by Bruce Wells | Oct 10, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

After months of hard drilling, a North Texas oil well roared in at Ranger in 1917.

As World War I continued in Europe, the “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery well of October 1917 in Eastland County, Texas, revealed a giant oilfield that would help fuel the Allied victory.

Residents of the town of Ranger — about halfway between Dallas and Abilene — had been eager to find oil, especially after reading newspaper accounts of an oilfield discovery on April Fool’s Day 1911 at Electra in neighboring Wichita County. A decade earlier in southeastern Texas, the “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill had launched the modern U.S. petroleum industry.

Detail of a photo showing “Roaring Ranger,” the McCleskey No. 1 well, erupting oil in Eastland County and launching a North Texas drilling boom. Photo courtesy Ranger Historical Preservation Society.

As the area’s cotton farmers struggled with severe drought, Ranger town officials hoped to strike “black gold.” For help, they turned to William K. Gordon, vice president of the Texas and Pacific Coal Company in Thurber. His company mined shale from hills near Thurber.

“Roaring Ranger”

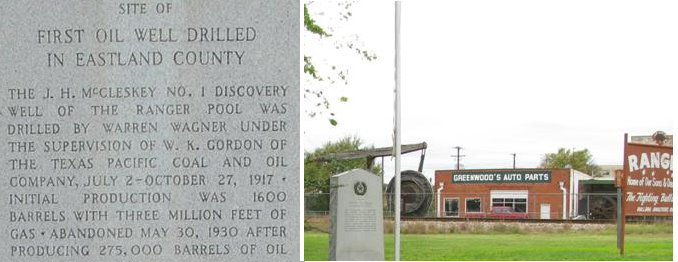

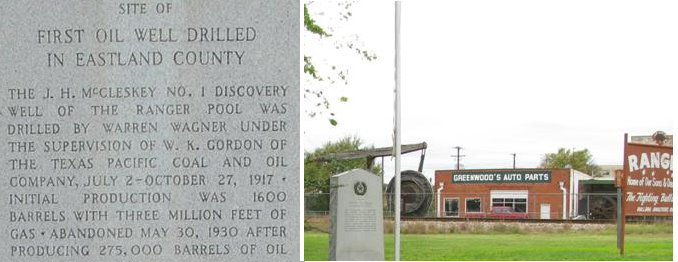

After one failed test with a shallow well, Gordon agreed to drill the second attempt up to 3,500 feet deep. Drilling with basic cable-tool technology, Gordon and contractor Warren Wagner spudded the exploratory wildcat well on July 2, 1917, on the McCleskey farm, two miles south of Ranger.

After more than three months of drilling, the J.H. McCleskey No. 1 well erupted a geyser of oil on October 17, 1917, from a depth of 3,432 feet.

