by Bruce Wells | Apr 9, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

John Wilkes Booth and his actor friends drilled for Pennsylvania oil in 1864 — and found it.

After forming an oil company and drilling for “black gold” in booming northwestern Pennsylvania, the actor’s dreams of a petroleum fortune collapsed in June 1864. He then sought fame as a martyr to the Confederacy. A failed oilman turned assassin.

As the Civil War approached its bloody conclusion, John Wilkes Booth in January 1864 made the first of several trips to Franklin, Pennsylvania, where he purchased an oil lease on the Fuller farm. Maps reveal the three-acre strip of land on the farm, about one mile south of Franklin and on the east side of the Allegheny River. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Apr 1, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

The brief oilfield journey of a “staveless” wooden barrel maker.

The U.S. petroleum industry was barely a decade old and as oil discoveries spread from northwestern Pennsylvania’s first commercial well, efficiently transporting the resource became critical. In Brooklyn, New York, the Staveless Barrel and Tank Company organized. The company hoped to exploit a new patent for making barrels.

Capitalized in 1867 at $500,000 with 5,000 shares at $100 each, Staveless Barrel and Tank’s barrel-making process included, “application of scale-boards or veneers in layers, the direction of whose grain is crossed or diversified, and which are connected together, forming a material for the construction, lining, or covering of land and marine structures.” (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Mar 25, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Finding oil near natural seeps in Indian Territory.

