by Bruce Wells | Dec 3, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

New Mexico wildcatter discovers high-grade uranium after decades of drilling dry holes.

Stella Dysart spent almost 30 years unsuccessfully searching for oil in New Mexico. In 1955, a radioactive uranium sample from one of her “dusters” made her a very wealthy woman.

In the end, it was the uranium — not petroleum — that made Dysart her fortune. The sometimes desperate promoter of oil drilling ventures in New Mexico for more than 30 years, she once served time for fraud. But in 1955, Mrs. Dysart learned she owned the world’s richest deposit of high-grade uranium ore.

LIFE magazine featured Stella Dysart in 1955 after she made a fortune from finding uranium but failed in her oil ventures.

Born in 1878 in Slater, Missouri, Dysart moved to New Mexico, where she got into the petroleum and real estate business in 1923. She ultimately acquired a reported 150,000 acres in the remote Ambrosia Lake area 100 miles west of Albuquerque, on the southern edge of the oil-rich San Juan Basin.

Dysart established the New Mexico Oil Properties Association and the Dysart Oil Company. The ventures and other investment schemes would leave her broke, according to John Masters and Paul Grescoe in their 2002 book, Secret Riches: Adventures of an Unreformed Oilman.

The authors describe Dysart as a woman who drilled dry holes, peddled worthless parcels of land to thousands of dirt-poor investors, and went to jail for one of her crooked deals.

Dysart subdivided her properties and subdivided again — selling one-eighth acre leases and oil royalties as small as one-six thousandth to investors. She drilled nothing but dry holes for years. Then it got worse.

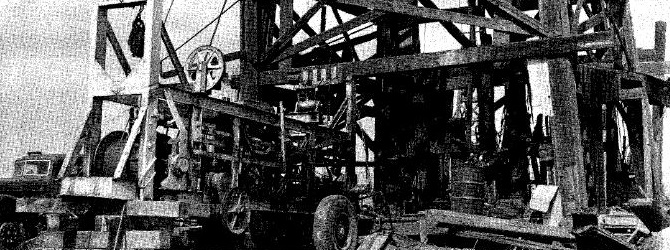

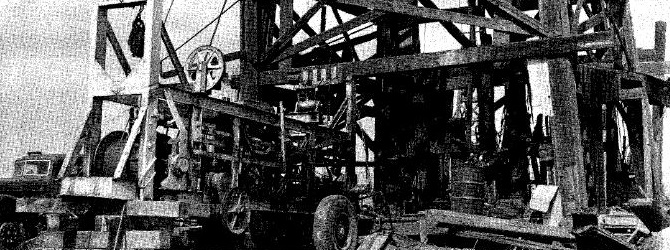

Before finding uranium, Stella Dysart served 15 months for the unauthorized selling of New Mexico oil leases. In 1941, she promoted her Dysart No. 1 Federal well, above, which was never completed.

A 1937 Workmen’s Compensation Act judgment against Dysart’s New Mexico Oil Properties Association bankrupted the company, compelling sale of its equipment, “sold as it now lies on the ground near Ambrosia Lake.”

Two years later, it got worse again. Dysart and five Dysart Oil Company co-defendants were charged with 60 counts of conspiracy, grand theft, and violation of the Corporate Securities Act in 1939. All were convicted, and all did time. Dysart served 15 months in the county jail before being released on probation in March 1941.

Uranium Riches

By 1952, 74-year-old Dysart was $25,000 in debt when she met uranium prospector Louis Lothman, a young Texan just two years out of college with a geology degree.

When Lothman examined cuttings from a Dysart dry hole in McKinley County in 1955, he got impressive Geiger counter readings. The drilling of several more test wells confirmed the results. Dysart owned the world’s richest deposit of high-grade uranium ore.

