by Bruce Wells | Aug 23, 2024 | Petroleum Pioneers

The U.S. petroleum industry began in 1859 to meet demand for “Coal Oil” — the popular lamp fuel kerosene.

American oil history began in a valley along a creek in remote northwestern Pennsylvania. Today’s exploration and production industry was born on August 27, 1859, near Titusville when a well specifically drilled for oil found it.

Although crude oil had been found and bottled for medicine as early as 1814 in Ohio and in Kentucky in 1818, these had been drilled seeking brine. Drillers often used an ancient technology, the “spring pole” Sometimes the salt wells produced small amounts of oil, an unwanted byproduct.

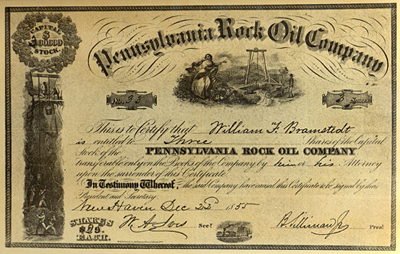

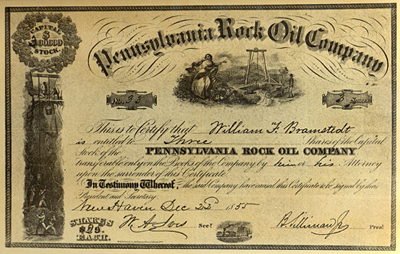

Considered America’s first petroleum exploration company – the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of New York – incorporated in 1854. It reorganized as Seneca Oil Company of New Haven Connecticut in 1858.

The advent of cable-tool drilling introduced the wooden derrick into the changing American landscape. The technology applied same basic idea of chiseling a hole deeper into the earth.

Using steam power, a variety of heavy bits, and improved mechanical engineering skills, cable-tool drillers became more efficient. (Learn more Making Hole – Drilling Technology.) (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Aug 22, 2024 | Petroleum Art

Postal Service commemorates U.S. petroleum history centennial with 120 million stamps.

A centennial oil stamp commemorating the birth of the U.S. oil and natural gas industry was issued on August 27, 1959, by Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield, who proclaimed: “The American people have great reason to be indebted to this industry. It has supplied most of the power that has made the American standard of living possible.”

As the sesquicentennial of the first U.S. well drilled to produce oil approached in 2009, a special “Oil 150” committee sought U.S. Postal Service approval for a commemorative stamp. The committee and historians in more than 30 petroleum-producing states petitioned for a stamp similar to one issued for the industry’s 1959 centennial of the first commercial U.S. oil well. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jun 11, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

When Edwin L. Drake drilled the first U.S. oil well in 1859 along a creek at Titusville, Pennsylvania, he transformed the landscape of the Allegheny River valley — and America’s energy future. The former railroad conductor’s discovery launched a new industry as investors and drillers rushed to cash in on the new resource for making kerosene for lamps.

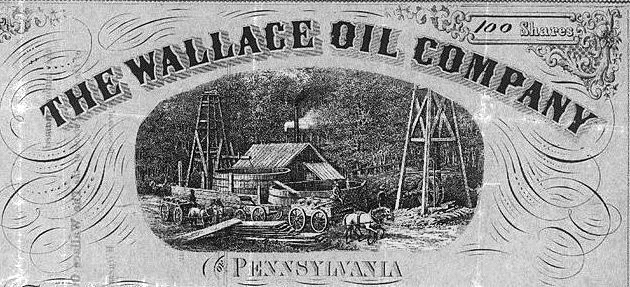

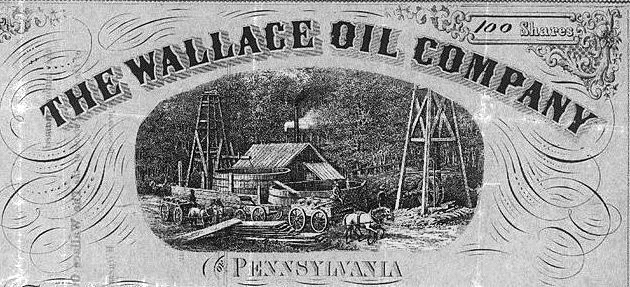

Wallace Oil Company would be among the earliest U.S. petroleum companies, and the venture’s fate would presage the riskiness of America’s new exploration and production industry.

