by Bruce Wells | Jan 25, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

The Elizabeth Watts shipped hundreds of barrels of petroleum from Philadelphia to London during the Civil War.

The 19th century U.S. petroleum industry launched many new industries for producing, refining, and transporting the highly prized resource. With oil demand rapidly growing worldwide, America exported oil (and kerosene) during the Civil War when a small Union brig sailed across the Atlantic.

Soon after Edwin L. Drake drilled the first American oil well in 1859 along a creek in northwestern Pennsylvania, entrepreneurs swept in and wooden derricks sprang up in Venango and Crawford counties. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 23, 2024 | Petroleum Transportation

Beginning soon after its 1979 opening day, the Iowa 80 Trucking Museum has hosted an annual Jamboree attended by thousands. The museum in Walcott has more than 100 antique trucks on display, including an 1890 Standard Oil triple wagon; a 1903 Eldridge; a 1910 Avery tractor/gasoline farm wagon; and a 1911 Walker Electric Model 43.

The trucking collection off Interstate 80 at the “World’s Largest Truck Stop” began thanks to truck stop founder Bill Moon, who had a passion for trucks and truck history. Every summer, the museum at exit 284 on I -80 outside Walcott, Iowa, hosts a variety of events for truckers and other travelers, teachers, students — and transportation history buffs.

In 2024, the Iowa museum celebrated U.S. trucking history by showcasing its 1924 White Model 40 Wrecker, now on permanent display (and featured in the 1991 film Fried Green Tomatoes). The Model 40’s four-cylinder, 371-cubic-inch engine was produced at the White factory in Cleveland, Ohio, factory.

“If you are the least bit into cars you will find the museum interesting and well worth the stop,” notes a visitor from Legendary Collector Cars. “From what we could tell, it looks like this I-80 Exit at Walcott, Iowa, is about to become the over-the-road truckers Disneyland in a few years.”

“Bill had a passion for collecting antique trucks and other trucking memorabilia,” notes the Iowa 80 Trucking Museum website. “We are pleased to be able to share this collection with the general public. Every truck has a story to tell and can provide a unique glimpse back in time. Many rare and one-of-a-kind trucks are on display.”

The museum, which offers short films about trucking history, attracts all kinds of visitors, from those interested in antique trucks to those wanting to learn the history of modern, big rigs. Exhibit spaces, greatly expanded in 2012, today include free smartphone apps with audio narratives.

Since its inception in 1979, the Truckers Jamboree has been celebrating America’s Truckers. This event is a great place to celebrate and learn about trucking history — and those big rigs.

The descriptions provide additional details about each truck not found on the limited space of exhibit signs. Visitors can scan a “QR” code at the welcome desk to download the app. Upcoming museum visitors can download it from the website. The innovation — increasingly found at museums — allows both virtual and actual visitors to scan and download exhibit information.

Celebrating Trucking History

“The Iowa 80 Trucking Museum’s mission is to celebrate trucking and to preserve and share its history,” noted Marketing Director Heather DeBaillie in 2012. The smartphone apps, give visitors even more information about the exhibits, “and also give those who are unable to visit the museum the opportunity to learn more about trucking history,” she said.

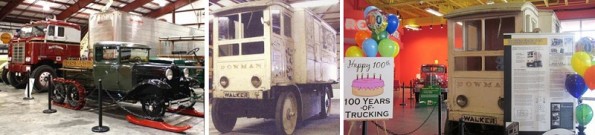

A century of trucking technology is on exhibit at the Iowa 80 Trucking Museum, which on July 15, 2011, celebrated the birthday of its rare 1911 Walker electric truck, which once delivered dairy products.

The annual Jamborees in July host nearly 30,000 drivers and their families from 23 different states and Canada, according to the marketing director. During two days guests enjoyed 175 exhibits — and a Super Truck Beauty Contest with 59 contestants.

In 2011, the trucking museum hosted a birthday party for its Walker electric truck — with the party coinciding with the 32nd annual Walcott Truckers Jamboree at its next-door neighbor, the Iowa 80 Truck Stop, DeBaillie noted.

The antique truck display included more than 200 vehicles. Thousands also enjoyed an Iowa pork chop cookout; a Trucker Olympics; carnival games; a concert and fireworks display.

A 1929 International Harvester. Photo courtesy Legendary Collector Cars, which notes: “If you are the least bit into cars you will find the museum interesting and well worth the stop.”

Trucking Museum 1901 Electric Truck

The Walker truck’s 2011 centennial birthday party at the Iowa 80 Trucking Museum celebrated an electric manufactured by the Walker Vehicle Company of Chicago.