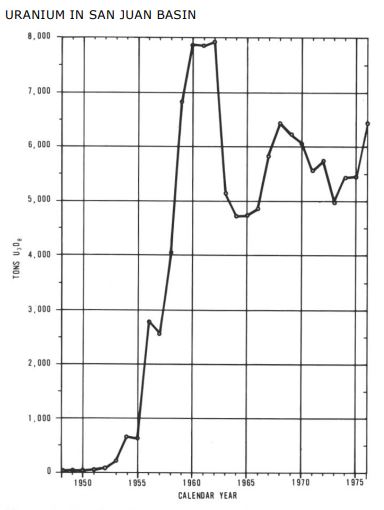

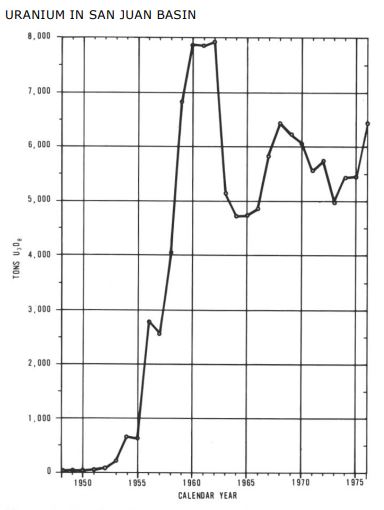

Uranium production in the San Juan Basin, 1948-1975 courtesy New Mexico Geological Survey.

The uranium discovery launched an intensive exploration effort that led to the development of multi-million-ton deposits in the Ambrosia Lake area, according to William L. Chenoweth of the U.S. Energy Research and Development Administration.

“The San Juan Basin of northwest New Mexico has been the source of more uranium production than any other area in the United States,” he noted in a New Mexico Geological Survey 1977 report, “Uranium in the San Juan Basin.”

Dysart was 78 years old when the December 10, 1955, LIFE magazine featured her picture, captioned: “Wealthy landowner, Mrs. Stella Dysart, stands before abandoned oil rig which she set up on her property in a long vain search for oil. Now uranium is being mined there and Mrs. Dysart, swathed in mink, gets a plump royalty.”

Praised for her success, and memories of fraudulent petroleum deals long forgotten, Dysart died in 1966 in Albuquerque at age 88. As Secret Riches author John Masters explained, “there must be a little more to her story, but as someone said of Truth — ‘it lies hidden in a crooked well.’”

More New Mexico petroleum history can be found in Farmington, including the exhibit “From Dinosaurs to Drill Bits” at the Farmington Museum. Learn about the giant Hobbs oilfield of the late 1920s in New Mexico Oil Discovery.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Stella Dysart of Ambrosia Lake: Courage, Fortitude and Uranium in New Mexico (1959); Secret Riches: Adventures of an Unreformed Oilman (2004). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1959); Secret Riches: Adventures of an Unreformed Oilman (2004). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: Legend of “Mrs. Dysart’s Uranium Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/uranium. Last Updated: December 3, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 17, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

November 18, 1847 – Manufactured Gas illuminates U.S. Capitol –

Lamps fueled by “coal gas” began replacing whale oil lamps in the U.S. Capitol. Manufactured gas distilled beneath the Capitol flowed through newly installed pipes into light fixtures, including chandeliers in both House chambers. James Crutchett had invented the lighting system and convinced Congress to appropriate $17,500 to fund his plan, which included a lantern atop the dome.

A mast with a gas lantern was erected on the U.S. Capitol dome in 1847. The rotunda interior used 1,083 gas jets by 1865. Incandescent lighting began in 1885. Image courtesy Architect of the Capitol.

Onlookers witnessed “one of the most splendid and beautiful spectacles we ever beheld,” according to David Rotenstein in History Sidebar. Crutchett built a gas plant in the Capitol’s northwest quadrant, placing lighting fixtures throughout the building.

Although the dome’s 80-foot mast and lantern would be removed within a year, a citywide manufactured gas system followed — similar to ones established in Philadelphia and Baltimore (see Illuminating Gaslight).

