by Bruce Wells | Jan 16, 2025 | Petroleum Products

When Phillips Petroleum scientists invented a new plastic in the early 1950s, getting it from lab to market proved difficult. Enter Wham-O.

Research scientists in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1951 discovered how to make a durable, high-density polyethylene, and the marketing executives at their oil and natural gas company named it Marlex. But Phillips Petroleum sales reps searched in vain for buyers of the new plastic until the Wham-O toy company found it ideal for making hoops and flying platters.

Prompted by a post World War II boom in demand for plastics, Phillips Petroleum Company invested $50 million to bring its own miracle product — Marlex — to market in 1954. With a high melting point and tensile strength, the synthetic polymer would stand out from the company’s thousands of patents.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jan 14, 2025 | Petroleum Products

“New Perfection” kerosene stoves once competed with coal and wood-burning stoves in rural kitchens.

In the early 1900s, a foundry in Cleveland, Ohio, began manufacturing and selling an alternative to coal or wood-burning cast iron stoves. Thanks to a marketing partnership with Standard Oil Company, millions of rural kitchens would cook with kerosene-burning stoves.

America’s energy future changed after 1859 when a new “coal oil” (kerosene) was refined from petroleum purposefully extracted from wells drilled near Oil Creek, Pennsylvania.

A Cleveland foundry president in 1901 approached John D. Rockefeller about a new, kerosene-fueled alternative to cast iron home stoves like this one.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jan 7, 2025 | Petroleum Products

As more Americans took to the road, inventor S.F. Bowser added a hose attachment for dispensing gasoline directly into automobile tanks in 1905. His popular Model 102 Chief Sentry with its secure “clamshell” cover followed.

The man wearing overalls and a bowler hat pumps gas at the Diamond Filling Station in 1920 at the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and North Capitol Street near Union Station in Washington, D.C.

The Library of Congress photograph of the scene (with the station’s owner?) includes an S.F. Bowser Pump Company Model 102 Chief Sentry with a hand lever that pumped Penn Oil Company lightning Motor Fuel. A quart of Penn Oil motor oil sells for 20 cents.

Manufactured in 1911, an S.F. Bowser Model 102 Chief Sentry is pumped by the station attendant on North Capitol Street in Washington, D.C., in 1920. Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

“This is so cool. So, when you had to pump your gas, you literally had to hand pump the equipment to get the gas to come out?” asks one vintage photographs website blogger. “I’ve honestly never thought about the literal meaning of a phrase that I say all the time. And I feel like a total whippersnapper by asking the question.”

The small “filling station” sold Penn Oil Company’s Lightning Motor Fuel. Four quart of Penn Oil motor oil sold for 80 cents.

According to the blog Shorpy.com, the photograph and others were taken in the Washington, D.C., area by the National Photo Company, whose archive of thousands of negatives (mostly glass plates) and prints was donated by proprietor Herbert E. French to the Library of Congress in 1947.

The popular Bowser “Chief Sentry” pump included an upper clamshell that closed for security when the filling station was left unattended. Showing its wear and tear, the nine-years-old pump’s topmost globe (prized by collectors) survived only as a bare bulb.

Sylvanus Freelove Bowser of Ft. Wayne, Indiana, in 1885 sold his first accurate pump that could reliably measure and dispense kerosene – a product much in demand.

S.F. Bowser added a hose attachment for dispensing gasoline directly into automobile tanks in 1905. His popular Model 102 “Chief Sentry” with its secure “clamshell” cover followed.

Later, as America’s enthusiasm for “horseless carriages” soared, so did demand for gasoline. Bowser refocused his business on gasoline pumps to serve increasing numbers of customers driving automobiles. Bowser’s Self-Measuring Gasoline Storage Pumps soon became known as “filling stations.” Also see Cantankerous Combustion – 1st U.S. Auto Show.

Penn Oil Company was the exclusive American distributer of Lightning Motor Fuel, a British product that reportedly consisting of “50 percent gasoline and 50 per cent of chemicals, the nature of which is secret.”

Lightning Motor Fuel was promoted as offering up to 35 percent more mileage thanks to its secret ingredient, which was likely alcohol. Some writers of the day believed alcohol would eventually replace gasoline refined from petroleum.