The company produced electric vehicles until late 1941. Walker trucks were used mainly as delivery trucks in major cities — delivering ice cream and other dairy products, baked goods and dry goods.

Although the 1919 International Harvester’s four-cylinder gasoline engine provided a top speed of just 17 mph, it was the first truck to climb Pike’s Peak.

The Iowa 80 Trucking Museum’s 1911 Walker electric truck was owned by Bowman Dairy and used to deliver milk to hospitals, restaurants and hotels, according to curator Dave Meier. It is one of only a handful of Walker Electric trucks known to still exist.

“Many people think that electric vehicles are a recent invention, when in fact they were in production over 100 years ago,” explained Meir.

Electric vehicles were popular in the late 19th century and early 20th century – until advances in internal combustion engine technology and mass production of cheaper gasoline vehicles led to a decline in their use (also see Cantankerous Combustion — 1st U.S. Auto Show).

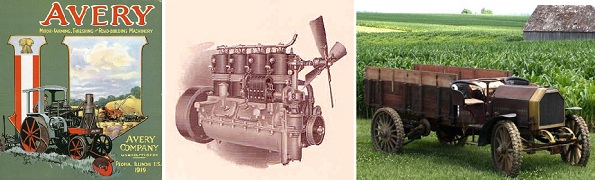

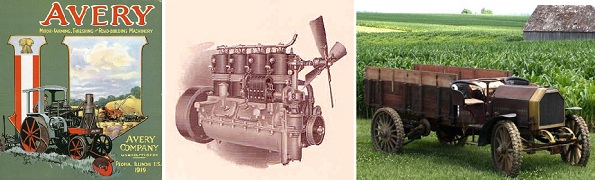

Among the exhibits at the trucking museum is one of the few surviving examples of an Avery gasoline-powered tractor. Avery Company of Peoria, Illinois, began producing coal (and straw)-burning steam tractors in 1891 — and became the world’s largest tractor supplier. It was also one of the first companies to manufacture gasoline tractors.

Manufactured in Peoria, Illinois, Avery tractors brought new efficiency to rural America — and the world. The Iowa 80 Trucking Museum’s 1910 Avery “Tractor-Gasoline Farm Wagon” (at right) was promoted with the slogan, “Makes Power Farming Possible on the Average Sized Farm.”

Created by his family, the Iowa 80 Trucking Museum was a dream of Bill Moon, who founded the Iowa 80 truck stop. Standard Oil originally built the stop in 1964 – when Interstate 80 was still under construction. In September 1965, Moon took over management and purchased it from Amoco in 1984. He managed its growth until his death in 1992.

Plan a visit to the Iowa 80 Trucking Museum.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Iowa 80 Trucking Museum.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: December 28, 2024. Original Published Date: April 18, 2012.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 14, 2024 | Petroleum Transportation

The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History has educated millions of visitors about the history of U.S. transportation since “America on the Move” opened in November 2003 on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Today’s first-floor exhibits in the General Motors Hall of Transportation include the 1903 Winton (the first automobile to drive across the country), bicycles, carriages, antique automobiles, and a 1959 Chicago Transit Authority “L” mass transit car. A 260-ton locomotive built in 1926 is featured near exhibits about the “People’s Highway,” U.S. Route 66.

“America on the Move” also displays a red, 1931 Ford truck representing a typical oilfield service company.

An exhibit about the history of Route 66 — commissioned in 1926 and fully paved by the late 1930s — is part of the Transportation Hall at the National Museum of American History. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The $22 million Transportation Hall encompasses 26,000 square feet and displays more than 340 historic objects. The space features 19 historic settings in chronological order reflecting the nation’s relationship with great and small roadways.

“America on the Move replaces exhibits of road and rail transportation and civil engineering installed when the National Museum of American History opened as the Museum of History and Technology in 1964,” notes the American on the Move website page.

“We would not do an exhibit about cars and trains, or even a transportation history exhibit. It would be an exhibit about transportation in American history,” the site adds.

Visitors to the Hall of Transportation learn how and why the U.S. interstate highway system began in the 1950s. Photo by Bruce Wells.

“America on the Move” features the Smithsonian’s extensive transportation collection using multimedia technology — and a large displays, including PS-4 class steam locomotive (No. 1401) built in 1926. The exhibition educates visitors about the history of U.S. transportation infrastructure, and “reveals America’s fascination with life on the road.” (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Nov 3, 2024 | Petroleum Transportation

President Woodrow Wilson in 1914 opened a maritime project to support petrochemicals.