November 19, 1861 – America exports Oil for First Time

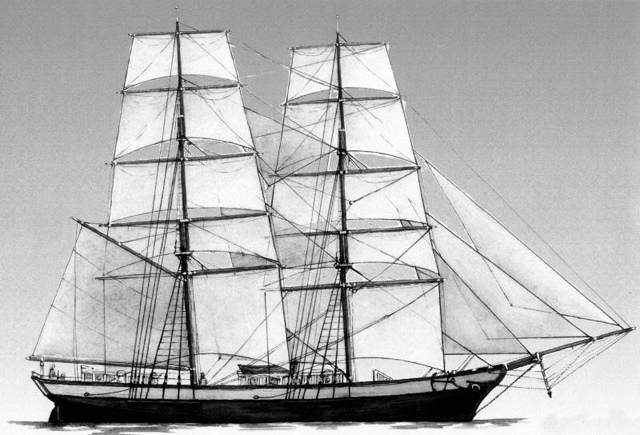

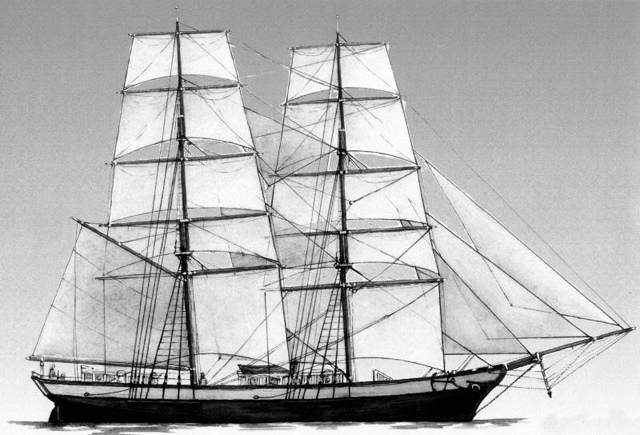

America exported petroleum for the first time when the merchant brig Elizabeth Watts departed the Port of Philadelphia for Great Britain. The Union vessel arrived in London 45 days later carrying a cargo of 901 barrels of Pennsylvania oil and 428 barrels of refined kerosene.

Launched in 1847 by the shipbuilding firm of J. & C.C. Morton of Thomaston, Maine, the Elizabeth Watts was about 96 feet long with a draft of 11 feet.

The shippers were the successful Philadelphia import-export firm of Peter Wright & Sons, which since its founding in 1818 had prospered transporting glass, porcelain, and queensware china. The company hired the brig Elizabeth Watts to ship the petroleum to three British companies. On January 9, 1862, the brig sailed down the Thames River to arrive at London, where it took 12 days to unload the 1,329 barrels of oil and kerosene.

Learn more in America exports Oil.

November 19, 1927 – Phillips Petroleum introduces “Phillips 66” Gasoline

After a decade as an exploration and production company, Phillips Petroleum entered the business of refining and retail gasoline distribution. The Bartlesville, Oklahoma, company introduced a new line of gasoline — “Phillips 66” — at its first service station, which opened in Wichita, Kansas.

Originally promoted as a dependable “winter gasoline,” by 1930 “Phillips 66” gasoline was marketed in 12 states.

The gasoline was named “Phillips 66” because it had propelled company officials down U.S. Highway 66 at 66 mph on the way to a meeting at their Bartlesville headquarters. The roadway became part of Phillips Petroleum marketing plans for the new product, which boasted “controlled volatility,” the result of a higher-gravity mix of naphtha and gasoline.

By 1930, Phillips 66 gasoline was sold at 6,750 outlets in 12 states. Because the composition made Phillips 66 gas easier to start in cold weather, ads enticed motorists to try the “New Winter Gasoline.”