“The advantage of alcohol over petrol for this purpose lies principally in the fact that whereas the world’s supplies of petroleum, and therefore of petrol, are being gradually exhausted, the supply of Power Alcohol is practically inexhaustible,” proclaims one 1925 trade journal, Romance of the Fungus World.

The journal added that alcohol’s fuel potential was “only limited by the earth’s capacity of producing plant growths whose products are amenable to the fermentative processes which yield alcohol.”

Today, ethanol is a common additive, but neither Bowser Pump Company, Penn Oil Company, nor Lightning Motor Fuel survived. The last vestige of Bowser Pump Company disappeared from Ft. Wayne in 1969. Learn more in First Gas Pump and Service Station.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title – “Diamond Filling Station.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/diamond-filling-station. Last Updated: May 10, 2025. Original Published Date: July 9, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 16, 2024 | Petroleum Products

Petroleum paraffin soon found its way into candles, crayons, chewing gum…and a peculiar wax candy.

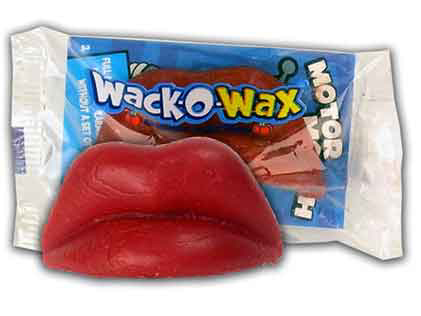

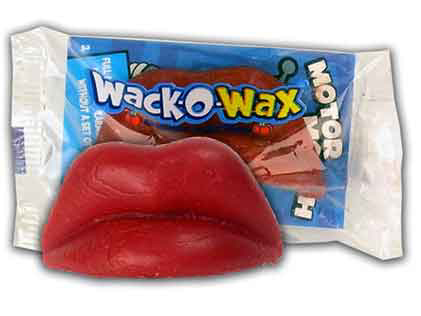

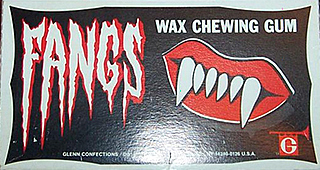

When Ralphie Parker and his 4th-grade classmates dejectedly handed over their Wax Fangs to Mrs. Shields in “A Christmas Story,” a generation might be reminded of what a penny used to buy at the local Woolworth’s store. But there is far more to these paraffin playthings than a penny’s worth of fun.

It’s hard to recall a time when there were no Wax Lips, Wax Moustaches, or Wax Fangs for kids to smuggle into classrooms. Many grownups may remember the peculiar disintegrating flavor of Wax Lips from bygone Halloweens and birthday parties, but few know where these enduring icons of American culture started. The answer can be found by way of the oil patch.

Released on November 18, 1983, “A Christmas Story” featured Ralphie, his 4th-grade classmates – and a popular petroleum product. Photos courtesy MGM Home Entertainment.

Beginning with the August 1859 first commercial U.S. oil well, Pennsylvania oilfields quickly brought an important new source for refining kerosene. “This flood of American petroleum poured in upon us by millions of gallons, and giving light at a fifth of the cost of the cheapest candle,” wrote British chandler James Wilson in 1879.

As kerosene lamps replaced candles for illumination, the much-reduced candle business turned from tallow to versatile paraffin.

A byproduct of kerosene distillation, paraffin found its way from refinery to marketplace in candles, sealing waxes and chewing gums. Ninety percent of all candles by 1900 used paraffin as the new century brought a host of novel uses. Thomas Edison’s popular new phonographs also needed paraffin for their wax cylinders.

Concord Confections, part of Tootsie-Roll Industries, continues to produce Wax Lips and other paraffin candies for new generations of schoolchildren.

Crayons were introduced by the Binney & Smith Company in 1903 and were instantly successful. Alice Binney came up with the name by combining the French word for chalk, craie, with an English adjective meaning oily, oleaginous: Crayola (see Carbon Black and Oilfield Crayons).

In New York City, after collecting unrefined waxy samples from Pennsylvania oil wells, Robert Chesebrough invented a method for turning paraffin into a balm he called “petroleum jelly,” later “Vaseline.” His product also led to a modern cosmetic giant (learn more in The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes).

