by Bruce Wells | Dec 3, 2024 | Petroleum Products

G.M. scientists discover the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead gasoline.

General Motors scientists in 1921 discovered the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead as an additive to gasoline. By 1923, many American motorists would be driving into service stations and saying, “Fill ‘er up with Ethyl.”

Early internal combustion engines often suffered from a severe “knocking,” the out-of-sequence detonation of the gasoline-air mixture in a cylinder. The constant shock added to exhaust valve wear and frequently damaged engines.

Automobiles powered with gasoline had been the least popular models at the November 1900 first U.S. auto Show in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

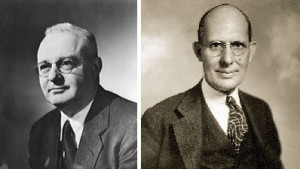

General Motors chemists Thomas Midgely Jr. and Charles F. Kettering tested many gasoline additives, including arsenic.

On December 9, 1921, after five years of lab work to find an additive to eliminate pre-ignition “knock” problems of gasoline, General Motors researchers Thomas Midgely Jr. and Charles Kettering discovered the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead.

Early experiments at GM examined the properties of knock suppressors such as bromine, iodine and tin — comparing these to new additives such as arsenic, sulfur, silicon and lead.

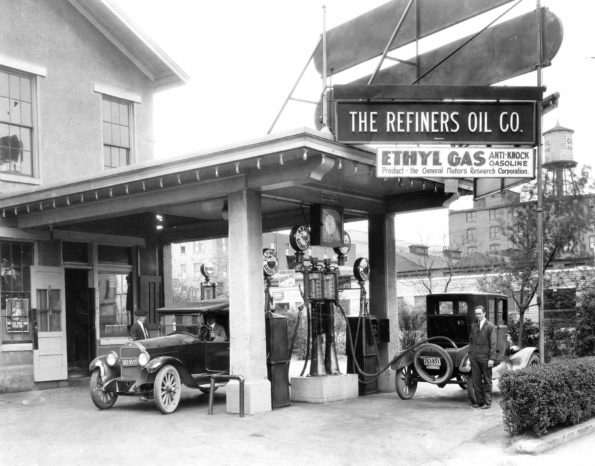

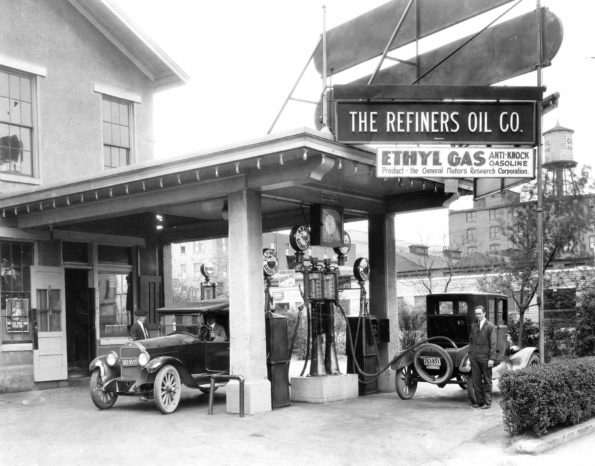

The world’s first anti-knock gasoline containing a tetra-ethyl lead compound went on sale at the Refiners Oil Company service station in Dayton, Ohio. A bolt on “Ethylizer” can be seem running vertically alongside the visible reservoir. Photo courtesy Kettering/GMI Alumni Foundation.

When the two chemists synthesized tetraethyl lead and tried it in their one-cylinder laboratory engine, the knocking abruptly disappeared. Fuel economy also improved. “Ethyl” vastly improved gasoline performance.

“Ethylizers” debut in Dayton

Although being diluted to a ratio of one part per thousand, the lead additive yielded gasoline without the loud, power-robbing knock. With other automotive scientists watching, the first car tank filled with leaded gas took place on February 2, 1923, at the Refiners Oil Company service station in Dayton, Ohio.

In the beginning, GM provided Refiners Oil Company and other service stations special equipment, simple bolt on adapters called “Ethylizers” to meter the proper proportion of the new additive.

“By the middle of this summer you will be able to purchase at approximately 30,000 filling stations in various parts of the country, a fluid that will double the efficiency of your automobile, eliminate the troublesome motor knock, and give you 100 percent greater mileage,” Popular Science Monthly reported in 1924.

By the late 1970s, public health concerns resulted in the phase-out of tetraethyl lead in gasoline, except for aviation fuel.