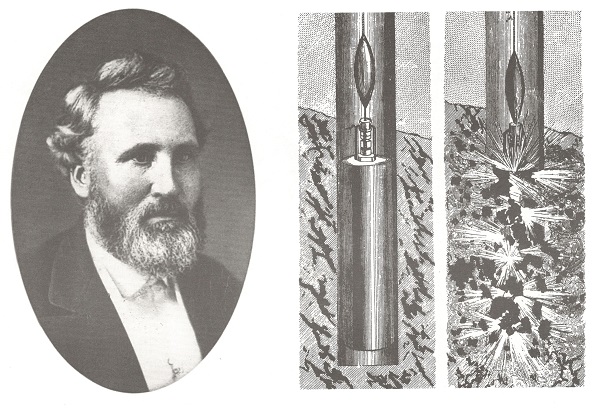

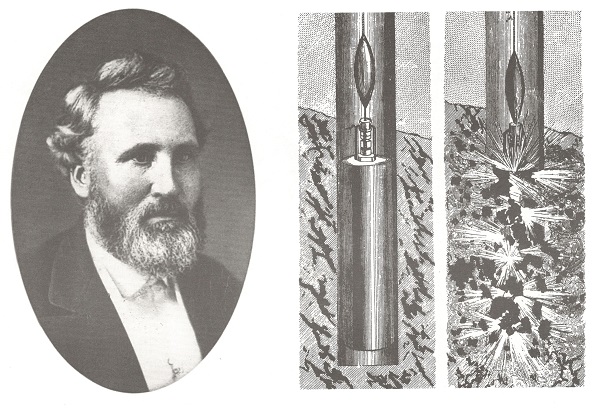

November 20, 1866 – Improved Well Torpedo patented

Col. Edward A.L. Roberts of New York City patented improvements to his Roberts Torpedo, an oilfield technology for increasing production by fracturing oil-bearing formations. “Our attention has been called to a series of experiments that have been made in the wells of various localities by Col. Roberts, with his newly patented torpedo,” noted the Titusville Morning Herald newspaper in 1865. “The results have in many cases been astonishing.”

Portrait of Col. Edward Roberts, the Union Civil War veteran who patented well “torpedo” technologies that vastly improved oil production.

The Civil War Union Army veteran would receive many patents for his “Exploding Torpedoes in Artesian Wells” method to increase petroleum production (see Shooters – A “Fracking” History).

November 20, 1930 – Oil Booms bring Hilton Hotels to Texas

After buying his first hotel in the booming oil town of Cisco, Texas, Conrad Hilton opened a high-rise in El Paso. While visiting Cisco in 1919, Hilton had witnessed roughnecks from the Ranger oilfield waiting for rooms. Hilton’s first hotel, the Mobley, offered 40 rooms for eight-hour periods to coincide with workers’ shifts. Thanks to booming oilfields, Hilton was firmly established in Texas. His El Paso Hilton (now the Plaza Hotel) was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

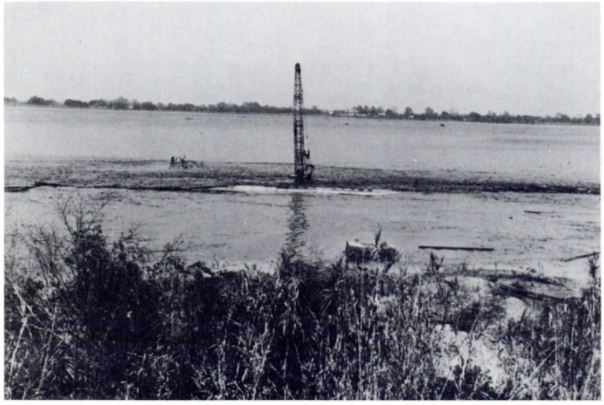

November 20, 1980 – Well taps Salt Mine, drains Louisiana Lake

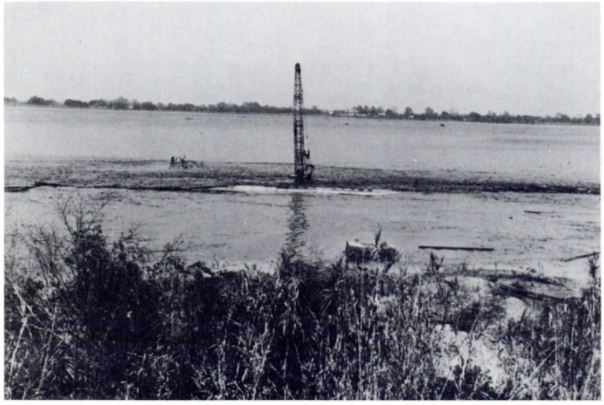

Minutes after its drilling crew evacuated, a Texaco drilling platform overturned and disappeared into a whirlpool that drained Lake Peigneur, Louisiana, over the next three hours. The crew had accidentally penetrated a salt dome containing the mining operations of Diamond Crystal Salt Company.

