East Texas Oilfield Discovery

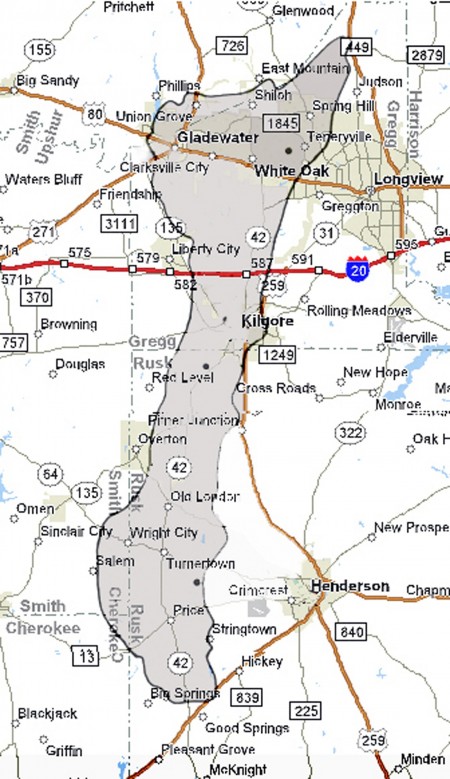

A 1930 wildcat well and two others miles away revealed the largest oilfield in the lower 48 states.

The East Texas oilfield — one of the greatest petroleum discoveries in United States history — arrived during the Great Depression.

With a crowd of more than 4,000 landowners, leaseholders, stockholders, creditors, and others gathered for the spectacle, the Daisy Bradford No. 3 well erupted a column of oil on a farm near Kilgore, Texas, on October 3, 1930.

Incredible to most geologists, another wildcat well 10 miles to the north — the Lou Della Crim No. 1 well, drilled by Malcolm Crim on his mother’s farm — began flowing on December 28, 1930. A month later and 15 miles north of that well, a third, the Lathrop No. 1 well, drilled by W.A. “Monty” Moncrief, delivered another gusher.

At first, the great distance between these “black gold” discoveries convinced geologists — and virtually all of the major oil companies — that the wildcat wells had found separate oilfields.

However, to the delight of many small, struggling farmers who owned the land, it finally became apparent that the three wells were all part of one giant oilfield.

H.L. Hunt and Oklahoma Wildcatters

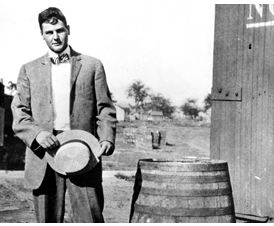

In 1905, when Haroldson Lafayette “H.L.” Hunt was just 16 years old, he left his Illinois farm family and headed west. Along the way, he worked as a dishwasher, mule team driver, logger, and farmhand — and even tried out for semi-pro baseball (also see Oilfield of Dreams — Gassers, Oilers and Drillers).

During his travels, young H.L. Hunt learned to gamble and played cards in bunkhouses, hobo camps, and saloons. But his life changed when an Arkansas wildcat well, the Busey-Armstrong No. 1, erupted oil on January 10, 1921. Hunt joined the speculative rush and drilling frenzy that followed. He began with $50 in his pocket.

The Arkansas oilfield discovery catapulted the population of El Dorado from 4,000 to over 25,000 (learn more in First Arkansas Oil Wells).

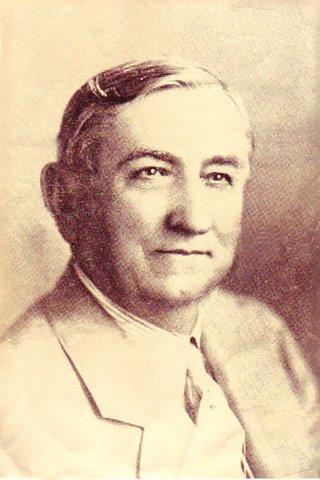

While Hunt was pursuing oil in Arkansas, an unlikely pair was doing the same in Oklahoma. Sixty-five-year-old Columbus Marion Joiner was a former lawyer and Tennessee legislator who had spent years making a living as an oil lease broker in Oklahoma. He had lost a $200,000 fortune in the financial panic of 1907 — and began pursuing the wealth a successful wildcatter and promoter might find.

