by Bruce Wells | Jan 10, 2026 | Petroleum History Almanac

The North Texas church proclaimed richest in America.

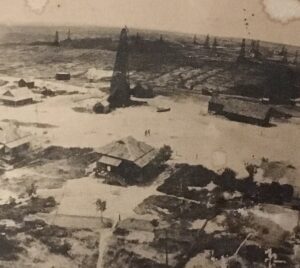

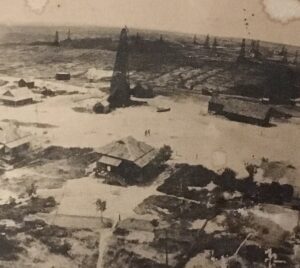

In the fall of 1917 near Ranger, Texas, the cotton-farming town of Merriman was inhabited by “ranchers, farmers, and businessmen struggling to survive an economic slump brought on by severe drought and boll weevil-ravaged cotton fields.”

Everything changed in Eastland County when a wildcat well drilled by Texas & Pacific Coal Company struck oil at Ranger, four miles from Merriman. The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 well produced 1,600 barrels of oil a day.

The 1917 headline-making McCleskey No. 1 cable-tool well — called “Roaring Ranger” — brought an oil boom to Eastland County, Texas, about 100 miles west of Dallas.

The rush to acquire leases that followed the oilfield discovery became legendary among drilling booms, even for Texas, home to the legendary 1901 gusher at Spindletop.

WWI Wave of Oil

As drilling continued, the yield of the Ranger oilfield led to peak production reaching more than 14 million barrels in 1919. Production from the “Roaring Ranger” well and its giant North Texas oilfield helped win World War I, with a British War Cabinet member declaring, “The Allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil.”

Texas & Pacific Coal Company had taken a great risk by leasing acreage around Ranger, but the risk paid off when lease values soared. The exploration company added “oil” to its name, becoming the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

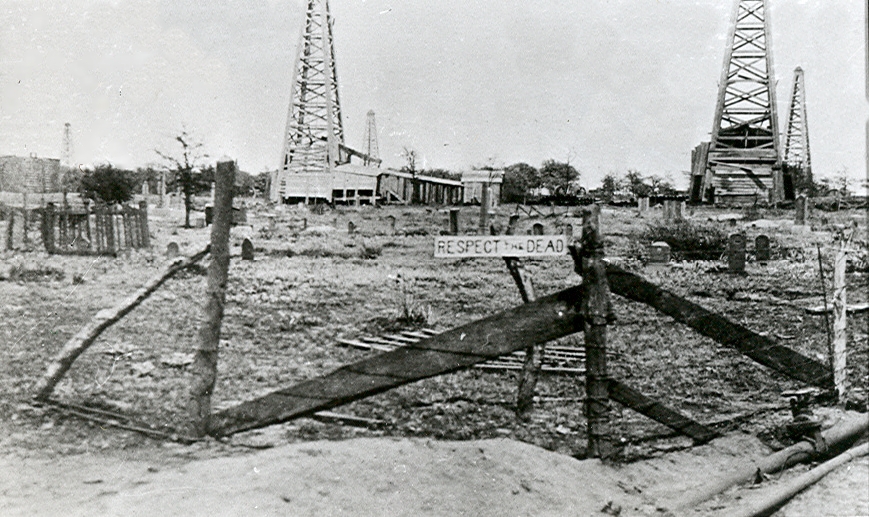

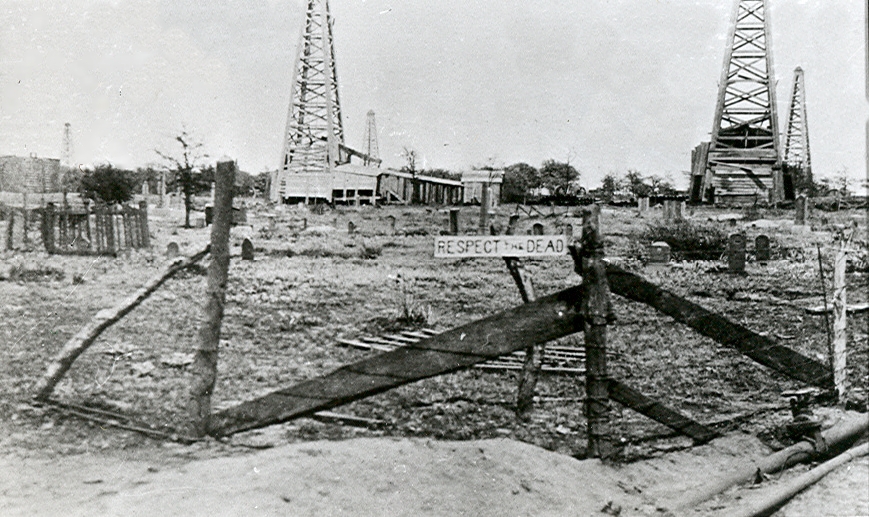

“So as we could not worship God on the former acre of ground, we decided to lease it and honor God with the product,” explained Merriman Baptist Church Deacon J.T. Falls. Photo courtesy Robert Vann, “Lone Star Bonanza, the Ranger Oil Boom of 1917-1923.”

The price of the oil company stock jumped from $30 a share to $1,250 a share as a host of landmen “scanned the landscape to discover any fractions in these holdings. A little school and church, before too small to be seen, now looked like a skyscraper.”

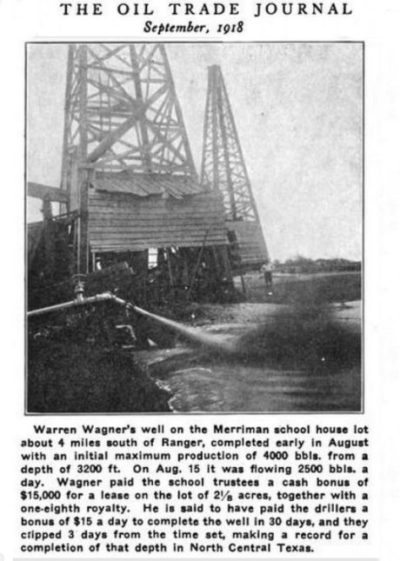

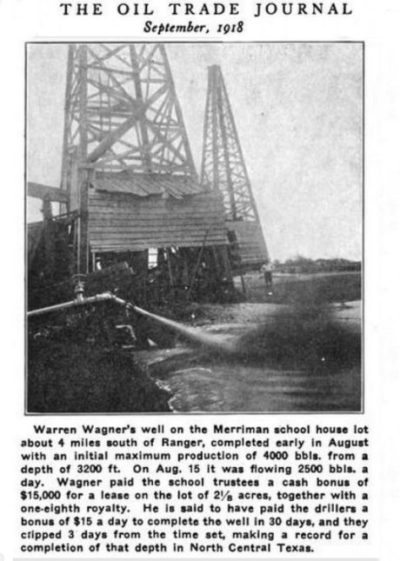

Warren Wagner, driller of the McCleskey discovery well, leased the local school lot and in August 1918 completed a well producing 2,500 barrels of oil a day. Leasing at Merriman Baptist Church proved to be a challenge.

In February, Deacon J.T. Falls complained that drilling new wells “ran us out, as all of the land around our acre was leased, producing wells being brought in so near the house we were compelled to abandon the church because of the gas fumes and noisy machinery.”

Falls added that, “As we could not worship God on the former acre of ground, we decided to lease it and honor God with the product.”

Deacon J.T. Falls (second from left) was not amused when the Associated Press reported in 1919 that his church had refused a million dollars for the lease of the cemetery.