All 50 miners working as deep as 1,500 feet below the surface escaped with no serious injuries as a maelstrom swallowed the $5 million Texaco platform — and 11 barges holding drilling supplies.

Photo from a 1981 government study of the “Jefferson Island Mine Inundation,” Texaco’s accidental drilling into a salt mine one year earlier. Photo courtesy Federal Mine Safety and Health Investigation Report.

“Texaco, who had ordered the oil probe, was aware of the salt mine’s presence and had planned accordingly; but somewhere a miscalculation had been made, which placed the drill site directly above one of the salt mine’s 80-foot-high, 50-foot-wide upper shafts,” noted a 2005 article about the Lake Peigneur vortex.

According to a 1981 government report, “Jefferson Island Mine Inundation,“ evidence for identifying the exact cause was washed away, but Texaco and Wilson Drilling paid $32 million to Diamond Crystal Salt Company and another $12.8 million to a nearby botanical garden. Changed from freshwater to saltwater with a depth reaching 200 feet, Lake Peigneur became the deepest lake in Louisiana.

November 21, 1925 – Magnolia Petroleum incorporates

Formerly an unincorporated joint-stock association with roots dating to an 1889 refinery in Corsicana, Texas, Magnolia Petroleum Company incorporated. The original association had sold many grades of refined petroleum products through more than 500 service stations in Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas.

Magnolia Petroleum operated gas stations throughout the Southeast.

Within a month of the new company’s founding, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil of New York (Socony) purchased most Magnolia Petroleum assets and operated it as a subsidiary. Magnolia merged with the Socony Mobile Oil Company in 1959 and adopted the red Pegasus logo at gas stations. Magnolia Petroleum assets were part of the 1999 merger that created ExxonMobil.

Learn more in Mobil’s High-Flying Trademark.

November 21, 1980 – Millions watch “Dallas” Episode

The cliffhanger episode “Who shot J.R.?” on the prime-time soap opera “Dallas” was watched by 83 million people in the United States and 350 million worldwide. The CBS show debuted in 1978 and revolved around two Texas oil families, one featuring Larry Hagman as J.R. Ewing, “the character fans loved to hate,” according to History.com. Hagman’s portrayal of a “greedy, conniving, womanizing scoundrel” and the business dealings of Ewing Oil Company would stereotype the Texas petroleum industry for seasons.

November 22, 1878 – Tidewater Pipe Company established

Byron Benson organized the Tidewater Pipe Company in Pennsylvania. In 1879 his company would build the first oil pipeline to cross the Alleghenies from Coryville to the Philadelphia Reading Railroad 109 miles away in Williamsport. This technological achievement was considered by many as the first true oil pipeline in America, if not the world.

Despite protests from teamsters, a 109-mile oil pipeline revolutionized oil transportation. Photo courtesy explorepahistory.com.

The difficult work — much of it done in winter using sleds to move pipe sections — bypassed Standard Oil Company’s dominance in transporting petroleum. Tidewater made an arrangement with Reading Railroad to haul the oil in tank cars to Philadelphia and New York. In 1879, about 250 barrels of oil from the Bradford field was pumped across the mountains and into Williamsport.

More than 80 percent of America’s oil soon would come from Pennsylvania oilfields, according to Floyd Hartman Jr. in a 2009 article, “Birth of Coryville’s Tidewater Pipe Line.”