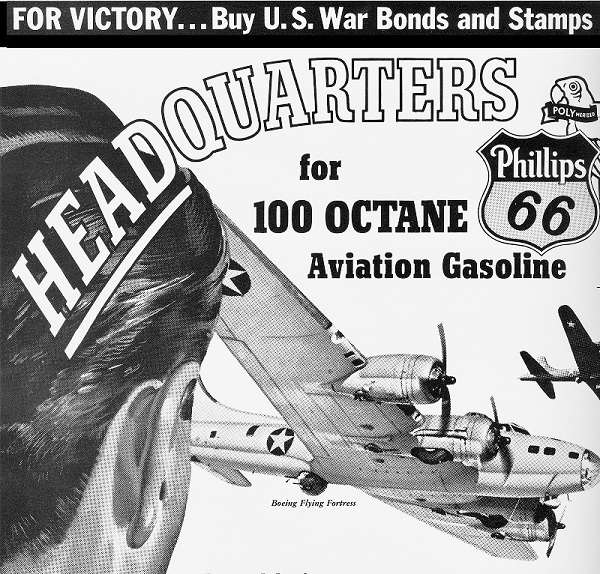

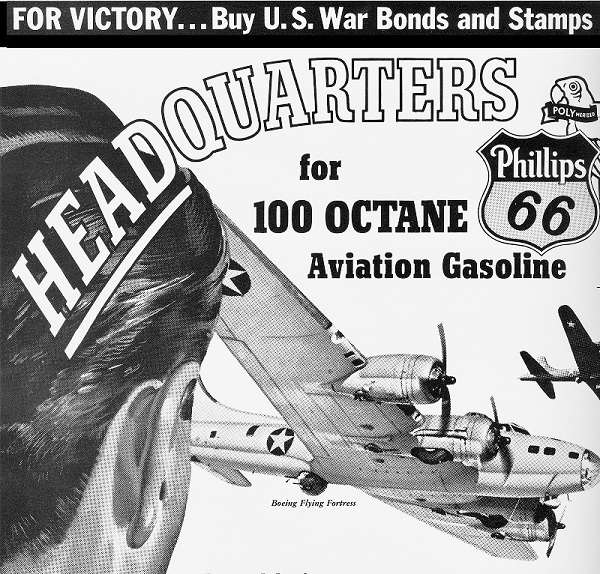

Anti-knock gasoline containing a tetraethyl lead compound also proved vital for aviation engines during World War II, even as danger from the lead content increasingly became apparent.

Powering Victory in World War II

Aviation fuel technology was still in its infancy in the 1930s. The properties of tetraethyl lead proved vital to the Allies during World War II. Advances in aviation fuel increased power and efficiency, resulting in the production of 100-octane aviation gasoline shortly before the war.

Phillips Petroleum – later ConocoPhillips – was involved early in aviation fuel research and had already provided high gravity gasoline for some of the first mail-carrying airplanes after World War I.

Phillips Petroleum produced tetraethyl leaded aviation fuels from high-quality oil found in Osage County, Oklahoma, oilfields.

Phillips Petroleum produced aviation fuels before it produced automotive fuels. The company’s gasoline came from the high-quality oil produced from Oklahoma’s Seminole oilfields and the 1917 Osage County oil boom.

Although the additive’s danger to public health was underestimated for decades, tetraethyl lead has remained an ingredient of 100 octane “avgas” for piston-engine aircraft.

Tetraethyl lead’s Deadly Side

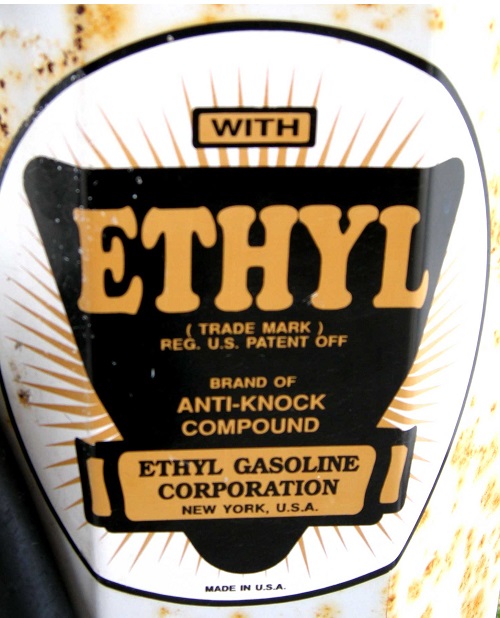

Leaded gasoline was extremely dangerous from the beginning, according Deborah Blum, a Pulitzer-Prize winning science writer. “GM and Standard Oil had formed a joint company to manufacture leaded gasoline, the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation,” she noted in a January 2013 article. Research focused solely on improving the formula, not on the danger of the lead additive.