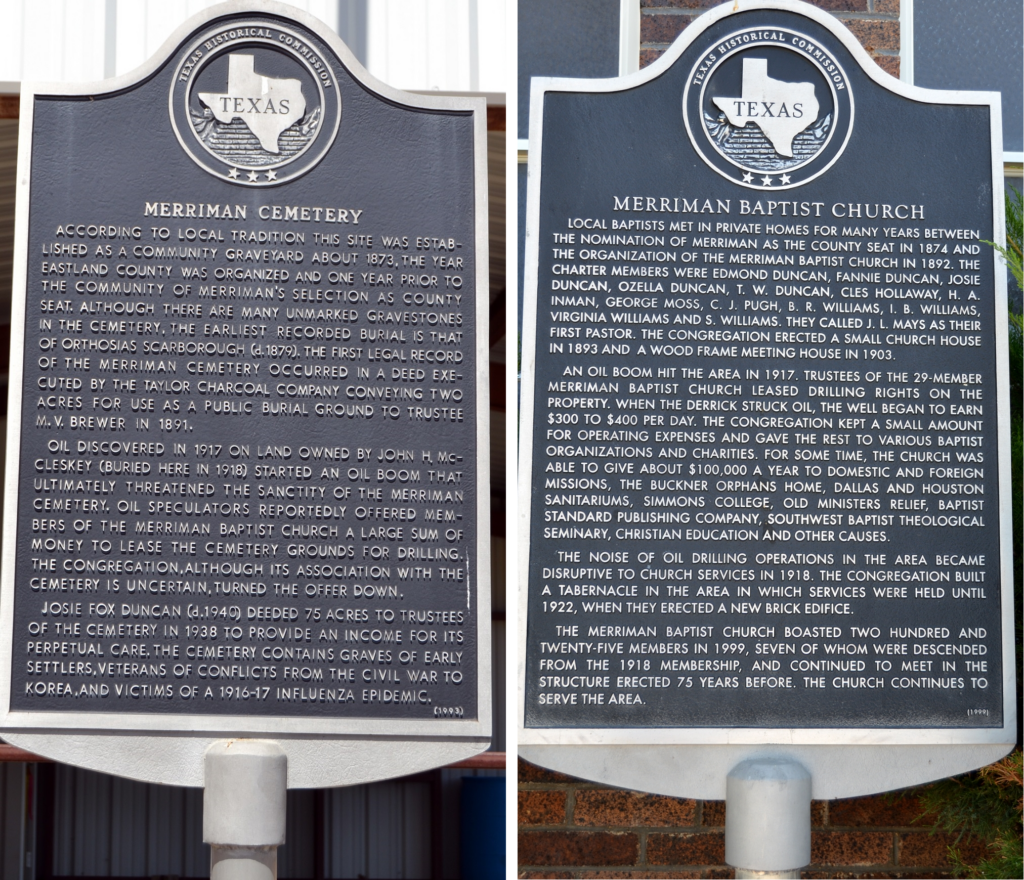

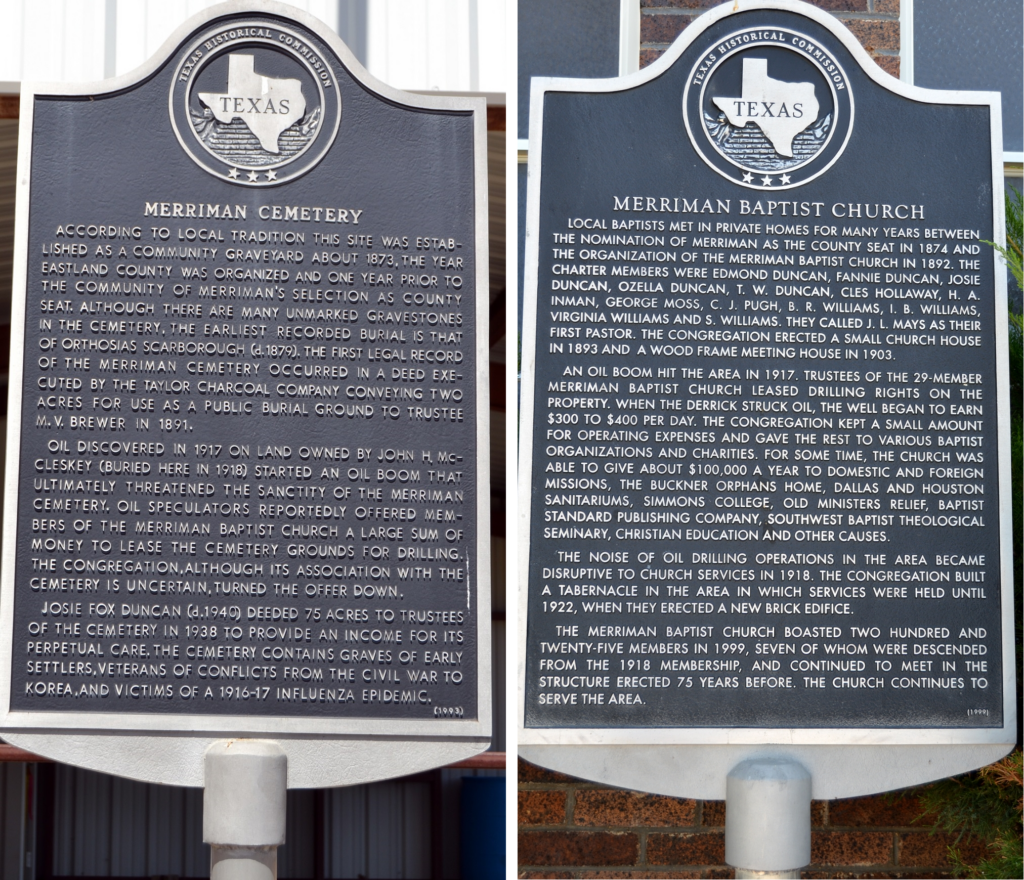

A Texas Historical Commission marker erected in 1999 described when the well on the church’s lease began producing oil, earning the congregation a royalty of between $300 and $400 a day. Merriman Baptist Church “kept a small amount for operating expenses and gave the rest to various Baptist organizations and charities.”

However, drilling in the church graveyard was a different matter. As oil production continued to soar in North Texas, the congregants of Merriman Baptist Church initially resisted one drilling site. As a January 18, 1919, article in the New York Times noted in its headline, “CHURCH MADE RICH BY OIL; Refuses $1,000,000 for Right to Develop Wells in Graveyard.”

Respecting the Dead

At Merriman’s church cemetery, a less seen historical marker erected in 1993 explains the drilling boom’s fierce competition to find property without a well already on it: “Oil speculators reportedly offered members of the Merriman Baptist Church a large sum of money to lease the cemetery grounds for drilling.”

Near Ranger in Eastland County, Texas Historical Commission markers were erected in 1993 (left) and 1999 explaining how members of the Merriman Baptist Church shared their wealth from petroleum royalties. Photos courtesy the Historical Marker Database.

When local newspapers reported the church had refused an offer of $1 million, the Associated Press picked it up, and newspapers from New York to San Francisco ran the story. Literary Digest even featured “the Texas Mammon of Righteousness” with a photograph of “The Congregation That Refuses A Million.”

Deacon J.T. Falls was not amused. “A great many clippings have been sent to us from many secular papers to the effect that we as a church have refused a million dollars for the lease of the cemetery. We do not know how such a statement started,” the deacon opined.

“The cemetery does not belong to the church. It was here long before the church was. We could not lease it if we would, and we would not if we could,” the cleric added.

“If any person’s or company’s heart has become so congealed as to want to drill for oil in this cemetery, they could not — for the dead could not sign a lease, and no living person has any right to do so,” Falls proclaimed.

The church deacon concluded with an ominous admonition to potential drillers, “Those that have friends buried here have the right and the will to protect the graves, and any person attempting to trespass will assume a great risk.”

A 1918 article noted a “Merriman school house” oil well drilled to 3,200 feet in record time for North Central Texas.

Roaring Ranger’s oil production dropped precipitously because of dwindling reservoir pressures brought on by unconstrained drilling. Many exploration and production companies failed (including fraudulent ones like Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company).

In the decades since the McCleskey No. 1 well, advancements in horizontal drilling technology have presented more legal challenges to mineral rights of the interred, according to Zack Callarman of Texas Wesleyan School of Law.

In 2014, Callarman wrote an award-winning analysis of laws concerning drilling to extract oil and natural gas underneath cemeteries. “Seven Thousand Feet Under: Does Drilling Disturb the Dead? Or Does Drilling Underneath the Dead Disturb the Living?” was published in the Real Estate Law Journal.