A friend of Joiner, Joseph Idelbert Durham, had studied medicine and worked as a government chemist in the Idaho gold rush. Durham had also prospected for gold in the Yukon and Mexico before peddling patent oil medicines in “Dr. Alonzo Durham’s Great Medicine Show.”

Taking the name “A.D. Lloyd,” Durham proclaimed, “I’m not a professional geologist…but I’ve studied the earth more and know more about it than any professional geologist now alive will ever know.”

Joiner believed in “Doc” Lloyd, and his confidence was reinforced when Lloyd accurately located the rich Seminole oilfield. Joiner drilled to within 200 feet of discovering this previously untapped reserve — but stopped short when his money ran out. Empire Gas & Fuel Company brought in the field’s discovery well on a nearby lease.

After a similar near miss in Oklahoma’s Cement field and a stretch of bad luck, the broke but optimistic Joiner headed to Dallas, where oilmen and oil money were plentiful. Meanwhile, A.D. Lloyd was off to Mexico, promoting new oil ventures.

Back in the Oil Business: H.L. Hunt, Inc.

H.L. Hunt’s success in Arkansas enabled him to investigate other investment possibilities, and with El Dorado oilfield production diminishing, he was lured to Florida real estate. He sold his interests to the Louisiana Oil and Refining Company, retaining a few wells in the El Dorado and Smackover fields.

Hunt ultimately abandoned the Florida real estate market and returned to Arkansas, where in 1934 he formed H.L. Hunt, Inc. He was back in the oil business, the no-limit game he loved. Hunt traveled to Shreveport, Louisiana, and checked into the Washington-Youree Hotel, where the marble lobby hosted crowds of competing oil operators, promoters, and “lease hounds” — all looking for an edge in the high-risk world of petroleum exploration.

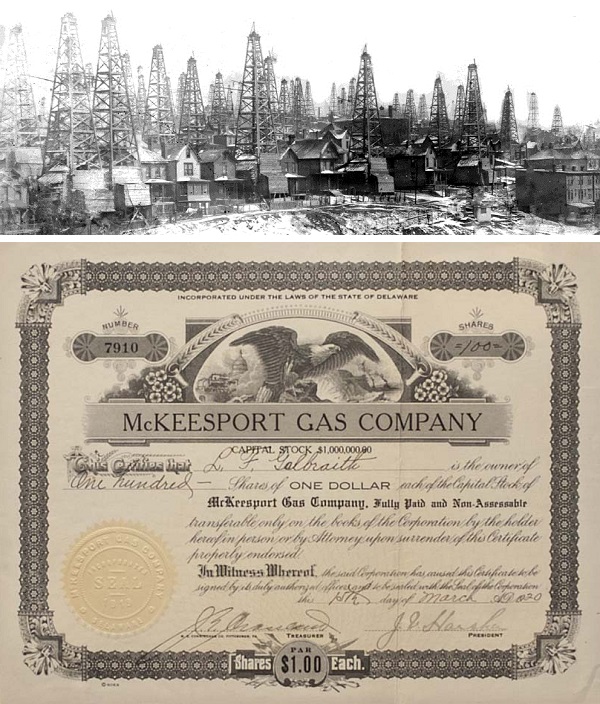

Speculators and promoters often profited where the true wildcatters could not. Not far to the west of Shreveport, Rusk County in northeastern Texas had seen its share of lease trading, despite the widely held conviction that there was no oil to be found there.

Geologists from major oil companies found no petroleum-rich salt domes (as in the 1901 Spindletop gusher at Beaumont to the south), anticlines, or other indications of oil. Seventeen wildcat wells had been dry holes.

“Dad” and “Doc” in Rusk County

Columbus Marion Joiner was undeterred. In 1927, he was 66 years old. He had just $45 in his pocket when he left Dallas to pursue opportunities in Rusk County. To poor farmers scratching out a living on drought-tormented land, Joiner seemed larger than life — a Bible-quoting genuine oil entrepreneur from Dallas who neither drank, smoked, nor cursed.

Within a few months, the affable but shrewd Joiner had acquired leases on several thousand acres and resumed his collaboration with A.D. “Doc” Lloyd.

Joiner formed a “Syndicate” from 500 of his lease block acres and began selling one-acre interest certificates to anyone who could scrape together $25. Joiner could be quite charming to the ladies and persuasive to gentlemen.

Small investments from hopeful Rusk County farmers and merchants provided Joiner just enough month-to-month money to get by and sometimes pay on his considerable lease rental debt. Promoting oil certificates in an area largely dismissed by professionals called for a slick pitch, and Joiner’s self-taught geologist friend, “Doc” Lloyd, could help.