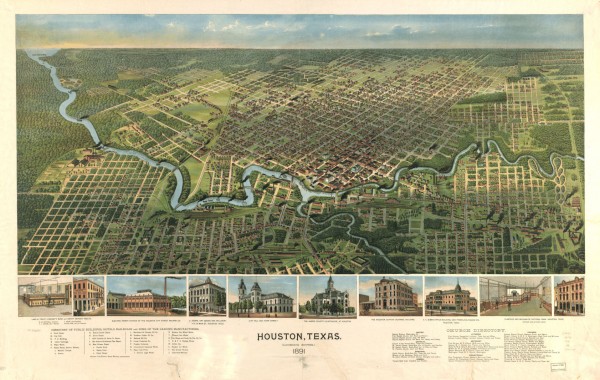

The Houston Ship Channel, the “port that built a city,” opened for ocean-going vessels on November 10, 1914, making Texas home to a world-class commercial port. President Woodrow Wilson saluted the occasion from his desk in the White House by pushing an ivory button wired to a cannon in Houston.

A 1950 postcard of the Houston Ship Channel, which officially opened on November 10, 1914, as an ocean-vessel waterway linking Houston, the San Jacinto River, Galveston Bay, and the Gulf of Mexico.

The National Anthem played from a barge in the center of the Turning Basin as Sue Campbell, daughter of Houston Mayor Ben Campbell, sprinkled white roses into the water, according to a Port of Houston historian.

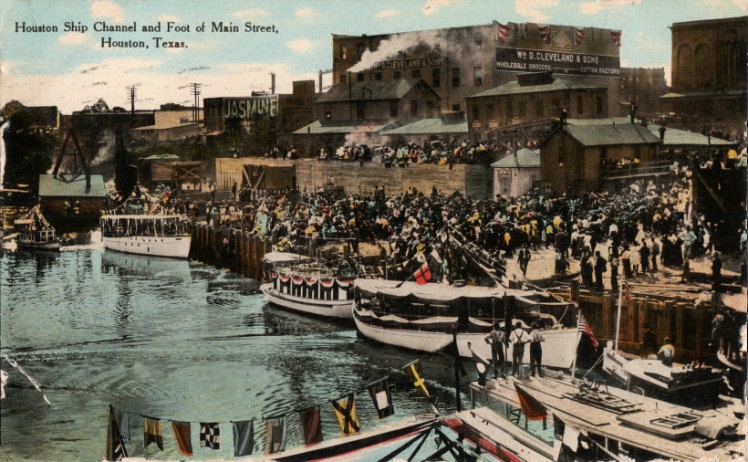

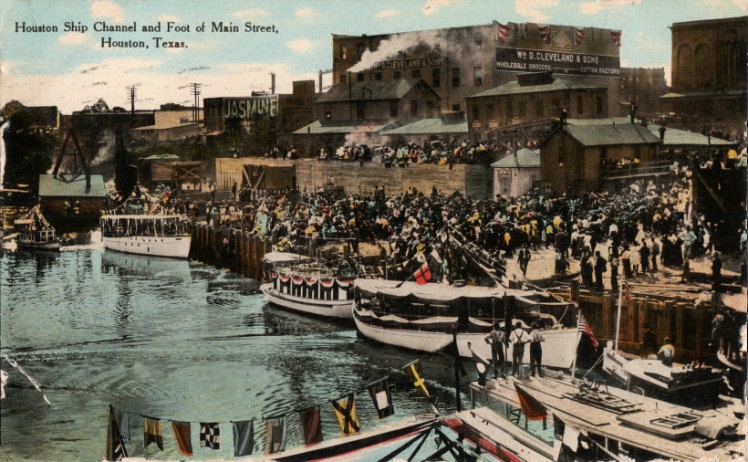

An image from a 1915 postcard of the Houston Ship Channel. One year earlier, President Woodrow Wilson officially opened the newly dredged waterway. Photo courtesy Fort Bend Museum, Richmond, Texas.

“I christen thee Port of Houston; hither the boats of all nations may come and receive a hearty welcome,” Campbell proclaimed.

The bayou had been used to ship goods to the Gulf of Mexico as early as the 1830s. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) described the original waterway — known as Buffalo Bayou — as “swampy, marshy and overgrown with dense vegetation.”

“Steamboats and shallow-draft vessels were the only boats able to navigate the complicated channel, noted ASCE, adding that in 1909, Harris County citizens formed a navigation district (an autonomous governmental body for supervising the port) and issued bonds to fund half the cost of dredging the channel.

The Houston Ship Channel on Buffalo Bayou leads upstream to Houston – where downtown can be seen at top right. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Digital Visual Library.