Paraffin Lips, Fangs, and Horses Teeth

An inspired Buffalo, New York, confectioner soon used fully refined, food-grade paraffin and a sense of humor to find a niche in America’s imagination. When John W. Glenn introduced children to paraffin “penny chewing gum novelties,” his business boomed. By 1923, his J.W. Glenn Company employed 100 people, including 18 traveling sales representatives.

Glenn Confections became the wax candy division of Franklin Gurley’s nearby W.&F. Manufacturing Company. There, the ancestors of Wax Lips chattered profitably down the production line. Among the most popular of these novelties at the time were Wax Horse Teeth (said to taste like wintergreen).

By 1939, Gurley was producing a popular series of holiday candles for the Socony-Vacuum Oil Company using paraffin from a nearby refinery at Olean, New York — once home to the world’s largest crude oil storage site. A field of metal tanks, some holding 20,000 gallons of paraffin, stood next to Gurley’s W.&F. Manufacturing Company in Buffalo.

Glenn Confections, the candy division of W. & F. Manufacturing Company, produced Fun Gum Sugar Lips, Wax Fangs, and Nik-L-Nips.

Decorative and scented paraffin candles soon became the company’s principal products, accounting for 98 percent of W.&F. Manufacturing sales. Gurley’s “Tavern Candle” Santas, reindeer, elves and other colorful Christmas favorites today are prized by collectors on eBay, as are his elaborately molded Halloween candles.

Glenn Confections, the W.&F. wax candy division, has continued to manufacture the popular Fun Gum Sugar Lips and Wax Fangs, with small, wax bottles — Nik-L-Nips — available from the Old Time Candy Company.

In Emlenton, Pennsylvania, a few miles south of Oil City, the Emlenton Refining Company (and later the Quaker State Oil Refining Company) provided the fully refined, food-grade paraffin for the bizarre but beloved treats. Retired Quaker State employee Barney Lewis remembers selling Emlenton paraffin to W.&F. Manufacturing.

During a 2005 interview, Lewis noted, “It was always fun going to the plant…they were very secret about how they did stuff, but you always got a sample to bring home,” adding, “Wax Lips, Nik-L-Nips…the little Coke bottle-shaped wax, filled with colored syrup.”

Concord Confections, a small part of Tootsie-Roll Industries, continues to produce Wax Lips and other paraffin candies for new generations of schoolchildren. The modern petroleum industry produces an astonishing range of products for consumers. But among the many products that find their history in the oilfield, few are as unique and peculiar as Wax Lips.

In December 2007, “A Christmas Story” was ranked the number one Christmas film of all time by AOL. Set in 1940, the movie has been shown in an annual marathon since 1997.

Among the waxy petroleum products featured is a polymer “major award” — the plastic leg-lamp with the black nylon stocking.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Sweet!: The Delicious Story of Candy (2009); How Sweet It Is (and Was): The History of Candy (2003). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oleaginous History of Wax Lips.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/an-oleaginous-history-of-wax-lips. Last Updated: December 15, 2024. Original Published Date: December 1, 2006.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 12, 2024 | Petroleum Products

Camphene and popular but risky burning fluid are replaced by a brighter, less volatile lamp fuel.

In the early 19th century, lamp designs burned many different fuels, including rapeseed oil, lard, and whale oil rendered from whale blubber (and the more expensive spermaceti from the heads of sperm whales), but most Americans could only afford light emitted by animal-fat, tallow candles.

By 1850, the U.S. Patent Office recorded almost 250 different patents for all manner of lamps, wicks, burners, and fuels to meet growing consumer demand for illumination. At the time, most Americans lived in almost complete darkness when the sun went down. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 3, 2024 | Petroleum Products

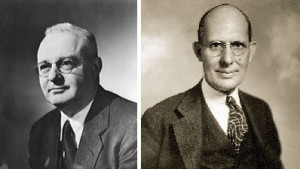

G.M. scientists discover the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead gasoline.