November 22, 1905 – Glenn Pool Field discovered in Indian Territory

Two years before Oklahoma statehood, the Glenn Pool (or Glenpool) oilfield was discovered in the Creek Indian Reservation south of Tulsa. The greatest oilfield in America at the time, it would help make Tulsa the “Oil Capital of the World.” Many independent oil producers, including Harry F. Sinclair and J. Paul Getty, got their start during the Glenn Pool boom.

An oilfield pioneers monument was dedicated in April 2008 at Glenpool, Oklahoma. Photo by Bruce Wells.

With production exceeding 120,000 barrels of oil a day, Glenn Pool exceeded Tulsa County’s earlier Red Fork Gusher. The giant oilfield even exceeded production from Spindletop Hill in Texas four years earlier. The Ida Glenn No. 1 well, drilled to about 1,500 feet deep, led to more prolific wells in the 12-square-mile Glenn Pool.

By the time of statehood in 1907, Tulsa area oilfields made Oklahoma the biggest U.S. oil-producing state. Learn more in Making Tulsa “Oil Capital of the World.”

November 22, 2003 – Smithsonian Museum features Transportation

A permanent exhibit about U.S. transportation history opened at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. “Get your kicks on 40 feet of Route 66,” the Smithsonian exhibit noted on opening day of the $22 million renovation of the museum’s Hall of Transportation.

Opened in 2003 after a $22 million renovation, the Transportation Hall of the National Museum of American History exhibits 340 historic objects in 26,000 square feet. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Hundreds of artifacts are displayed in chronological order, allowing visitors “travel back in time and experience transportation as it changed America,” the hall today includes examples of the first models of Oldsmobile, Franklin, and Cadillac. Also preserved is the Duryea brothers’ 1893-1994 model, considered to be the first American car driven by an internal combustion engine.

Learn more in America on the Move.

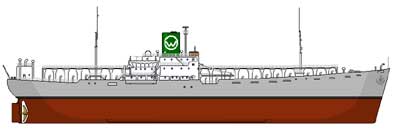

November 23, 1947 – World’s First LPG Ship

The first U.S. seagoing Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) ship went into service as Warren Petroleum Corporation of Tulsa, Oklahoma, sent the Natalie O. Warren from the Houston Ship Channel to Newark, New Jersey. The vessel had an LPG capacity of 38,053 barrels in 68 vertical pressure tanks.

The Natalie O. Warren, a converted freighter, had an LPG capacity of 38,053 barrels in 68 vertical pressure tanks.

The one-of-a-kind ship was the former Cape Diamond dry-cargo freighter before being converted by the Bethlehem Steelyard in Beaumont, Texas. The experimental design led to innovative maritime construction standards for such vessels.

Warren Petroleum became the largest producer and marketer of natural gasoline and propane in the world by the early 1950s, according to an exhibit at the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum. LPG tankers today carry 20 times the capacity of the early vessels.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum (2016); History Of Oil Well Drilling

(2016); History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Be My Guest

(2007); Be My Guest (1957); Magnolia Oil News Magazine

(1957); Magnolia Oil News Magazine (January 1930); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals

(January 1930); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals (1993); Glenn Pool…and a little oil town of yesteryear

(1993); Glenn Pool…and a little oil town of yesteryear (1978); The American Highway: The History and Culture of Roads in the United States

(1978); The American Highway: The History and Culture of Roads in the United States (2000); Natural Gas: Fuel for the 21st Century

(2000); Natural Gas: Fuel for the 21st Century (2015). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2015). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

he American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 25, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

As she researched her family’s distant connection to the U.S. oil patch, Marianne Jans of the Netherlands contacted the American Oil & Gas Historical Society in 2023. She has since continued to hope visitors to the AOGHS Petroleum History Research Forum might add to her limited information about her great-great uncle who worked in Texas oilfields, apparently as a drilling contractor from the 1920s until the early 1930s.