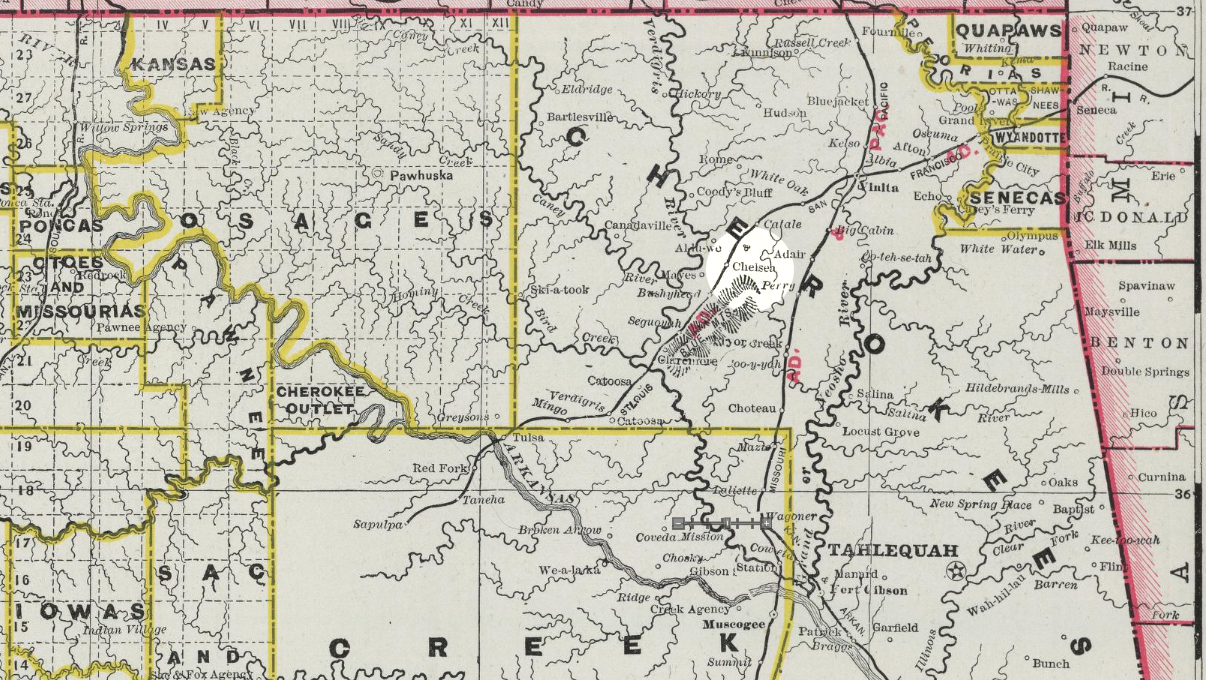

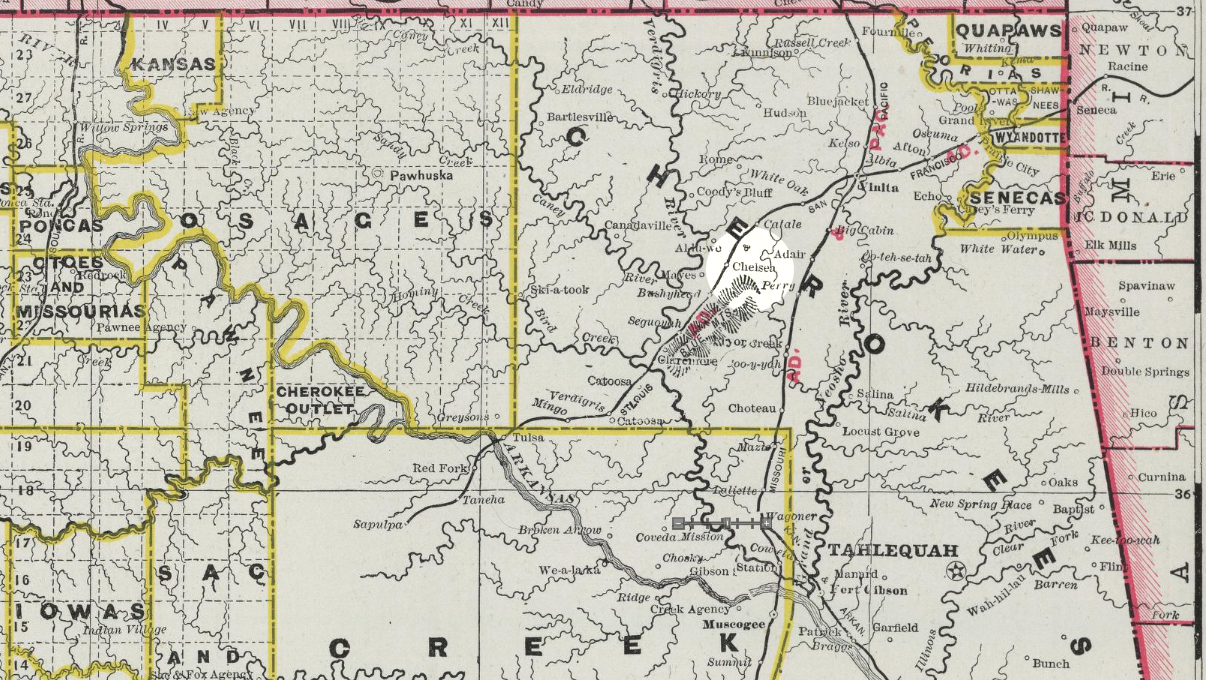

Drilled near petroleum seeps in 1889 and completed one year later southwest of Chelsea in Indian Territory, the story of Edward Byrd’s oil well in the Cherokee Nation is not as well known as the “Bartlesville gusher” of 1897, the official first Oklahoma oil well.

What would become known as the Indian Territory began when President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The legislation established a process where the president could forcibly relocate native American tribes westward.

Chelsea began in 1881 as a railroad stop in the Cherokee Nation. Its oil well was drilled in 1889 and completed a year later, producing half a barrel of oil per day from 36 feet deep.

Land “remote from white settlements” west of Arkansas was deemed the best place to settle the tribes, according to The Five Civilized Tribes: Indian Territory, a 1900 article in the annual Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York (vol. XXXII).

Title and deed gave ownership of the land to the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek, and Cherokee where they could establish tribal governments under the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“It was intended to settle them there for all time, whereby they could live to themselves, according to their own pleasure, with self-government, under the protection of the general Government,” notes C.H. Fitch, author of the Journal article.

However, westward growth and legislation such as the Dawes Act (1887) and Curtis Act (1898) ultimately stripped the tribal governments of their authority. Their designated tribal lands were reduced from about 150 million acres to 78 million acres as America’s search for petroleum reached into Indian Territory.

Oil in Indian Territory

In 1882, Edward Byrd, a Cherokee by marriage, found oil seeps southwest of Chelsea in Indian Territory. Two years later, the Cherokee Nation passed a law authorizing the organization of a company “for the purpose of finding petroleum, or rock oil, and thus increasing the revenue of the Cherokee Nation.”

Seven years earlier than a headline-making 1897 gusher at Bartlesville in the Cherokee Nation, the United States Oil and Gas Company completed an oil well at Chelsea, about 35 miles southeast.

Leases were limited to Cherokee citizens, and in 1887 Byrd organized the United States Oil and Gas Company with his partner William B. Linn of Pennsylvania, home of the first U.S. oil well of 1859. The company had a contingent of four Kansas investors, William Woodman, Finley Ross, Oak Daeson and Martin Hellar.

Byrd’s petroleum exploration venture secured a 100,000-acre lease from the Cherokee Nation west of Chelsea, between the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway and the Verdigris River. The lease covered portions of present-day Rogers and Nowata counties in Oklahoma.

In 1890, United States Oil and Gas completed its first well on Spencer Creek, within yards of Byrd’s old oil seeps, using basic technologies for “making hole.” This Indian Territory well produced oil seven years before the Bartlesville well — but just half a barrel of oil a day from 36 feet deep.

Ten more marginal wells followed, and by the last quarter of 1891, the company reported a total of “twelve barrels of oil pumped” in what became the Chelsea-Alluwe field.

With little production and no large commercial market nearby, Byrd’s venture shut down. He then organized a group of Cherokee citizens into the Hugh B. Henry and Company and secured additional leases covering thousands of acres for United States Oil and Gas.

Cherokee Oil and Gas

John B. Phillips, an experienced independent oil producer from Butler, Pennsylvania, formed Cherokee Oil and Gas Company to take over United States Oil and Gas properties.

Under federal law, the leases had to be approved by the Department of the Interior, which reduced the size from more than 100,000 acres to 12,000 acres. Cherokee Oil and Gas also bought the 11 shallow, marginal wells of United States Oil and Gas wells for “twenty-five cents on the dollar.”

Cherokee Oil and Gas drilled deeper wells and found high-grade oil in two wells (1,450 feet deep and 1,320 feet deep) before a boiler explosion shut both wells down. Other small producing wells followed as the company continued drilling.

Meanwhile, another Indian Territory company explored near Bartlesville oil seeps, about 40 miles west. On April 15, 1897, the Cudahy Oil Company “shot” with nitroglycerin the company’s Nellie Johnstone No.1 well after finding signs of oil in March. This oilfield discovery well began producing up to 75 barrels of oil a day from 1,320 feet deep.

Despite the production, Cudahy Oil was confronted with a lack of infrastructure for moving oil to markets. With no storage tanks, pipelines or railroads available, the Nellie Johnstone No. 1 was capped for two years.