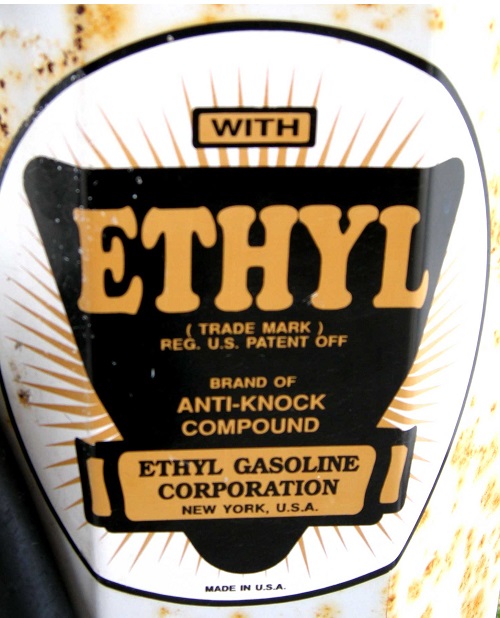

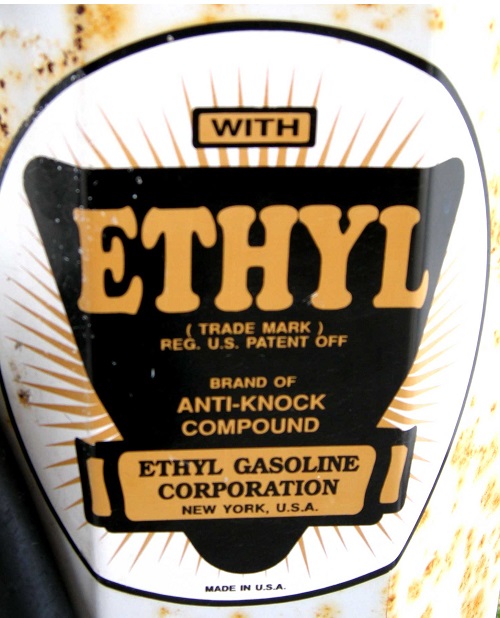

General Motors scientists in 1921 discovered the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead as an additive to gasoline. By 1923, many American motorists would be driving into service stations and saying, “Fill ‘er up with Ethyl.”

Early internal combustion engines often suffered from a severe “knocking,” the out-of-sequence detonation of the gasoline-air mixture in a cylinder. The constant shock added to exhaust valve wear and frequently damaged engines.

Automobiles powered with gasoline had been the least popular models at the November 1900 first U.S. auto Show in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

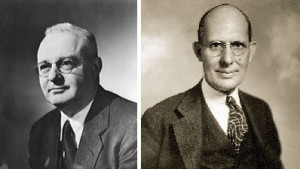

General Motors chemists Thomas Midgely Jr. and Charles F. Kettering tested many gasoline additives, including arsenic.

On December 9, 1921, after five years of lab work to find an additive to eliminate pre-ignition “knock” problems of gasoline, General Motors researchers Thomas Midgely Jr. and Charles Kettering discovered the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead.

Early experiments at GM examined the properties of knock suppressors such as bromine, iodine and tin — comparing these to new additives such as arsenic, sulfur, silicon and lead.

The world’s first anti-knock gasoline containing a tetra-ethyl lead compound went on sale at the Refiners Oil Company service station in Dayton, Ohio. A bolt on “Ethylizer” can be seem running vertically alongside the visible reservoir. Photo courtesy Kettering/GMI Alumni Foundation.

When the two chemists synthesized tetraethyl lead and tried it in their one-cylinder laboratory engine, the knocking abruptly disappeared. Fuel economy also improved. “Ethyl” vastly improved gasoline performance.

“Ethylizers” debut in Dayton

Although being diluted to a ratio of one part per thousand, the lead additive yielded gasoline without the loud, power-robbing knock. With other automotive scientists watching, the first car tank filled with leaded gas took place on February 2, 1923, at the Refiners Oil Company service station in Dayton, Ohio.

In the beginning, GM provided Refiners Oil Company and other service stations special equipment, simple bolt on adapters called “Ethylizers” to meter the proper proportion of the new additive.

“By the middle of this summer you will be able to purchase at approximately 30,000 filling stations in various parts of the country, a fluid that will double the efficiency of your automobile, eliminate the troublesome motor knock, and give you 100 percent greater mileage,” Popular Science Monthly reported in 1924.

By the late 1970s, public health concerns resulted in the phase-out of tetraethyl lead in gasoline, except for aviation fuel.

