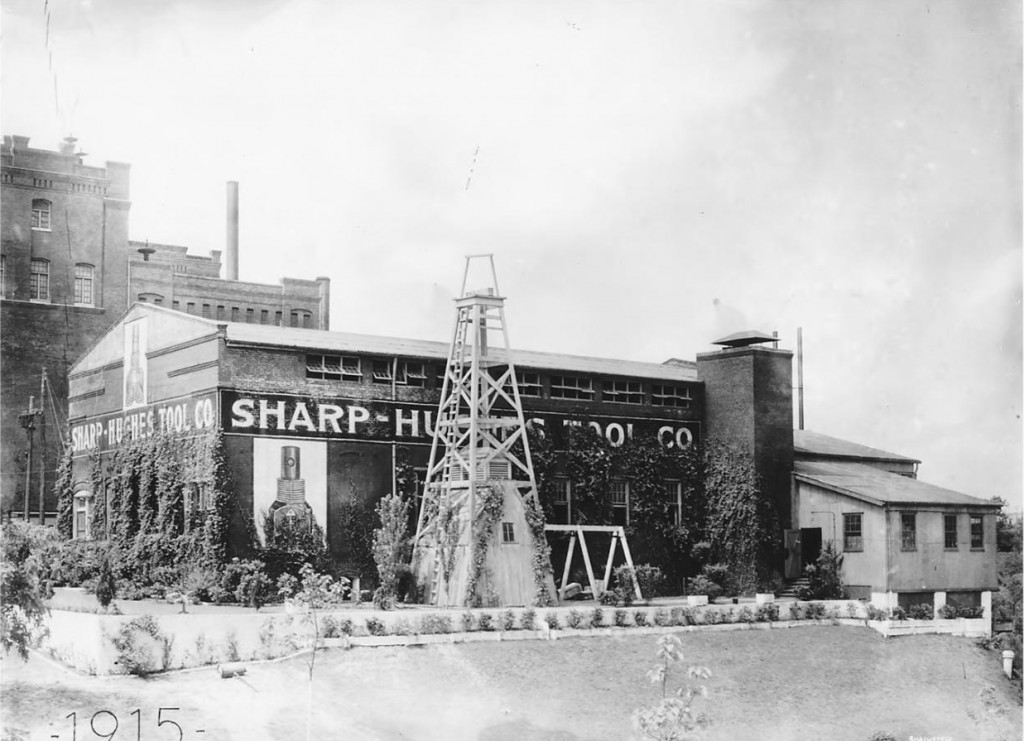

The Houston manufacturing operations of Sharp-Hughes Tool at 2nd and Girard Streets in 1915. The site is on the campus of the University of Houston–Downtown. Photo courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library.

Howard Hughes and Walter Sharp

The Hughes Tool Company began in 1908 as the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company, founded by Walter B. Sharp (1870–1912) and Howard R. Hughes, Sr.

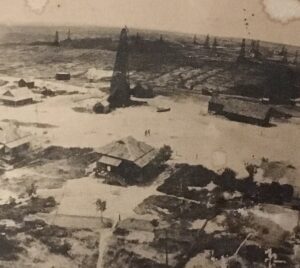

Sharp was an experienced Texas oilfield pioneer who in 1893 drilled for the Gladys City Oil and Gas Manufacturing Company at Beaumont, Texas. The exploratory well on Spindletop Hill did not find oil, but it helped lead to the giant oilfield’s discovery in 1901, according to Texas State Historical Association (TSHA).

In 1896, Sharp was one of the drillers at Corsicana when the state’s first commercial oilfield was developed. While there, he met Joseph “J.S.” Cullinan, who became a lifelong friend. Cullinan in 1902 founded the Texas Company (see Sour Lake produces Texaco).

Sharp and Hughes in 1907 drilled test wells at Goose Creek/ “When both wells had to be abandoned because of the hard rock encountered, the two men began to consider the possibility of developing a roller rock bit. It was eventually arranged for Hughes to proceed with the designing and construction of a bit, with capital provided equally by Sharp and Cullinan.

Rotary drilling bits shaped like fishtails became obsolete in 1909 when the two inventors introduced a dual-cone roller bit. They created a bit “designed to enable rotary drilling in harder, deeper formations than was possible with earlier fishtail bits,” according to a Hughes historian. Secret tests took place on a drilling rig at Goose Creek, south of Houston.

Hard Rock at Goose Creek

“In the early morning hours of June 1, 1909, Howard Hughes Sr. packed a secret invention into the trunk of his car and drove off into the Texas plains,” noted Gwen Wright of History Detectives in 2006. The drilling site was near Galveston Bay. Rotary drilling “fishtail ” bits of the time were “nearly worthless when they hit hard rock.”

The new technology would soon bring faster and deeper drilling worldwide, helping to find previously unreachable oil and natural gas reserves. The dual-cone bit also created many Texas millionaires, explained Don Clutterbuck, one of the PBS show’s sources.

“When the Hughes twin-cones hit hard rock, they kept turning, their dozens of sharp teeth (166 on each cone) grinding through the hard stone,” he added.

Although several inventors tried to develop better rotary drill bit technologies, Sharp-Hughes Tool Company was the first to bring it to American oilfields. Drilling times fell dramatically, saving petroleum companies huge amounts of money.

Howard Hughes Sr. (1869 – 1924) on August 10, 1909, was awarded a U.S. patent for a dual-cone drill bit that could crush hard rock.

The Society of Petroleum Engineers has noted that about the same time Hughes developed his bit, Granville A. Humason of Shreveport, Louisiana, patented the first cross-roller rock bit, the forerunner of the Reed cross-roller bit.

Biographers have noted that Hughes met Granville Humason in a Shreveport bar, where Humason sold his roller bit rights to Hughes for $150. The University of Texas Center for American History Collection includes a 1951 recording of Humason talking about that chance meeting. He recalled spending $50 of his sale proceeds at the bar that evening.

After Walter Sharp died in 1912, his widow Estelle Sharp sold her 50 percent share in the company to Hughes. It became Hughes Tool in 1915. Despite legal action between Hughes Tool and the Reed Roller Bit Company in the late 1920s, Hughes prevailed and his oilfield service company prospered.

Hughes Tool

By 1934, Hughes Tool engineers designed and patented the three-cone roller bit, an enduring design that remains much the same today. Hughes’ exclusive patent lasted until 1951, which allowed his Texas company to grow worldwide. More innovations (and mergers) would follow.

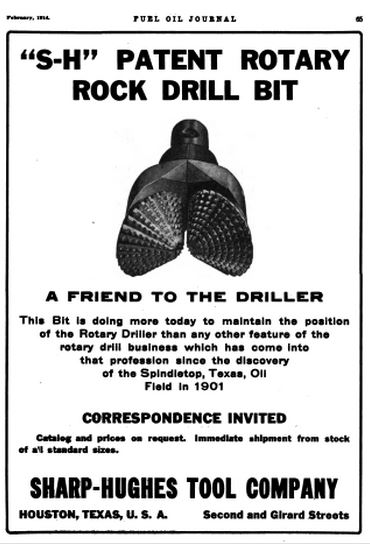

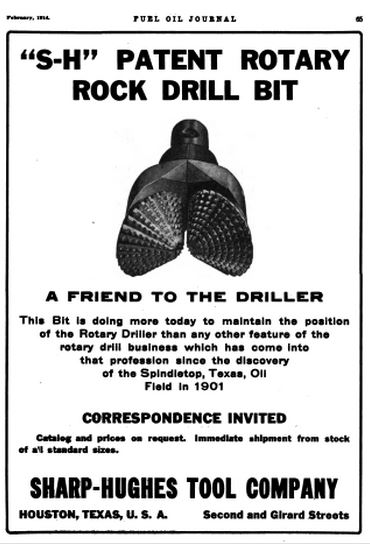

A February 1914 advertisement for the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company in Fuel Oil Journal.

Frank Christensen and George Christensen had developed the earliest diamond bit in 1941 and introduced diamond bits to oilfields in 1946, beginning with the Rangley field of Colorado. The long-lasting tungsten carbide tooth came into use in the early 1950s.

After Baker International acquired Hughes Tool Company in 1987, Baker Hughes acquired the Eastman Christensen Company three years later. Eastman was a world leader in directional drilling.