Ralph “Dutch” Weges

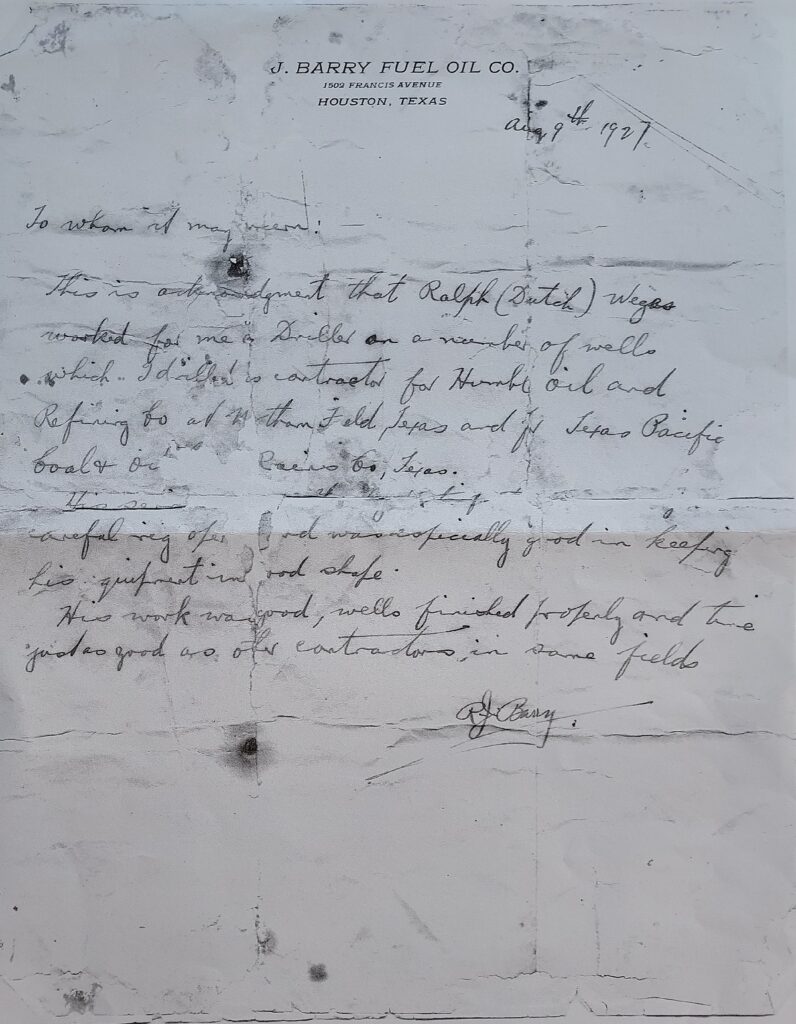

Although details are scarce, Jans seeks news about her great-great uncle Ralph “Dutch” Weges — who in 1962 reportedly returned to the Netherlands by ship. His petroleum-related career included serving on merchant vessels. Regarding his work in Texas, she has a 1927 letter of recommendation with some clues.