In 1898, Congress passed the Curtis Act, “for the Protection of the People of Indian Territory.” The new law, amending the Dawes Act of 1887, is described by the Oklahoma Historical Society as “the culmination of legislation designed to strip tribal governments of their authority and give it to Congress and/or the federal government.”

In Indian Territory oilfields, operations were brought to a standstill because of difficulties with titles, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. “The title of the oil and minerals remains in trust with the United States Government under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior, who must ratify every lease to make it valid.”

The legislation also stipulated, “The amount of 640 acres can only be acquired by a single individual or company.”

An 1890 marginal producing well at Chelsea could be considered Oklahoma’s first petroleum production.

However, both the Cherokee Oil and Gas Company and the Cudahy Oil Company had leased more than 300,000 acres from the Cherokee Nation before the Curtis Act. Congressional hearings and litigation followed.

In 1902, the Superior Court of the District of Columbia upheld “the power of the Secretary of the Interior to lease Cherokee oil lands,” in litigation over a lease of 12,000 acres held by the Cherokee Oil and Gas Company. Cudahy Oil’s prospects were profoundly affected as well.

In 1904, the Los Angeles Herald reported on the pending merger of Cherokee Oil and Gas Company with Cudahy Oil Company to form a new combined enterprise, the Cudahy Pipe Line and Refining Company.

The merger never took place, although the combined assets reportedly amounted to 137 producing wells on the Cherokee Oil and Gas property and 87 producing wells on Cudahy leases for a total production of 2,100 barrels of oil a day.

“The producers are rather chary about signing up with the Cudahy concern,” noted the Weekly Examiner of Bartlesville in 1905. “An effort is being made to sell stock to the producers, but it is said the latter are not falling over each other in an effort to get on the independent band wagon.”

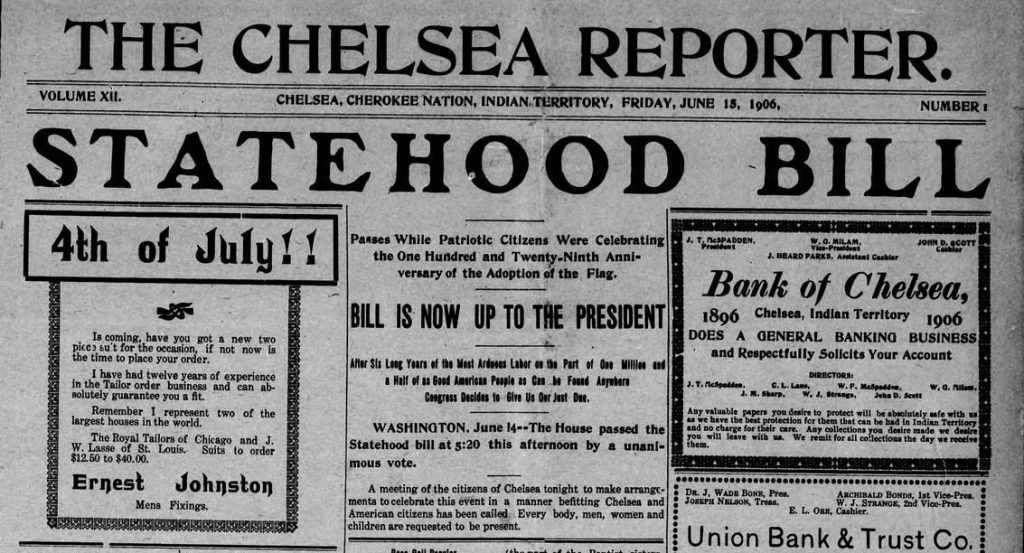

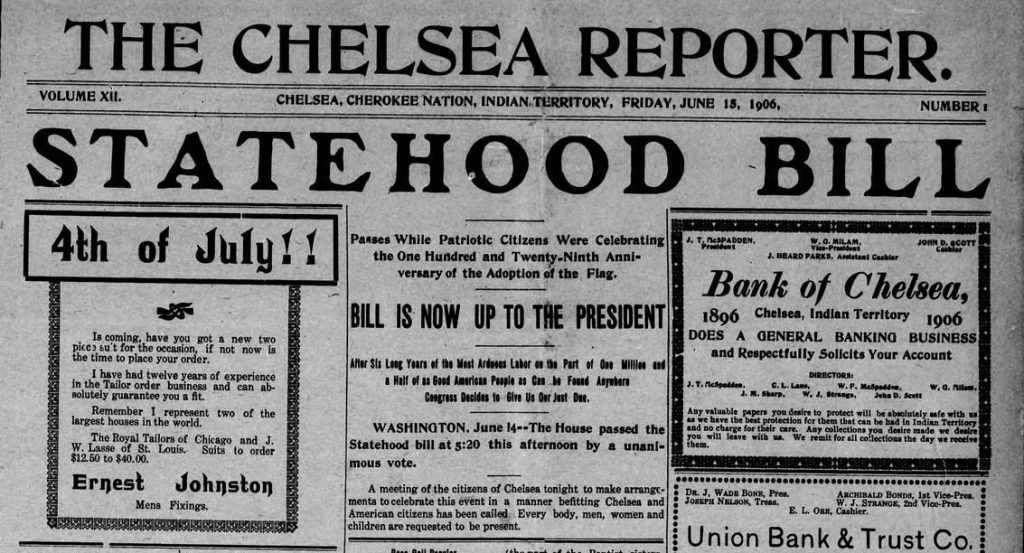

With the Curtis Act having cleared the last impediment to statehood, Oklahoma became the 46th state on November 16, 1907. Cherokee Oil and Gas Company continued to operate and by 1918, the company owned half-interest in 375 oil wells at Chelsea.