When Howard Hughes Sr. died in 1924, he left three-quarters of his company to Howard Hughes Jr., then a student at Rice University. The younger Hughes added to the success of Hughes Tool while becoming one of the richest men in the world. His many legacies include founding Hughes Aircraft Company and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Learn more in Making Hole – Drilling Technology.

Oilfield Service Competition

A major competitor for any energy service company, today’s Schlumberger Limited can trace its roots to Caen, France. In 1912, brothers Conrad and Marcel began making geophysical measurements that recorded a map of equipotential curves (similar to contour lines on a map). Using very basic equipment, their field experiments led to the invention of a downhole electronic “logging tool” in 1927.

After developing an electrical four-probe surface approach for mineral exploration, the brothers lowered another electric tool into a well. They recorded a single lateral-resistivity curve at fixed points in the well’s borehole and graphically plotted the results against depth – creating first electric well log of geologic formations.

Meanwhile, another service company in Oklahoma, the Reda Pump Company had been founded by Armais Arutunoff, a close friend of Frank Phillips. By 1938, an estimated two percent of all the oil produced in the United States with artificial lift, was lifted by an Arutunoff pump.

Learn more in Inventing the Electric Submersible Pump (also see All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2007); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Carl Baker and Howard Hughes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/carl-baker-howard-hughes. Last Updated: July 17, 2025. Original Published Date: December 17, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Jul 12, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

A simple forum for sharing ideas and research — and preserving history.

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) established this oil history forum page to help share research. For oilfield-related family heirlooms, the society also maintains an Oil & Gas Families page to locate suitable museum collections for preserving these unique histories. Information about old petroleum company stock certificates can be found at the popular forum linked to Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

Our forum below offers a simple way to share personal or academic research, subject ideas, comments, and other details about petroleum history. You can email the society at bawells@aoghs.org if you would like your research question posted. Please use the comment section at the bottom of this page to answer or make suggestions!

Research Request: July 9, 2025

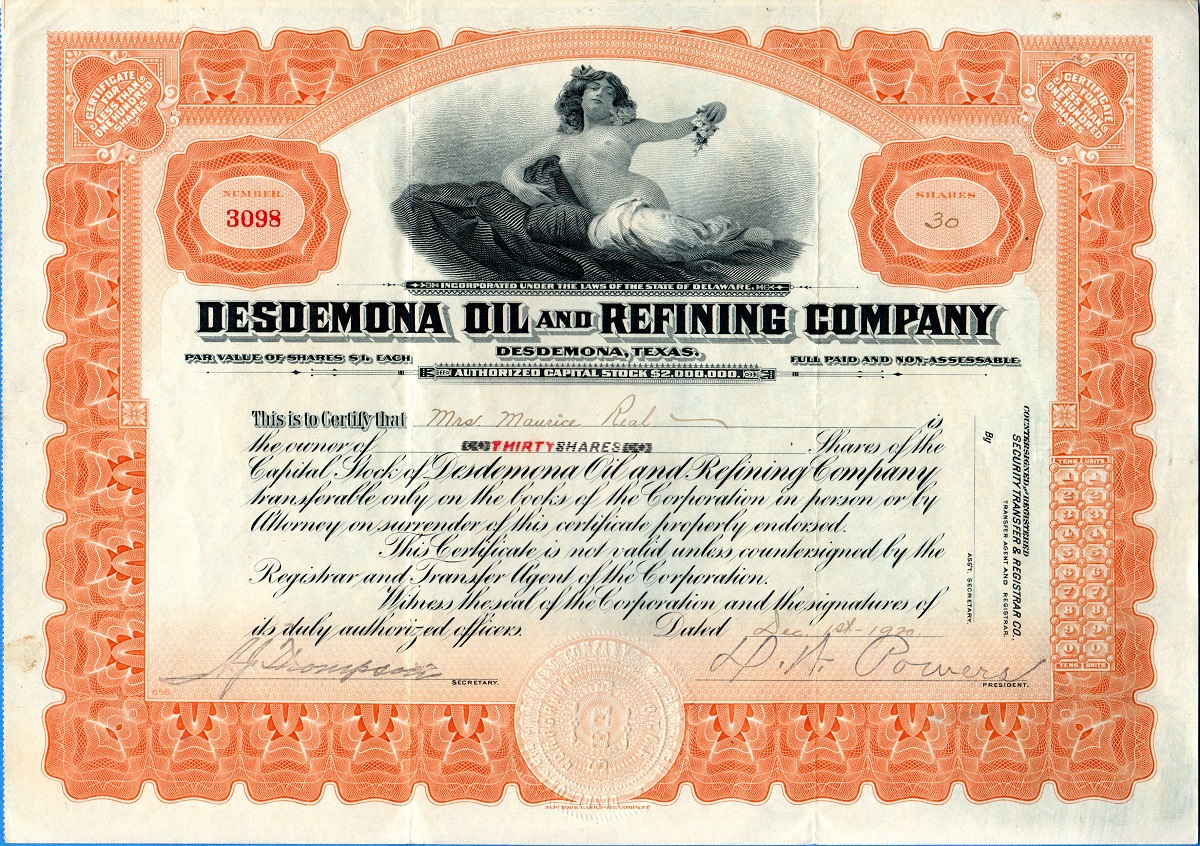

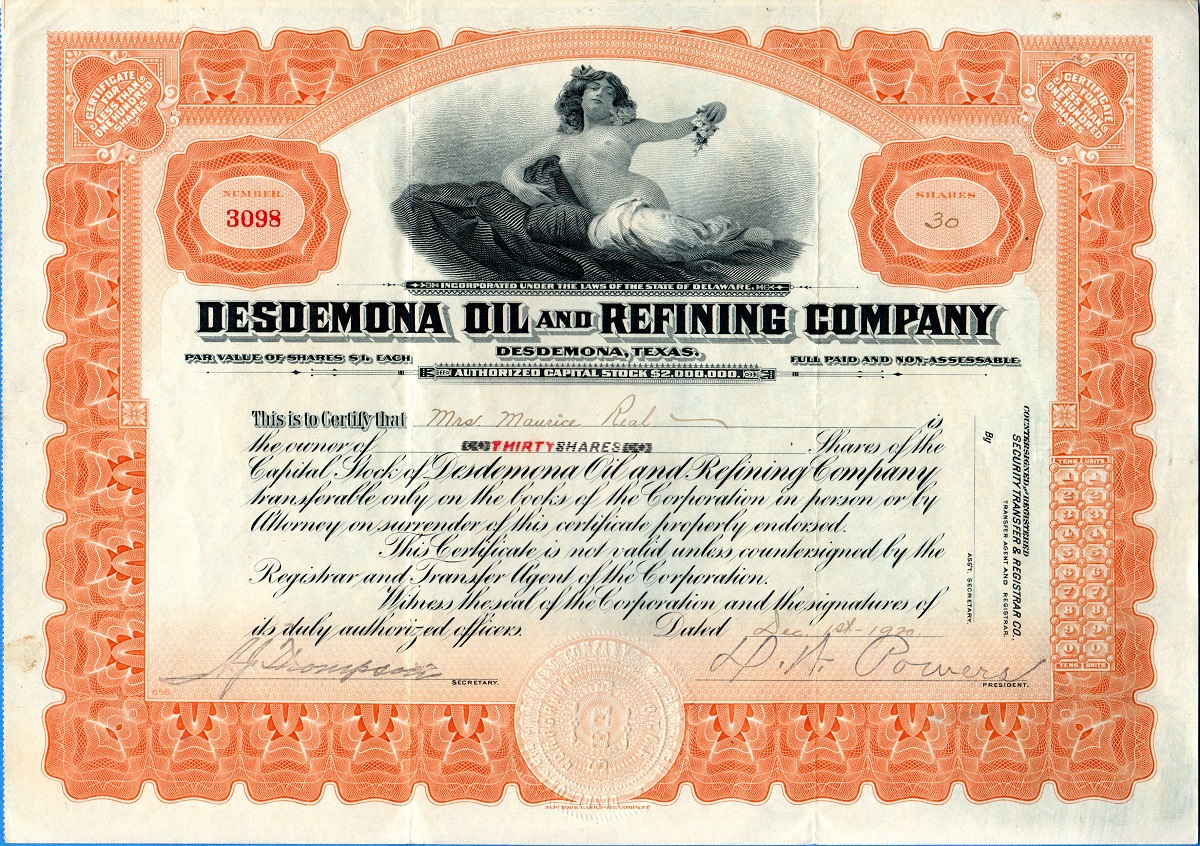

Desdemona Oil & Refining Company

Editor for International Bond and Share Society seeks source material for circa 1920 Texas company established during the North Texas drilling booms at Electra (1911), Ranger (1917), and Burkburnett (1918).

