by Bruce Wells | Jan 22, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Rise and fall of a California oil exploration company.

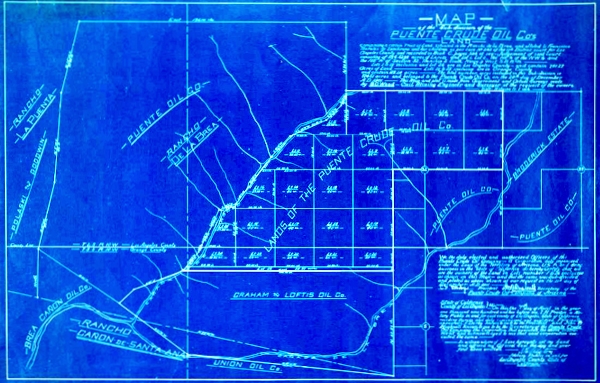

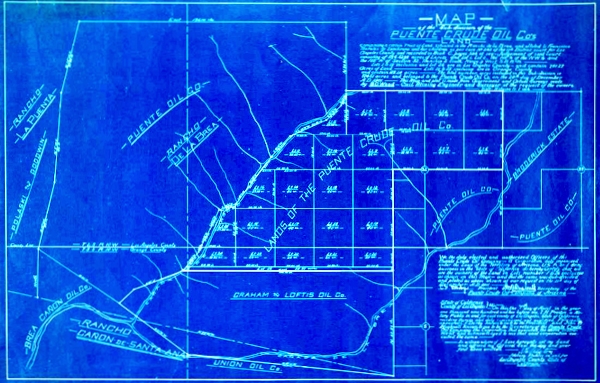

A new “black gold” rush in California took off in 1886 after William Rowland and partner William Lacy completed several producing oil wells at Rancho La Puente. Their company, Rowland & Lacy (later called the Puente Crude Oil Company), helped reveal the Puente oilfield.

The exploration venture — and a more successful one with a similar name, the Puente Oil Company — were among those seeking oil in southern California at the turn of the century. By 1912, many inexperienced companies had drilled more than 100 wells in the Fullerton area southeast of the Los Angeles field. Two expensive “dry holes” were completed by the Puente Crude Oil Company.

Puente Crude Oil Company was one of many small early 20th-century ventures hoping to find oil in southern California’s prolific oilfields at Brea Canyon and Fullerton.

Initially capitalized with $500,000, Puente Crude Oil offered stock to the public at 10 cents a share in 1900, but its two unsuccessful wells in the Puente field’s eastern extension brought the company to a quick financial crisis.

One well was lost to a “crooked hole” and the other found only traces of oil and natural gas as enthusiastic advertisements continued to solicit investment. Some ads referred to the widely known Sunset oilfield, discovered in 1892 in Kern County to the north.

By May 1901 company stock was offered at two cents per share to relieve indebtedness and enable further drilling on the company’s 870 acres in Rodeo Canyon. One year later, San Bernardino newspapers reported the company in trouble.

“This history of misadventure has not been pleasing to the stockholders of the Puente Crude Oil Company,” noted one article. “An auditing committee was appointed for the purpose of examining the books and accounts of the company,” it added.

Further reports in 1902 noted the company had issued no statements, “financial or otherwise,” for a year. Puente Crude Oil Company is absent from records thereafter.

South of Los Angeles, in Orange County, the Brea Museum and Heritage Center tells the story of the Olinda Oil Well No. 1 well of 1898 – one of many important California petroleum discoveries. Visit the Olinda Oil Museum and Trail at 4025 Santa Fe Road in Brea.

Much of Puente Oil’s former oil-producing land would later be managed by the Puente Hills Landfill Native Habitat Preservation Authority. In 2022, the Port of Los Angeles handled more than 220 million metric tons — 20 percent of all incoming cargo for the United States.

The stories of exploration and production (E&P) companies joining U.S. petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Los Angeles, California, Images of America (2001). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2001). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Puente Crude Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/puente-crude-oil-company. Last Updated: January 30, 2025. Original Published Date: July 2, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 2, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Three petroleum exploration companies risked everything on one well in their gamble to to find an Oregon oilfield.