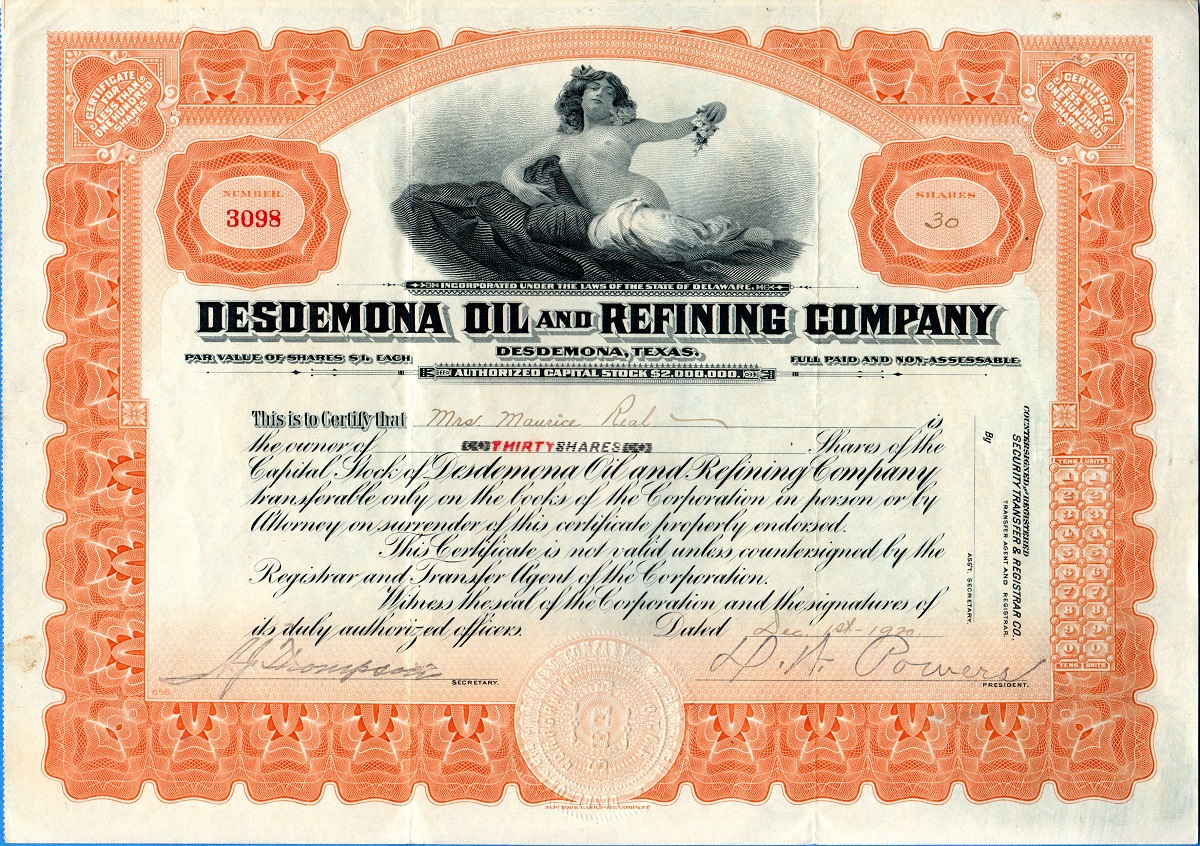

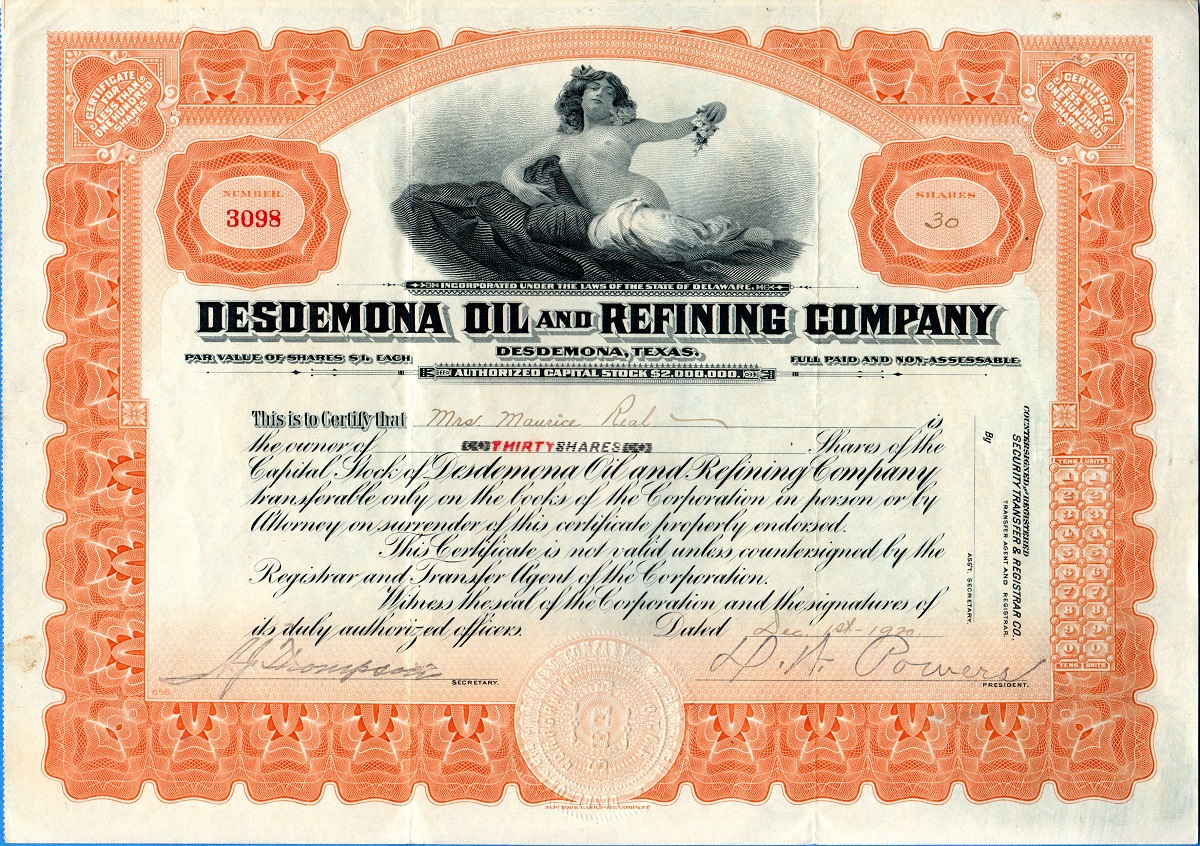

Despite yet another North Texas oilfield discovery at Desdemona, by 1920 the Eastland County drilling boom was over. The faithful still gather at Merriman Baptist Church every Sunday.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2000);Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2000);Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History (2013);Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(2013);Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen (1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: January 11, 2026. Original Published Date: January 18, 2019.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 2, 2026 | Petroleum History Almanac

A simple forum for sharing ideas and research — and preserving history.

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) established this oil history forum page to help share research. For oilfield-related family heirlooms, the society also maintains an Oil & Gas Families page to locate suitable museum collections for preserving these unique histories. Information about old petroleum company stock certificates can be found at the popular forum linked to Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

Our forum below offers a simple way to share personal or academic research, subject ideas, comments, and other details about petroleum history. You can email the society at bawells@aoghs.org if you would like your research question posted. Please use the comment section at the bottom of this page to answer or make suggestions!

Request: January 5, 2026

Sherwood Forest Drilling Photograph

Retired police officer and author Michael Layton of Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, United Kingdom, is working on a sequel to his 2025 local history, Top Secret West Midlands. He seeks suggestions for finding a photo.

“I am obviously at the beginning of my research but have already noticed that Sherwood Forest in Nottingham was home to a secret drilling operation during WW2 involving 42 American drillers. It will not be a huge piece in the book, but I think it highlights a little known and very important piece of WW2 history in Nottinghamshire. Would any AOGHS members or website visitors have access to a photograph of that period which would not be the subject of copyright restrictions?”

