Thousands of offshore petroleum structures provide energy — and marine habitats.

Offshore petroleum platforms act as artificial reefs, creating important marine habitats, according to scientists. Beginning with an Exxon experimental subsea structure in 1979, the U.S. government’s “Rigs to Reefs” program established the largest artificial habitat in the world.

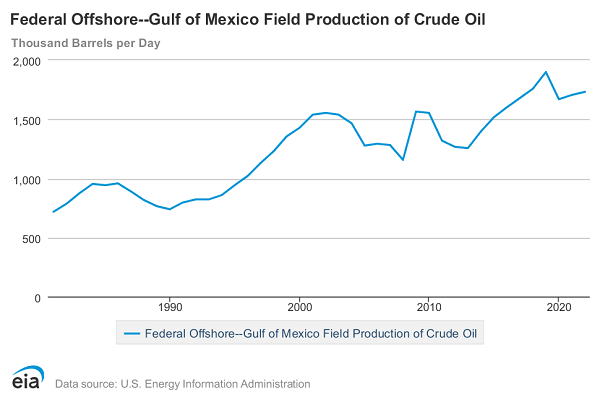

The Gulf of Mexico, both onshore and offshore, has continued to be a key contributor to U.S. oil and natural gas resources and energy infrastructure. Federal offshore oil production in 2023 accounted for 15 percent of total U.S. crude oil and five percent of natural gas production, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Offshore platforms make good artificial reefs. The open design attracts fish — and divers — where they can swim easily through the circulating water. Photo courtesy U.S. Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

“Over 47 percent of total U.S. petroleum refining capacity is located along the Gulf coast, as well as 51 percent of total U.S. natural gas processing plant capacity,” the federal agency added. With annual U.S. crude oil demand climbing (19.1 million barrels of oil a per day in 2022), offshore Gulf production almost doubled since the 1980s.

With about 4,500 petroleum-related platforms offshore, EIA also noted the drilling and production structures have benefited both the economy and the marine environment — even with disastrous offshore accidents, including (Santa Barbara (1969), Exxon Valdez (1989), and Deepwater Horizon (2010). Improved mitigation efforts have been hard earned.

New Marine Environments

In 1984, Congress established the National Fishing Enhancement Act, “because of increased interest and participation in fishing at offshore oil and gas platforms and widespread support for effective artificial reef development by coastal states,” according to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

The fishing enhancement legislation led to the National Artificial Reef Plan for turning old rigs into reefs. The act established national artificial reef standards as the Minerals Management Service (MMS) developed policies encouraging the reuse of obsolete offshore petroleum structures.

MMS — the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) in 2011 — required compliance with standards of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and criteria in the National Artificial Reef Plan of 1985. States were given authority to plan, construct, and manage artificial reefs.

Although Rigs to Reefs developed as an official policy in the mid-1980s, the concept was first explored in 1979. The National Artificial Reef Plan led to development of government-endorsed artificial reef projects.

The first planned conversion took place in 1979 with the re-location of an Exxon experimental subsea structure from offshore Louisiana to an artificial reef site off Apalachicola, Florida.

A typical four-pile platform provides almost three acres of living and feeding habitat for thousands of species. Photo courtesy U.S. Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

Rigs to Reefs was designed to utilize offshore structures that were no longer producing, allowing them to remain in the marine environment. The result has been the creation of the largest artificial reef complex in the world.

Scientists have proclaimed the industry-government partnership in the Gulf of Mexico as a success story.

Thousands of Fish Habitats

Petroleum platforms are artificial habitats. Whether placed as an artificial reef or a working (producing petroleum) structure, they have been found to increase the algae and invertebrates that attract and significantly increase the numbers and species of fish.

However, when an offshore structure becomes obsolete, it typically is removed from the environment, taking away the habitat that it created and disrupting those organisms residing at the site.

To prevent this disruption, the Rig to Reefs program allows oil and natural gas companies to choose to donate the reef to a coastal state — using one of three methods: tow-and-place, topple-in-place, or partial removal.

According to Ocean Science (an MMS publication), the program benefits petroleum platform owners by eliminating the high cost of transporting the structure for disposal. States benefit as the retired platform develops into an area that enhances commercial and recreational fishing, tourism, and the biological community.