The lure of petroleum wealth invited speculators practically since the first U.S. oil well of 1859 in Pennsylvania. Exploratory wells especially have remained a high-risk investment since almost nine out of ten of these “wildcat” wells fail to produce commercial amounts of oil.

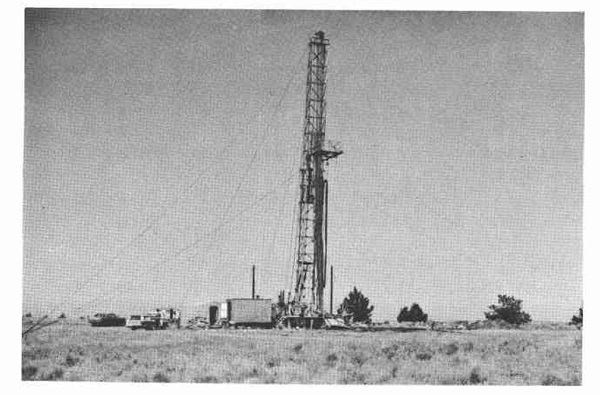

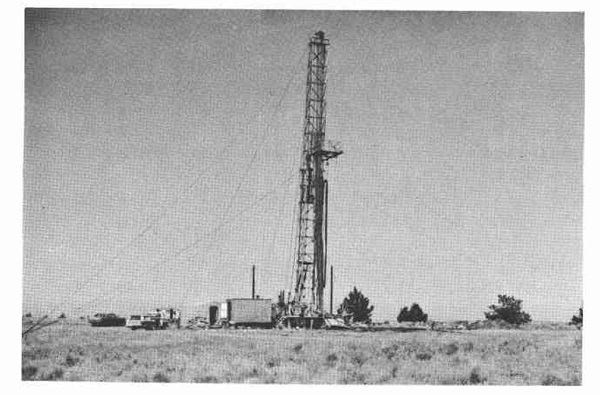

The Morrow No. 1 well, an ill-fated wildcat well first drilled in 1952 in Jefferson County, Oregon. Photo courtesy Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, “The Ore Bin,” Vol. 32, No.1, January 1970.

With under-capitalized operations turning to public sales of stock to raise money, many small ventures have been forced to bet everything on drilling a first successful well to have a chance at a second. Drilling a producing well can bring some wealth, but a “dry hole” brings bankruptcy.

And so it was in the 1950s on a remote hillside in Jefferson County, Oregon, where three companies searched for riches from the same well.

Northwestern Oils Inc.

The first of these three Oregon wildcatters, Northwestern Oils, incorporated in 1951 with $1 million capitalization in order to “carry on business of mining and drilling for oil.”

With offices in Reno, Nevada, in early 1952 Northwestern Oils began drilling a test well about eight miles southeast of Madras, Oregon. Using a cable-tool drilling rig (see Making Hole – Drilling Technology), drillers reached a depth of 3,300 feet on the Baycreek anticline before work was suspended because of “lost circulation troubles.”

Circulation troubles continued with the Morrow No. 1 well – also known as the Morrow Ranch well – in Jefferson County (Section 18, Township 12 South, range 15 East). By March 1956, with no money and no additional drilling possible, Northwestern Oils’ assets were “seized for non-payment of delinquent internal revenue taxes due from the corporation” and auctioned off at the Jefferson County courthouse.

Central Oils Inc.

Central Oils (Seattle) also was formed in 1956. With plans to join the other rare Oregon wildcatters, the company registered with the Security and Exchange Commission on July 30, 1958. It sought to sell one million shares of stock to the public at 10 cents a share. Proceeds would finance leasing and drilling, just like Northwestern Oils.

Central Oils received a permit to deepen Northwestern Oils’ old Morrow Ranch well in 1966 and planned to continue drilling with a cable-tool rig. Nothing happened.

“Commencement of this venture has been delayed until the spring of 1967,” one newspaper reported. But Central Oils had run afoul of the SEC. Oregon regulators recorded the well abandoned as of September 12, 1967, and Central Oils “out of business; no assets.”