Old Faucett Well

Although the 1890 marginal oil producer at Chelsea could be called Oklahoma’s first, records show that in the Choctaw Nation, a well was completed by Dr. H.W. Faucett and Choctaw Oil and Refining Company.

The well drilled in the Choctaw Nation also has a claim to the “first Oklahoma oil well” title. The discovery on Choctaw land reached 1,400 feet deep, where it produced some oil — but not in commercial quantities. The “Old Faucett Well” of 1890 was abandoned after Dr. Fawcett fell ill and died later that year.

The Cherokee-Warren Oil and Gas Company (incorporated on March 31, 1919) took over the remaining assets of Faucett’s Choctaw Oil and Refining Company, the venture that had drilled another of Oklahoma’s first oil wells.

However, the 1897 gusher at Bartlesville officially remains the Sooner State’s first oil well. A replica cable-tool derrick of the Nellie Johnstone No. 1 can be found at Discovery 1 Park in Bartlesville. The wooden, 84-foot derrick produces a popular water-gushing demonstration among other petroleum exhibits, including an oilfield firefighting cannon.

__________________________

Recommended Reading: Oil in Oklahoma (1976); Oil And Gas In Oklahoma: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma

(1976); Oil And Gas In Oklahoma: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma (2013); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry

(2013); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry (1980); Conoco: 125 Years of Energy

(1980); Conoco: 125 Years of Energy (2000); Phillips, The First 66 Years

(2000); Phillips, The First 66 Years (1983). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1983). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

__________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. Contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Another First Oklahoma Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K. L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/another-first-oklahoma-oil-well. Last Updated: March 31, 2025. Original Published Date: March 9, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 3, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Louisiana oil boom brings pipelines, refineries and competition.

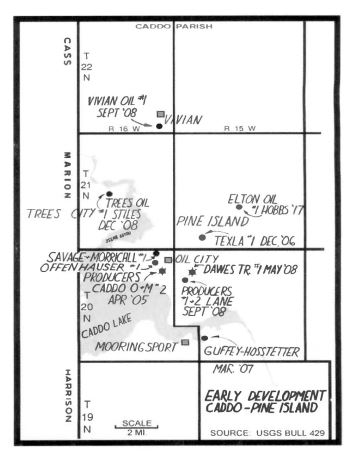

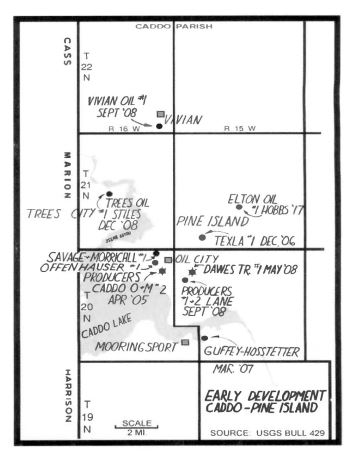

Claiborne Parish made headlines on January 12, 1919, when Consolidated Progressive Oil Company completed the discovery well for northern Louisiana’s prolific Homer oilfield. About 50 miles to the west, a 1905 oil discovery at Caddo-Pines near Shreveport had brought a rush of oil exploration to northern Louisiana.

Caddo Lake drilling platforms – completed over water without a pier to shore – have been called America’s first true offshore oil wells. Exhibits at the state’s Oil City museum tell that story. Like Caddo-Pines, the Homer field was crowded with new companies within months after the discovery.

Petroleum production from the new field soon reached an aggregate of about 10,000 barrels of oil per day. Reporting from the Pennsylvania oil regions, Pittsburgh Press on September 21, 1919, proclaimed the “Homer Field is Sensation of Oil Industry.”

Detail from a panoramic “bird’s eye view” of the Homer oilfield circa 1920s. Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Superior Oil Works

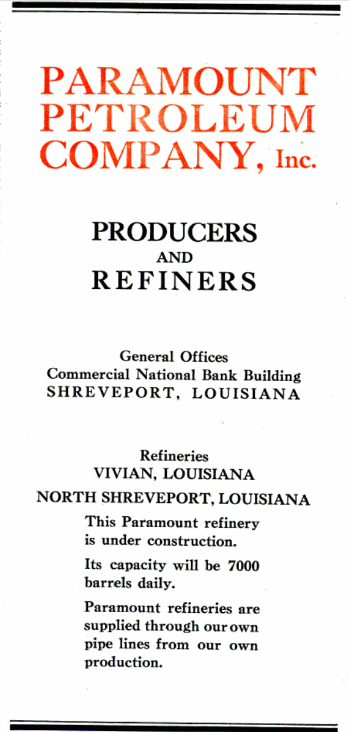

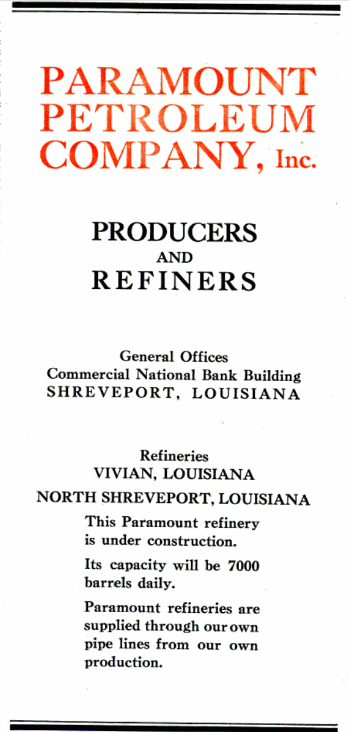

Paramount Petroleum Company began when the leadership of another company operating in the Homer oilfield decided to expand operations. Superior Oil Works officers, including President George A. Todd of Oklahoma City; Secretary and Purchasing Agent H.H. Todd of Vivian, Louisiana; and Treasurer D.C. Richardson of Shreveport organized the Paramount Petroleum Company.