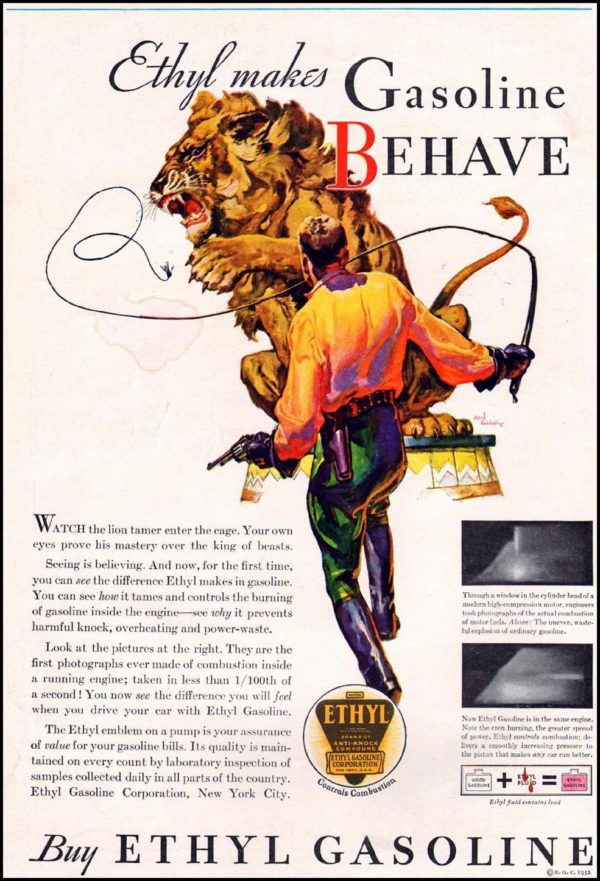

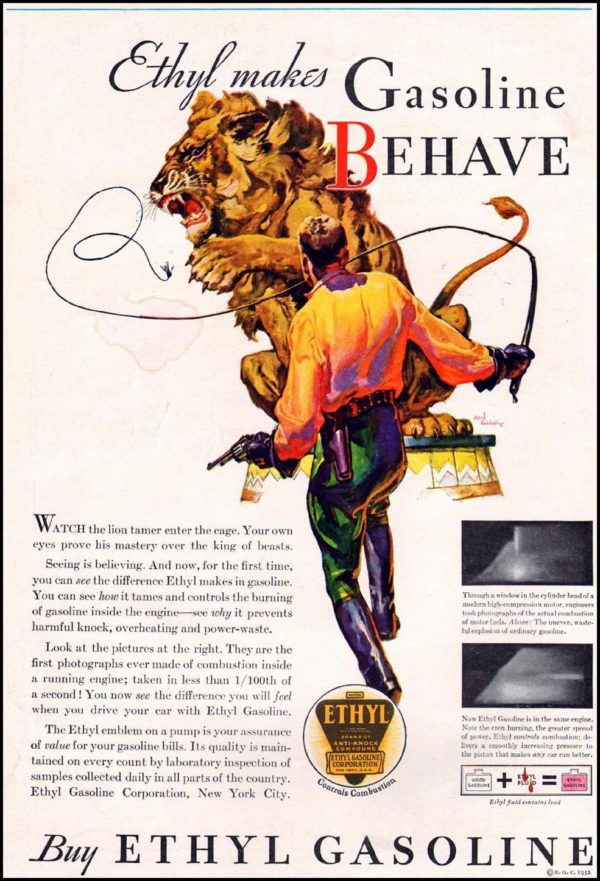

A 1932 magazine advertisement promoted the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation fuel additive as a way to improve high-compression engine performance.

“The companies disliked and frankly avoided the lead issue,” Blum wrote in “Looney Gas and Lead Poisoning: A Short, Sad History” at Wire.com. “They’d deliberately left the word out of their new company name to avoid its negative image.”

In 1924, dozens were sickened and five employees of the Standard Oil Refinery in Bayway, New Jersey, died after they handled the new gasoline additive.

By May 1925, the U.S. Surgeon General called a national tetraethyl lead conference, Blum reported, and an investigative task force was formed. Researchers concluded there was ”no reason to prohibit the sale of leaded gasoline” as long as workers were well protected during the manufacturing process.