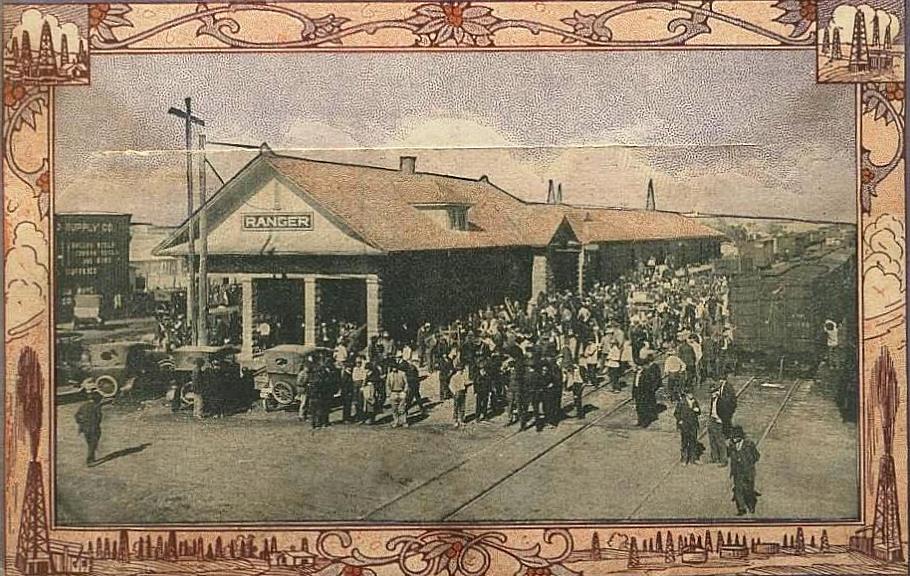

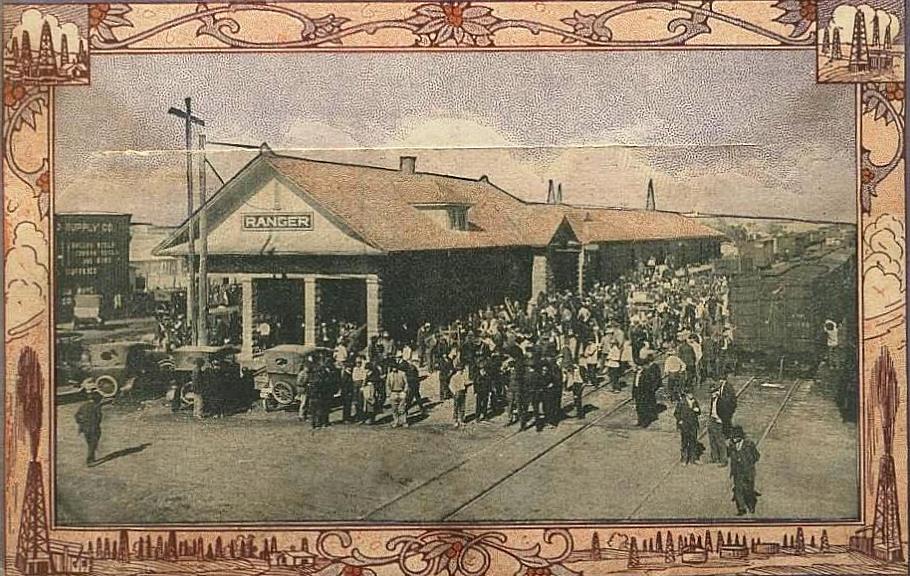

Following the October 1917 oilfield discovery, the Texas and Pacific Railroad transported people, equipment, and petroleum in and out of Ranger. A circa 1920 postcard shows the depot, future home of the Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum.

When completed, “Roaring Ranger” initially produced 1,600 barrels of high-gravity oil per day. Later oil gushers yielded up to 10,000 barrels of oil daily. Within 20 months, Texas and Pacific Coal Company stock jumped from $30 a share to $1,250 a share.

The suddenly wealthy petroleum exploration company added “oil” to its name, reorganizing as the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

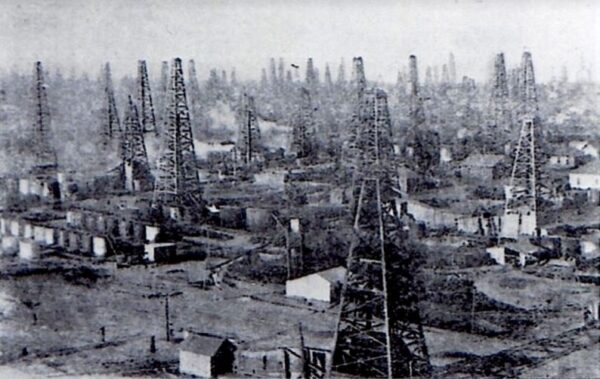

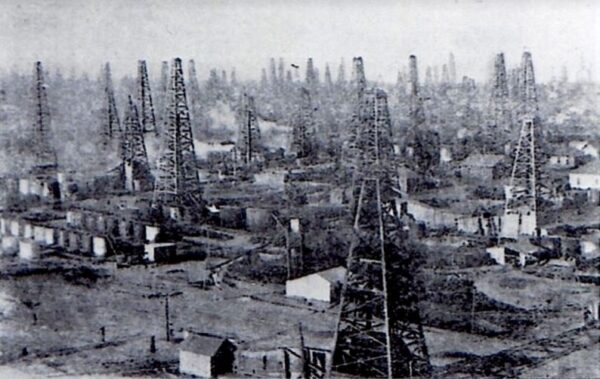

“Almost overnight, you couldn’t even see the homes for the derricks,” said Ranger historian Jeane B. Pruett. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Eastland County oil discoveries brought economic booms to Ranger, Cisco, and Desdemona — today a ghost town. As leasing intensified in and around Desdemona by 1918, convincing the congregation of a Baptist Church to allow drilling proved to be a challenge (see Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church).

Among the veterans visiting booming Eastland County after the war was a young Conrad Hilton, who visited Cisco intending to buy a bank. When he witnessed the long line of roughnecks waiting for a room at the Mobley Hotel, he decided to buy the hotel (see Oil Boom Brings First Hilton Hotel).