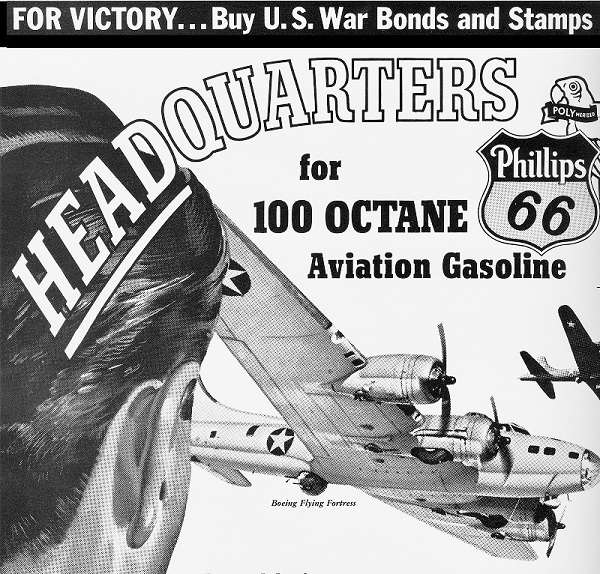

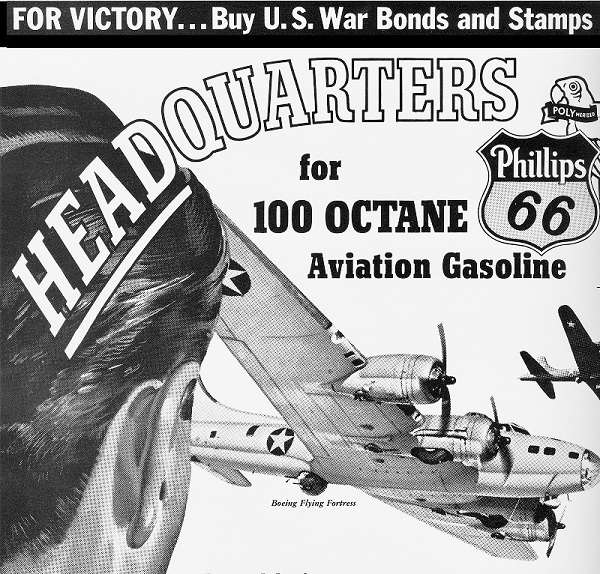

Anti-knock gasoline containing a tetraethyl lead compound also proved vital for aviation engines during World War II, even as danger from the lead content increasingly became apparent.

Powering Victory in World War II

Aviation fuel technology was still in its infancy in the 1930s. The properties of tetraethyl lead proved vital to the Allies during World War II. Advances in aviation fuel increased power and efficiency, resulting in the production of 100-octane aviation gasoline shortly before the war.

Phillips Petroleum – later ConocoPhillips – was involved early in aviation fuel research and had already provided high gravity gasoline for some of the first mail-carrying airplanes after World War I.

Phillips Petroleum produced tetraethyl leaded aviation fuels from high-quality oil found in Osage County, Oklahoma, oilfields.

Phillips Petroleum produced aviation fuels before it produced automotive fuels. The company’s gasoline came from the high-quality oil produced from Oklahoma’s Seminole oilfields and the 1917 Osage County oil boom.

Although the additive’s danger to public health was underestimated for decades, tetraethyl lead has remained an ingredient of 100 octane “avgas” for piston-engine aircraft.

Tetraethyl lead’s Deadly Side

Leaded gasoline was extremely dangerous from the beginning, according Deborah Blum, a Pulitzer-Prize winning science writer. “GM and Standard Oil had formed a joint company to manufacture leaded gasoline, the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation,” she noted in a January 2013 article. Research focused solely on improving the formula, not on the danger of the lead additive.

