Government scientists experimented with atomic blasts to fracture natural gas wells.

Project Gasbuggy was the first in a series of Atomic Energy Commission downhole nuclear detonations to release natural gas trapped in shale. This was “fracking” late 1960s style.

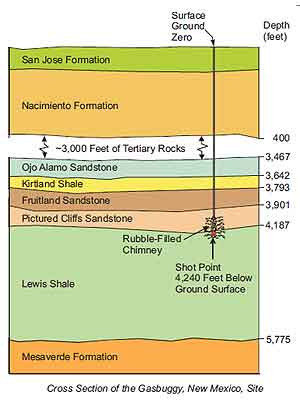

In December 1967, government scientists — exploring the peacetime use of controlled atomic explosions — detonated Gasbuggy, a 29-kiloton nuclear device they had lowered into an experimental well in rural New Mexico. The Hiroshima bomb of 1945 was about 15 kilotons.

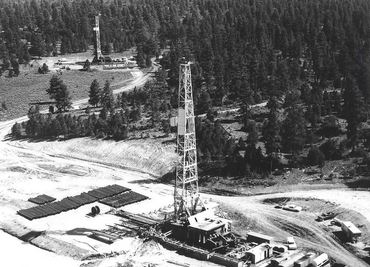

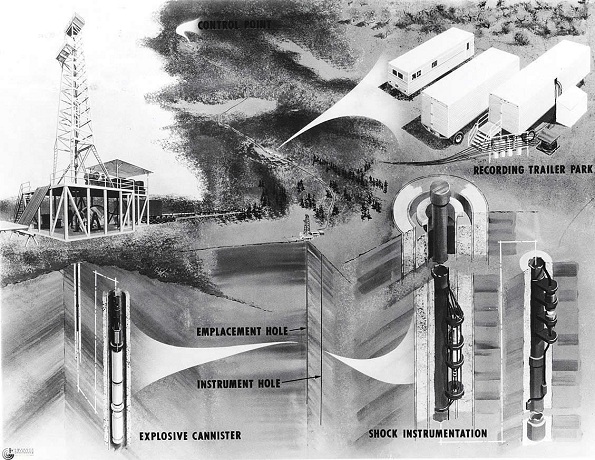

Scientists lowered a 13-foot by 18-inch diameter nuclear device into a New Mexico gas well. The experimental 29-kiloton Project Gasbuggy bomb was detonated at a depth of 4,240 feet. Photo courtesy Los Alamos Lab.

The Project Gasbuggy team included experts from the Atomic Energy Commission, the U.S. Bureau of Mines, and El Paso Natural Gas Company. They sought a new, powerful method for fracturing petroleum-bearing formations.

Near three low-production natural gas wells, the team drilled to a depth of 4,240 feet — and lowered a 13-foot-long by 18-inch-wide nuclear device into the borehole.

Plowshare Program: Peaceful Nukes

The 1967 experimental explosion in New Mexico was part of a wider set of experiments known as Plowshare, a program established by the Atomic Energy Commission in 1957 to explore the constructive use of nuclear explosive devices.

“The reasoning was that the relatively inexpensive energy available from nuclear explosions could prove useful for a wide variety of peaceful purposes,” noted a report later prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy.

From 1961 to 1973, researchers carried out dozens of separate experiments under the Plowshare program — setting off 29 nuclear detonations. Most of the experiments focused on creating craters and canals. Among other goals, it was hoped the Panama Canal could be inexpensively widened.”

In the end, although less dramatic than nuclear excavation, the most promising use for nuclear explosions proved to be for stimulation of natural gas production,” explained the September 2011 government report.

Detonated 60 miles from Farmington in 1967, the first nuclear detonation created a “Rubble Filled Chimney,” producing 295 million cubic feet of natural gas — and deadly Tritium radiation.

Tests, mostly conducted in Nevada, also took place in the petroleum fields of New Mexico and Colorado. Project Gasbuggy was the first of three nuclear fracturing experiments that focused on stimulating natural gas production. Two later tests took place in Colorado.

Atomic Energy Commission scientists worked with experts from the Astral Oil Company of Houston, with engineering support from CER Geonuclear Corporation of Las Vegas.

The experimental wells, which required custom drill bits to meet the hole diameter and narrow hole deviation requirements, were drilled by Denver-based Signal Drilling Company or its affiliate, Superior Drilling Company.

Projects Rulison and Rio Blanco

In 1969, Project Rulison, the second of the three nuclear well stimulation projects, blasted a natural gas well near Rulison, Colorado. Scientists detonated a 43-kiloton nuclear device almost 8,500 feet underground to produce commercially viable amounts of natural gas.