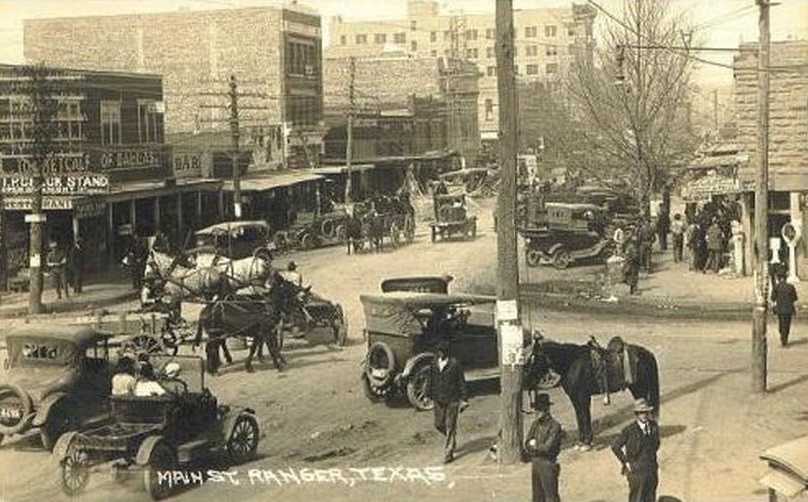

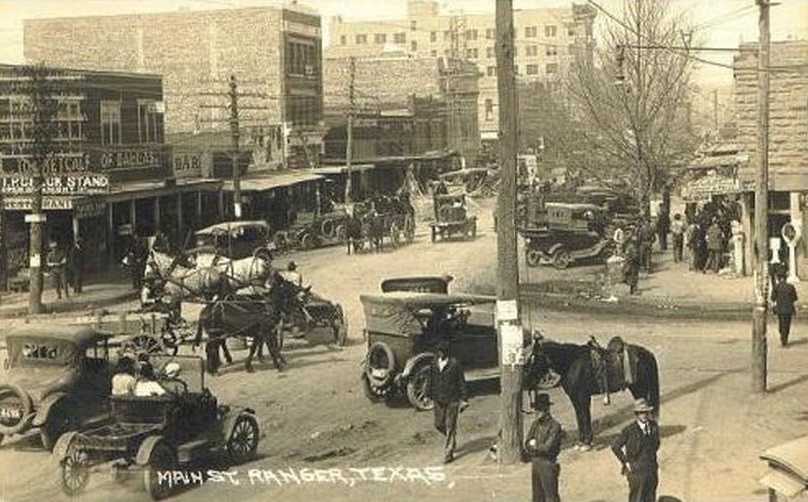

The Abilene Reporter-News reported Ranger’s population swelled from less than 1,000 to more than 30,000 — mostly men. Opportunities for illicit financial gain also attracted notorious oilfield hucksters like J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth (see Exploiting North Texas Oil Fever).

The 2016 Roaring Ranger Day Parade took place on the 99th birthday of the town’s famous oil gusher. Photo courtesy Ranger Historical Preservation Society.

Eastland County’s drilling and production boom grew rapidly as petroleum companies rushed to Ranger to develop the giant oilfield, according to historian Damon Sasser.

By 1919, the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company had 22 oil wells — and eight refineries open or under construction. More freight was unloaded in Ranger by the railroad than at any other place upon its line, including stations in Fort Worth, Dallas and New Orleans.

The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 discovery well of October 1917 created a mammoth oil boom at Ranger and across Eastland County, Texas. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

The flood of people also brought Texas Rangers to the boom town, which had begun as a Ranger camp in the 1870s. When Ranger jails overflowed, the lawmen handcuffed prisoners to telephone poles.

Meanwhile, independent and major exploration companies discovered nearby oilfields, including the Parsons, Sinclair-Earnest, and Lake Sand fields.

Photos courtesy Sarah Reveley and Barclay Gibson, who have photographed Texas Historical Commission markers and helped locate hundreds of historic sites from Louisiana to New Mexico.

Production from the Breckenridge oilfield in neighboring Stephens County was 10 million barrels of oil by 1919. It peaked at more than 31 million barrels of oil in 1921.

“Wave of Oil” wins WW I

“Roaring Ranger” and the region’s production had proved essential to the Allied victory in World War I. When the armistice was signed in 1918, a member of the British War Cabinet declared, “The Allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil.”

Ranger’s boom ended in the early 1920s when excess oil production caused wells to fail, but the discoveries confirmed the existence of a large petroleum-producing region, the Mid-Continent, with hundreds of oilfields stretching from Texas into Oklahoma and Kansas.

