by Bruce Wells | May 17, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

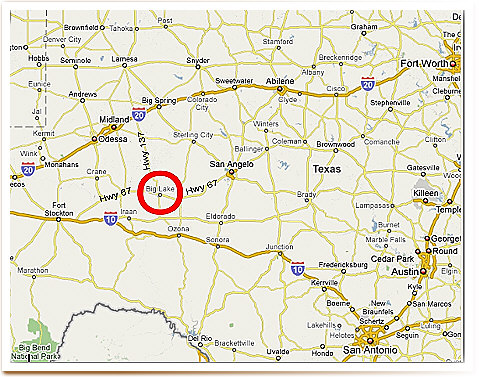

West Texas discoveries in the 1920s revealed a petroleum expanse 250 miles wide and 300 miles long.

A West Texas oil well blessed by nuns revealed the true size of the petroleum-rich Permian Basin in 1923. A small university in Austin owned the arid land, which had been deemed mostly worthless by experts.

Successful exploration of the Permian Basin, once known as a “petroleum graveyard,” began in February 1920 with a discovery by William H. Abrams in Mitchell County in West Texas. When completed after “shooting” the well with nitroglycerin in July, production averaged 20 barrels of oil a day.

In 1958, the University of Texas moved the Santa Rita No. 1 well’s walking beam and other equipment to the Austin campus. The student newspaper described the well, “as one that made the difference between pine-shack classrooms and modern buildings.” Photo from 2007 by Bruce Wells.

The W.H. Abrams No. 1 oilfield discovery well of the Permian Basin would lead to the area’s first commercial oil pipeline in the Permian Basin, according to a Texas Historical Commission historic marker placed near the well in 1996 (reported missing in 2020).

Meanwhile, even with its limited production, the Abrams well began attracting oil exploration to the barren region.

West Texas Oil

It would be another Permian Basin discovery well that launched a stampede of wildcatters to explore the full 300-mile extent of the basin from West Texas into southeastern New Mexico.

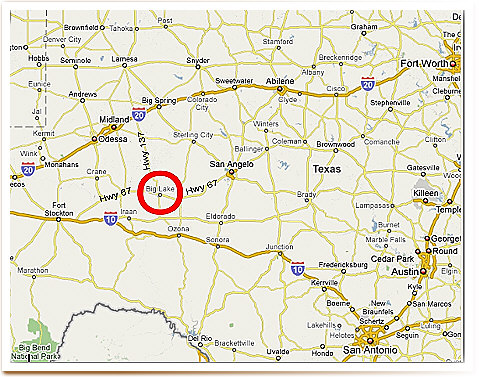

Geologists remained unconvinced the Permian Basin contained commercial amounts of petroleum until the Santa Rita No. 1 well tapped a vast oilfield. The well, drilled by Texon Oil and Land Company near Big Lake, Texas, struck oil on May 28, 1923. The discovery came on land leased from the University of Texas.

It had not been easy for Texon Oil and Land Company. The well required 21 months of cable-tool drilling that averaged less than five feet per day to reach a total depth of 3,055 feet. Once completed, the well produced for the next 70 years.

Because state legislators had given the land and mineral rights to the University of Texas when it opened in 1883, the oilfield’s royalties would endow the University of Texas with $4 million.

Discovery of the Big Lake oil field in 1923 led to many boom towns, including Midland, which some called “Little Dallas.”

The Texas Board of Regents moved Santa Rita’s drilling equipment to the campus in 1958, “In order that it may stand as a symbol of a great era in the history of the university.” After the dedication, the student newspaper of the day described the well “as one that made the difference between pine-shack classrooms and modern buildings.”

Santa Rita No. 1

The historic well’s oil discovery began in 1919 when attorney and oil speculator Rupert Ricker applied to lease rights on more than 430,000 acres of arid land designated by the state for the financing of the University of Texas. As time ran out to pay a filing fee of about $43,000, Ricker failed to raise money from Fort Worth investors.

“Nobody seemed to have any interest in the deal so with the deadline looming he sold the entire scheme to El Pasoans Frank T. Pickrell and Haymon Krupp for the sum of $2,500,” noted a 2017 article in the Permian Basin Petroleum Association Magazine.

The two men had served in the same Army company during World War I. Their Santa Rita No. 1 well near Big Lake started “making hole” shortly before midnight on August 17, 1921 — on the last day before the 18-month drilling permit expired.