In 1973, another fracturing experiment at Rio Blanco, northwest of Rifle, Colorado, was designed to increase natural gas production from low-permeability sandstone.

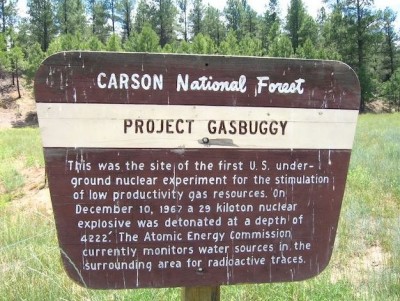

Gasbuggy: “Site of the first United States underground nuclear experiment for the stimulation of low-productivity gas reservoirs.” Photo Courtesy DOE.

The May 1973 Rio Blanco test consisted of the nearly simultaneous detonation of three 33-kiloton devices in a single well, according to the Office of Environmental Management. The explosions occurred at depths of 5,838, 6,230, and 6,689 feet below ground level. It would prove to be the last experiment of the Plowshare program.

Although a 50-kiloton nuclear explosion to fracture deep oil shale deposits — Project Bronco — was proposed, it never took place. Growing knowledge (and concern) about radioactivity ended these tests for the peaceful use of nuclear explosions. The Plowshare program was canceled in 1975.

After an examination of all the nuclear test projects, the U.S. Department of Energy September 2011 reported:

By 1974, approximately 82 million dollars had been invested in the nuclear gas stimulation technology program (i.e., nuclear tests Gasbuggy, Rulison, and Rio Blanco). It was estimated that even after 25 years of gas production of all the natural gas deemed recoverable, only 15 to 40 percent of the investment could be recovered. At the same time, alternative, non-nuclear technologies were being developed, such as hydrofracturing.

DOE concluded, Consequently, under the pressure of economic and environmental concerns, the Plowshare Program was discontinued at the end of FY 1975.

Project Gasbuggy: Nuclear Fracking

“There was no mushroom cloud, but on December 10, 1967, a nuclear bomb exploded less than 60 miles from Farmington,” explained historian Wade Nelson in an article written three decades later, “Nuclear explosion shook Farmington.”

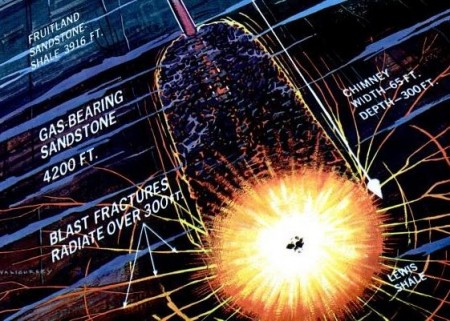

Government scientists believed a nuclear device would provide “a bigger bang for the buck than nitroglycerin” for fracturing dense shales and releasing natural gas. Illustration courtesy Los Alamos Lab.

The 4,042-foot-deep detonation created a molten glass-lined cavern about 160 feet in diameter and 333 feet tall. It collapsed within seconds. Subsequent measurements indicated fractures extended more than 200 feet in all directions — and significantly increased natural gas production.

A September 1967 Popular Mechanics article described how nuclear explosives could improve previous fracturing technologies, including gunpowder, dynamite, TNT — and fractures “made by forcing down liquids at high pressure.”

Hydraulic fracturing technologies pump a mixture of fluid and sand down a well at extremely high pressure to stimulate production of oil and natural gas wells.

The first commercial application of hydraulic fracturing took place in March 1949 near Duncan, Oklahoma, following experiments in a Kansas natural gas field. Increasing oil production by fracturing geologic formations had begun about a century earlier (see Shooters – A “Fracking” History).

A 1967 illustration in Popular Mechanics magazine showed how a nuclear explosive would improve earlier technologies by creating bigger fractures and a “huge cavity that will serve as a reservoir for the natural gas.”

Scientists predicted that nuclear explosives would create more and bigger fractures “and hollow out a huge cavity that will serve as a reservoir for the natural gas” released from the fractures.

“Geologists had discovered years before that setting off explosives at the bottom of a well would shatter the surrounding rock and could stimulate the flow of oil and gas,” Nelson explained. “It was believed a nuclear device would simply provide a bigger bang for the buck than nitroglycerin, up to 3,500 quarts of which would be used in a single shot.”

The first 1967 underground detonation test was part of a broader federal program begun in the late 1950s to explore the peaceful uses of nuclear explosions.