Grocery store owner John Wallace formed the Wallace Oil Company in 1865 to drill for “black gold.” Detail from Wallace Oil Company stock certificate.

The ensuing scramble fueled the nation’s first petroleum drilling boom. Newspapers reported discoveries on farms clustered in Northwestern Pennsylvania’s “oil region.”

Newly incorporated oil companies rushed to construct wooden derricks with steam-powered cable tools for “making hole.”

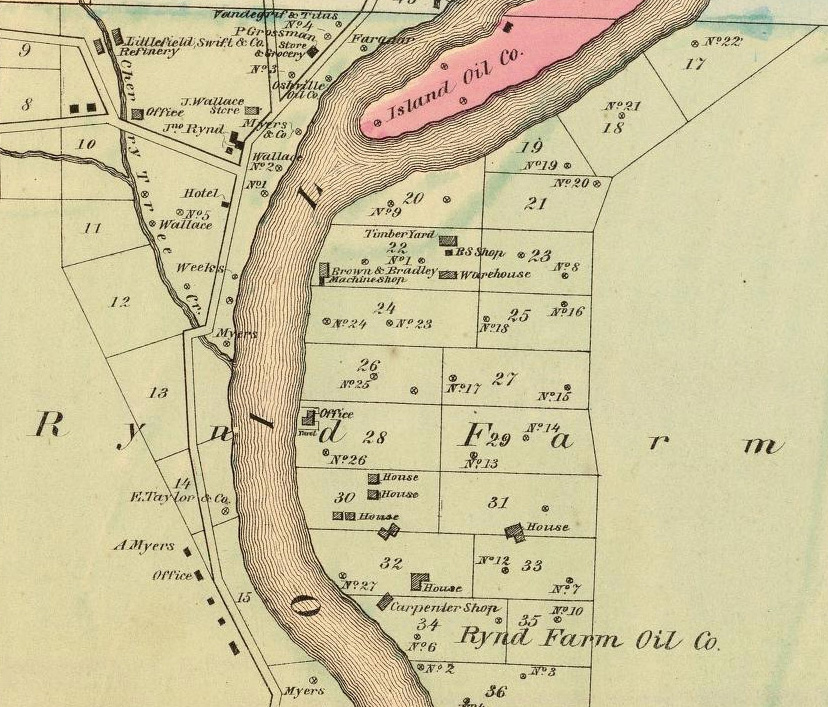

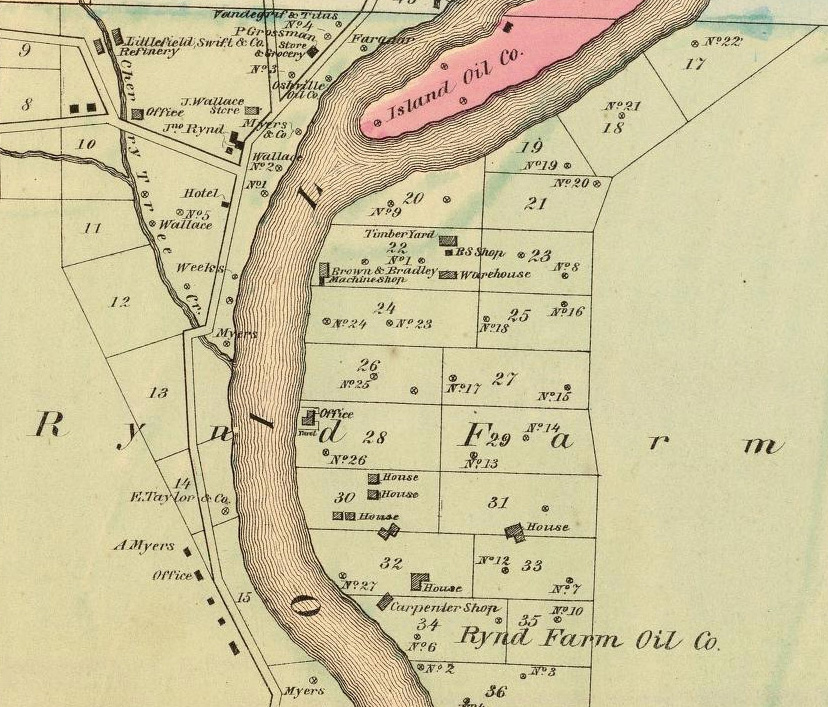

Drillers came to John Rynd’s farm at the junction of Oil Creek and Cherry Tree Run, the Blood farm to the north, and the widow McClintock farm to the south.

Pennsylvania Oil Fever

Operating a grocery store on the Rynd farm in 1859, Irish immigrant John Wallace witnessed the excitement firsthand. When the first of many wells found oil on the farm in 1861, derricks already crowded nearby hillsides. Four years later, the 24-year-old entrepreneur caught oil fever and incorporated Wallace Oil Company in 1865 with an office at 319 Walnut Street in Philadelphia.

After witnessing the oil region’s drilling boom from his Rynd farm grocery store, John Wallace caught oil fever. “Oil Region of Pennsylvania,1865” map courtesy David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, F.W. Beers & Co.

With the science of petroleum geology in its infancy, “creekology” and oil seeps often were the only tools for finding promising locations to drill. Some exploration companies turned to dowsing (hazel or peach tree rods preferred) to find oil.

Wallace’s company sold stock certificates and acquired a 3/32 royalty interest in a 200-acre tract on the neighboring McClintock farm (previously owned by investors Curtiss, Haldeman, and Fawcett).

Although records offer no evidence of Wallace Oil Company actually drilling and completing a well, Wallace’s lease trading speculations, financed by his 3/32 royalty income, and energetic sales of stock, made the company money.