A 2007 University of Texas exhibit featured original Santa Rita cable-tool drilling equipment at San Jacinto Boulevard and 19th Street on the Austin campus. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Pickrell hired an experienced Pennsylvania driller, Carl Cromwell, to drill Texon Oil and Land’s test well. Cromwell had been born in 1889 not far from the first commercial U.S. oil well in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Nuns and Roses

At the time, West Texas drilling crews, when available, “consisted mostly of cowboy roustabouts who were distinguished for high absenteeism and steady turnover,” notes one historian. The well often needed to be shut down because of a lack of cash to pay salaries or buy supplies.

Several months after the start of drilling, an increasingly concerned Pickrell climbed the derrick. At the top, he threw handfuls of rose petals that a group of Catholic women investors from New York had given him.

Pickrell christened his wildcat well for the church’s Patroness of Impossible Causes — Santa Rita. On May 25, 1923, early signs of oil and natural gas appeared. Three days later, Santa Rita No. 1 roared in as a West Texas gusher.

People as far away as Fort Worth traveled to see the well. Much-needed casing and other well equipment arrived a month later to bring the wild well under control, and the first commercial well in the Permian Basin went into production.

The Big Lake field — at 4.5 square miles — revealed that vast oil reserves in West Texas came from both shallow and deep formations. Exploration spread into other areas of the Permian Basin, still one of the largest oil-producing regions in the United States.

In the fall of 1923, Pickrell found an important investor, Michael L. Benedum, the highly successful independent oilman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Benedum and another Pittsburgh wildcatter, Joseph Trees, purchased Texon properties and formed the Big Lake Oil Company in 1924.

Big Lake Oilfield

The new company’s president, Levi Smith, would be instrumental in creating Big Lake — the first oil company town in the Permian Basin. Santa Rita No. 1 well, capped in May 1990, would be remembered with a replica erected in Reagan County Park.

The Big Lake oilfield proved to be 4.5 square miles and demonstrated that vast oil reserves in West Texas came from both shallow and deep horizons. Exploration spread into other areas of the Permian Basin, which would become one of the largest oil-producing regions in the United States.

Learn the story of the Permian Basin at the Petroleum Museum in Midland. Not far from the museum, in Odessa, an Ector County historical marker notes “the first Permian Basin dry hole” drilled in 1924.

Pennsylvania independent operators drilled the well to 900 feet and found only “Red Bed” rock, notes the 1965 marker. The 1924 well would be abandoned, but by 1964 Ector County would have 9,600 oil wells.

Hollywood at Big Lake

The 2002 movie “The Rookie” was filmed almost entirely in West Texas. It featured a Big Lake high-school teacher played by Dennis Quaid, who despite being in his mid-30s briefly makes it to the major leagues.

The opening scenes of the 2002 movie “The Rookie” included Catholic nuns christening the wildcat well with rose petals.

As the well is being drilled, Catholic nuns are shown carrying a basket of rose petals to christen it for the patron Saint of the Impossible – Santa Rita.

Learn more about baseball teams fielded by petroleum “company towns” in Oilfields of Dreams.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Santa Rita: The University of Texas Oil Discovery (1958); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin

(1958); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin (2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Santa Rita taps Permian Basin.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/west-texas-petroleum. Last Updated: May 22, 2024. Original Published Date: November 1, 2004.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 2, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

As drillers and speculators rushed to Spindletop Hill, the Texas Company was organized in 1902.

A series of oil and natural gas discoveries at Sour Lake, Texas — near the famous 1901 gusher at Beaumont — helped launch the major oil company Texaco.

Originally known as Sour Lake Springs because of sulfurous spring water popular for its healing properties, a series of oil discoveries brought wealth and new petroleum companies to Hardin County in southeastern Texas.

“A forest of oil well derricks at Sour Lake, Texas,” is from the W.D. Hornaday Collection, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin. Oil discoveries at the resort town northwest of the world-famous Spindletop gusher of 1901 would transform the Texas Company.

As the science of petroleum exploration and production evolved, some geologists predicted oil was trapped at a salt dome at Sour Lake similar to that of Beaumont’s Spindletop Hill formation, which was producing massive amounts of oil.

According to Charles Warner in Texas Oil & Gas Since 1543, in November 1901 an exploratory well found “hot salt water impregnated with sulfur between 800 and 850 feet…and four oil sands about 10 feet thick at a depth of approximately 1,040 feet.”