Superior Oil Works had been formed to build and operate a refinery close to the Homer field. Capitalized at $300,000 with common stock issued, the company began construction in Superior, Louisiana, but its officers were by then contemplating the much-expanded venture — the formation of Paramount Petroleum to integrate exploration, production, transportation and refining under one organization.

Once established, the new company absorbed Superior Oil Works and looked for potential leases near the Consolidated Progressive Oil Company’s discovery well. As construction of the Superior refinery progressed, purchasing agent H.H. Todd advertised that Paramount Petroleum was “in the market for oil refinery equipment, boilers, stills, pumps, and plant machinery, etc.”

Paramount Petroleum made a deal with Consolidated Progressive Oil in May 1919, securing one-half interest in more than 11,000 acres of both proven and unexplored territory in Claiborne Parish. The acreage was already producing about 40,000 barrels of oil, ensuring the refinery would be supplied.

“A giant refining company has been organized recently in Shreveport to be known as the Paramount Petroleum Company,” noted the Oil Distribution News. The venture was capitalized at $10 million with half of its stock subscribed.

“Stock in this company has been consumed by the largest business and banking men of Shreveport,” added the Oil and Gas News. But the best news for investors was the headline: “Paramount Petroleum Gets 10,000 Barrel Well And Will Build Big Refinery.”

In March 1920, the Petroleum Age reported Paramount Petroleum “recently took over the under-construction Superior Oil Works refinery at Vivian [Superior], Louisiana, 23 miles north of Shreveport, to service Pine Island production.”

The publication added that another refinery was to be completed in north Shreveport in November 1920 “with a four-inch pipeline from the Homer field where Paramount Petroleum holds 4,700 acres.”

Paramount Petroleum Company’s newest refinery would be struggling by May 1921.

Within a month Paramount Petroleum was drilling in Claiborne Parish and shipping 400,600 barrels of oil a day. The company secured a $1 million mortgage from the Commercial National Bank of Shreveport and advertised, “Paramount refineries are supplied through our own pipelines from our own production.”

Paramount Petroleum in July 1920 completed the No. 5 Shaw well, which produced 500 barrels of oil a day from 2,090 feet deep in the Homer field. In August, the company’s No. 9 Shaw well become another 500-barrels-of-oil-a-day producer from a depth of 2,100 feet.

Anticipating more growth in oil production, Paramount Petroleum committed to an agreement for 300 tank cars from Standard Tank Car Company of St. Louis, Missouri.

“Not too bright”

“Paramount has just closed a deal for one half interest in 24 producing wells in the old Caddo field with 1,200 acres of proven territory on which many wells can yet be drilled,” reported the Petroleum Age in October 1920. “The production department of Paramount Petroleum is making splendid headway and with its large acreage, will no doubt greatly add to the earnings of the company.”

But the Petroleum Age reporter had got it wrong. By February 1921, Paramount Petroleum’s refinery at Superior was running at only about 50 percent capacity. Another trade publication reported the company’s prospects as “not too bright.”

Shipments from Paramount Petroleum’s Homer oilfield holdings dropped to just 168 barrels of oil a day. In May 1921 the struggling company leased its underused refinery and fleet of 390 tank cars to Lucky Six Oil Company for six months.

The Homer field attracted drillers from earlier discoveries at the nearby Caddo-Pines oilfields. Photo courtesy the Petroleum History Institute.

To the south, the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 oil gusher on January 10, 1921, had opened Arkansas’ El Dorado field and Lucky Six Oil Company had entered the scramble to exploit the new field’s huge production (578,000 barrels of oil in the month of May alone).

The oilfield discovery 15 miles north of the Louisiana border was the first Arkansas oil well. It attracted even more exploration and production companies to the region.

As competition intensified, Paramount Petroleum struggled to pay debts. It was unable to make a required $200,000 mortgage payment to Commercial National Bank of Shreveport in July 1921. The deal Paramount had struck with Consolidated Progressive Oil back in 1919 had become toxic.

The National Petroleum News reported on September 7, 1921, that Consolidated Progressive Oil was seeking a court-ordered receiver to take over Paramount Petroleum. The action was based on claims totaling $849,547 — and “averred acts jeopardizing the interests of creditors.” Among the allegations was “the effect that officials of the defendant concern have admitted in writing the company’s inability to meet present and maturing obligations.”

Paramount Petroleum’s epitaph was brief. “It is officially stated that this company is out of business,” reported Poor’s Cumulative Service in December 1921. “Its properties are to be sold by the sheriff December 24 and proceeds applied on the first Mortgage notes.”