Eastland County oil discoveries, which began with the “Roaring Ranger” well of 1917, brought economic booms to Ranger, Cisco, and Desdemona. Photo courtesy Jeane B. Pruett and the family of W.K. Gordon Jr.

Established by the Ranger chamber of commerce in 1982, the Roaring Ranger Oil Boom Museum — inside the original Texas and Pacific Railway’s depot — exhibits drilling equipment, historic photos and a vintage cable-tool rig.

Ranger residents annually celebrate their 1917 oilfield discovery with a festival and parade down Main Street. When the parade crosses the historic train depot’s tracks, participants pass a small, gray granite marker dedicated to the “First Oil Well Drilled in Eastland County.”

The 1936 Texas Centennial marker remains “a highly cherished monument that Ranger should be very proud of,” according to Eastland County resident Sarah Reveley, who documented many Texas Historical Commission sites.

Other dedicated advocates for preserving local petroleum history included Jeane B. Pruett (1935-2022), a longtime friend of the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Ranger, Images of America (2010); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

(2010); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Roaring Ranger wins WWI.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/roaring-ranger-wins-wwi. Last Updated: October 10, 2025. Original Published Date: July 1, 2004.

by Bruce Wells | Aug 1, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

At the start of the 20th century, a growing number of Mid-Continent oilfields began their long history of oil discoveries. With them came the drilling boom and bust cycles of the U.S. petroleum industry. Major oilfield discoveries in North Texas during and after World War I, launched new, inexperienced ventures, including Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company

Although oil wealth would helped build Wichita Falls schools, infrastructure, hotels, banks, churches, and civic pride, competition increasingly made drilling prospects hard to come by. Oilfield equipment costs rose as excessive production lowered oil prices.

New oil exploration and production companies often arrived too late and went bankrupt without drilling single well. This did not discourage the rush for new investors (see Exploiting North Texas Fever).

A 1918 oil discovery near Wichita Falls joined earlier discoveries at Electra (1911) and Ranger (1917) to make Texas a worldwide leader in petroleum production.

The Texas Panhandle oil drilling boom began when the giant Ranger oilfield was discovered in October 1917 near Electra — where a 1911 shallow oilfield discovery already had attracted drillers. The “Roaring Ranger” well alone reached a daily production of 1,700 barrels of oil. The giant oilfield helped fuel the Allies’ victory in World War I.

Meanwhile, Conrad Hilton, who visited the Ranger area intending to buy a bank, saw the crowds of oilfield roughnecks and bought his first motel in nearby Cisco instead — learn more in Oil Boom Brings First Hilton Hotel.

Boom Town Burkburnett

Just outside Wichita Falls, at Burkburnett on July 29, 1918, a wildcat well erupted on S.L. Fowler’s farm just north of Wichita Falls near the Red River border with Oklahoma.

The new drilling boom made Burkburnett yet another famous American boom town. Two decades later it inspired the popular 1940 motion picture, “Boom Town,” which won an Academy Award. The oilfield drama featured Clark Gable (himself a former Oklahoma roughneck), Spencer Tracy, Claudette Colbert and Hedy Lamarr.

Even prior to the Burkburnett discovery, North Texas oilfields were producing half of all the state’s oil. Wichita Falls prospered and the town’s railroad line expanded. Refineries began to appear in 1915. That year Wichita County reported 1,025 producing wells.

In 1920 there were 47 factories within Wichita Falls. One year later the Wichita Falls and Southern Railroad Company added an extension for trains between Wichita Falls, Ranger and Fort Worth.

Sunshine State Oil & Refining

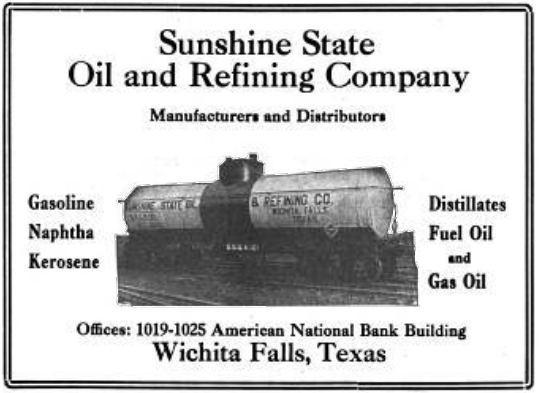

Among those rushing to the region’s boom towns was Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company, which incorporated in New Mexico on April 21, 1917. The new company set up its main operations in Wichita Falls capitalized at only $300,000.

