Chicago business sought risky shale opportunities during WWI.

At the end of the 20th century, record-breaking petroleum production from shale oil grew thanks to drilling and production technologies that produced from low permeability “tight oil” formations. But a century ago, the shale was an unconventional resource mined, crushed and transported to a retorting facility.

Mining shale began as an extraction process that converted organic matter within the rock (kerogen) into synthetic oil and gas, which could be used as a fuel or upgraded for an oil refinery feedstock.

The strategic importance of America’s mined shale production led to establishment of the Naval Petroleum and Oil Shale Reserves in 1912, “to insulate the United States from foreign dependency on oil during times of war.”

Commissioned in 1914 with coal-powered boilers, the battleship USS Texas was converted to use fuel oil in 1925. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Meanwhile, fuel oil also began replacing coal in U.S. warships (See Petroleum and Sea Power), as World War I erupted in Europe. After more than three years of neutrality, America entered the war on April 2, 1917.

Recognizing wartime demand for oil, Van H. Manning, director, U.S. Bureau of Mines, declared, “We have as yet untouched our great reserves of shale that contain oil…and are conservatively estimated to contain many times the amount of oil that has been or will have been produced from all the porous formations in this country.”

Central Oil Shale Refining Company formed with $500,000 capitalization and set up offices in Chicago. The venture saw a financial opportunity in mining shale and secured leases on 480 acres in Garfield County, Colorado, an area with known deposits.

Central Oil Shale Refining also leased a total of about 5,000 acres in Kentucky, Kansas, and Texas. These investments were a gamble on the margins of supply and demand.

Despite the risks, Central Oil Shale Refining presented “Expert Information on Oil Shale” to stockholders and potential investors at Chicago’s Palmer House hotel. Company executives promoted the mining and distillation of Colorado oil shales as an opportunity not to be missed. It helped that publications like Oil Field Engineering (December 1917) proclaimed shales as “A New Source of Gasoline.”

Shale Business Model

Oil shale operator Joseph Bellis presented a business model to the Palmer House audience, describing oil shale production process and economics. Bellis, a veteran of Colorado shale mining in the Piceance Creek Basin, later published a paper in the Colorado School of Mines’ quarterly magazine.

The paper may have helped Central Oil Shale Refining stock sales, but the company’s trajectory had already been determined on a farm near Ranger, Texas.

Concerns about U.S. wartime oil supplies declined — along with oil prices — soon after an October 17, 1917, gusher halfway between Abilene and Dallas. Still annually celebrated by area residents, “Roaring Ranger” J. McCleskey No. 1 well produced 1,600 barrels of oil a day. Other wells in the oilfield would yield up to 10,000 barrels of oil daily.

The North Texas drilling boom opened giant fields near Desdemona and Breckenridge (Conrad Hilton would buy his first hotel in Cisco). An even bigger oilfield was found in 1918 at Burkburnett, near Wichita Falls. With suddenly abundant supplies, oil sold for less than $2 per barrel — five cents a gallon.

Central Oil Shale Refining was in deep trouble. Even if every ton mined resulted in 50 gallons of oil, it would take more than 1,300 tons of shale every day to match the McCleskey’s well production alone. The numbers didn’t work and debts needed to be paid.

In one last effort to survive, Central Oil Shale Refining reorganized with the same officers, moved its offices, and subtly changed its name to Central Oil Shale and Refining Company. The new company quickly failed, leaving a brief shadow in financial records.

Another example of producing commercial quantities of petroleum from shale can be found in Ute Oil Company – Oil Shale Pioneer. By the 1980s, new technologies revolutionized petroleum production from low-permeability shales — especially for natural gas.

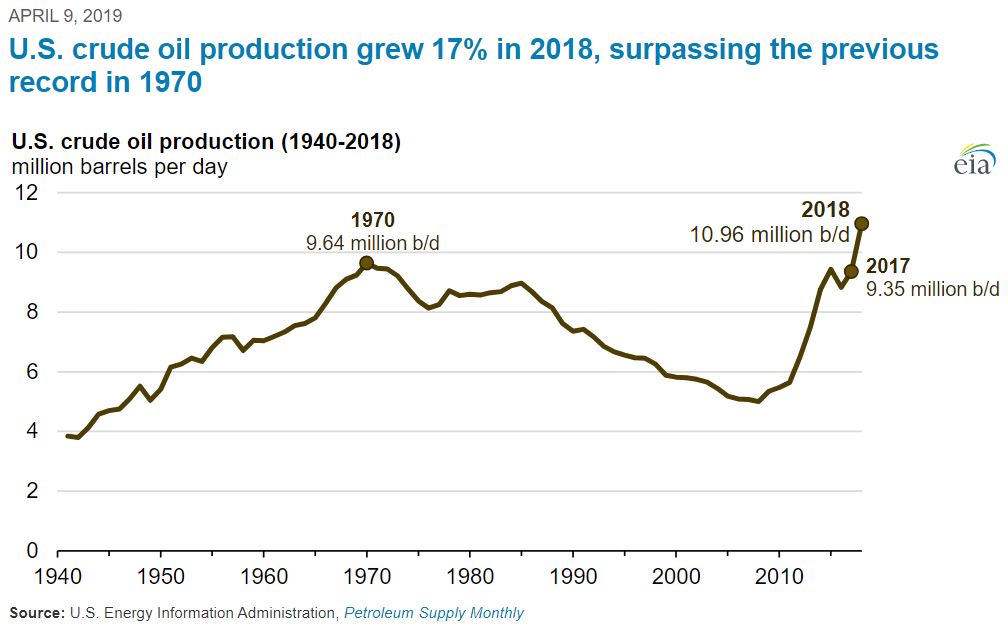

Annual U.S. crude oil production reached a record level of 10.96 million barrels per day in 2018, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Although geologists had known of the potential of drilling in these “tight oil” formations, only one percent of U.S. natural gas production came from shale as late as 2000. But by applying horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing techniques, in 2010 shale gas accounted for more than 20 percent of U.S. natural gas production, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Central Oil Shale Refining Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https:https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/central-oil-shale-refining-company. Last Updated: March 31, 2024. Original Published Date: April 1, 2019.