The first Louisiana oil well had been drilled 17 years before the end of Paramount Petroleum. More stories about petroleum exploration and production companies trying to join drilling booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

______________________

Recommended Reading: Louisiana’s Oil Heritage, Images of America (2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright AOGHS © 2025

Citation Information – Article Title: “Paramount Petroleum Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:httpshttps://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/paramount-petroleum-company. Last Updated: March 9, 2025. Original Published Date: August 15, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 17, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Oklahoma showman Maj. Gordon W. “Pawnee Bill” Lillie caught oil fever in 1918.

With America joining “the war to end all wars” in Europe and oil demand rising, a popular Oklahoma showman launched his own petroleum exploration and refining company.

Although not as well known as his friend Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody of Wyoming, Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie was “a showman, a teacher, and friend of the Indian,” according to his biographer.

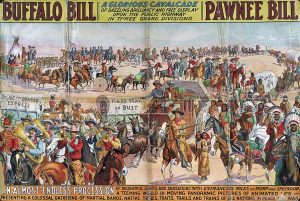

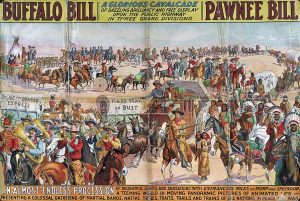

Pawnee Bill and Buffalo Bill combined their shows from 1908 to 1913 as “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East.”

Maj. Lillie was admired for being a “colonizer in Oklahoma and builder of his state,” noted Stillwater journalist Glenn Shirley in his 1958 book Pawnee Bill: A Biography of Major Gordon W. Lillie.

The two entertainers joined their shows in 1908 to form “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East,” promoted as “a glorious cavalcade of dazzling brilliancy,” noted Shirley, adding that the combined shows offered, “an almost endless procession of delightful sight and sensations.”

But times were changing as public taste turned to a new form of entertainment, motion picture shows. By 1913, the two showmen’s partnership was over and their western cavalcade foreclosed. Lillie turned to other ventures — real estate, banking, ranching, and like his former partner Cody, the petroleum industry.

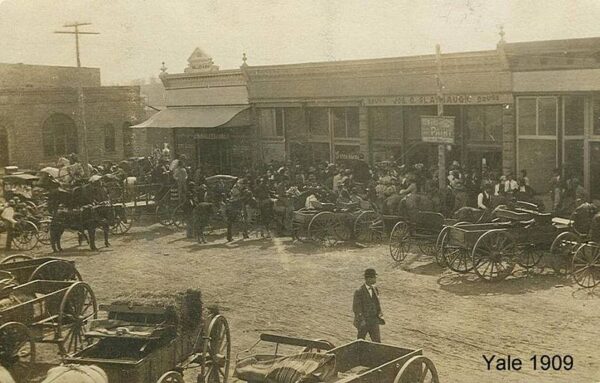

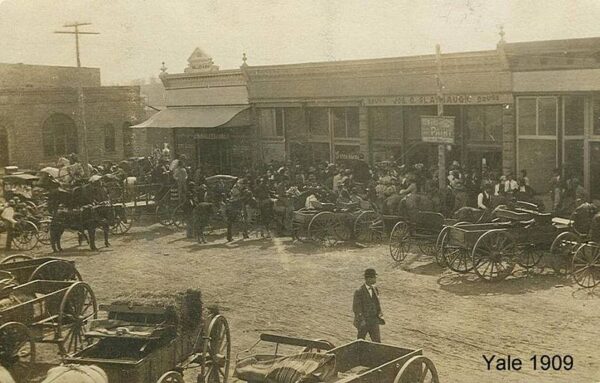

Oklahoma oilfield discoveries near Yale (population of only 685 in 1913) had created a drilling boom that made it home to 20 oil companies and 14 refineries. In 1916, Petrol Refining Company added a 1,000-barrel-a-day-capacity plant in Yale, about 25 miles south of Lillie’s ranch.

The trade magazine Petroleum Age, which had covered the 1917 “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery in Texas, reported that for Pawnee Bill, “the lure of the oil game was too strong to overcome.”

Obsolete financial stock certificates with interesting histories like Pawnee Bill Oil Company are valued by collectors.

The Oklahoma showman founded the Pawnee Bill Oil Company on February 25, 1918, and bought Petrol Refining’s new “skimming” refinery in March.

An early type of refining, skimming (or topping) removed light oils, gasoline and kerosene and left a residual oil that could also be sold as a basic fuel. To meet the growing demand for kerosene lamp fuel, early refineries built west of the Mississippi River often used the inefficient but simple process.

Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie (1860-1942).

Lillie’s company became known as Pawnee Bill Oil & Refining and contracted with the Twin State Oil Company for oil from nearby leases in Payne County.

Under headlines like “Pawnee Bill In Oil” and “Hero of Frontier Days Tries the Biggest Game in All the World,” the Petroleum Age proclaimed:

“Pawnee Bill, sole survivor of that heroic band of men who spread the romance of the frontier days over the world…who used to scout on the ragged edge of semi-savage civilization, is doing his bit to supply Uncle Sam and his allies with the stuff that enables armies to save civilization.”

Post WWI Bust

By July 30, 1919, Pawnee Bill Oil (and Refining) Company had leased 25 railroad tank cars, each with a capacity of about 8,300 gallons. But the end of “the war to end all wars” drastically reduced demand for oil and refined petroleum products. Just two years later, Oklahoma refineries were operating at about 50 percent capacity, with 39 plants shut down.

Although Lillie’s refinery was among those closed, he did not give up. In February 1921, he incorporated the Buffalo Refining Company and took over the Yale refinery’s operations. He was president and treasurer of the new company. But by June 1922, the Yale refinery was making daily runs of 700 barrels of oil, about half its skimming capacity.