Warner noted that the Sour Lake Springs field’s discovery well came four months later when a second attempt by the Great Western Company drilled “north of the old hotel building” in the vicinity of earlier shallow wells.

“This well secured gusher production at a depth of approximately 683 feet on March 7, 1902,” Warner reported. “The well penetrated 40 feet of oil sand. The flow of oil was accompanied by a considerable amount of loose sand, and it was necessary to close the well in from time to time and bail out the sand, after which the well would respond with excellent flows.”

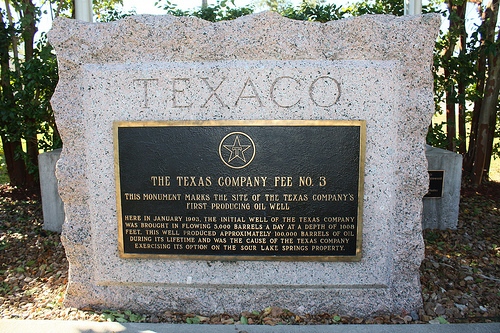

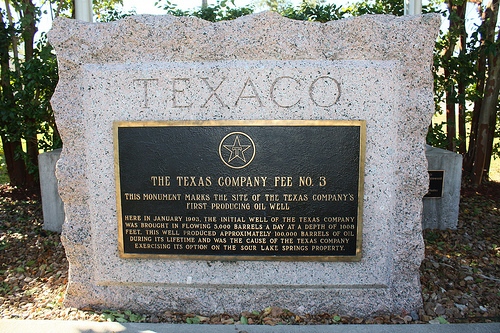

A monument marks the site where in 1903 the Fee No. 3 well flowed at 5,000 barrels of oil a day, launching the Texas Company into becoming Texaco.

As more discoveries followed, Joseph “Buckskin Joe” Cullinan and Arnold Schlaet were among those who rushed to the area from their offices in Beaumont.

The Texas Company

The most significant company that started during the Spindletop oil boom was The Texas Company, according to historian Elton Gish.

“Cullinan worked in the Pennsylvania oil industry and later went to Corsicana, Texas, about 1898 when oil was first discovered in that district where he became the most prosperous operator in the field,” reported Gish in his “History of the Texas Company and Port Arthur Works Refinery.”

Cullinan formed the Petroleum Iron Works, building oil storage tanks in the Beaumont area — where he was introduced to Schlaet. “When the Spindletop boom came in January 1901, Mr. Cullinan decided to visit Beaumont,” Gish noted. Schlaet managed the oil business of two brothers, New York leather merchants.

Named after its New York City telegraph address, the Texaco brand became official in 1959. Postcard of a Texaco service station next to a cafe in Kingman, Arizona.

“Schlaet’s field superintendent, Charles Miller, traveled to Beaumont in 1901 to witness the Spindletop activity and met with Cullinan, whom he knew from the oil business in Pennsylvania. He liked Cullinan’s plans and asked Schlaet to join them in Beaumont.”

According to Texaco, Cullinan and Schlaet formed the Texas Company on April 7, 1902, by absorbing the Texas Fuel Company and inheriting its office in Beaumont. Texas Fuel had organized just one year earlier to purchase Spindletop oil, develop storage and transportation networks, and sell the oil to northern refineries.

By November 1902, the new Texas Company was establishing a new refinery in Port Arthur as well as 20 storage tanks, building its first marine vessel, and equipping an oil terminal to serve sugar plantations along the Mississippi River.

Fee No. 3 Discovery

The Texas Company struck oil at Sour Lake Springs in January 1903, “after gambling its future on the site’s drilling rights,” the company explained. “The discovery, during a heavy downpour near Sour Lake’s mineral springs, turned the company into a major oil producer overnight, validating the risk-taking insight of company co-founder J.S. Cullinan and the ability of driller Walter Sharp.”

A Texaco station was among the 2012 indoor exhibits featured at the National Route 66 Museum in Elk City, Oklahoma. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Their 1903 Hardin County discovery at Sour Lake Springs — the Fee No. 3 well — flowed at 5,000 barrels a day, securing the Texas Company’s success in petroleum exploration, production, transportation and refining. Sharp founded the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company in 1908 with Howard Hughes Sr.

High oil production levels from the Sour Lake field and other successful wells in the Humble oilfield (1905), secured the company’s financial base, according to L. W. Kemp and Cherie Voris in Handbook of Texas Online.