“Today, all that remains at the site is a plaque warning against excavation and perhaps a trace of tritium in your milk,” Nelson added in his 1999 article. He quoted James Holcomb, the site foreman for El Paso Natural Gas, who saw a pair of white vans that delivered pieces of the disassembled nuclear bomb.

“They put the pieces inside this lead box, this big lead box…I (had) shot a lot of wells with nitroglycerin and I thought, ‘That’s not going to do anything,” reported Holcomb. A series of three production tests, each lasting 30 days, was completed during the first half of 1969. Government records indicated the Gasbuggy well produced 295 million cubic feet of natural gas.

“Nuclear Energy: Good Start for Gasbuggy,” proclaimed the December 22, 1967, TIME magazine. The Department of Energy, which had hoped for much higher production, determined that Tritium radiation contaminated the gas. It flared — burned off — the gas during production tests that lasted until 1973. Tritium is a naturally occurring radioactive form of hydrogen.

A 2012 Nuclear Regulatory Commission report noted, “Tritium emits a weak form of radiation, a low-energy beta particle similar to an electron. The tritium radiation does not travel very far in air and cannot penetrate the skin.”

A plaque marks the site of Project Gasbuggy in the Carson National Forest, 90 miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico.

According to Nelson, radioactive contamination from the flaring “was minuscule compared to the fallout produced by atmospheric weapons tests in the early 1960s.” From the well site, Holcomb called the test a success. “The well produced more gas in the year after the shot than it had in all of the seven years prior,” he said.

In 2008, the Energy Department’s Office of Legacy Management assumed responsibility for long-term surveillance and maintenance at the Gasbuggy site. A marker placed at the Gasbuggy site by the Department of Energy in November 1978 reads:

Site of the first United States underground nuclear experiment for the stimulation of low-productivity gas reservoirs. A 29 kiloton nuclear explosive was detonated at a depth of 4227 feet below this surface location on December 10, 1967. No excavation, drilling, and/or removal of materials to a true vertical depth of 1500 feet is permitted within a radius of 100 feet of this surface location. Nor any similar excavation, drilling, and/or removal of subsurface materials between the true vertical depth of 1500 feet to 4500 feet is permitted within a 600 foot radius of t 29 n. R 4 w. New Mexico principal meridian, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico without U.S. Government permission.

USSR’s Project NEVA

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) responded with its own more extensive program in 1965, according to a declassified 1981 Central Intelligence Agency report.

The CIA assessment, “The Soviet Program for Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Explosions,” reported that by the mid-1970s, the Soviets had detonated nine nuclear devices in seven Siberian fields to increase natural gas production as part of Project NEVA – Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy.

The USSR atomic tests delivered essentially the same conclusion as did America’s Project Gasbuggy – no commercially feasible petroleum production — and not popular with the public because of environmental concerns. The USSR abandoned Project NEVA experiments in 1989, more than a decade after the end of America’s Plowshare program.

Parker Drilling Rig No. 114

In 1969, Parker Drilling Company signed a contract with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to drill a series of holes up to 120 inches in diameter and 6,500 feet in depth in Alaska and Nevada for additional nuclear bomb tests. Parker Drilling’s Rig No. 114 was one of three special rigs built to drill the wells.

Parker Drilling Rig No. 114 was among those used to drill wells for nuclear detonations and later modified to drill conventional, very deep wells. Since 1991, the 17-story rig has welcomed visitors to Elk City, Oklahoma, next to the shuttered Anadarko Museum of Natural History. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Founded in Tulsa in 1934 by Gifford C. Parker, by the 1960s Parker Drilling had set numerous world records for deep and extended-reach drilling.

According to the Baker Library at the Harvard Business School, the company “created its own niche by developing new deep-drilling technology that has since become the industry standard.”

Following completion of the nuclear-test wells, Parker Drilling modified Rig No. 114 and its two sister rigs to drill conventional wells at record-breaking depths.

After retiring Rig No. 114 from oilfields, Parker Drilling in 1991 loaned it to Elk City, Oklahoma, as an energy education exhibit next to the Anadarko Museum of Natural History, which later closed. The 17-story rig has remained there to welcome Route 66 and I-40 travelers.

Learn about drilling miles deep in Anadarko Basin in Depth.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Atoms for Peace and War 1953-1961 (2017); Project Plowshare: The Peaceful Use of Nuclear Explosives in Cold War America

(2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Project Gasbuggy tests Nuclear “Fracking”.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/project-gasbuggy. Last Updated: December 4, 2024. Original Published Date: December 10, 2013.