So great was the additive’s potential to improve engine performance, the author notes, by 1926 the federal government approved continued production and sale of leaded gasoline. “It was some fifty years later – in 1986 – that the United States formally banned lead as a gasoline additive,” Blum added.

By the early 1950s, American geochemist Clair Patterson discovered the toxicity of tetraethyl lead; phase-out of its use in gasoline began in 1976 and was completed by 1986. In 1996, EPA Administrator Carol Browner declared, “The elimination of lead from gasoline is one of the great environmental achievements of all time.”

Learn more about high-octane aviation fuel in Flight of the Woolaroc.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: An Illustrated Guide to Gas Pumps (2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website, expand historical research, and extend public outreach. For annual sponsorship information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All right reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Ethyl Anti-Knock Gas.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/tetraethyl-lead-gasoline. Last Updated: December 3, 2024. Original Published Date: December 7, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 2, 2024 | Petroleum Products

Tinsmith recreated 19th-century whale oil, lard, camphene, and two-spouted burning fluid lamps.

Designed for different fuels, 19th-century lamps burned many fuels, including rapeseed oil, lard, whale oil, and camphene — the distilled spirits of turpentine. Another popular fuel was “burning fluid,” a volatile combination of distilled spirits of turpentine and alcohol with camphor oil added for aroma.

Until replaced by the safer lamp fuel kerosene, two-wicked burning-fluid lamps provided light for much of America.

The burning fluid mixture required a double burner but no chimney, according to Ron Miller, a self-taught tinsmith and “hands-on historian.” He became fascinated by the designs of these early illuminating lamps.

Jim Miller’s 19th century lamp tin recreations, left to right: a whale oil burner; an 1842 patented lard oil burner; a “Betty Lamp” fueled by fat; and a typical burning fluid two-spout lamp.

“This adventure has deepened my appreciation for past craftsmanship and the intelligence of common place things in early America,” explained Miller in his 2012 For the love of History blog. “Besides, now I have all this cool stuff to play (teach) with.”

The key to learning about early to mid-19th century oil lamps was to study their burners, Miller noted (see Camphene to Kerosene Lamps), adding, “each type of fuel needed a specific style of burner to give the best light.”

Although most of the fuels have become obsolete, Miller “wanted to faithfully replicate the burners, in order to understand how they evolved,” he said, adding, “For the time being, substitute fuels would have to do.”

Miller fashioned tin into period lamp designs, including one fueled by fat — a “Betty Lamp” that “has an ancestry extending clear back to the Romans but had been improved on over time.” He also recreated a whale oil lamp, circa 1850, and a patented lard oil burner of 1842 (the lard needed to be warmed, to improve its fluidity).

Miller also created a lard oil lamp using a burner patent from 1842.

“These tubes never extend down past the mounting plate and never have slots for wick adjustment. Apparently, any heat added to the fuel caused an accumulation of gases,” he noted. Most surviving original burners have little covers to snuff out the flame and keep the fuel from evaporating. Newspapers also reported the danger of flash fires during refueling.

“The style of lamp I chose to replicate is sometimes called a petticoat lamp by collectors for the flared shape of the base. Such lamps are often mislabeled as Whale Oil lamps but the difference is obvious once you know your burners,” Miller concluded about his replica.

“In case you wondered, my lamp burns modern lamp oil as I don’t need to kill myself in the pursuit of history,” the tinsmith added.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Oil Lamps The Kerosene Era In North America (1978). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1978). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Making a Two-Wick Lamp.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/two-wick-camphene-lamp. Last Updated: December 13, 2024. Original Published Date: March 11, 2018.

.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 12, 2024 | Petroleum Products

Making “wet gas” in early 20th century Oklahoma oilfields.

When Robert Galbreath and Frank Chesley completed their Ida Glenn No. 1 well on November 22, 1905, they revealed another giant oilfield south of Tulsa. The discovery well, drilled with cable-tool technology, struck oil-bearing sands at depth of only 1,450 feet. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jul 10, 2024 | Petroleum Products

Highly refined propellant began as “coal oil” for lamps.

A 19th-century petroleum product made America’s 1969 moon landing possible. On July 16, 1969, kerosene rocket fuel powered the first stage of the Saturn V of the Apollo 11 mission.

Four days after the Saturn V launched Apollo 11, astronaut Neil Armstrong announced, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” His achievement rested on new technologies – and tons of fuel first refined for lamps by a Canadian in 1848.