I’ve been subscribing for a few months and want to thank you for revealing so many obscure technologies and historical artifacts. I collect vintage stocks and bonds (all businesses, not just oil) and have always found it difficult to research these often obscure gas and oil companies. So far, I’ve not been successful in linking a certificate to any of the outfits you’ve mentioned, but it’s just a matter of time.

I recently wrote an article on the Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Co. that was published in the magazine I edit for the International Bond and Share Society, Scripophily. A stock I’ve been trying to research — without much luck — is the Desdemona Oil & Refining Company. If your members have any source material on this outfit, I’d be grateful.

Keep up the good work. — Max Hensley

Please post your reply in the comments section below or email maxdhensley@yahoo.com

Research Request: April 4, 2025

Standard Oil Public Relations Movie

Looking into 1947 film “A Farm In The Valley.”

Hello. My name is Carrie. My family is looking for a film that Standard Oil Company made in Virginia in 1947. It was titled “A Farm In The Valley.” I have several news articles but am looking for the film and/or any information that may be out there as part of the film was filmed on our farm (owned by the Rosen family at the time). I am hoping that maybe your group may have information or contact information for someone who may have information!

— Carrie

Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org

Research Request: November 14, 2024

Looking for The Gargoyle of Mobiloil

Pennsylvania researcher seeks a 1920s company magazine featuring her grandfather, “The Mobiloil King.”

I am in search of a copy of The Gargoyle magazine published by the Vacuum Oil Company from 1923. My great-grandfather, William I. Schreck was proprietor of the Keystone Service Station in Sayre, Pennsylvania, in the 1920’s and was locally dubbed “The Mobiloil King.”

I found an article on Newspapers.com — September 15, 1923 issue of the Sayre Evening Times, which states he was featured in The Gargoyle magazine, with two photos of his service station and an article written by him. I’m guessing it’s maybe the August 1923 or September 1923 issue. Any help locating this would be appreciated!

— Raquel

Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org

Research Request: November 8, 2024

Early Oilfield Production Technology

Artist seeks jerker/shackles for 2026 exhibition.

I am interested in the jerker/shackle lines used in early oil production for an exhibition I am planning for 2026. Does this oilfield equipment (entire assemblies or parts) ever come up for sale or auction? Perhaps there are private collectors or oil museums that might be interested in renting or lending some temporarily?

Best,

Aislinn

Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org (also see Eccentric Wheels and Jerk Lines).

Research Request: October 7, 2024

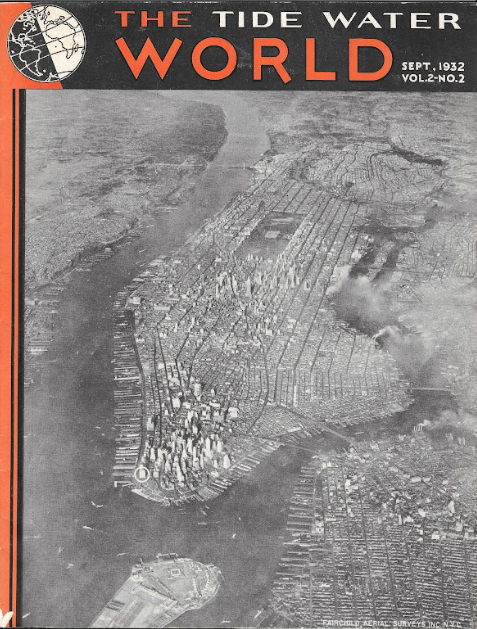

Researching Tidewater Oil Company

Researcher from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, seeks more about 1930s publication.

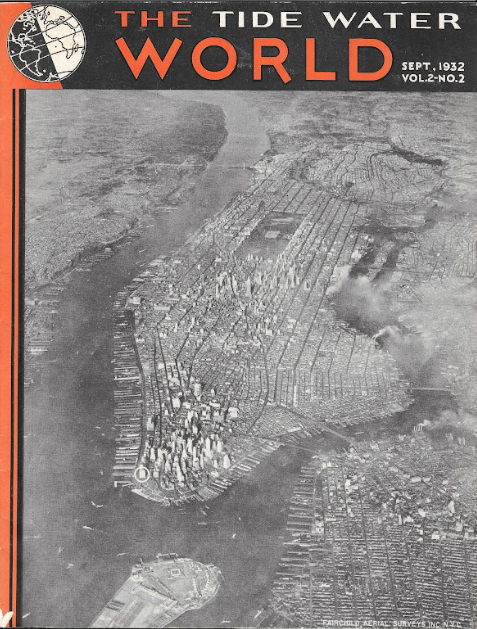

Hello: My grandfather authored an article in “The Tidewater World” in September 1932 (Vol. 2, No. 2). I have one complete issue. He worked in the Research and Development area of Tidewater Oil in Bayonne, New Jersey, 1928-1933.

Founded in 1887 in New York City, Tidewater Oil Company became a major refiner that sold its Tydol brand petroleum products on the U.S. East Coast. Photo courtesy Mark O’Neill.

I am looking for archives who may have additional issues in the series or who has a research focus on Tidewater Oil. Thank you.

— Mark O’Neill

Please call Mark at (717) 803-9918 or post reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: April 20, 2024

Wayne Canada Gasoline Pump

Preserving a rare 1930s Wayne Canada pump.

I recently saved an uncommon Wayne 50A “showcase” gas pump from a metal recycling facility here in Canada. I didn’t have much time for details as it was literally standing in the scrap yard beside the metal chipping machine. I paid the asking price and loaded it into my truck.

Upon arriving home I noticed that the I.D tag was a Wayne Canada, which was a surprise because the odds of it being a Canadian Showcase pump are significantly smaller than American as Canada had far fewer of the 50 and 50A pumps for obvious reasons. The I.D tag got me curious however, as it is stamped 1001-CJXA.

Canadian researcher seeks information about a rare 1930s Wayne Company pump 1001-CJXA.

Is there any way to determine which company ordered this exact gas pump? Is it true that the “1001” number would indicate that this is serial number 1 in Canada for this gas pump? I was told once that Wayne pumps in the 1930s began with the number 100 meaning 100.1 would be serial number 1. I’m not sure if that’s true.

Thanks very much for any help. I’m aware of the pumps rarity and historical significance, hence why I’m trying to find more information on it. Have a great day.

— Jonathan Rempel

Note: The Wayne Oil Tank and Pump Company of Ft. Wayne, Indiana, in 1892 manufactured a hand-cranked kerosene dispenser later converted for gasoline (see Wayne’s Self-Measuring Pump). Primarily Petroleum (oldgas.com) includes research posts with service station histories and gas pump collections; other resources include community oil and gas museums and the Canadian oil patch historians at the Petroleum History Society (PHS).

Please email jrrempel123@gmail.com or post reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: April 20, 2024

Name of Offshore Drilling Rig

Seeking the name of ODECO platform from 1970s.

I’m doing research on my late father, James R. Reese Sr., who worked in the Gulf of Mexico in the early 1970s and into the 1980s, and I’m trying to find the name of a rig he worked on for ODECO. We believe it may have been called the Ocean Endeavour, and we have a photo from my father’s 10th anniversary at the company with “Odeco 7” written on the back. My research points to the Endeavour, but I’m not confident of that. Has anyone heard of the platform and any other name it might have had?

Thank you for any help.

— James Reese Jr.

Note: ODECO (Ocean Drilling & Exploration Company) was founded in 1953. It was acquired by Diamond Offshore Drilling in 1992.

Please email tepapa@hotmail.com or post reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: March 29, 2024

Eastern Oklahoma History

Writer looking to connect petroleum exploration and railroad growth.

I’m writing a memoir that touches on Oklahoma, where I’m from originally, and I would like to learn more about what role did oil and gas exploration played in the expansion of the railroads into the Cherokee Nation in eastern Oklahoma in the late 1800s.

— Dave

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Request: February 22, 2024

Threatt Filling Station on Route 66

Architectural history of potential National Historic Landmark.