I look forward to any suggestions. Kind regards — Michael

Please post your reply in the comments section below or email layton2006@btinternet.com

Request: November 21, 2025

1914 Socal Tanker served in WWII

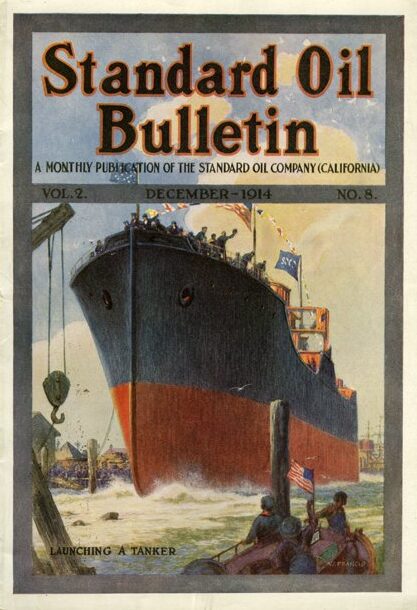

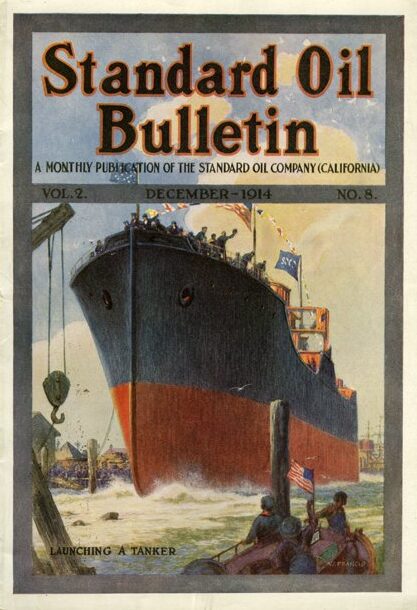

Searching for the SOCAL publication featuring the 1914 launch of the company tanker J.A. Moffett, which served in WWII.

“Hello. I’m trying to find out if American Oil & Gas Historical Society website visitors have any information about the December 1914 Standard Oil Company of California ‘Standard Oil Bulletin.'”

Created with the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911, Standard Oil of California (SOCAL) became Chevron in 1984.

The cover story for that “Standard Oil Bulletin” featured the tanker J.A. Moffett. “My dad was on that tanker in World War II in the Pacific, and I’m trying to find a copy or the J.A. Moffett article. Thank you.”

— Pat

Editor’s Note: Another tanker, the J. A. Moffett Jr., built in 1921, was torpedoed in 1942 in the Florida Keys. Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org

Research Request: November 16, 2025

Hand-cranked Bowser Pump

Scottish researcher seeks details about a salvaged pump manufactured by S.F. Bowser & Company.

“I have an old hand-crank petrol pump that I salvaged from a demolition site. The body can be closed and locked by swinging a curved door round. It’s possible to just make out the word Bowser on a part. It has a light bulb holder up top where a glass globe could be fitted and two other bulb holders to shine downwards. It can be set to serve a pint, a quart, a half gallon or a gallon.

“I’d love to know more about it but can’t find an image anywhere showing the same appliance.”

Douglas Robertson

Please post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email douglasinscotland@gmail.com

Research Update: November 12, 2025

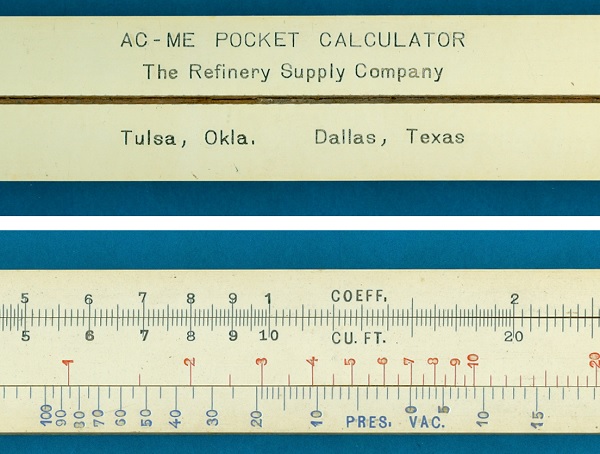

Antique Calculator: The Slide Rule

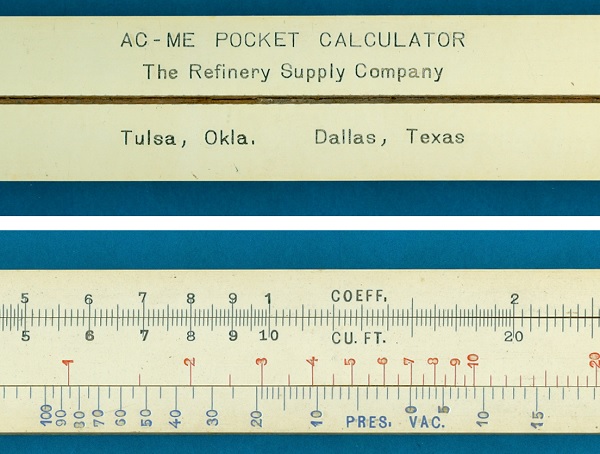

Searching for the history of a Tulsa refining supply company pocket calculator.

David Rance of Sassenheim, Netherlands, has collected a lot of slide rules. Some of the calculators in his collection came from the petroleum industry, including a circa 1950 one made in West Germany for an Oklahoma-based refinery supply company. He seeks any information about it.

An “AC-ME Pocket Calculator,” of the Refinery Supply Company, Tulsa, Oklahoma, preserved by David Rance of the Netherlands.

“I look forward to hearing anything your knowledgeable AOGHS community can tell me about my rather mysterious AC-ME Pocket Calculator,” he optimistically noted in 2016 — see the updated Refinery Supply Company Slide Rule.

Please post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Update: October 28, 2025

Ohio Oil Rush

Exploring Ohio petroleum history from 1885 to about 1930.

Does anyone have recommendations for doing research on the great oil rush of Ohio that occurred from 1885 to ~1930, and peaked in 1897? Are there any good reference books that anyone can recommend? I am trying to research this oil boom and its effect on the construction of an interurban rail connection from Toledo to Lima.

Dave Weber

Also see Oil History Books. Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Update: August 18, 2025