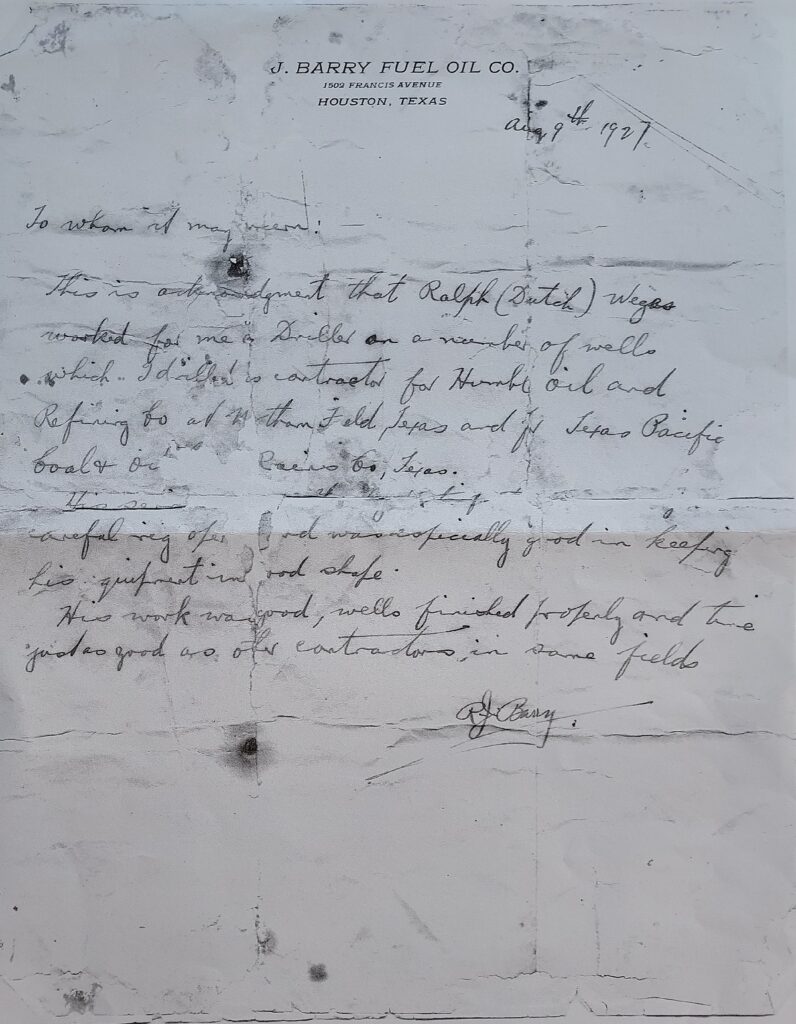

Marianne Jans’ scan of the August 1927 Barry Fuel Oil Company’s letter of recommendation for her great-great uncle, Ralph Weges.

“In papers he left behind, he also had a recommendation from his employer in 1927,” according to Jans. “J. Barry Fuel Oil Co. is not in your list of historic companies, so I am sending this document.” she added.

Transcription of the great-great uncle’s letter, dated August 9, 1927:

J. Barry Fuel Oil Co.

1501 Francis Avenue

Houston, Texas

Aug 9th 1927

To whom it may concern:

This is acknowledgement that Ralph (Dutch) Weges

worked for me [&] Drilled on a number of wells

which I drilled as contractor for Humble Oil and

Refining [unreadable] Northern Field, Texas and [for] Texas Pacific

Coal & Oil [unreadable] Co, Texas.

His [unreadable] careful rig [unreadable] and was specifically good in keeping

his equipment in good shape.

His work was good, wells finished properly and time

just as good as other contractors in same fields.

RJ Barry

J. Barry Fuel Oil

Not finding more information about the J. Barry Fuel Oil Company, Jans learned more about the two well-documented companies J. Barry worked with as a drilling contractor.

Humble Oil and Refining Company (now ExxonMobil) was founded in 1917. The company, which would discover many oilfields, in 1933 signed an historic lease with the King Ranch. The other company referenced in the letter was the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

SS La Campine

In addition, Ralph Weges had other connections with the U.S. petroleum industry, according to Jan’s research. Her great-great uncle traveled overseas aboard the SS La Campine in September 1916.

Launched in 1889, La Campine was an early transatlantic oil tanker owned by the American Petroleum Company of Rotterdam and later by an Esso subsidiary in Belgium (it was sunk by a German submarine during World War I).

“What surprised me, was that Ralph Weges was anyway on board two ships that transported cargo for Esso, now Exxon Mobile,” Jans noted. “So he already worked for a petroleum/oil company on these ships. First as a 2nd cook and later petty officer. Two other vessels, the Anacortes and the SS Vigo, I must research further.”

As her investigation into family history continues from the Netherlands, Marianne Jans seeks information about her great-great uncle’s overseas career, the J. Barry Fuel Oil Company, and his role in Texas oilfields,

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Driller from Netherlands.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/driller-from-netherlands. Last Updated: October 20, 2025. Original Published Date: October 24, 2023.

(1959); Secret Riches: Adventures of an Unreformed Oilman (2004). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.