Established in the early 1920s, the Threatt Filling Station in Luther, Oklahoma, is considered the first – and potentially only – African American owned and operated gas station on Route 66. I am under contract with the National Park Service to perform a study to determine whether the the station is eligible to become a National Historic Landmark.

Constructed circa 1915 in Luther, Oklahoma, by Allen Threatt Sr., the Threatt Filling Station sold Conoco products for at least a portion of its many decades of service life, according to the Threatt Filling Station Foundation. Photo courtesy threattfillingstation.org.

What I am looking for is an Oklahoma contact, who has knowledge of the history of gas-oil distribution in the Sooner State in the 1920s-40s period. It appears that at one point, the Threatts were associated with Conoco. I would like to better understand how those supply-branding operations worked and whether there is historical paperwork that would cover this station.

Any assistance will be appreciated. Thank you,

— John

Please email john@archhistoryservices.com or post reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: January 2, 2024

Oil Refinery and R.R. Trackside Building Photos

Model railroader seeks detailed images of facilities in Santa Fe Springs and Los Angeles.

Thank you for sharing most interesting and valuable information. I use your society to help me with prototype research for my model railroading.

I am looking for information on the Powerine Oil Refinery at Santa Fe Springs circa 1950s and the trackside Hydril Oil Field Equipment buildings on approach to Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal, and photos and dimensions of buildings/building interiors for model railroading purposes.

A model railroad scene of the southern California petroleum industry in the 1950s includes oil derricks, “each with an operating horsehead style oil pump underneath.”

Justin Mitchell has recreated trackside oilfield derricks at Santa Fe Springs and researched oilfield engine audio files, “so I can add sound to the layout to match the operating pumps.”

The Powerine Oil Refinery at Santa Fe Springs closed in 1995. Skilled model railroaders prize detail and historical accuracy.

Best regards from Sydney, Australia

— Justin Mitchell

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Request: December 26, 2023

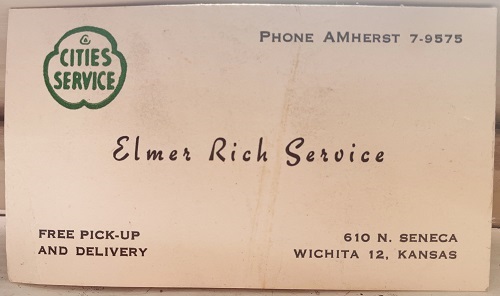

Cities Service in Wichita

Seeking service station photos.

I am looking for photographs of a Cities Service Station located at 610 N. Seneca Street in Wichita, Kansas, in the 1950s, maybe early 60s. I have my father’s business card from that station. I remember the service station even though I was only 4 years old. Any assistance is greatly appreciated.

— Pamela

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Request: September 25, 2023

Circa 1930 Driller from Netherlands

From a researcher investigating a great-great uncle’s role in the Texas oil patch.

A family history researcher in the Netherlands seeks help adding to her limited information about a great-great uncle who worked for J. Barry Fuel Oil Company in Texas oilfields from the 1920s to the early 1930s. The petroleum-related career of Ralph “Dutch” Weges included traveling on an early oil tanker later sunk during World War I.

Learn more and share research in Driller from Netherlands.

Research Request: July 13, 2023

How and Where Standard Oil produced Naphtha

From a writer working on a history of the lighting of New York City.

In the late 19th century, Standard Oil gained control of all of the gas lighting companies in New York. My understanding is that they did so in part because the gas companies at the time produced something called water gas, which relied on the use of naphtha, and Standard Oil produced almost all of the naphtha in the United States.

How and where Standard Oil produced its naphtha around 1890-1900 and how it would have transported it to the NYC gas companies? Would it have been produced in the Midwest and shipped east by pipeline? Railcar? Did they ship crude oil east and refine it into naphtha somewhere on the East Coast?

Also, any suggestions for where I could find info on how much naphtha Standard Oil produced around that time and, perhaps, how much of it was shipped to New York? I have looked in all the standard histories and tried every Google and newspaper searches. Can anyone offer suggestions? Thanks very much.

— Mark

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Reply

August 26, 2023, from Reference Services, American Heritage Center

The American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming does hold a set of records for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, 1874-1979. The online guide is posted here. This is one of our older guides not yet converted to the online format, and it includes many handwritten notes about the removal of items from this manuscript collection to other collections.

— American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

Research Request: June 23, 2023

Houston Petrol Filler

From an Australian “petrol bowser” researcher

I recently came across this brass fitting which is clearly marked THE HOUSTON PETROL FILLER Pat 1307. The patent number is extremely early. I am assuming it is part of an early petrol pump or as we call them here in Australia, a petrol bowser. Is there any chance anyone can identify what this was originally part of. Many thanks for your help. Regards.

— Justin

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Reply

October 18, 2023 (also from Australia)

Hello Justin,

I have one of these that has turned up in my late father’s stuff. Identical to yours except for the screwed end which has a strangely shaped protrusion. I’ll send you a pic if you are interested. Did you ever find out anything about it? I’m looking for somewhere to donate it — where it will be appreciated.

Regards, David

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Request: April 12, 2023

Information about Wooden Barrel

From researcher who has a barrel with a red star and

I have got this old oil barrel. I’m trying to find out more information about it. I’m guessing around the 1920’s but I really have no clue. I was hoping someone there could shed some light on it. I’m not interested in selling it just some information. Much appreciated!

— Robert

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Reply

November 25, 2023

To Robert,

Your wood barrel is clearly “The Texas Company” (i.e., Texaco) container for “Petroleum Products.” Except for the red star with big green T, the rest of the lithography on your barrel is harder to interpret. My source for reference is Elton N. Gish’s self-published 2003 book Texaco’s Port Arthur Works. Unfortunately, the book does not have an index, but it has a lot of company photographs in it surrounded by narratives. Most of the photos of product containers are for metal cans and drums, but one group photo of a product display dated 1932 shows wood barrels still in use although metal drums predominate by that time. The only wood barrels discussed by Gish are for “slack barrels” used for asphalt, and it looks like you have some asphalt residue on your barrel top. Gish indicates that the “Red star-green T” trademark lithography began to be used by 1909 and continued to be used to present in various renditions, but a 1920s date range for you barrel seems reasonable. I hope this helps.

— Andy

Research Request: September 3, 2022

Identifying a Circa 1915 Gas Pump

From the lead mechanic at San Diego Air & Space Museum

I’m hoping someone visiting the American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s website can help me identify the gas pump we are restoring here at the San Diego Air and Space Museum. I believe it’s a Gilbert and Barker from 1915 or so.

The data plate is missing and I’ve been having trouble finding a similar one in my online search. Thanks!

— Gary Schulte, Lead Mechanic, SDASM

Please email Gary engshop@sdasm.org or post your reply in the comments section below.

Learn more history about early kerosene and gasoline pumps in First Gas Pump and Service Station; a collector’s rare 1892 pump in Wayne’s Self-Measuring Pump; and the 24-hour Gas-O-Mat in Coin-Operated Gas Pumps.

Research Request: August 11, 2022

Gas Streetlights in the Deep South

From a professor, author and “history detective”

I am doing historical research on gas streetlights in the Deep South. Any suggestions will be much appreciated. My big problem at the moment is Henry Pardin. He bought the patent rights to a washing machine in Washington, DC, in 1856 and was in Augusta, Georgia, in 1856. Pardin set up gas streetlights in Baton Rouge, Holly Springs, Natchez, and Shreveport in 1857-1860. I have failed to find him in any of the standard research sources.

Any help on gas street lights in the south before the Civil War is appreciated. Thank you for your time.

— Prof. Robert S. “Bob” Davis, Blountsville, Alabama, Genws@hiwaay.net

Please email Bob or post your reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: August 5, 2022

Drop in Stop Action Film

From a stop action film researcher:

“Your website is doing good things for education. It is a gold mine for STEM high school teachers — and also for people like me, who like stop motion oil industry films, Bill Rodebaugh noted in an August 2022 email to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

Researcher seeks the origin of stop action film (oil?) drops.

Rodebaugh, who has researched many stop motion archives (including AOGHS links at Petroleum History Videos), seeks help finding the source of an unusual character — a possible oil drop with a face and arms. The purpose of the figures remains unknown.