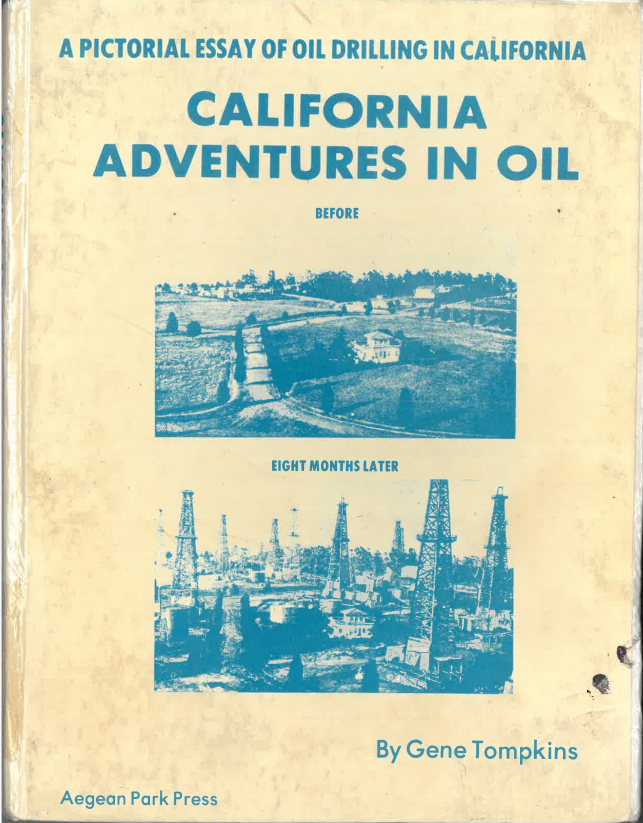

California Adventures in Oil

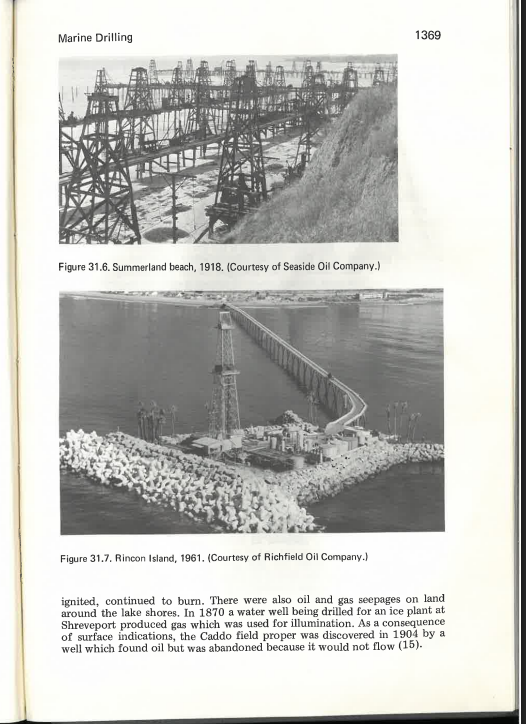

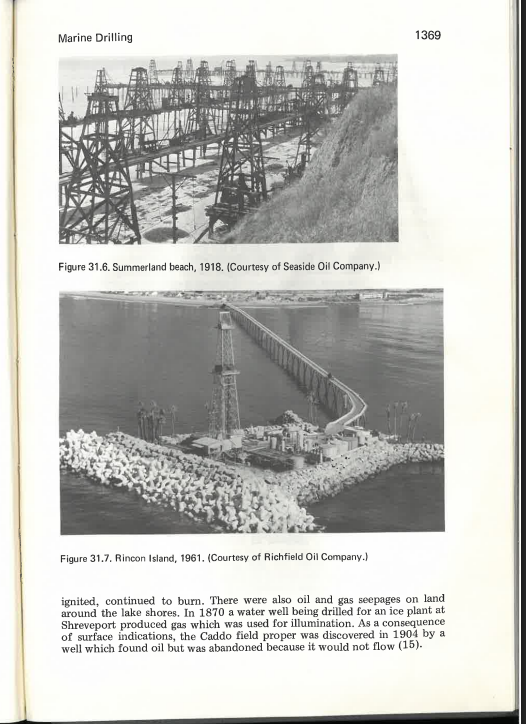

City Planning Associate for Los Angeles shares research resources.I’m a subscriber to your “Oil & Gas History News.” It’s great content to review and learn about the oil industry’s history. I work in Los Angeles on land use/zoning regulations for oil wells in the city, and I’m currently reading a couple of older publications from the public library. Among the images is offshore drilling at the Summerland field that you recently highlighted in your newsletter.

Coastal California oilfields are featured among the 1,500 pages of History of Oil Well Drilling by John E. Brantly.

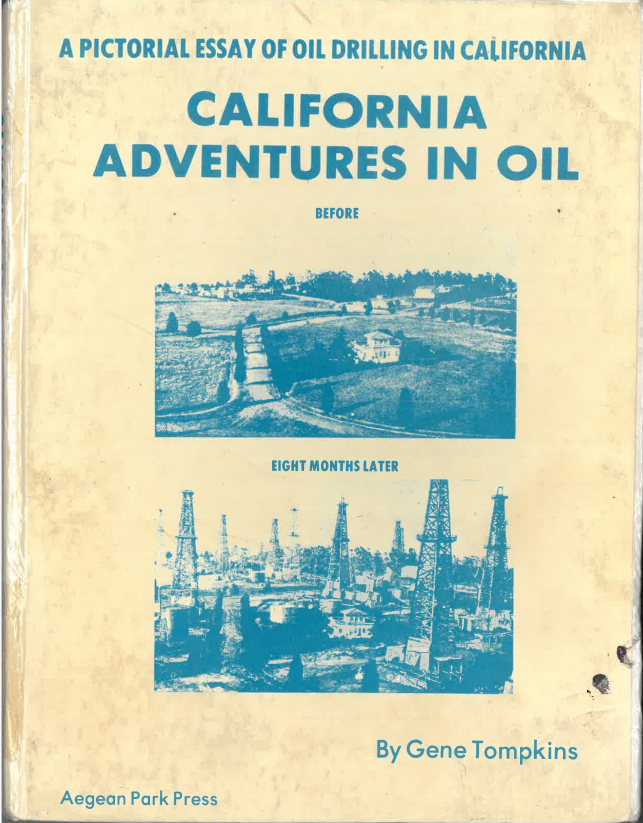

Before retiring as an independent producer in 1963, Eugene Thompkins founded several oilfield service companies, including one that operated at Signal Hill for two decades.

I just thought to share a few PDFs of Summerland photos from History of Oil Well Drilling (1971) by John E. Brantly, pages 1366-1369, and more images from California Adventures in Oil, A Pictorial Essay of Oil Drilling in California (1981) by Gene Tomkins, which might be of interest to your readers. Keep up the great content; much appreciated. — Edber Macedo, City Planning Associate, Office of Zoning Administration, Los Angeles City Planning

Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org

Research Request: July 9, 2025

Desdemona Oil & Refining Company

Editor for International Bond and Share Society seeks source material for circa 1920 Texas company established during the North Texas drilling booms at Electra (1911), Ranger (1917), and Burkburnett (1918).

I’ve been subscribing for a few months and want to thank you for revealing so many obscure technologies and historical artifacts. I collect vintage stocks and bonds (all businesses, not just oil) and have always found it difficult to research these often obscure gas and oil companies. So far, I’ve not been successful in linking a certificate to any of the outfits you’ve mentioned, but it’s just a matter of time.

I recently wrote an article on the Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Co. that was published in the magazine I edit for the International Bond and Share Society, Scripophily. A stock I’ve been trying to research — without much luck — is the Desdemona Oil & Refining Company. If your members have any source material on this outfit, I’d be grateful.

Keep up the good work. — Max Hensley

Please post your reply in the comments section below or email maxdhensley@yahoo.com

Research Request: April 4, 2025

Standard Oil Public Relations Movie

Looking into 1947 film “A Farm In The Valley.”

Hello. My name is Carrie. My family is looking for a film that Standard Oil Company made in Virginia in 1947. It was titled “A Farm In The Valley.” I have several news articles but am looking for the film and/or any information that may be out there as part of the film was filmed on our farm (owned by the Rosen family at the time). I am hoping that maybe your group may have information or contact information for someone who may have information!

— Carrie

Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org

Research Request: November 14, 2024

Looking for The Gargoyle of Mobiloil

Pennsylvania researcher seeks a 1920s company magazine featuring her grandfather, “The Mobiloil King.”

I am in search of a copy of The Gargoyle magazine published by the Vacuum Oil Company from 1923. My great-grandfather, William I. Schreck was proprietor of the Keystone Service Station in Sayre, Pennsylvania, in the 1920’s and was locally dubbed “The Mobiloil King.”

I found an article on Newspapers.com — September 15, 1923 issue of the Sayre Evening Times, which states he was featured in The Gargoyle magazine, with two photos of his service station and an article written by him. I’m guessing it’s maybe the August 1923 or September 1923 issue. Any help locating this would be appreciated!

— Raquel

Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org

Research Request: November 8, 2024

Early Oilfield Production Technology

Artist seeks jerker/shackles for 2026 exhibition.

I am interested in the jerker/shackle lines used in early oil production for an exhibition I am planning for 2026. Does this oilfield equipment (entire assemblies or parts) ever come up for sale or auction? Perhaps there are private collectors or oil museums that might be interested in renting or lending some temporarily?

Best,

Aislinn

Please post your reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org (also see Eccentric Wheels and Jerk Lines).

Research Request: October 7, 2024

Researching Tidewater Oil Company

Researcher from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, seeks more about 1930s publication.