Robert F. Harrison

In May 1968, Robert F. Harrison and his associates took over the same well — this time with plans to deepen it to more than 5,000 feet. But two years later the drilling effort was still stuck at a depth of 3,300 feet. Desperate, Harrison tried to clear the borehole by applying technologies for Fishing in Petroleum Wells.

On February 2, 1971, an intra-office report noted that R.F. Harrison “will abandon as soon as weather permits,” never having exceeded the original Northwestern Oils total depth of 3,300 feet. It would be a dry hole.

Harrison finally plugged and abandoned the Morrow No. 1 well as of October 12, 1971. Oregon’s Department of Geology and Mineral Industries has identified the stubborn nonproducer as well number 36-031-00003. There has never been a successful oil well drilled in Oregon.

America’s first dry hole was drilled in 1859 by John Grandin of Pennsylvania – near and just a few days after the first commercial discovery. In 2014, U.S. oil wells produced more than 8.7 million barrels of oil every day, according to the Energy Information Administration.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

______________________

Recommended Reading: Oil on the Brain: Petroleum’s Long, Strange Trip to Your Tank (2008);The Greatest Gamblers: The Epic of American Oil Exploration

(2008);The Greatest Gamblers: The Epic of American Oil Exploration (1979).

(1979).

Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oregon Wildcatters.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/oregon-wildcatters. Last Updated: February 26, 2025. Original Published Date: January 29, 2016.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 10, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

He was a controversial North Pole visitor whose fraudulent claims were part of failed oil company ventures, a mail fraud conviction, and jail time.

Arctic explorer Dr. Frederick Albert Cook in 1908 made the widely accepted claim to have reached the North Pole after an arduous journey. He became a celebrity after accounts of his feat appeared in newspapers. Cook’s near approach to the pole would be erased in less than a year when Admiral Robert E. Peary made a scientifically documented journey to achieve the milestone.

In 1909, a special commission at the University of Copenhagen investigated Cook’s conclusion that he had reached the pole before Peary. After examining Cook’s records, the commission on December 21, 1909, found no evidence Cook had reached the pole. The U.S. Congress formally recognized Peary’s claim in 1911.

Cook would spend years defending his claim, despite the lack of navigation evidence. Then he got into the oil business.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Sep 22, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

Learning hard lessons about wasteful overproduction and depleted reservoir pressures.

The discovery of oil along a small creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in August 1859 launched the American petroleum industry. Drilled just 69.5 feet deep at Oil Creek by former railroad conductor Edwin L. Drake, the well produced oil that could be refined into an inexpensive lamp fuel, kerosene.

Drake, who pioneered drilling technology, borrowed a local kitchen water pump to fill the first oil barrels. Early oil production from his and other northwestern Pennsylvania wells brought new refineries to Oil City and Pittsburgh on the Allegheny River.

Four acres close to the Sherman well sold for $220,000 as venture oil capitalists, entrepreneurs, and speculators tried their luck in the newly created petroleum industry.

Demand for kerosene quickly outpaced the inexpensive but volatile lamp fuel camphene. Kerosene also replaced expensive whale oil. A typical four-year whaling voyage returned with 40,000 gallons; New oilfields produced 10 million gallons of kerosene in 1860 alone.

Edwin Drake’s well, drilled for the first U.S. oil company established by George Bissell, brought the country’s first drilling boom as entrepreneurs rushed in. Farmers who leased their land were among the first to benefit.

“Oil Creek was soon taken up and within a relatively short time, the entire valley as far back as into the hillsides, had been leased or purchased,” author Paul Gibbons noted.

With the science of petroleum geology yet to debut, early oil explorers searched near oil seeps and the “rich territory was limited to flats along the streams,” Gibbons added. Natural gas discoveries would later arrive to the benefit of Pittsburgh industries.

Sherman Well of 1861

J.T. Foster’s farm on Pioneer Run hillside off Oil Creek was in “the dry diggings” where few were willing to gamble. Nonetheless, newly minted oil operators gathered investors to try to find oil. Capital was hard to come by.

On the 200-acre Foster farm, one struggling and almost cashless outfit had to trade a one-sixteenth interest for $80 and an old shotgun to continue drilling on its Sherman well.