“I am discouraged about finding that stop motion film, because I have seen or skimmed through many of those industry films, which are primarily live action,” Rodebaugh explained. He knows the puppet character is not from the Shell Oil educational films, “Birth of an Oil Field” (1949) or “Prospecting for Petroleum” (1956). He hopes a website visitor can assist in identifying the origin of the hand-manipulated drops. “I am convinced that if this stop motion film can be found, it would be very interesting.”

— Bill Rodebaugh, brodebaugh@suddenlink.net

Please email Bill or post your reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: July 2022

Gas Station Marketplace History

From an automotive technology writer:

I’m looking for any information on the financial environment during the early days of the automotive and gasoline station industry. The idea is to compare and contrast the market-driven forces back then to the potential for government subsidies/investments etc. to pay for electric vehicle charging stations today.

At this point, I have not found any evidence but I wanted to be thorough and ask the petroleum history community. From what I have seen, gas stations were funded privately by petroleum companies and their investors and shareholders.

I’m not talking about gas station design or the impact on the nation/communities, but the market forces behind the growth of the industry. Please let me know of any recommended sources. I have already read The Gas Station in America by Jackie & Sculle.

— Gary Wollenhaupt, gary@garywrites.com

Please email Gary or post your reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: April 2022

Seeking Information about Doodlebugs

From a Colorado author, consulting geologist and engineer:

I am trying to gather information on doodlebugs, by which I mean pseudo-geophysical oil-finding devices. These could be anything from modified dowsing rods or pendulums to the mysterious black boxes. Although literally hundreds of these were used to search for oil in the 20th century, they seem to have almost all disappeared, presumably thrown out with the trash. If anyone has access to one of these devices, I would like to know.

— Dan Plazak

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org. Dan Plazak is a longtime AOGHS supporting member and a contributor to the historical society’s article Luling Oil Museum and Crudoleum.

Research Request: February 2022

Know anything about W.L. Nelson of University of Tulsa?

From an associate professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts:

I am doing research on the role of the University of Tulsa in the education of petroleum refining engineers and in particular am seeking information about a professor who taught there named W.L. Nelson, author of the textbook Petroleum Refinery Engineering, first published in 1936. He taught at Tulsa until at least the early 1960s. He was also one of the founders of the Oil and Gas Journal and author of the magazine’s “Q&A on Technology” column. If anyone has any leads for original archival sources by or about Nelson and UT, I would appreciate hearing from you.

Thank you and best wishes, M.G.

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Emailed response to “Seeking Information about W.L. Nelson of University of Tulsa.”

My late father was a 1943 graduate of the University of Tulsa with a degree in petroleum engineering with an emphasis in refining. By the time my late uncle graduated in 1948, his degree had become chemical engineering with an emphasis in refining. Both had high regard for Wilbur L. Nelson. Both had long careers in the refining at Murphy Oil Corporation and Sun Oil Company. My father would pass along to me his obsolete Petroleum Refinery Engineering, as Nelson periodically updated his book. I will check my father’s papers for any Nelson relics. Let me know how your inquiry goes.

— Professional Engineer, El Dorado, Arkansas

————————

Oil History Forum

Research requests from 2021:

Star Oil Company Sign

Looking for information about an old porcelain sign from the Star Oil Company of Chicago.

Learn more in Seeking Star Oil Company.

Bowser Gas Pump Research

I have a BOWSER, pump #T25988; cut #103. This is a vintage hand crank unit. I can’t seem to find any info on it! Any help would be appreciated, Thank You. (Post comments below) — Larry

Hand-cranked Bowser Cut 103 Pump.

Originally designed to safely dispense kerosene as well as “burning fluid, and the light combustible products of petroleum,” early S.F. Bowser pumps added a hose attachment for dispensing gasoline directly into automobile fuel tanks by 1905. See First Gas Pump and Service Station for more about these pumps and details about Bowser’s innovations.

Bowser company once proclaimed its “Cut 103” as “the fastest indoor gasoline gallon pump ever made” with an optional “hose and portable muzzle for filling automobiles.”

Collectors’ sites like Oldgas.com offer research tips for those who share an interest in gas station technological innovations.

Circa 1900 California Oilfield Photo

My grandfather worked the oilfields in California in the early 1900’s.

He worked quite a bit in Coalinga and also Huntington Beach. He had this in his old pictures. I would like to identify it if possible. The only clue that I see is the word Westlake at the bottom of the picture. What little research I could do led me to believe it might be the Los Angeles area?

I would appreciate any help you can provide. (Post comments below.) — B.

Cities Service Bowling Teams and Oil History

I was wondering if there are any records or pictures of bowling leagues and teams for Cities Service in the late 1950s and early 1960s in Houston, Texas, or Lafayette, Louisiana. I would appreciate any information. My dad was on the team. (Post comments below.) — Lisa

Oilfield Storage Tanks

My family has a farm in western PA and once had a small oil pump on the land. I’m trying to learn how the oil was transported from the pump. I know a man came in a truck more than once each week to turn on the pump and collect oil, but I don’t know if there was a holding tank, how he filled his truck, etc. (My mother was a child there in the ’40s and simply can’t recall how it all worked.) Can anyone point me at a resource that would explain such things? I’m working on a children’s book and need to get it right. Thank you. — (Post comments below.) Lauren

Author seeking Historical Oil Prices

Can anyone at AOGHS tell me what the ballpark figures are in the amount of petroleum products so far extracted, versus how much oil-gas is left in the world? Also: the price per barrel of oil every decade from the 1920s to the present. And the resulting price per gallon during the decades from 1920 to the present year? I have almost completed my book about an independent oilman. Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

— John

Painting related to Standard Oil History

I am researching an old oil painting on canvas that appears to be a gift to Esso Standard Corp. Subject: Iris flowers. There is some damage due to age but it is quite interesting. The painting appears to be signed in upper right corner: Hirase?

On the back, along each side, is Japanese writing that I think translates to “Congratulations Esso Standard” and “the Tucker Corporation” or “the Naniwa Tanker Corporation.” Date unknown, possibly 1920s.

I am not an expert in art nor Japanese culture, so some of my translation could be incorrect. I was hoping you or your colleagues might shed some light on this painting.

— Nancy

Please post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Early Gasoline Pumps

For the smaller, early stations from around 1930, was the gas stored in a tank in the ground below the dispenser/pump? — Chris Please ad comment below.

Oilfield Jet Engines

I was wondering about a neat aspect of oil and natural gas production; namely, the use of old, retired aircraft jet engines to produce power at remote oil company locations, and to pump gas/liquid over long distances in pipelines. Does anyone happen to recall what year a jet engine was first employed by the industry for this purpose? Nowadays, there is an interesting company called S&S Turbine Services Ltd. (based at Fort St. John, British Columbia) that handles all aspects of maintenance, overhaul and rebuilding for these industrial jets.

— Lindsey

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Natalie O. Warren Propane Tanker Memorabilia

My father spent his working life with Lone Star Gas, he is gone many years now I am getting on. Going through a few of his things. A little book made up that he received when he and my mother attended the commissioning of the Natalie O. Warren Propane Tanker. I am wondering if it is of any value to anyone. Or any museum.

— Bill

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Elephant Advertising of Skelly Oil

My grandfather owned a Skelly service station in Sidney, Iowa in the 1930s and 1940s. I have a photo of him with an elephant in front of the station. I recall reading somewhere that Skelly had this elephant touring from station to station as an advertising stunt. Does anyone have any more history on the live elephant tour for Skelly Oil? I’d love to find out more. — Jeff Please ad comment below.

Tree Stumps as Oilfield Tools

I am a graduate student at the Architectural Association in London working on a project that looks at the potential use of tree stumps as structural foundations. While researching I found the following extract from an article on The Petroleum Industry of the Gulf Coast Salt Dome Area in the early 20th century: “In the dense tangle of the cypress swamp, the crew have to carry their equipment and cut a trail as they go. Often they use a tree stump as solid support on which they set up their instruments.” I have been struggling to find any photos or drawings of how this system would have worked (i.e. how the instruments were supported by the stump) I was wondering if you might know where I could find any more information?

— Andrew

Post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Texas Road Oil Patch Trip

“Hi, next year we are planning a road trip in the United States that starts in Dallas, Texas, heading to Amarillo and then on to New Mexico and beyond. We will be following the U.S. 287 most of the way to Amarillo and would like to know of any oil fields we could visit or simply photograph on the way. From Amarillo we plan to take the U.S. 87. We realise this is quite a trivial request but you help would be much appreciated.”