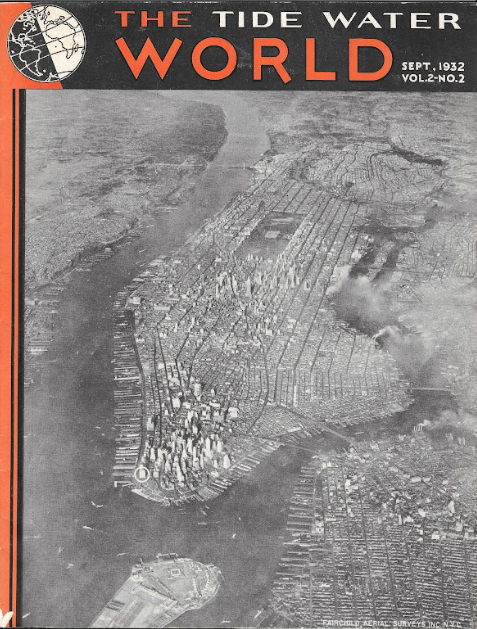

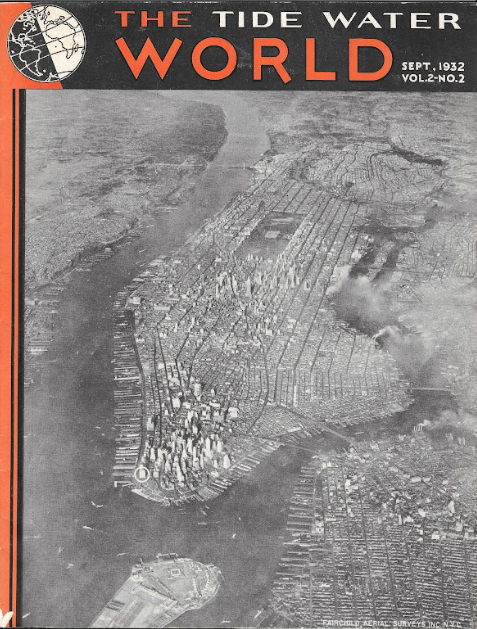

Hello: My grandfather authored an article in “The Tidewater World” in September 1932 (Vol. 2, No. 2). I have one complete issue. He worked in the Research and Development area of Tidewater Oil in Bayonne, New Jersey, 1928-1933.

Founded in 1887 in New York City, Tidewater Oil Company became a major refiner that sold its Tydol brand petroleum products on the U.S. East Coast. Photo courtesy Mark O’Neill.

I am looking for archives who may have additional issues in the series or who has a research focus on Tidewater Oil. Thank you.

— Mark O’Neill

Please call Mark at (717) 803-9918 or post reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: April 20, 2024

Wayne Canada Gasoline Pump

Preserving a rare 1930s Wayne Canada pump.

I recently saved an uncommon Wayne 50A “showcase” gas pump from a metal recycling facility here in Canada. I didn’t have much time for details as it was literally standing in the scrap yard beside the metal chipping machine. I paid the asking price and loaded it into my truck.

Upon arriving home I noticed that the I.D tag was a Wayne Canada, which was a surprise because the odds of it being a Canadian Showcase pump are significantly smaller than American as Canada had far fewer of the 50 and 50A pumps for obvious reasons. The I.D tag got me curious however, as it is stamped 1001-CJXA.

Canadian researcher seeks information about a rare 1930s Wayne Company pump 1001-CJXA.

Is there any way to determine which company ordered this exact gas pump? Is it true that the “1001” number would indicate that this is serial number 1 in Canada for this gas pump? I was told once that Wayne pumps in the 1930s began with the number 100 meaning 100.1 would be serial number 1. I’m not sure if that’s true.

Thanks very much for any help. I’m aware of the pumps rarity and historical significance, hence why I’m trying to find more information on it. Have a great day.

— Jonathan Rempel

Note: The Wayne Oil Tank and Pump Company of Ft. Wayne, Indiana, in 1892 manufactured a hand-cranked kerosene dispenser later converted for gasoline (see Wayne’s Self-Measuring Pump). Primarily Petroleum (oldgas.com) includes research posts with service station histories and gas pump collections; other resources include community oil and gas museums and the Canadian oil patch historians at the Petroleum History Society (PHS).

Please email jrrempel123@gmail.com or post reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: April 20, 2024

Name of Offshore Drilling Rig

Seeking the name of ODECO platform from 1970s.

I’m doing research on my late father, James R. Reese Sr., who worked in the Gulf of Mexico in the early 1970s and into the 1980s, and I’m trying to find the name of a rig he worked on for ODECO. We believe it may have been called the Ocean Endeavour, and we have a photo from my father’s 10th anniversary at the company with “Odeco 7” written on the back. My research points to the Endeavour, but I’m not confident of that. Has anyone heard of the platform and any other name it might have had?

Thank you for any help.

— James Reese Jr.

Note: ODECO (Ocean Drilling & Exploration Company) was founded in 1953. It was acquired by Diamond Offshore Drilling in 1992.

Please email tepapa@hotmail.com or post reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: March 29, 2024

Eastern Oklahoma History

Writer looking to connect petroleum exploration and railroad growth.

I’m writing a memoir that touches on Oklahoma, where I’m from originally, and I would like to learn more about what role did oil and gas exploration played in the expansion of the railroads into the Cherokee Nation in eastern Oklahoma in the late 1800s.

— Dave

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Request: February 22, 2024

Threatt Filling Station on Route 66

Architectural history of potential National Historic Landmark.

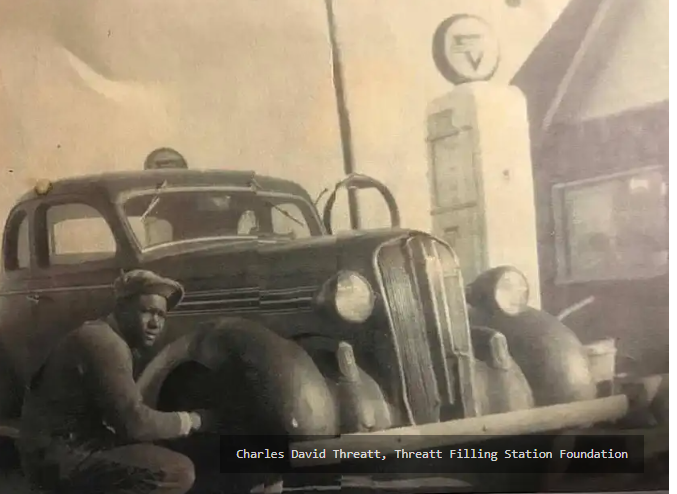

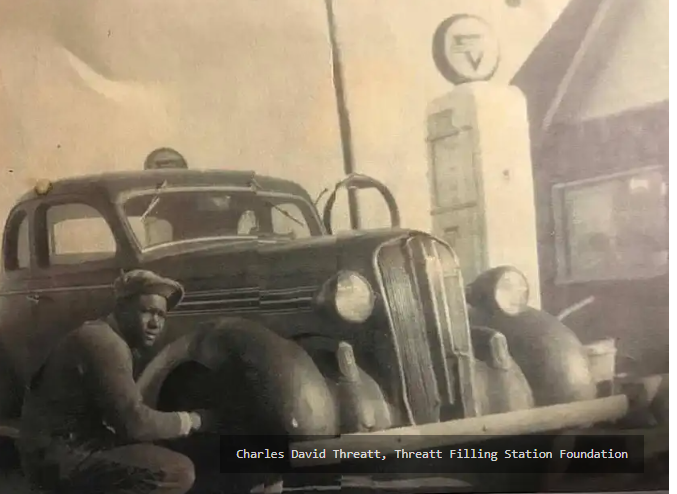

Established in the early 1920s, the Threatt Filling Station in Luther, Oklahoma, is considered the first – and potentially only – African American owned and operated gas station on Route 66. I am under contract with the National Park Service to perform a study to determine whether the the station is eligible to become a National Historic Landmark.

Constructed circa 1915 in Luther, Oklahoma, by Allen Threatt Sr., the Threatt Filling Station sold Conoco products for at least a portion of its many decades of service life, according to the Threatt Filling Station Foundation. Photo courtesy threattfillingstation.org.