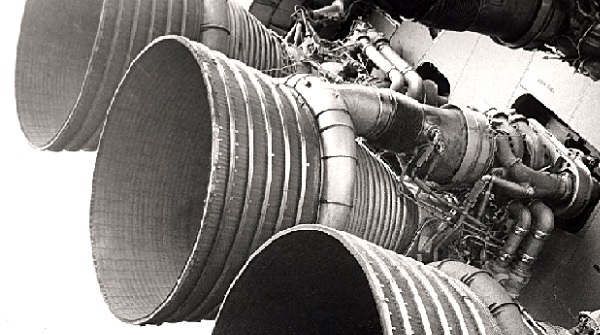

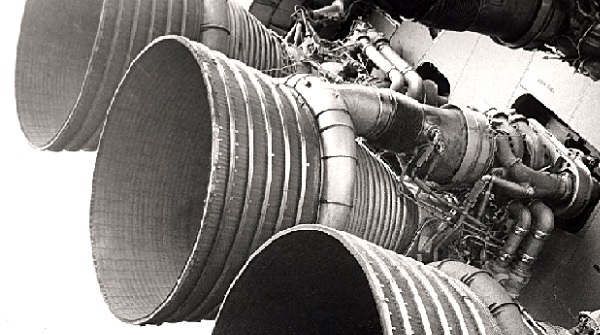

Powered by five first-stage engines fueled by “rocket grade” kerosene, the Saturn V was the tallest, heaviest and most powerful rocket ever built until the SpaceX Starship. Photos courtesy NASA.

During launch, five Rocketdyne F-1 engines of the massive Saturn V’s first stage burn “Rocket Grade Kerosene Propellant” at 2,230 gallons per second – generating almost eight million pounds of thrust.

The F-1 engines of the Saturn V first stage at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Photo courtesy NASA.

Saturn’s rocket fuel is highly refined kerosene RP-1 (Rocket Propellant-1 or Refined Petroleum-1) which, while conforming to stringent performance specifications, is essentially the same “coal oil” invented in the mid-19th century.

Canadian physician and geologist Abraham Gesner began refining an illuminating fuel from coal in 1846. “I have invented and discovered a new and useful manufacture or composition of matter, being a new liquid hydrocarbon, which I denominate Kerosene,” he noted in his patent.

The father of American rocketry, Robert Goddard, in 1926 used gasoline to fuel the world’s first liquid-fuel rocket, seen here in its launch stand. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

By 1850, Gesner had formed a company that installed lighting in the streets in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 1854, he established the North American Kerosene Gas Light Company at Long Island, New York.

Although he had coined the term kerosene from the Greek word keros (wax), because his fluid was extracted from coal, most consumers called it “coal oil” as often as they called it kerosene.

By the time of the first U.S. oil well drilled by Edwin Drake in 1859, a Yale scientist (hired by the well’s investors) reported oil to be an ideal source for making kerosene, far better than refined coal. Demand for kerosene refined from petroleum launched the nation’s exploration and production industry.

Electricity replaced kerosene lamps and gasoline dominated 20th century demand for transportation fuel, but kerosene remained as a powerful fuel choice.

Jet Cars

Nathan Ostrich built the first jet car in 1962 using an engine originally designed for the North American F-86 Sabre jet fighter. Powered by a General Electric J47 at Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats, his Flying Caduceus set a world record of more than 330 mph.

On November 7, 1965, California race car driver Art Arfons increased the land-speed record to 576.553 miles per hour on the famous one-mile strip. The Ohio drag racer’s home-made Green Monster was powered by JP-4 fuel (a 50-50 kerosene-gasoline blend), in an afterburner-equipped F-104 Starfighter turbojet jet engine.

A kerosene-gasoline blend powered the F-104 jet engine of the Green Monster to world records,.

Arfon set the world land-speed record three times between 1964 and 1965, in what became known as “The Bonneville Jet Wars.”

Record challenger Craig Breedlove’s Spirit of America Sonic 1 in 1965 used a jet engine from an F-4 Phantom II to defeat the Green Monster and set a record of 600.601 mph, which lasted until 1970, when the Blue Flame Natural Gas Rocket Car reached 630.388 mph.

Kerosene Rockets

Kerosene’s ease of storage and stable properties attracted early rocket scientists like America’s Robert H. Goddard and Germany’s Wernher von Braun. During World War II, kerosene-fueled Nazi Germany’s notorious V-2 ballistic missiles.