— Kristin

Please post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Antique Calculator: The Slide Rule

Here’s a question about those analog calculating devices that became obsolete when electronic pocket calculators arrived in the early 1970s…Learn more in Refinery Supply Company Slide Rule.

Please post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

—————

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. Contact the society at bawells@aoghs.org if you would like a research question added. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

.

by Bruce Wells | May 21, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

Marketing icon “Dino” and friends introduced children to wonders of the Mesozoic era courtesy of Sinclair Oil.

Harry Ford Sinclair established his petroleum company in 1916, making it one of the oldest continuous names in the U.S. energy industry. Appearing among other Sinclair Oil Company dinosaurs during the 1933-1934 World’s Fair in Chicago, “Dino” became a marketing icon whose popularity with children remains today. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | May 19, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

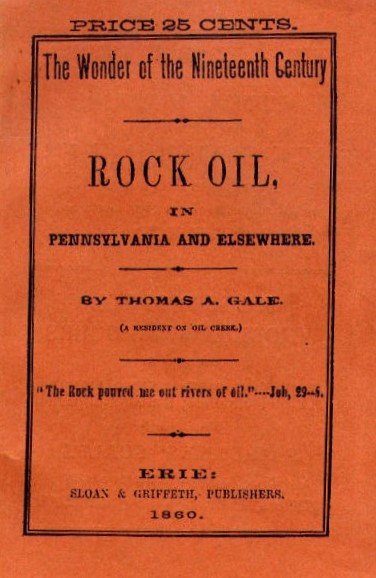

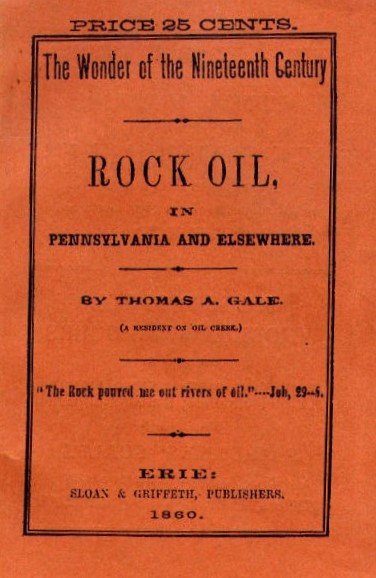

Less than 10 months after Edwin L. Drake and his driller William “Uncle Billy” Smith completed the first commercial U.S. oil well on August 27, 1859, along Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, Thomas A. Gale wrote a detailed study about rock oil — and helped launch the petroleum age.

Published in 1860, The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere described a radical fuel source for the popular lamp fuel kerosene, which had been made from coal for more than a decade.

“Those who have not seen it burn may rest assured its light is no moonshine; but something nearer the clear, strong, brilliant light of day,” Gale declared in his 25-cent pamphlet printed in Erie by Sloan & Griffith Company.

Thomas Gale’s 80-page pamphlet in 1860 marked the beginning of the petroleum age, illuminated with kerosene lamps.

“In other words, rock oil emits a dainty light; the brightest and yet the cheapest in the world; a light fit for Kings and Royalists, and not unsuitable for Republicans and Democrats,” Gale added.

Oil in Rocks

Gale’s descriptions of the value of petroleum helped launch investments in new exploration companies, especially as he noted the commercial qualities of Pennsylvania oil for refining into kerosene, the distilled “coal oil” invented in 1848 by Canadian chemist Abraham Gesner.

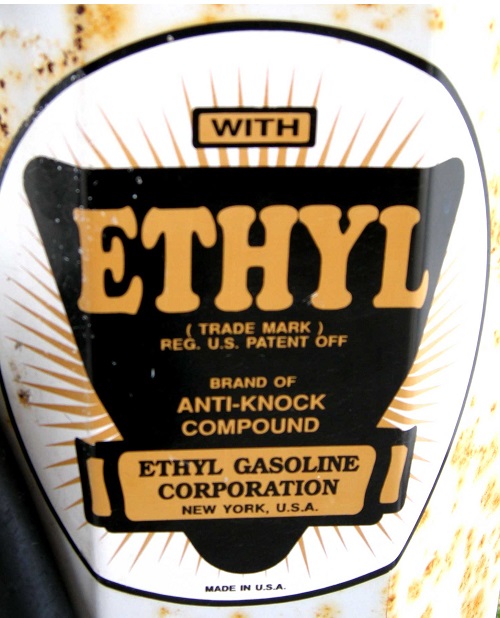

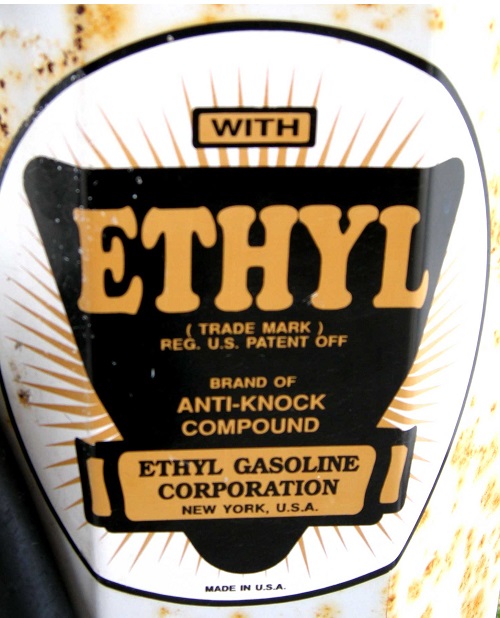

Historians regard the 80-page publication as the first book about America’s petroleum industry. The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere was almost forgotten until 1952, when the Ethyl Corporation of New York republished the work. Only three original copies were known to exist.

“Not by the widest stretch of the imagination could Thomas Gale have realized, when he put down his pen on June 1, 1860, that he had written a book destined to become one of the rarest of all oil books,” proclaimed the Ethyl historian when the company republished Gale’s book.

Ethyl Corporation noted the scarcity of copies of the book had prevented “all but a few historians” from giving the book the attention it deserved.

“Gale wrote his book to satisfy a public desire for more information about petroleum. Newspapers had carried belated accounts of Drake’s discovery well, and the mad scramble for oil that followed, but actually the world knew little about petroleum.”

“The Rock poured…”

The book’s 11 chapters explain practical aspects of the new petroleum industry. Chapters one and two, “What is Rock Oil?” and “Where is the Rock Oil found?” were followed by “Geological Structure of the Oil Region.”

Chapters four through six explained the early technologies (and costs) for pumping the oil, while the next two chapters examine “Uses of Rock Oil.” The final three chapters offered “Sketches of several oil wells,” “History of the Rock Oil Enterprise,” and “Present condition and prospects of Rock Oil interests in different localities.”

Chapter three in The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere features the “geological structure of the oil region,” today part of Oil Creek State Park in northwestern Pennsylvania.

Originally published by Sloan & Griffith of Erie, Pennsylvania, the 1860 cover noted the author as “a resident of Oil Creek” and included a biblical quote, “The Rock poured me out rivers of oil,” from Job, 29:6.

In addition to mysteriously burning gasses and “tar pits,” explorers for millennia have referenced signs of coal, bitumen, and substances very much like petroleum — a word derived from the Latin roots of petra, meaning “rock” and oleum meaning “oil.”

But did Thomas Gayle’s 1860 work produce the first book about oil as Ethyl Corporation historians believed when the company reprinted it in 1952? In fact, there have been many references to natural oil seeps recorded millennia ago (including in the Bible), according to a geologist who has researched the earliest sightings of petroleum.

Illuminating Petroleum

Several years before the 1859 oil discovery in Pennsylvania, businessman George Bissell hired a prominent Yale chemist to study the potential of oil and its products to convince potential investors (see George Bissell’s Oil Seeps).

“Gentlemen, it appears to me that there is much ground for encouragement in the belief that your company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive processes, they may manufacture very valuable products,” reported Benjamin Silliman Jr. in 1855.

Silliman’s groundbreaking “Report on the Rock Oil, or Petroleum, from Venango Co., Pennsylvania, with Special Reference to its Use for Illumination and Other Purposes,” convinced the petroleum industry’s earliest investors to drill at Titusville. Cable-tool technology developed for brine wells would drill the well.