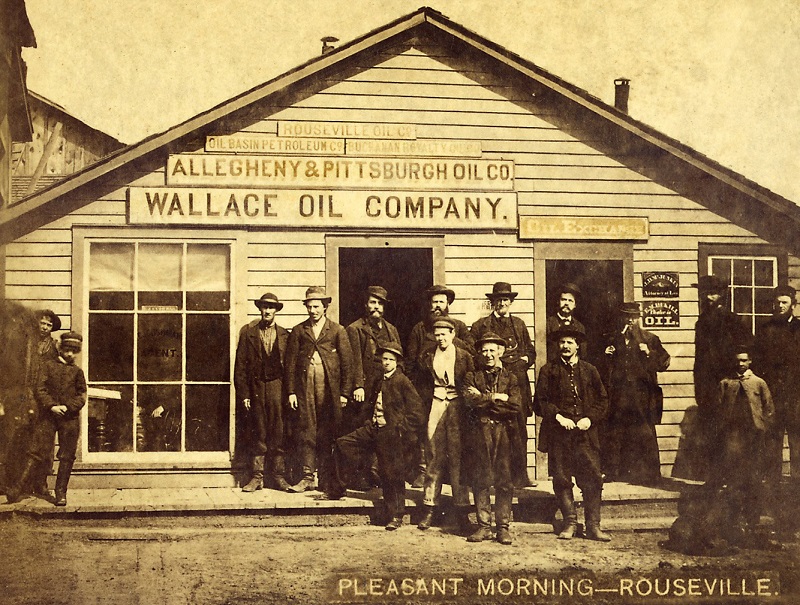

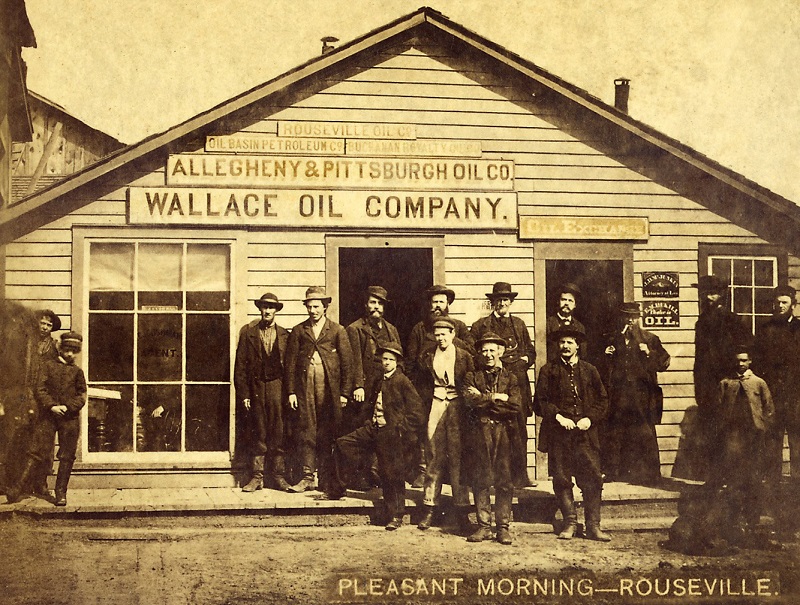

A circa 1875 building at Rouseville in the Pennsylvania oil region hosted an attorney, lease agents, a small oil exchange, and petroleum companies like Wallace Oil Company. Detail from stereograph “Pleasant morning – Rouseville,” courtesy Library of Congress.

Purchasers of Wallace’s stock stood to gain from both royalties and appreciation. The financial horizon looked promising. In 1865, a 42-gallon barrel of oil sold for $6.59 a barrel (nearly $100 in 2013 dollars).

Boom and Bust

As the gamble to find oil spread, Pithole Creek and other oilfield discoveries inspired more drilling — and speculation at oil exchanges in Titusville, Oil City, and elsewhere.

Those seeking petroleum riches in 1864 included John Wilkes Booth, whose Dramatic Oil Company drilled on a 3.5-acre lease on the Fuller farm.

By the end of 1869, Wallace Oil Company ‘s McClintock farm leases still produced an average of 200 barrels of oil daily from 32 wells. It took three more years before Wallace Oil Company paid its first and only dividend to investors, who received one cent per share in 1874. But by then, one industry publication noted, “oil had left the territory.”

The company dutifully paid the state an annual “Tax on Stock,” and in 1871 paid its first “Tax on Income.”

A circa 1875 Library of Congress stereograph of a small building includes signs for the “Wallace Oil Company,” the “Allegheny & Pittsburgh Oil Co.,” the “Oil Basin Petroleum Co.,” the “Buchanan Royalty Oil Co.,” and the “Rouseville Oil Co.”

Rouseville in 1861 had been the scene of a deadly oil well fire, one the earliest fatal conflagrations of the U.S. oil and natural gas industry.

By the early 1890s, Wallace Oil Company’s expanded oil-region holdings were reduced to the original 3/32 royalty from its McClintock property, which no longer produced commercial quantities of oil. Overproduction had drained profitability from the countryside.

In August 1895, American Investor reported Wallace Oil Company had lost its wells and property and could not even muster resources to pay legal fees associated with formal dissolution of the company. The grim assessment concluded, “The company is in a hopeless condition. The stock has no market value.”

Visit the Drake Well Museum and Park in Titusville.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Wallace Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/wallace-oil-company. Last Updated: June 11, 2024. Original Published Date: June 17, 2021.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 22, 2023 | Petroleum Technology

Exploring circa 1914 oilfield production technology found hidden in Pennsylvania woods.

The search for new technologies for pumping oil from wells — pump jacks — began soon after America’s first commercial discovery in 1859 near Titusville, Pennsylvania. For that well, driller Edwin L. Drake used a common water-well hand pump from a nearby kitchen. (more…)