What I am looking for is an Oklahoma contact, who has knowledge of the history of gas-oil distribution in the Sooner State in the 1920s-40s period. It appears that at one point, the Threatts were associated with Conoco. I would like to better understand how those supply-branding operations worked and whether there is historical paperwork that would cover this station.

Any assistance will be appreciated. Thank you,

— John

Please email john@archhistoryservices.com or post reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: January 2, 2024

Oil Refinery and R.R. Trackside Building Photos

Model railroader seeks detailed images of facilities in Santa Fe Springs and Los Angeles.

Thank you for sharing most interesting and valuable information. I use your society to help me with prototype research for my model railroading.

I am looking for information on the Powerine Oil Refinery at Santa Fe Springs circa 1950s and the trackside Hydril Oil Field Equipment buildings on approach to Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal, and photos and dimensions of buildings/building interiors for model railroading purposes.

A model railroad scene of the southern California petroleum industry in the 1950s includes oil derricks, “each with an operating horsehead style oil pump underneath.”

Justin Mitchell has recreated trackside oilfield derricks at Santa Fe Springs and researched oilfield engine audio files, “so I can add sound to the layout to match the operating pumps.”

The Powerine Oil Refinery at Santa Fe Springs closed in 1995. Skilled model railroaders prize detail and historical accuracy.

Best regards from Sydney, Australia

— Justin Mitchell

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Request: December 26, 2023

Cities Service in Wichita

Seeking service station photos.

I am looking for photographs of a Cities Service Station located at 610 N. Seneca Street in Wichita, Kansas, in the 1950s, maybe early 60s. I have my father’s business card from that station. I remember the service station even though I was only 4 years old. Any assistance is greatly appreciated.

— Pamela

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Request: September 25, 2023

Circa 1930 Driller from Netherlands

From a researcher investigating a great-great uncle’s role in the Texas oil patch.

A family history researcher in the Netherlands seeks help adding to her limited information about a great-great uncle who worked for J. Barry Fuel Oil Company in Texas oilfields from the 1920s to the early 1930s. The petroleum-related career of Ralph “Dutch” Weges included traveling on an early oil tanker later sunk during World War I.

Learn more and share research in Driller from Netherlands.

Research Request: July 13, 2023

How and Where Standard Oil produced Naphtha

From a writer working on a history of the lighting of New York City.

In the late 19th century, Standard Oil gained control of all of the gas lighting companies in New York. My understanding is that they did so in part because the gas companies at the time produced something called water gas, which relied on the use of naphtha, and Standard Oil produced almost all of the naphtha in the United States.

How and where Standard Oil produced its naphtha around 1890-1900 and how it would have transported it to the NYC gas companies? Would it have been produced in the Midwest and shipped east by pipeline? Railcar? Did they ship crude oil east and refine it into naphtha somewhere on the East Coast?

Also, any suggestions for where I could find info on how much naphtha Standard Oil produced around that time and, perhaps, how much of it was shipped to New York? I have looked in all the standard histories and tried every Google and newspaper searches. Can anyone offer suggestions? Thanks very much.

— Mark

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Reply

August 26, 2023, from Reference Services, American Heritage Center

The American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming does hold a set of records for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, 1874-1979. The online guide is posted here. This is one of our older guides not yet converted to the online format, and it includes many handwritten notes about the removal of items from this manuscript collection to other collections.

— American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

Research Request: June 23, 2023

Houston Petrol Filler

From an Australian “petrol bowser” researcher

I recently came across this brass fitting which is clearly marked THE HOUSTON PETROL FILLER Pat 1307. The patent number is extremely early. I am assuming it is part of an early petrol pump or as we call them here in Australia, a petrol bowser. Is there any chance anyone can identify what this was originally part of. Many thanks for your help. Regards.

— Justin

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Reply

October 18, 2023 (also from Australia)

Hello Justin,

I have one of these that has turned up in my late father’s stuff. Identical to yours except for the screwed end which has a strangely shaped protrusion. I’ll send you a pic if you are interested. Did you ever find out anything about it? I’m looking for somewhere to donate it — where it will be appreciated.

Regards, David

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Research Request: April 12, 2023

Information about Wooden Barrel

From researcher who has a barrel with a red star and

I have got this old oil barrel. I’m trying to find out more information about it. I’m guessing around the 1920’s but I really have no clue. I was hoping someone there could shed some light on it. I’m not interested in selling it just some information. Much appreciated!

— Robert

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Reply

November 25, 2023

To Robert,

Your wood barrel is clearly “The Texas Company” (i.e., Texaco) container for “Petroleum Products.” Except for the red star with big green T, the rest of the lithography on your barrel is harder to interpret. My source for reference is Elton N. Gish’s self-published 2003 book Texaco’s Port Arthur Works. Unfortunately, the book does not have an index, but it has a lot of company photographs in it surrounded by narratives. Most of the photos of product containers are for metal cans and drums, but one group photo of a product display dated 1932 shows wood barrels still in use although metal drums predominate by that time. The only wood barrels discussed by Gish are for “slack barrels” used for asphalt, and it looks like you have some asphalt residue on your barrel top. Gish indicates that the “Red star-green T” trademark lithography began to be used by 1909 and continued to be used to present in various renditions, but a 1920s date range for you barrel seems reasonable. I hope this helps.

— Andy

Research Request: September 3, 2022

Identifying a Circa 1915 Gas Pump

From the lead mechanic at San Diego Air & Space Museum

I’m hoping someone visiting the American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s website can help me identify the gas pump we are restoring here at the San Diego Air and Space Museum. I believe it’s a Gilbert and Barker from 1915 or so.

The data plate is missing and I’ve been having trouble finding a similar one in my online search. Thanks!

— Gary Schulte, Lead Mechanic, SDASM

Please email Gary engshop@sdasm.org or post your reply in the comments section below.

Learn more history about early kerosene and gasoline pumps in First Gas Pump and Service Station; a collector’s rare 1892 pump in Wayne’s Self-Measuring Pump; and the 24-hour Gas-O-Mat in Coin-Operated Gas Pumps.

Research Request: August 11, 2022

Gas Streetlights in the Deep South

From a professor, author and “history detective”

I am doing historical research on gas streetlights in the Deep South. Any suggestions will be much appreciated. My big problem at the moment is Henry Pardin. He bought the patent rights to a washing machine in Washington, DC, in 1856 and was in Augusta, Georgia, in 1856. Pardin set up gas streetlights in Baton Rouge, Holly Springs, Natchez, and Shreveport in 1857-1860. I have failed to find him in any of the standard research sources.

Any help on gas street lights in the south before the Civil War is appreciated. Thank you for your time.

— Prof. Robert S. “Bob” Davis, Blountsville, Alabama, Genws@hiwaay.net

Please email Bob or post your reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: August 5, 2022

Drop in Stop Action Film

From a stop action film researcher:

“Your website is doing good things for education. It is a gold mine for STEM high school teachers — and also for people like me, who like stop motion oil industry films, Bill Rodebaugh noted in an August 2022 email to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

Researcher seeks the origin of stop action film (oil?) drops.

Rodebaugh, who has researched many stop motion archives (including AOGHS links at Petroleum History Videos), seeks help finding the source of an unusual character — a possible oil drop with a face and arms. The purpose of the figures remains unknown.

“I am discouraged about finding that stop motion film, because I have seen or skimmed through many of those industry films, which are primarily live action,” Rodebaugh explained. He knows the puppet character is not from the Shell Oil educational films, “Birth of an Oil Field” (1949) or “Prospecting for Petroleum” (1956). He hopes a website visitor can assist in identifying the origin of the hand-manipulated drops. “I am convinced that if this stop motion film can be found, it would be very interesting.”

— Bill Rodebaugh, brodebaugh@suddenlink.net

Please email Bill or post your reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: July 2022

Gas Station Marketplace History

From an automotive technology writer:

I’m looking for any information on the financial environment during the early days of the automotive and gasoline station industry. The idea is to compare and contrast the market-driven forces back then to the potential for government subsidies/investments etc. to pay for electric vehicle charging stations today.