According to historian Paul H. Giddens in the 1939 classic, The Birth of the Oil Industry, Silliman’s 1855 report, “proved to be a turning-point in the establishment of the petroleum business, for it dispelled many doubts about its value.”

The Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company would evolve into the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut, which became America’s first oil company after Drake completed the first U.S. commercial well drilled seeking oil in 1859.

Rock Oil Products

In addition to providing oil for refining into kerosene lamps (and someday rockets), oilfield discoveries led to many products. Early petroleum products included axle greases, an oilfield paraffin balm, and in Easton, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons.

Further, oil offered an improved asphalt prior to the first U.S. auto show in November 1900 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

Ethyl Corporation was established in 1923 by General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey,

Responding to consumer demand for better automobile gasoline, General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey established the Ethyl Corporation in 1923. The company initially downplayed the danger of tetraethyl lead. Leaded gas would be banned for use in cars in the 1970s

Importantly, high-octane leaded aviation fuel proved vital for victory in World War II — and the additive still fuels many piston-engine aircraft and racecars.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere (1952); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1939); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Oil Book of 1860.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/first-oil-book-of-1860. Last Updated: May 17, 2025. Original Published Date: May 31, 2020.

by Bruce Wells | May 7, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

Erected for the 1953 International Expo, Tulsa’s towering roughneck grew into an Oklahoma landmark.

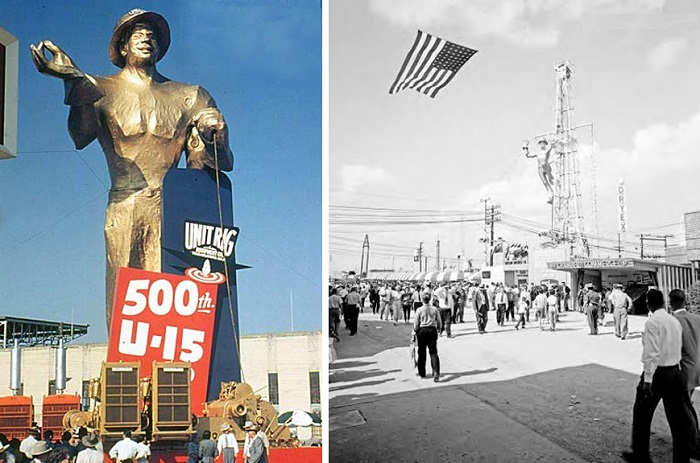

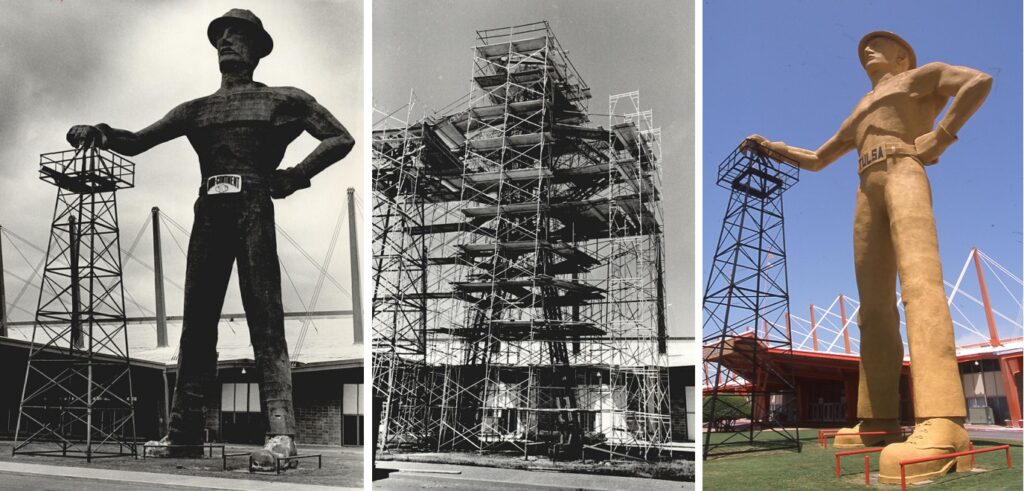

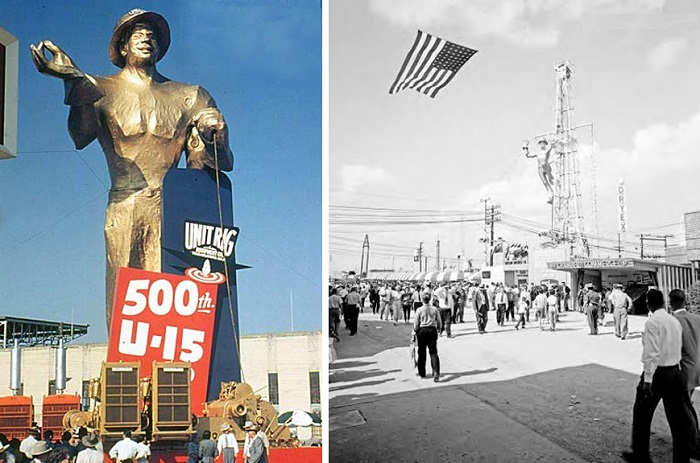

With an arm casually resting on a steel derrick, the 76-foot giant cannot be missed by visitors to the Tulsa County Fairgrounds. Popularly known as the “Golden Driller,” the first version of the 22-ton Oklahoma roughneck appeared in May 1953 as an oilfield supply company promotion during the Tulsa International Petroleum Exposition.

The leading oil and natural gas equipment expo, which began in 1923 as the International Petroleum Exposition and Congress, took place for decades at the Tulsa County Free Fair site. Tulsa independent producer William Skelly established the expo while he was serving as president of the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce.

In 1953, a golden “roustabout” statue conceived by the Mid-Continent Supply Company of Fort Worth, Texas, proved so popular it returned in 1959 after receiving a makeover.

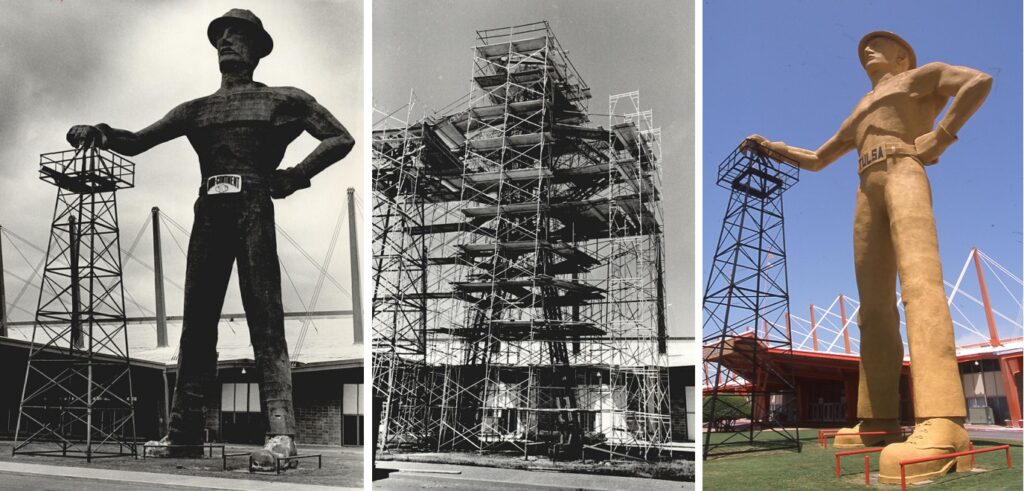

Designated an Oklahoma state monument in 1979, the Golden Driller was permanently installed for the 1966 International Petroleum Exposition in Tulsa. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Another refurbishment and then neglect followed the fortunes of the petroleum industry. But civic leaders now proclaim the the Tulsa driller the most photographed landmark in the city once known as the “Oil Capital of the World.”

Although Mid-Continent Supply’s smaller first statue of 1952 impressed expo visitors, it was the 1959 version with an oilfield worker climbing a derrick that led to Tula’s current Golden Driller. “This time he was much more chiseled and detailed and was placed climbing a derrick and waving,” explained a volunteer for the Tulsa Historical Society in 2010.

The original Golden Driller of 1953, left, proved so popular that a smaller, rig-climbing version (called The Roustabout) returned for the 1959 International Petroleum Exposition. The Tulsa fairgrounds opened in 1903. Images courtesy Tulsa Historical Society.