While Humble Oil Company geologists and geophysicists were reporting that Rusk County offered no possibilities, Joiner was mailing his own report to potential investors: “Geological, Topographical and Petroliferous Survey, Portion of Rusk County, Texas, Made for C.M. Joiner by A.D. Lloyd, Geologist and Petroleum Engineer.”

Using clear and correct scientific terminology, “Doc” Lloyd’s document described Rusk County anticlines, faults, and a salt dome — all geologic features associated with substantial oil deposits and all completely fictitious. Equally imaginary were the “Yegua and Cook Mountain formations” and the thousands of seismographic registrations ostensibly recorded.

The impressive-looking but fabricated report was accompanied by a map depicting a “salt dome” and a fault running squarely through the widow Daisy Bradford’s farm, the exact site of the 500-acre Syndicate lease block that “Dad” Joiner was promoting.

Dry Hole, Dry Hole

“Doc” Lloyd’s assessment had the desired effect, and the increased sales of certificates enabled Joiner to patch together a rusty, worn-out rig and begin drilling the Daisy Bradford No. 1 in August 1927.

To sustain operations and in pursuit of new investors, Joiner created more syndicates and sold far more certificates than he could possibly redeem, in one case selling the same certificate to eleven different investors. This didn’t present a problem unless Joiner actually brought in a producing well, but if he did, finding oil was the kind of “problem” wildcatters wished for.

In February 1928, the Daisy Bradford No. 1 well failed at 1,098 feet when the drill pipe became irretrievably stuck. Joiner continued overselling certificates to finance drilling.

In March 1929, his Daisy Bradford No. 2 suffered a like fate at 2,518 feet — far deeper than the hodgepodge of old equipment was thought capable.

Haroldson Lafayette “H. L.” Hunt (third from right) is a former dishwasher, mule team driver, logger, farmhand, and semi-pro baseball tryout. C. M. “Dad” Joiner (third from left) shakes the hand of geologist A. D. “Doc” Lloyd at the 1930 discovery well of the East Texas oilfield. Recognizing the significance of the discovery before his competitors, H. L. Hunt will move quickly — and take significant risk — by purchasing the discovery well and nearby leases from Joiner.

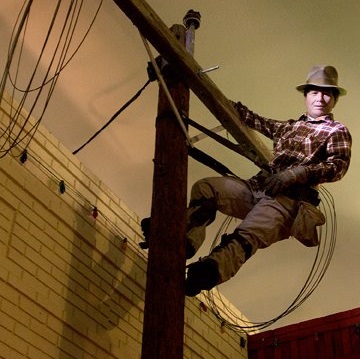

Daisy Bradford No. 3 was spudded just 375 feet from the failed second attempt at a site determined when broken equipment prevented moving any farther. Before long, Joiner’s “poor boy” operation was down to burning used tires in the old boiler to gain a few pounds of steam pressure and drill a few feet at a time.

In September 1930, Hunt and Joiner met for the first time when Daisy Bradford’s brother invited Hunt to observe a drill stem test at Joiner’s third well (drill stem tests can determine if oil is present in a formation and the rate at which it can be produced).

Hunt — always on the lookout for new opportunities — drove to the site on the widow Bradford farm with his friend from El Dorado, merchant and clothier P.G. “Pete” Lake.

The Woodbine Sand

The well test was done on September 3, 1930. When the drill stem test brought a surge of mud, oil, and natural gas, Hunt was impressed. He raised enough money to lease three tracts to the east and one to the south of Joiner’s well as the news spread and the scramble for a piece of the action began. The Woodbine sand formation will make petroleum history.

In two weeks, more than 2,000 land deals were recorded; two weeks later, Daisy Bradford No. 3 blew in as a gusher in front of about 5,000 spectators who cheered madly, celebrated their newfound fortunes, and congratulated “Dad” Joiner. It wasn’t long, however, before the greatly oversold Syndicate certificates created a convoluted legal nightmare of immense proportions for the now famous “Dad” Joiner.

On the 31st of October, a Dallas court put Joiner’s holdings into receivership. Seventy-year-old Columbus Marion Joiner took refuge in a Dallas hotel as swarms of claimants and creditors looked for him.