Although Wichita Falls already hosted no less than nine competing independent refineries, the company built its own 3.5 miles north of town with an initial capacity of 1,250 barrels of oil a day that grew to 2,500 barrels of oil a day.

By 1920, Sunshine State Oil & Refining had increased capitalization to $650,000 and secured ownership of a 45-mile pipeline to connect with oil producers in the Burkburnett and Kemp-Munger-Allen fields.

Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company had offices in the American National Bank Building in Wichita Falls, Texas.

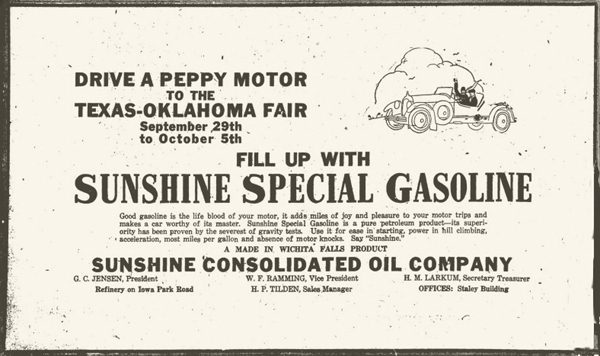

By July 1922 the company marketed its brand of gasoline and kerosene in Wichita Falls, Burkburnett, Electra, and Gainsville. It also explored opportunities in Eddy and Chavez counties in New Mexico to secure further oil supplies.

The company sold its finished products, principally gasoline and kerosene, in railroad tank cars and managed a fleet that grew from 50 cars to 150 cars. “Manufacturers and Distributors – Gasolene, Naptha, Kerosene Distillates, Fuel Oil and Gas Oils,” proclaimed advertisements with the registered trade name of “Sunshine Special” for products.

Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company was reported to pay 100 percent dividends – but those dividends were paid in shares of company stock. To raise money, the company increased capitalization again and issued more stock.

However, a refining company’s margin for success was inevitably linked to the cost of crude oil and the price of refined petroleum products.

Sunshine State Oil & Refining sold its finished products in railroad tank cars and managed a fleet that grew from 50 cars to 150 cars.

Small independents faced additional challenges, as Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company President George C. Jensen would later note:

“The larger companies will pay posted price and the only way that the independent refineries are able to buy crude oil is to offer a large bonus, in some cases as much as 40 cents per barrel premium over prices paid by Standard Oil,” Jensen complained to Petroleum Magazine’s “Open Forum” readers. “They consequently cannot make a fair profit on refined products.”

Under these and other market pressures, Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company’s refinery began to operate well below capacity.

Sunshine sets in North Texas

As the drilling industry and the refineries competed, Wichita Falls prospered, thanks to “Black Gold.” The city added a municipal auditorium in 1927 and an airline passenger service in 1928 – the same year the city’s first commercial broadcasting station, KGKO, was established.

However, as early as July 1924 Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company was struggling with debt. The company issued more stock to raise capitalization to $1.5 million and in an agreement with shareholders changed its name to Sunshine Consolidated Oil Company.

Shareholders had to exchange their old stock certificates for the new Sunshine Consolidated Oil shares. The old Sunshine certificates were canceled. Efforts to sell new shares on the New York “curb market” did not fare well.

“Say Sunshine” advises this card for newly renamed but still financially troubled Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company and its “made in Wichita Falls product.”

As fundraising efforts failed, creditors forced the renamed company into receivership, which was contested but ultimately adjudicated by the 89th District Court in Texas. Assets were sold off to pay creditors. By November 5, 1925, the Corsicana Daily Sun reported:

A sale involving a cash consideration of $159,000 was consummated in the Wichita Falls oil district Wednesday when Bridwell & Heydrick closed a deal with receiver of the Sunshine Consolidated Oil Company whereby a number of leases in the Sunshine State and Freeman Hampton pools of Archer county changed hands.

After an intense and competitive seven years in business, Sunshine/Consolidated Oil Company failed, joining other oilfield ventures in the high-risk business of petroleum exploration, production and refining. The industry’s boom and bust cycles continue to this day.

North Texas petroleum prosperity began on April 1, 1911, when geyser of oil erupted at the Clayco No. 1 well at Electra,which would later be awarded the title of “ Pump Jack Capital of Texas.”

More stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/sunshine-state-oil-refining-company. Last Updated: August 2, 2022. Original Published Date: July 22, 2018.

(2010); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.