According to the society’s “Tulsa Gal,” the 1959 rig-climbing roustabout’s popularity inspired Mid-Continent Supply to donate it to the Tulsa County Fairgrounds Trust Authority when the international expo ended. Sometime during the next seven years, the giant was redesigned to better withstand the elements, she noted.

Taller and much stronger, the modern Golden Driller debuted in 1966 at Tulsa’s International Petroleum Exposition. The new look came from a Greek immigrant, George “Grecco” Hondronastas, an artist who had worked on the 1953 exposition’s hard-hatted statue.

According to writer Tony Beaulieu, Hondronastas was an eccentric and prolific artist who was proud of becoming a U.S. citizen through military service in World War I. He attended the Art Institute of Chicago and later became a professor. His design work included business promotions and parade floats.

Mid-Continent Supply Company constructed a permanent version in 1966 with steel rods to withstand up to 200 mph winds but more work would be needed. The giant was refurbished again in 1979, after it was designated an Oklahoma state monument.

Hondronastas came to Tulsa for the first time in 1953, “to help design and build an early version of the Golden Driller,” explained Beaulieu, who also noted the artist “fell in love with the city of Tulsa and later moved his wife and son from Chicago to a duplex near Riverview Elementary School, just south of downtown.”

The artist was immensely proud of designing the Golden Driller — “and he would tell that to anyone he met,” added his son Stamatis, quoted in Beaulieu’s 2014 article, “An Oil Town’s Golden Idol, “ in This Land magazine.

“The battered Golden Driller statue has been declared an official state monument,” noted the Daily Oklahoma more than a decade after Mid-Continent Supply donated its 1966 version to the Tulsa County Fairgrounds. Rebuilt in 1979 (center), the modern statue has was repainted in 2011. Photos courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

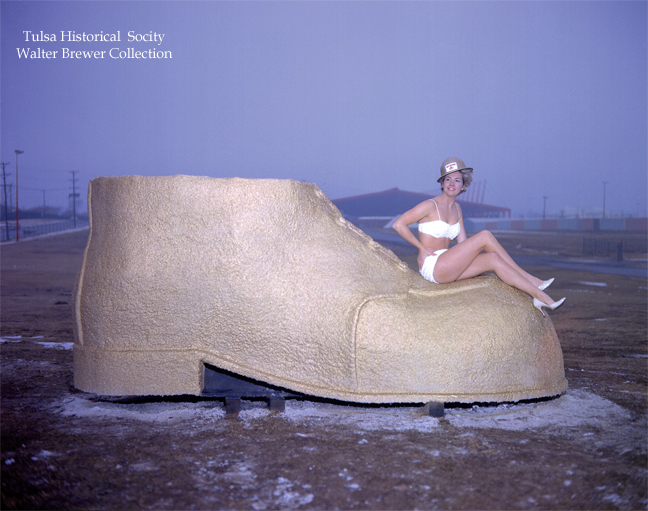

The late Tulsa photographer Walter Brewer documented construction of the giant with images later donated to the Tulsa Historical Society. Designated a state monument and refurbished again in 1979 (the year Hondronastas died), the statue as it appears today was permanently installed at East 21st Street and South Pittsburg Avenue.

The statue contains 2.5 miles of rods and mesh, along with tons of plaster and concrete. It can withstand up to 200 mph winds, “which is a good thing here in Oklahoma,” according to Tulsa Gal. It was painted it’s golden mustard shade in 2011,

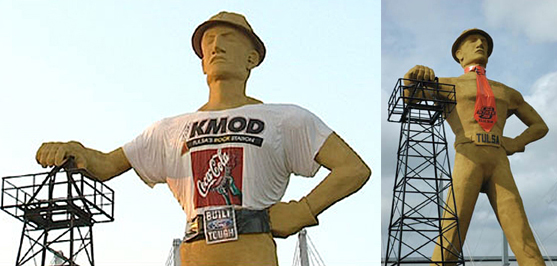

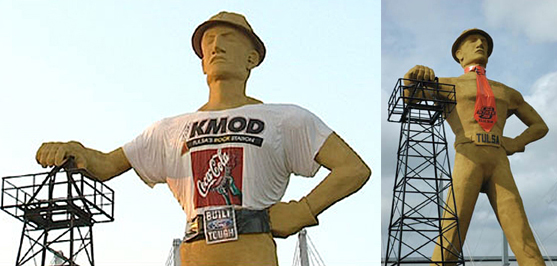

Tulsa’s giant driller has sported t-shirts, belts, beads, neckties and other promotions during state fairs. A Covid-19 mask was added in the summer of 2020. Images courtesy the Tulsa Historical Society.

The Golden Driller’s right hand rests on an old production derrick moved from oilfields near Seminole, Oklahoma — a town that has its own extensive petroleum heritage.

Fully refurbished in the late 1970s, the Golden Driller — by now a 43,500-pound tourist attraction — is the largest free-standing statue in the world, according to Tulsa city officials. “Over time the Driller has seen the good and the bad,” said Tulsa Girl.

“He has been vandalized, assaulted by shotgun blasts and severe weather,” she added. “But he has also had more photo sessions with tourists than any other Tulsa landmark and can boast of many who love him all around the world.”

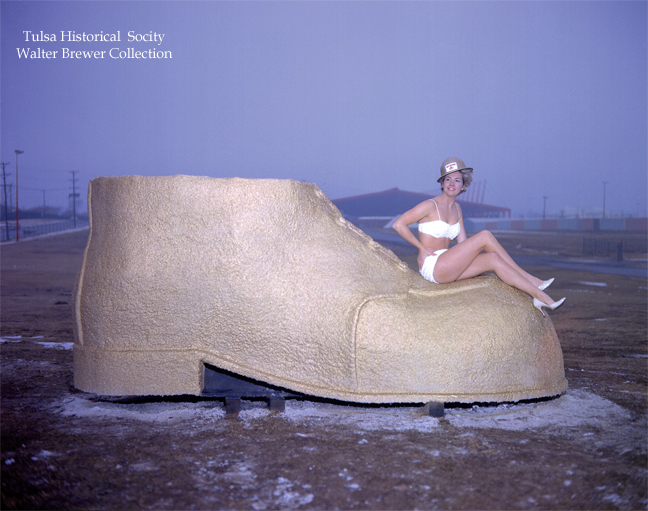

An unidentified model posed on one of the Golden Driller’s shoes, probably sometime during construction of the permanent version in time for the opening of Tulsa’s 1966 International Petroleum Exposition.

The Golden Driller, a symbol of the International Petroleum Exposition. Dedicated to the men of the petroleum industry who by their vision and daring have created from God’s abundance a better life for mankind. — Inscription on a plaque at the Golden Driller’s base.

An American Oil & Gas Historical Society 2007 Energy Education Conference and Field Trip in Oklahoma City included visits to oil museums in Seminole, Drumright and Tulsa — with a stop at the Golden Driller. Photo by Timothy G. Wells.

Although the first International Petroleum Exposition and Congress had no giant roughneck statue in 1923, the expo helped make Tulsa famous around the world. Leading oil and gas companies were attracted to Tulsa as early as 1901, six years before Oklahoma became a state (learn more in Red Fork Gusher).

An even bigger oilfield discovery arrived in 1905 on a farm south of the future oil capital. On November 22, 1905, the Ida Glenn No. 1 well erupted a geyser of oil southeast of Tulsa. The giant Glenn Pool field would forever change Tulsa and Oklahoma.

Learn more Tulsa history in the extensive collection of the Tulsa Historical Society.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Tulsa Oil Capital of the World, Images of America (2004); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America

(2004); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America (2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Golden Driller of Tulsa.” Authors: B.A. and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/golden-driller-tulsa. Last Updated: May 17, 2025. Original Published Date: March 1, 2006.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 17, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

Standard Oil curbed the excitement of unruly speculators trading oil and pipeline certificates.

In a sign of the growing power of John D. Rockefeller at the end of the 19th century, Standard Oil Company brought a decisive end to Pennsylvania’s highly speculative — and often confusing — trading markets at oil exchanges.

On January 23, 1895, the Standard Oil Company’s purchasing agency in Oil City, Pennsylvania, notified independent oil producers it would only buy their oil at a price “as high as the markets of the world will justify” and not necessarily “the price bid on the oil exchange for certificate oil.” The action would bring an end to the “paper oil” markets of brokers and buyers.

(more…)

(2007); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.