The Pawnee Bill Oil Company held its annual stockholders meetings in Yale, Oklahoma, an oil boom town about 20 miles from Pawnee Bill’s ranch.

“At the annual stockholders’ meeting held at the offices of the Pawnee Bill Oil Company in Yale, Oklahoma, in April, it was voted to declare an eight percent dividend,” reported the Wichita Daily Eagle. “The officers and directors have been highly complimented for their judicious and able handling, of the affairs of the company through the strenuous times the oil industry has passed through since the Armistice was signed.”

The Kansas newspaper added that although many Independent refineries had been sold at receivers’ sale, “the financial condition of the Pawnee Bill company is in fine shape,”

Buffalo Bill’s Shoshone Oil

What happened next has been hard to determine since financial records of the Pawnee Bill Oil Company are rare. A 1918 stock certificate signed by Lillie, valued by collectors one hundred years later, could be found selling online for about $2,500.

Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie’s friend and partner Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody also caught oil fever, forming several Wyoming oil exploration ventures, including the Shoshone Oil Company.

In 1920, yet another legend of the Old West — lawman and gambler Wyatt Earp — began his a search for oil riches on a piece of California scrubland. One century later, his Kern County lease still paid royalties; learn more in Wyatt Earp’s California Oil Wells.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Pawnee Bill: A Biography of Major Gordon W. Lillie (1958). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1958). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Pawnee Bill Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/pawnee-bill-oil-company. Last Updated: February 19, 2025. Original Published Date: February 24, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 4, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

A 1954 well drilled by the Ohio Oil Company reached more than four miles deep.

Founded in 1887 by Henry M. Ernst, the Ohio Oil Company got its exploration and production start in northwestern Ohio, at the time a leading oil-producing region. Two years later, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust purchased the growing company — known as “The Ohio” — and in 1905 moved headquarters from Lima to Findlay.

Soon establishing itself as a major pipeline company, by 1908 the Ohio controlled half of the oil production in three states. The company resumed independent operation in 1911 following the dissolution of the Standard Oil monopoly. The new Ohio Oil’s exploration operations expanded into Wyoming and further westward.

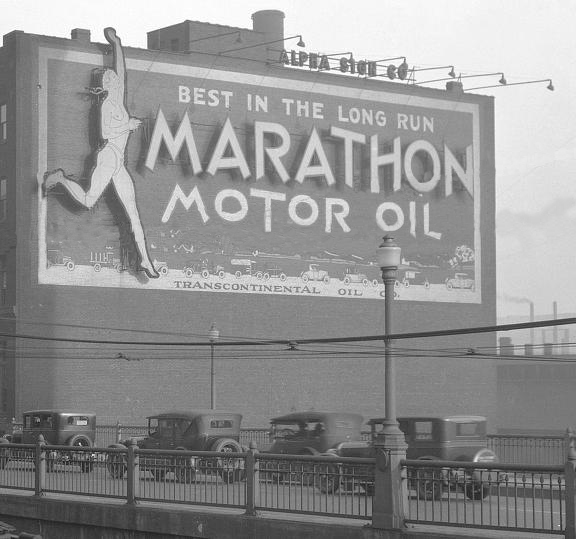

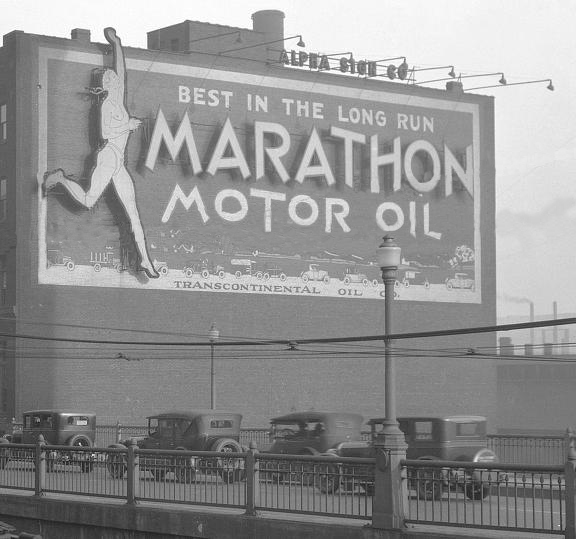

The Ohio Oil Company in 1930 purchased Transcontinental Oil, a refiner that had marketed gasoline under the trademark “Marathon” since 1920. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

By 1915, the company’s infrastructure had added 1,800 miles of pipeline as well as gathering and storage facilities from its newly acquired Illinois Pipe Line Company. The Ohio then purchased the Lincoln Oil Refining Company to better integrate and develop more crude oil outlets.

“Ohio Oil saw the increasing need for marketing their own products with the ever-increasing supply of automobiles appearing on the primitive roads,” explained Gary Drye in a 2006 forum at Oldgas.com.

The company ventured into marketing in June 1924 by purchasing Lincoln Oil Refining Company of Robinson, Illinois. With an assured supply of petroleum, the Ohio Oil’s “Linco” brand quickly expanded.

The Ohio Oil Company marketed its oil products as “Linco” after purchasing the Lincoln Oil Refinery in 1920. Undated photo of a station in Fremont, Ohio.

Meanwhile, a subsidiary in 1926 co-discovered the giant Yates oilfield in the Permian Basin of New Mexico and West Texas. “With huge successes in oil exploration and production ventures, Ohio Oil realized they needed even more retail outlets for their products,” Drye reported. By 1930, the company distributed Linco products throughout Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Kentucky.