Decades of post-war rocket engine research and testing led to the Saturn V’s five Rocketdyne F-1 engines. The F-1 was the most powerful single-combustion chamber engines ever developed, according to David Woods, author of How Apollo Flew to the Moon, 2008.

The Rocketdyne F-1 engines, 19 feet tall with nozzles about 12 feet wide, include fuel pumps delivering 15,471 gallons of RP-1 per minute to their thrust chambers. The Saturn V’s upper stages burn highly volatile liquid hydrogen (and liquid oxygen in all three stages).

The five-engine main booster held 203,400 gallons of RP-1. After firing, the engines can empty the massive fuel tank in 165 seconds.

Kerosene fueled the Saturn V’s five main engines used for getting Apollo astronauts to the moon. NASA photo detail.

The Apollo 11 landing crowned liquid-rocket fuel research in America dating back to Goddard and his 1914 “Rocket Apparatus” powered by gasoline. In March 1926, Goddard launched the world’s first liquid-fuel rocket from his aunt’s farm in Auburn, Massachusetts.

Although gasoline will be replaced with other propellants, including the liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen used in the space shuttle’s external tank, RP-1 kerosene continues to fuel spaceflight.

Cheaper, easily stored at room temperature, and far less of an explosive hazard, the 19th-century petroleum product today fuels first-stage boosters for the Atlas, Delta II, Antares, and the latest SpaceX rockets. Reusable SpaceX Falcon 9 rockets have nine Merlin engines burning kerosene fuel and generating 1.7 million pounds of thrust.

Last launched in 1972, the Saturn V was the most powerful rocket ever built, until it was surpassed by SpaceX’s Starship — fueled by liquid oxygen and liquid methane.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles (2003). As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2003). As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves oil history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Kerosene Rocket Fuel.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:https://aoghs.org/products/kerosene-rocket-fuel. Last Updated: July 10, 2024. Original Published Date: July 12, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Jul 3, 2024 | Petroleum Products

How a petroleum product at bottom of the refining process improved American mobility.

As the U.S. centennial approached, President Ulysses S. Grant directed that Pennsylvania Avenue be paved with asphalt. By 1876, the president’s paving project using Trinidad asphalt covered about 54,000 square yards. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | May 27, 2024 | Petroleum Products

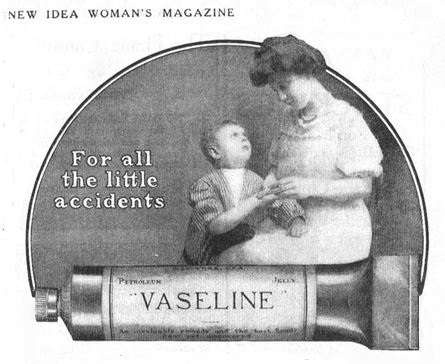

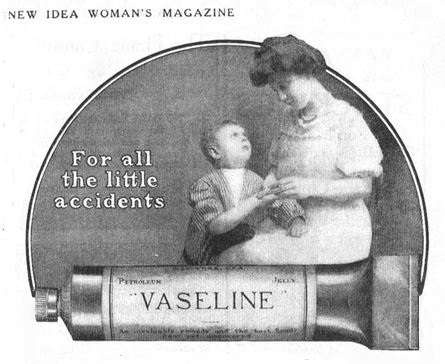

How oilfield paraffin created Vaseline — and Maybelline.

Few associate 1860s oil wells with women’s eyes, but they are fashionably related. From paraffin to Vaseline, this is the story of how the goop that accumulated around the sucker rods of America’s earliest oil wells made its way to eyelashes.

In 1865, a 22-year-old Robert Chesebrough left the prolific oilfields of Pithole and Titusville, Pennsylvania, to return to his Brooklyn, New York, laboratory. He carried samples of a waxy substance that clogged wellheads. He already had dabbled in the “coal oil” business with experiments on refinery processes.

Robert Chesebrough will find a way to purify the waxy paraffin-like substance that clogged oil wells in early Pennsylvania petroleum fields. Photo courtesy Unilever Corp.

Chesebrough’s laboratory expertise included distilling cannel coal into kerosene (coal oil), a lamp fuel in high demand among consumers. He also knew of the process for refining crude oil into a kerosene.

So, when Edwin L. Drake completed the first U.S. oil well in August 1859, Chesebrough was among those who rushed to Pennsylvania oilfields to make his fortune.