The marine populations that result from the recycled structures are called platform communities. Fish densities have been found to be 20 to 50 times higher than in open water. Each platform typically has supported more than 10,000 fish.

In addition, the platforms have become home to many other forms of sea life; barnacles, and mussels dwell on the hard surfaces, and sea turtles are often found close by, according to marine scientists. One result is a complex food chain formed in environments that did not previously have characteristics to support natural reef communities.

Good Fishing

Seventy-five percent of recreational fishing trips in Louisiana visit one or more rig sites. These platforms are an ideal choice for artificial reefs. The structures’ size, density and open design attract fish to the structures where they can swim easily through the circulating water. Stable during storms, the steel provides the hard surface needed to create coral communities.

Coastal states benefit from offshore platforms: Seventy-five percent of recreational fishing trips in Louisiana visit one or more rig sites — for the excellent fishing.

To study life at artificial reef corals, federal agencies work with universities, including the Coastal Marine Institute (CMI) at Louisiana State University. Scientists also have been looking at the ecological effects of removing large numbers of petroleum structures.

In California, the populations of fish living in platform communities are the subject of several research projects. With many areas overfished, the increased population of fish at artificial reefs could be valuable.

Working with the petroleum platforms in the Gulf of Mexico has set a good example, especially for those who like to fish at them. “The fishing here is spectacular, whether it’s snapper, amberjack or grouper,” proclaimed charter boat Capt. Kerry Milano of Venice, La.

“There’s really no limit to what you can catch at these offshore platforms,” the skipper added, “This is some of the best fishing anywhere in the world.”

Article adapted from Ocean Science, March 2008, a quarterly magazine resource for ocean science and offshore technological information. Learn more at the BSEE’s Offshore Stats and Facts.

Overfished Species Habitat

Whether it is an operating production platform or a retired rig intentionally placed, a typical four-pile, platform jacket provides almost three acres of living and feeding habitat for thousands of underwater species. That’s beneficial for marine life, according to marine biologists, because the natural bottom of the Gulf of Mexico is a flat plain, comprised of mud, clay and sand with very little natural rock bottom and reef habitat.

A June 2006 report by marine scientists at the University of California, Santa Barbara, demonstrates that California’s offshore oil and natural gas platforms are critical nursery habitats for a certain species of fish.

Scientists argue that offshore oil platforms should be protected to help revitalize the Bocaccio rockfish population.

According to scientists, platforms play an important role in producing the young of a rockfish species on a scale that was previously unknown. The findings have the potential to cause a significant shift in conventional thinking regarding artificial reefs.

“This will have a huge impact on how we view these structures,” noted George Steinbach, executive director of the California Artificial Reef Enhancement Program. “These platforms are better nursery habitat than the natural reefs in the area. They are contributing to the recovery of a severely depleted species in a significant way.”

Dr. Milton Love and his team of researchers found that the number of young Bocaccio rockfish around only eight platforms in the Santa Barbara Channel amounted to 20 percent of the average number found over the species’ entire range. The federal government classified the Bocaccio as “overfished” by commercial fleets.

According to Don Kent, president of Hubbs SeaWorld Research Institute (HSWRI), founded in 1963. “When 20 percent of the next generation of Bocaccio for the entire West Coast is found in such a small area, you cannot ignore the importance of that area as habitat.”

Tom Raftican, president of United Anglers of Southern California, added that with the fishing data, “it’s clear that these platforms should also be protected to help revitalize the Bocaccio rockfish population.”

With facilities in San Diego and Carlsbad, California, and Melbourne Beach, Florida, the institute seeks “objective scientific solutions to challenges threatening ocean health and marine life.”

Learn more about petroleum offshore history and exploration technologies in Deep Sea Roughnecks and ROV — Swimming Socket Wrench.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Rigs-to-reefs: the use of obsolete petroleum structures as artificial reefs (1987); Offshore Pioneers: Brown & Root and the History of Offshore Oil and Gas

(1997); The Offshore Imperative: Shell Oil’s Search for Petroleum in Postwar America

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Rigs to Reefs.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/offshore-history/rigs-to-reefs/. Last Updated: March 1, 2025. Original Published Date: June 1, 2008.