Marathon of Ohio Oil

In 1930 Ohio Oil purchased Transcontinental Oil, a refiner that had marketed gasoline under the trademark “Marathon” across the Midwest and South since 1920. Acquiring the Marathon product name included the Pheidippides Greek runner trademark and the “Best in the long run” slogan.

Adopted in 2011, the third logo for corporate branding in Marathon Oil’s 124-year history.

According to Drye, Transcontinental “can best be remembered for a significant ‘first’ when in 1929 they opened several Marathon stations in Dallas, Texas in conjunction with Southland Ice Company’s ‘Tote’m’ stores (later 7-Eleven) creating the first gasoline/convenience store tie-in.”

The Marathon brand proved so popular that by World War II the name had replaced Linco at stations in the original five-state territory. After the war, Ohio Oil continued to purchase other companies and expand throughout the 1950s.

Ohio Oil’s California Record

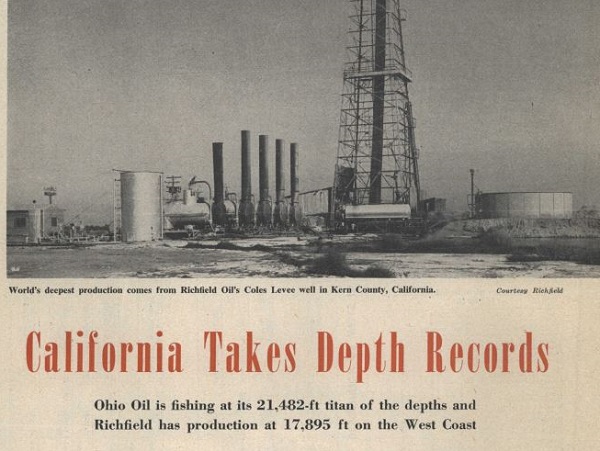

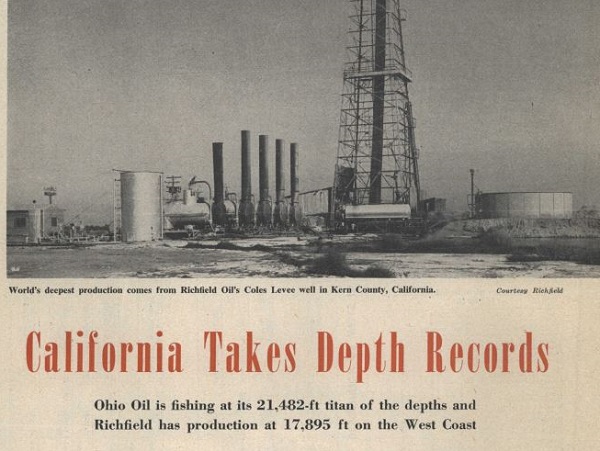

As deep drilling technologies continued to advance in the 1950s, a record depth of 21,482 feet was reached by the Ohio Oil Company in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

Petroleum Engineer magazine in 1954 noted the well set a record despite being “halted by a fishing job.”

The deep oil well drilling attempt about 17 miles southwest of Bakersfield in prolific Kern County, experienced many challenges. A final problem led to it being plugged with cement on December 31, 1954. At more than four miles deep, down-hole drilling technology of the time was not up to the task when the drill bit became stuck.

The challenge of retrieving obstructions from deep in a well’s borehole – “fishing” – has challenged the petroleum industry since the first tool stuck at 134 feet and ruined a well spudded just four days after the famous 1859 discovery by Edwin Drake in Pennsylvania (see The First Dry Hole).

In a 1954 article about deep drilling technology, The Petroleum Engineer noted the Kern County well of Ohio Oil — which would become Marathon Oil — set a record despite being “halted by a fishing job.” The well was a financial loss.

A 1953 Kern County well drilled by Richfield Oil Corporation produced oil from a depth of 17,895 feet, according to the magazine. At the time, the average U.S. cost for the nearly 100 wells drilled below 15,000 feet was about $550,000 per well. Learn more California petroleum exploration history by visiting the West Kern Oil Museum.

More than 630 exploratory wells with a total footage of almost three million feet were drilled in California during 1954, according to the American Association of Petroleum Geologists — the AAPG, established in 1917.

In 1962, celebrating its 75th anniversary, The Ohio changed its name to Marathon Oil Company and launched its new “M” in a hexagon shield logo design. Other milestones include:

1981 – U.S. Steel (USX) purchased the company.

1985 – Yates field produced its billionth barrel of oil.

1990 – Marathon opened headquarters in Houston.

2005 – Marathon became 100 percent owner of Marathon Ashland Petroleum LLC, which later became Marathon Petroleum Corp.

2011 – Completed a $3.5 billion investment in the Eagle Ford Shale play in Texas.

On June 30, 2011, Marathon Oil became an independent upstream company and unveiled an “energy wave” logo as it prepared to separate from Marathon Petroleum, based in Findlay. Read a more detailed history in Ohio Oil Company and visit the Hancock Historical Museum in Findlay.

On May 29, 2024, Marathon Oil announced it was being acquired by ConocoPhillips in an all-stock transaction valued at $22.5 billion.

______________________________

Recommended Reading: Portrait in Oil: How Ohio Oil Company Grew to Become Marathon (1962). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1962). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

______________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Marathon of Ohio Oil.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/marathon-ohio-oil. Last Updated: February 3, 2025. Original Published Date: December 28, 2014.