“Now commenced a scene of excitement beyond description,” reported Scientific American. “The Drake well was immediately thronged with visitors arriving from the surrounding country, and within two or three weeks thousands began to pour in from the neighboring States.”

Chesebrough was convinced he too could get rich from the “black gold” of Pennsylvania’s oilfields.

Oilfield Sucker Rod Wax

In the midst of the Venango County exploration and production chaos, the young chemist noted a waxy buildup often confounded drilling. This paraffin-like substance clogged the wellhead and drew curses from riggers who had to stop drilling to scrape it away.

Robert Chesebrough consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day and lived to be 96. This early bottle from the collection of the Drake Well Museum in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

The only virtue of this goopy oilfield “sucker rod wax” was as an immediately available first aid for the abrasions, burns, and other wounds routinely afflicting the crews.

Paraffin to Vaseline

Chesebrough abandoned his notion of drilling a gusher and returned to New York, where he worked in his laboratory to purify the troublesome sucker-rod wax, which he dubbed “petroleum jelly,” one of America’s earliest petroleum products.

By August 1865, Chesebrough had filed the first of several patents “for purifying petroleum or coal oils by filtration.”

The chemist experimented with the analgesic effects of his extract by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying the purified petroleum jelly. He also gave it to Brooklyn construction workers to treat their minor scratches and abrasions.

After refining oilfield wax, Chesebrough experimented by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying his petroleum balm.

On June 4, 1872, Chesebrough patented a new product that would endure to this day – “Vaseline.” His paraffin to Vaseline patent extolled new balm’s virtues as a leather treatment, lubricator, pomade, and balm for chapped hands. Chesebrough soon had a dozen wagons distributing the product around New York.

Customers used the “wonder jelly” creatively: treating cuts and bruises, removing stains from furniture, polishing wood surfaces, restoring leather, and preventing rust. Within 10 years, Americans were buying it at the rate of a jar a minute

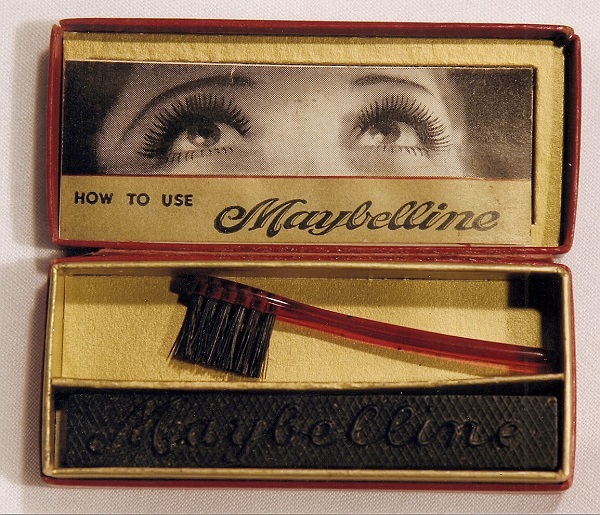

Women had once used toothpicks to mix lamp black with Vaseline. By 1917, Tom Williams was selling premixed “Lash-Brow-Ine” by mail-order. Photo courtesy Sharrie Williams.

An 1886 issue of Manufacture and Builder even reported, “French bakers are making large use of vaseline in cake and other pastry. Its advantage over lard or butter lies in the fact that, however stale the pastry may be, it will not become rancid.”

Flavor notwithstanding, Chesebrough himself consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day. He lived to be 96 years old. It was not long before thrifty young ladies found another use for Vaseline.

Mabel’s Eyelashes

As early as 1834, the popular book Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion had suggested alternatives to the practice of darkening eyelashes with elderberry juice or a mixture of frankincense, resin, and mastic.

“By holding a saucer over the flame of a lamp or candle, enough ‘lamp black’ can be collected for applying to the lashes with a camel-hair brush,” the book advised.

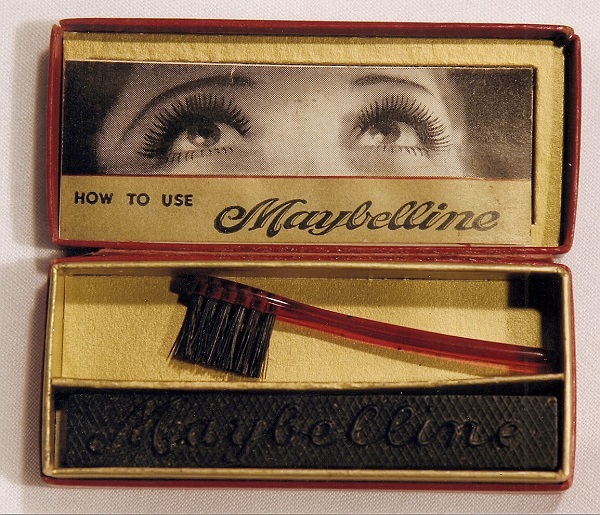

Chesebrough’s female customers found that mixing lamp black with Vaseline using a toothpick made an impromptu mascara. Some sources claim that Miss Mabel Williams in 1913 employed just such a concoction preparing for a date. Williams was dating Chet Hewes.