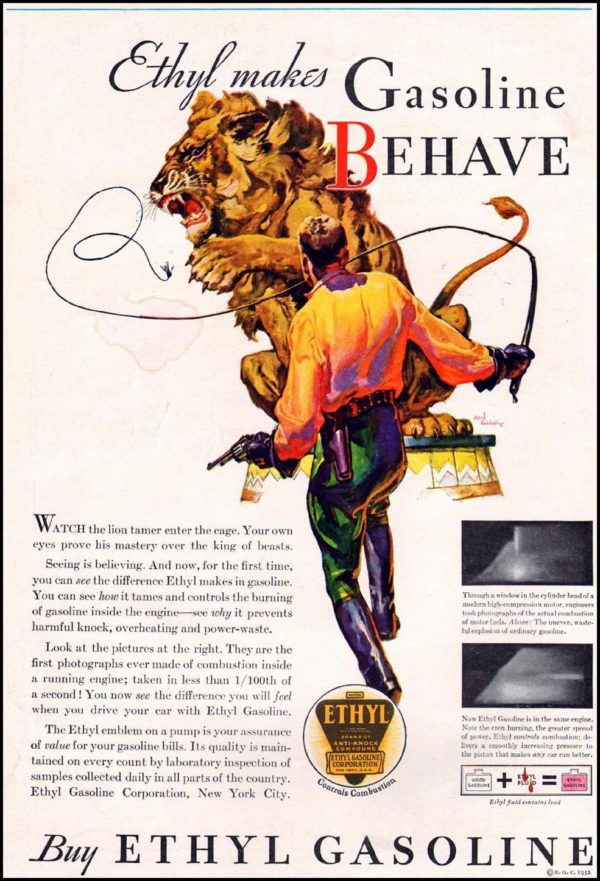

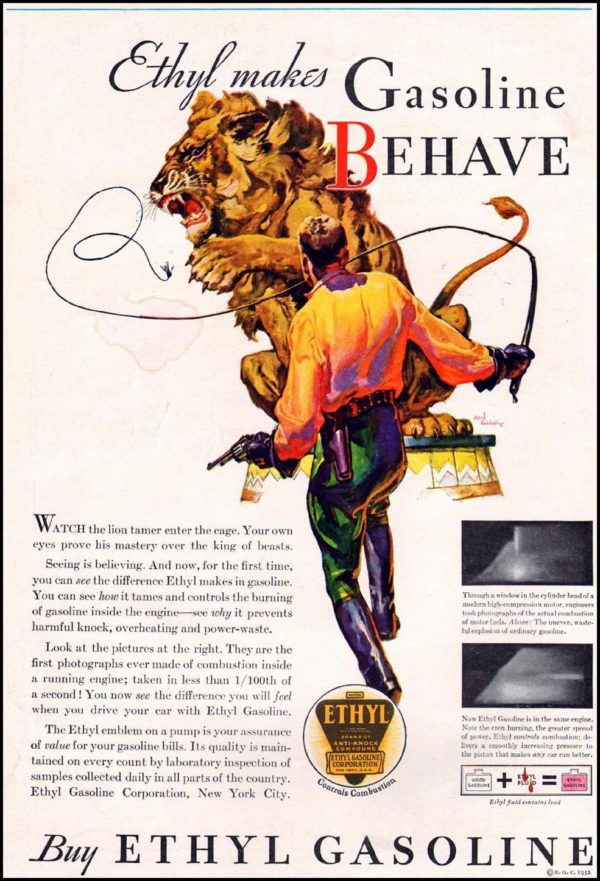

A 1932 magazine advertisement promoted the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation fuel additive as a way to improve high-compression engine performance.

“The companies disliked and frankly avoided the lead issue,” Blum wrote in “Looney Gas and Lead Poisoning: A Short, Sad History” at Wire.com. “They’d deliberately left the word out of their new company name to avoid its negative image.”

In 1924, dozens were sickened and five employees of the Standard Oil Refinery in Bayway, New Jersey, died after they handled the new gasoline additive.

By May 1925, the U.S. Surgeon General called a national tetraethyl lead conference, Blum reported, and an investigative task force was formed. Researchers concluded there was ”no reason to prohibit the sale of leaded gasoline” as long as workers were well protected during the manufacturing process.

So great was the additive’s potential to improve engine performance, the author notes, by 1926 the federal government approved continued production and sale of leaded gasoline. “It was some fifty years later – in 1986 – that the United States formally banned lead as a gasoline additive,” Blum added.

By the early 1950s, American geochemist Clair Patterson discovered the toxicity of tetraethyl lead; phase-out of its use in gasoline began in 1976 and was completed by 1986. In 1996, EPA Administrator Carol Browner declared, “The elimination of lead from gasoline is one of the great environmental achievements of all time.”

Learn more about high-octane aviation fuel in Flight of the Woolaroc.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: An Illustrated Guide to Gas Pumps (2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website, expand historical research, and extend public outreach. For annual sponsorship information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All right reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Ethyl Anti-Knock Gas.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/tetraethyl-lead-gasoline. Last Updated: December 3, 2024. Original Published Date: December 7, 2014.