At this point, I have not found any evidence but I wanted to be thorough and ask the petroleum history community. From what I have seen, gas stations were funded privately by petroleum companies and their investors and shareholders.

I’m not talking about gas station design or the impact on the nation/communities, but the market forces behind the growth of the industry. Please let me know of any recommended sources. I have already read The Gas Station in America by Jackie & Sculle.

— Gary Wollenhaupt, gary@garywrites.com

Please email Gary or post your reply in the comments section below.

Research Request: April 2022

Seeking Information about Doodlebugs

From a Colorado author, consulting geologist and engineer:

I am trying to gather information on doodlebugs, by which I mean pseudo-geophysical oil-finding devices. These could be anything from modified dowsing rods or pendulums to the mysterious black boxes. Although literally hundreds of these were used to search for oil in the 20th century, they seem to have almost all disappeared, presumably thrown out with the trash. If anyone has access to one of these devices, I would like to know.

— Dan Plazak

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org. Dan Plazak is a longtime AOGHS supporting member and a contributor to the historical society’s article Luling Oil Museum and Crudoleum.

Research Request: February 2022

Know anything about W.L. Nelson of University of Tulsa?

From an associate professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts:

I am doing research on the role of the University of Tulsa in the education of petroleum refining engineers and in particular am seeking information about a professor who taught there named W.L. Nelson, author of the textbook Petroleum Refinery Engineering, first published in 1936. He taught at Tulsa until at least the early 1960s. He was also one of the founders of the Oil and Gas Journal and author of the magazine’s “Q&A on Technology” column. If anyone has any leads for original archival sources by or about Nelson and UT, I would appreciate hearing from you.

Thank you and best wishes, M.G.

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Emailed response to “Seeking Information about W.L. Nelson of University of Tulsa.”

My late father was a 1943 graduate of the University of Tulsa with a degree in petroleum engineering with an emphasis in refining. By the time my late uncle graduated in 1948, his degree had become chemical engineering with an emphasis in refining. Both had high regard for Wilbur L. Nelson. Both had long careers in the refining at Murphy Oil Corporation and Sun Oil Company. My father would pass along to me his obsolete Petroleum Refinery Engineering, as Nelson periodically updated his book. I will check my father’s papers for any Nelson relics. Let me know how your inquiry goes.

— Professional Engineer, El Dorado, Arkansas

————————

Oil History Forum

Research requests from 2021:

Star Oil Company Sign

Looking for information about an old porcelain sign from the Star Oil Company of Chicago.

Learn more in Seeking Star Oil Company.

Bowser Gas Pump Research

I have a BOWSER, pump #T25988; cut #103. This is a vintage hand crank unit. I can’t seem to find any info on it! Any help would be appreciated, Thank You. (Post comments below) — Larry

Hand-cranked Bowser Cut 103 Pump.

Originally designed to safely dispense kerosene as well as “burning fluid, and the light combustible products of petroleum,” early S.F. Bowser pumps added a hose attachment for dispensing gasoline directly into automobile fuel tanks by 1905. See First Gas Pump and Service Station for more about these pumps and details about Bowser’s innovations.

Bowser company once proclaimed its “Cut 103” as “the fastest indoor gasoline gallon pump ever made” with an optional “hose and portable muzzle for filling automobiles.”

Collectors’ sites like Oldgas.com offer research tips for those who share an interest in gas station technological innovations.

Circa 1900 California Oilfield Photo

My grandfather worked the oilfields in California in the early 1900’s.

He worked quite a bit in Coalinga and also Huntington Beach. He had this in his old pictures. I would like to identify it if possible. The only clue that I see is the word Westlake at the bottom of the picture. What little research I could do led me to believe it might be the Los Angeles area?

I would appreciate any help you can provide. (Post comments below.) — B.

Cities Service Bowling Teams and Oil History

I was wondering if there are any records or pictures of bowling leagues and teams for Cities Service in the late 1950s and early 1960s in Houston, Texas, or Lafayette, Louisiana. I would appreciate any information. My dad was on the team. (Post comments below.) — Lisa

Oilfield Storage Tanks

My family has a farm in western PA and once had a small oil pump on the land. I’m trying to learn how the oil was transported from the pump. I know a man came in a truck more than once each week to turn on the pump and collect oil, but I don’t know if there was a holding tank, how he filled his truck, etc. (My mother was a child there in the ’40s and simply can’t recall how it all worked.) Can anyone point me at a resource that would explain such things? I’m working on a children’s book and need to get it right. Thank you. — (Post comments below.) Lauren

Author seeking Historical Oil Prices

Can anyone at AOGHS tell me what the ballpark figures are in the amount of petroleum products so far extracted, versus how much oil-gas is left in the world? Also: the price per barrel of oil every decade from the 1920s to the present. And the resulting price per gallon during the decades from 1920 to the present year? I have almost completed my book about an independent oilman. Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

— John

Painting related to Standard Oil History

I am researching an old oil painting on canvas that appears to be a gift to Esso Standard Corp. Subject: Iris flowers. There is some damage due to age but it is quite interesting. The painting appears to be signed in upper right corner: Hirase?

On the back, along each side, is Japanese writing that I think translates to “Congratulations Esso Standard” and “the Tucker Corporation” or “the Naniwa Tanker Corporation.” Date unknown, possibly 1920s.

I am not an expert in art nor Japanese culture, so some of my translation could be incorrect. I was hoping you or your colleagues might shed some light on this painting.

— Nancy

Please post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Early Gasoline Pumps

For the smaller, early stations from around 1930, was the gas stored in a tank in the ground below the dispenser/pump? — Chris Please ad comment below.

Oilfield Jet Engines

I was wondering about a neat aspect of oil and natural gas production; namely, the use of old, retired aircraft jet engines to produce power at remote oil company locations, and to pump gas/liquid over long distances in pipelines. Does anyone happen to recall what year a jet engine was first employed by the industry for this purpose? Nowadays, there is an interesting company called S&S Turbine Services Ltd. (based at Fort St. John, British Columbia) that handles all aspects of maintenance, overhaul and rebuilding for these industrial jets.

— Lindsey

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Natalie O. Warren Propane Tanker Memorabilia

My father spent his working life with Lone Star Gas, he is gone many years now I am getting on. Going through a few of his things. A little book made up that he received when he and my mother attended the commissioning of the Natalie O. Warren Propane Tanker. I am wondering if it is of any value to anyone. Or any museum.

— Bill

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Elephant Advertising of Skelly Oil

My grandfather owned a Skelly service station in Sidney, Iowa in the 1930s and 1940s. I have a photo of him with an elephant in front of the station. I recall reading somewhere that Skelly had this elephant touring from station to station as an advertising stunt. Does anyone have any more history on the live elephant tour for Skelly Oil? I’d love to find out more. — Jeff Please ad comment below.

Tree Stumps as Oilfield Tools

I am a graduate student at the Architectural Association in London working on a project that looks at the potential use of tree stumps as structural foundations. While researching I found the following extract from an article on The Petroleum Industry of the Gulf Coast Salt Dome Area in the early 20th century: “In the dense tangle of the cypress swamp, the crew have to carry their equipment and cut a trail as they go. Often they use a tree stump as solid support on which they set up their instruments.” I have been struggling to find any photos or drawings of how this system would have worked (i.e. how the instruments were supported by the stump) I was wondering if you might know where I could find any more information?

— Andrew

Post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Texas Road Oil Patch Trip

“Hi, next year we are planning a road trip in the United States that starts in Dallas, Texas, heading to Amarillo and then on to New Mexico and beyond. We will be following the U.S. 287 most of the way to Amarillo and would like to know of any oil fields we could visit or simply photograph on the way. From Amarillo we plan to take the U.S. 87. We realise this is quite a trivial request but you help would be much appreciated.”

— Kristin

Please post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

Antique Calculator: The Slide Rule

Here’s a question about those analog calculating devices that became obsolete when electronic pocket calculators arrived in the early 1970s…Learn more in Refinery Supply Company Slide Rule.

Please post oil history forum replies in the comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

—————

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. Contact the society at bawells@aoghs.org if you would like a research question added. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

.