Women were using Vaseline to make mascara by 1915. Cosmetic industry giant Maybelline traces its roots to the petroleum product. “What a Difference Maybelline Does Make” magazine ad from 1937.

Perhaps using coal dust or some other readily available darkening agent, she applied the mixture to her eyelashes for a date. Her brother, Thomas Lyle Williams, was intrigued by her method and decided to add Vaseline in the mixture, noted a Maybelline company historian.

A more reliable version of the story — told by Williams’ grandniece Sharrie Williams — has Mabel demonstrating “a secret of the harem” for her brother.

“In 1915, when a kitchen stove fire singed his sister Mabel’s lashes and brows, Tom Lyle Williams watched in fascination as she performed what she called ‘a secret of the harem’ mixing petroleum jelly with coal dust and ash from a burnt cork and applying it to her lashes and brows,” Sharrie Williams explained in her 2007 book, The Maybelline Story and the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It.

“Mabel’s simple beauty trick ignited Tom’s imagination and he started what would become a billion-dollar business,” concluded Williams.

Silent screen stars like Theda Bara, right, helped glamorize Maybelline mascara. By the 1930s, the paraffin to Vaseline to mascara concoction was available at five-and-dime stores for 10 cents a cake.

Inspired by his sister’s example, he began selling the mixture by mail-order catalog, calling it “Lash-Brow-Ine” (an apparent concession to the mascara’s Vaseline content). Women loved it.

When it became clear that Lash-Brow-Ine had potential, Williams, doing business in Chicago as Maybell Laboratories, on April 24, 1917, trademarked the name as a “preparation for stimulating the growth of eyebrows and eyelashes.”

With sales exceeding $100,000 by 1920, Williams renamed the mascara Maybelline in honor of his sister, who worked with him in his Chicago office — and married Chet Hewes in 1926.

An unlikely petroleum product for women’s eyes.

Whatever its petroleum product beginnings, Hollywood helped expand the Williams family cosmetics empire. The 1920s silent screen had brought new definitions to glamour. Theda Bara – an anagram for “Arab Death” – and Pola Negri, each with daring eye makeup, smoldered in packed theaters across the country.

Maybelline trumpeted its mail-order mascara in movie and confession magazines as well as Sunday newspaper supplements. Sales continued to climb. By the 1930s, Maybelline mascara was available at the local five-and-dime store for 10 cents a cake.

Both Vaseline, now part of Unilever, and Maybelline, a subsidiary of L’Oréal, continue with highly successful products, distantly removed from northwestern Pennsylvania’s antique derricks and oil wells.

Unilever’s Park Avenue public relations agency, M Booth & Associates of New York, has proclaimed: “From Vaseline Petroleum Jelly – the ‘Wonder Jelly’ introduced in 1870, to Vaseline Intensive Care Lotion…Vaseline products have helped deliver healthy, moisturized skin for 135 years.”

Special thanks to Linda Hughes, granddaughter of Mabel and Chet Hewes, who reviewed the American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s paraffin to Vaseline to Mascara article. She asked AOGHS add that Mabel was dedicated to her brothers work –- and helped run the Maybelline company in Chicago.

Crayola Crayons

Paraffin from early U.S. oilfields also proved key the phenomenal success of business partners Edwin Binney and C. Harold Smith, who in 1891 patented an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.”

Binney and Smith mixed carbon black with oilfield paraffin and other waxes to introduce a paper-wrapped black crayon marker for crates and barrels.

By 1903, the Binney & Smith Company of Easton, Pennsylvania, was adding colors for a new product, “Crayola” crayons. Learn more about their petroleum products in Carbon Black & Oilfield Crayons.

Oilfield paraffin also soon found its way into novelty candies like “wax lips.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It (2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/vaseline-maybelline-history. Last Updated: April 17, 2024. Original Published Date: March 1, 2005.

(2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.