Drilling along Oil Creek continued undiminished, but in September 1861 on the Funk farm, the Empire well began flowing a river of oil under its own pressure. They called it a “fountain well.” Some said it initially produced 2,000 barrels of oil a day. Other successful wells followed.

Back on the Foster farm lease, the Sherman well (saved earlier for $80 and a shotgun) in March 1862 was completed as the “best single strike of the year,” despite being “above all the other flowing wells” according to the Hornellsville Tribune. Leases became highly prized and, as historian Terence Daintith observed, “subleasing was also a money machine.”

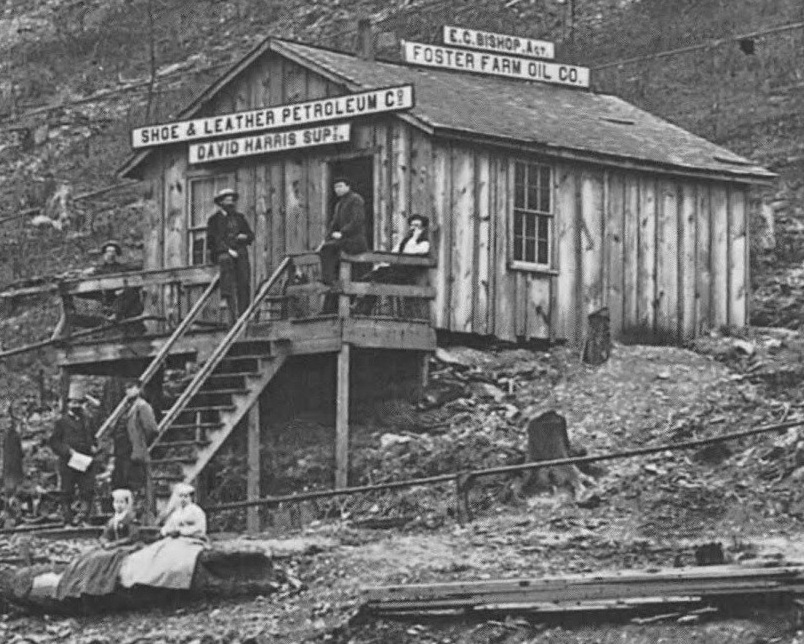

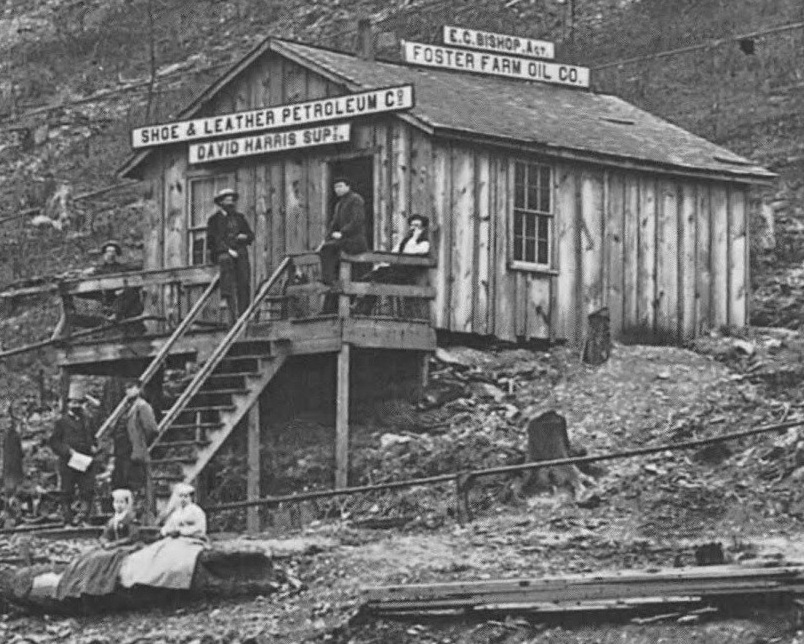

Oilfield offices of the Shoe & Leather Petroleum company, David Harris Supply Company, and the Foster Farm Oil Company, which drilled an 1866 well that produced 300 barrels of oil.