“In 1905 the Texas Company linked these two fields by pipelines to Port Arthur, ninety miles away, and built its first refinery there. That same year the company acquired an asphalt refinery at nearby Port Neches,” the authors noted.

“In 1908 the company completed the ambitious venture of a pipeline from the Glenn Pool, in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), to its Southeast Texas refineries,” added Kemp and Voris. “As early as 1905 the Texas Company had established marketing facilities not only throughout the United States, but also in Belgium, Luxembourg, and Panama.”

The Texas Company registered “Texaco” as a trademark in 1909.

The telegraph address for the company’s New York office is “Texaco” — a name soon applied to its products. The company registered its first trademark, the original red star with a green capital letter “T” superimposed on it in 1909. The letter remained an essential component of the logo for decades.

The Texas Corporation in August 1926 incorporated in Delaware (from Texas) and by an exchange of shares acquired outstanding stock of The Texas Company (Texas), which was dissolved the next year.

The new corporation became the parent company of numerous “Texas Company” — Texaco — entities and other subsidiaries, according to Jim Hinds of Columbus, Indiana (see Histories of Indian Refining, Havoline, and Texaco). By 1928, Texaco operated more than 4,000 gasoline stations in 48 states. It already was a major oil company when it officially renamed itself Texaco in 1959.

1987 Bankruptcy

Texaco lost a 1985 court battle following its purchase of Getty Oil Company. In February 1987 a Texas court upheld the decision against Texaco for having initiated an illegal takeover of Getty Oil after Pennzoil had made a bid for the company. Texaco filed for bankruptcy in April 1987.

The companies settled their historic $10.3 billion legal battle for $3 billion when Pennzoil agreed to drop its demand for interest. The Los Angeles Times reported the compromise was vital for Texaco emerging from bankruptcy, a haven sought to stop Pennzoil from enforcing the largest court judgment ever awarded at the time.

On October 9, 2001, Chevron and Texaco agreed to a merger that created ChevronTexaco — renamed Chevron in 2005. Although the Sour Lake Springs oil boom was surpassed by other Texas discoveries, it has remained the birthplace of Texaco.

Learn more about southeastern Texas petroleum history in Spindletop creates Modern Petroleum Industry and Prophet of Spindletop.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Texaco Story, The First Fifty Years 1902 – 1952 by Texas Company (1952). Texaco’s Port Arthur Works, A Legacy of Spindletop and Sour Lake (2003); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Sour Lake produces Texaco.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/sour-lake-produces-texaco. Last Updated: March 1, 2025. Original Published Date: April 5, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 5, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

The Ranger who tamed oil and gas boom towns during the Great Depression. “Crime may expect no quarter.”

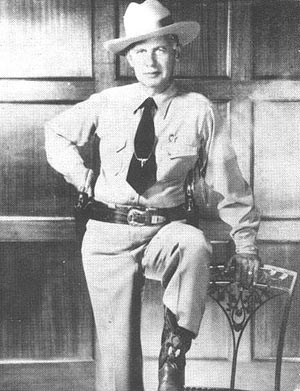

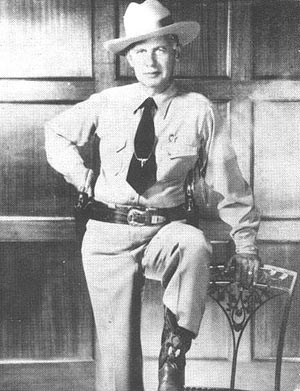

During much of the 1920s, a Texas Ranger became known for strictly enforcing the law in oilfield communities. By 1930, the discovery year of the largest oilfield in the lower 48 states, he was known as “El Lobo Solo” — the lone wolf — the Ranger who brought law and order to East Texas boom towns.

Manuel Trazazas Gonzaullas was born in 1891 in Cádiz, Spain, to a Spanish father and Canadian mother who were naturalized U.S. citizens. At age 15 he witnessed the murder of his only two brothers and the wounding of his parents when bandits raided their home. Fourteen years later, Gonzaullas joined the Texas Rangers.

“Give Texas more Rangers of the caliber of ‘Lone Wolf’ Gonzaullas and the crime wave we are going through will not be of long duration,” reported the Dallas Morning News in 1934.

“He was a soft-spoken man and his trigger finger was slightly bent,” independent producer Watson W. Wise characterized him during a 1985 interview in Tyler, Texas. “He always told me it was geared to that .45 of his.” (more…)

(1958); Chronicles of an Oil Boom: Unlocking the Permian Basin

(2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.