Following the drill stem test and aware of previous dry holes drilled to the east, H.L. Hunt became convinced that a substantial oilfield lay to the west. His conviction was reinforced when dry holes were drilled both southeast and northeast of Daisy Bradford No. 3, abruptly chilling the lease market.

Meanwhile, just a mile west of Joiner’s find and surrounded by his leases, Deep Rock Oil Company was drilling a test well on the Claude Ashby farm. Hunt believed that if this well came in, it would confirm that Daisy Bradford No. 3 was part of a much larger oilfield. A dry hole would prove the major oil companies’ belief that Joiner’s Woodbine sand reservoir was a fluke.

Hunt assigned three oil scouts to closely monitor and report to him on the progress of the Ashby No. 1 well. Since his own credit was exhausted, he tried to interest Deep Rock and others in deals to buy out Joiner, but Daisy Bradford No. 3 was by then flowing intermittently. It would yield only about 200 barrels of oil and stop altogether for an agonizing 18 to 20 hours before resuming.

Hunt remained convinced Joiner’s contested leases sat atop an oilfield, but just how big an oilfield was beyond Hunt’s or anybody else’s imagination. He later wrote, “Joiner was a true wildcatter and was much more interested in drilling wildcat wells than developing proven or semi-proven oil acreage. He was becoming weary of all the carrying on which was being made against him.”

Hunt’s “Business Coup”

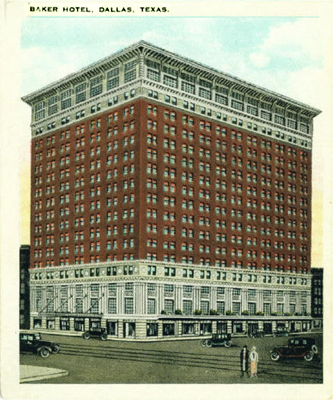

Hunt borrowed $30,000 from his old El Dorado clothier friend, P.G. Lake, and set about to convince the harried and hiding “Dad” Joiner to sell. They met in Dallas’ Baker Hotel on November 25-26, 1930, while Hunt’s scouts continued to watch the Deep Rock well’s progress.

At about 8:30 p.m. on November 26, Hunt’s scouts reported that the Deep Rock well had found the oil-rich Woodbine sand, confirming his belief in the oilfield. Four hours later, Joiner sold all his holdings (including about 5,000 leased acres) to Hunt for $1,335,000, including all the $30,000 in cash Hunt had borrowed. It was far more money than Joiner had ever seen and provided him a way out of the legal mess of oversold certificates and competing claims.

It was for Hunt — as he later described — his “greatest business coup,” despite the 300 lawsuits that followed. As presiding District Judge R.T. Brown said, “If you want a successful gathering of long-lost kinfolks, just manage to find oil on the old homestead. They will come out from under logs, down trees, from out of the blue, and down every road and byway, but they’ll get there — even some nobody ever suspected were kinfolks.”

In the 10 years of litigation that followed, Hunt sustained every title. Eighteen days after his deal with Joiner, Deep Rock’s Ashby No. 1 came in at 3,000 barrels of oil a day.

The “Black Giant”

On a Sunday two weeks later, Lou Della Crim No. 1 came in 13 miles to the north, near Kilgore, Texas, flowing at over 22,000 barrels of oil a day. In January 1931, the similarly petroleum-rich Lathrop No. 1 well came in about 15 miles farther north, in Gregg County. Remarkably, the Ashby, Lou Della Crim, and Lathrop wells were all part of the same gigantic field, covering over 140,000 acres!

Hunt’s deal had put him in the midst of the unprecedented “Black Giant” known as the East Texas oilfield. In 1972, James A. Clark and Michel T. Halbouty published The Last Boom, noting, “The fortune Hunt built in East Texas served as the foundation for one much larger, for he could no more stop hunting for oil than could Joiner — and he seemed to find it as often as not.”

Production from the giant oilfield yielded five billion barrels of oil by 1980, and thanks to Dallas-based Hunt Oil Company, that was the year the East Texas Oil Museum opened at Kilgore College, not far from the Daisy Bradford No. 3 well.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Last Boom (1972);The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field and Oil Industry Skullduggery & Trivia (2003); The Big Rich: The Rise and Fall of the Greatest Texas Oil Fortunes (2009); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “East Texas Oilfield Discovery.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/east-texas-oilfield. Last Updated September 25, 2025. Original Published Date: October 22, 2012.