The Venango Citizen reported, “Territory along the river above and below Franklin has been changing hands at high figures, and preparations are being made for active work.”

Just four acres close to the Sherman well sold for $220,000 as venture capitalists, entrepreneurs, and speculators tried their luck in the newly created petroleum industry. The Foster Farm Oil Company and the Shoe & Leather Petroleum Company were among many corporations formed to exploit exploration opportunities.

Foster Farm Oil Company

Foster Farm Oil Company incorporated in February 1865. Based in Philadelphia and capitalized at $1.5 million, the company offered 150,000 shares to the public. “The Foster Farm is owned by a company of ten gentlemen, and is known as the Foster Farm Oil Company,” reported the The Titusville Morning Herald. E.C. Bishop (Elisa Chapman ) was principal owner as well as one time general agent, treasurer, and superintendent.

The new company secured acreage on the Foster farm that already had 12 wells pumping 100 barrels of oil a day. Foster leased acreage in small tracts to several new companies vying for closest proximity to known producers. Oil prices had always fluctuated wildly, but a standard 42-gallon barrel of crude oil sold in 1865 for about $6.50, including a Civil War excise tax of $1 per barrel.

Foster Farm Oil Company continued drilling and subleasing small tracts. In April 1866, it drilled a well producing 300 barrels of oil a day from 612 feet deep. Then a second well produced at 310 barrels, a third at 100, and another at 350 barrels of oil a day. In 1867, Foster Farm Oil Company sold 1,000 barrels of oil at $2.10 each.

All over the Pioneer Run hillside, wooden derricks with steam engines pumped away even as overproduction drained the oilfield. Margins disappeared and companies began to fail.

Foster Farm Oil Company’s fortunes faded, as did the value of its stock. In 1869, total U.S. oil production topped 4 million barrels and oversupply drove many out of business. After 10 years in the oil patch, Elisha C. Foster departed to enter the banking business in Connecticut.

By 1871, shares of Foster Farm Oil were being auctioned off along with other “Stocks, Loans, etc.” The following year, 5,000 shares of Foster Farm Oil Company were offered at 11 cents a share. Litigation began to overtake the failing company in 1873; it would continue long after the drilling boom had moved on, finally being settled by the Connecticut Superior Court in 1886.

Shoe & Leather Petroleum

Shoe & Leather Petroleum Company incorporated in New York City in March 1865 to join the Pennsylvania oil rush. The company initially capitalized at $400,000, later reduced to $160,000. “Until the spring of 1865, the Foster Farm, Pioneer Run and vicinity were considered dry territory. Through the exertions of Mr. David Harris of this city, the Shoe & Leather Petroleum was formed,” reported the Titusville Morning Herald.

The company leased six acres on the Foster farm, then subleased them into 11 smaller tracts – the kind sought by smaller, speculative operations. “Substantial leaseholders could milk their leases by subleasing small lots for large premiums and high royalties,” historian Daintith later noted. “Far more money could be made this way than by actual production.”

By 1867, Shoe & Leather Petroleum had five producing wells, on five different tracts, with five different operators, yielding about 350 barrels of oil a day. But frantic production at Pioneer Run and Oil Creek, compelled land owners above oil reserves to drill, “regardless of price or market demand, in order to prevent his neighbor from draining his reserves.”

This traditional “law of capture” rendered an oily landscape thick with derricks, according to local accounts.

Overproduction and waste depleted reservoir pressures. Wells were pumped dry. Triumph Hill, and Pithole and other examples reinforced the precedent of oil discovery leading to drilling boom, and then to inevitable bust. By 1902, United States Investor reported Shoe Leather & Petroleum Company had “disappeared” and concluded, “The supposition is that the company has gone out of existence.”

In 1904, Smythe’s Directory of Obsolete American Securities and Corporations described Shoe & Leather Petroleum, “Extinct. Stock worthless.”

The stories of exploration and production companies can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania (2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Early Wells of Oil Creek.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/early-wells-of-oil-creek. Last Updated: November 1, 2024. Original Published Date: December 22, 2018.

(2001). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.