According to the Port of Houston Authority of Harris County, in 1937 the steamship Laura traveled from Galveston Bay up Buffalo Bayou to what is now Houston.

The steamship’s trip, in water no deeper than six feet, proved the bayou was navigable by sizable vessels and established a commercial link between Houston and ports around the world

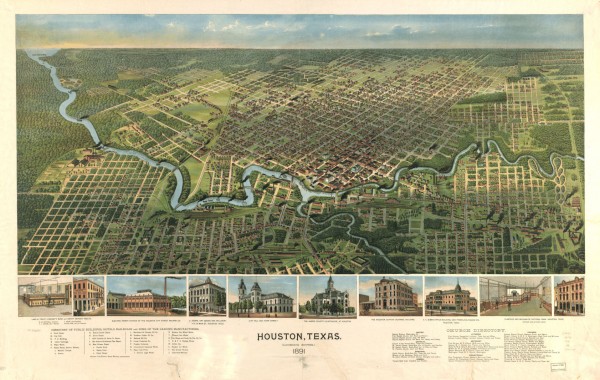

A “Bird’s Eye” view of Houston in 1891. Today’s Port of Houston is ranked first in foreign cargo and among the largest ports in the world. Map image courtesy Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

“With the discovery of oil at Spindletop in 1901 and crops such as rice beginning to rival the dominant export crop of cotton, Houston’s ship channel needed the capacity to handle newer and larger vessels,” reported the Port Authority, administrator of the channel.

Harris County voters in January 1910 overwhelmingly approved dredging their ship channel to a depth of 25 feet for $1.25 million. The U.S. Congress provided matching funds. As work began in 1912, similar giant maritime projects included construction of the Panama Canal and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway.

An oil museum in Beaumont, Texas, includes petroleum science and refinery exhibits for educating young people about the Port of Houston. Photo courtesy The Texas Energy Museum.

By 1930, eight refineries were operating along the deep water channel, ASCE notes. The area eventually supported massive petrochemical complexes along the shoreline of processing facilities and oil refineries, including ExxonMobil’s Baytown Refinery.

A circa 1910 postcard of the Houston Ship Channel and foot of Main Street, Houston, Texas, S. H. Kress & Co., courtesy University of Houston Digital Library.

Under continuous development since its original construction, the Houston Ship Channel has been extended to reach 52 miles with a depth of 45 feet and a width of up to 530 feet. It travels from the Gulf through Galveston Bay and up the San Jacinto River, ending four miles east of downtown Houston.

Although the dredging vessel Texas first signaled by whistle the channel’s completion on September 7, 1914, the official opening date has remained when Sue Campbell sprinkled her white roses and President Wilson remotely fired his cannon.

With refineries and expanded liquified terminals for exporting natural gas (LNG), the Texas waterway has grown into one of the largest petrochemical facilities in the world.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Sheer Will: The Story of the Port of Houston and the Houston Ship Channel  (2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 – Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title – “Houston Ship Channel of 1914.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/houston-ship-channel. Last Updated: November 18 2024. Original Published Date: November 25, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 24, 2024 | Petroleum Transportation

Early autos shared unpaved roads with horses and wagons.

The first U.S. Auto show opened in New York City’s Madison Square Garden in 1900, just five years after Charles Duryea claimed the first American patent for a gasoline-powered automobile. Gas proved to be the least popular source of engine power.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Sep 20, 2024 | Petroleum Transportation

Chicago Bridge & Iron Company in 1923 began erecting giant, spherical pressure vessels.

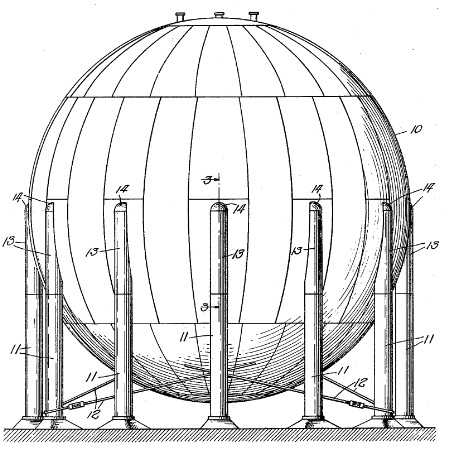

Seen from the highway, the spheres look like massive eggs or fanciful Disney architectural projects. A 19th-century iron bridge manufacturer from Chicago conceived the idea for these globes — at first made by riveting together wrought iron plates. Modern highly pressured vessels are vital for storing and transporting liquified natural gas (LNG).

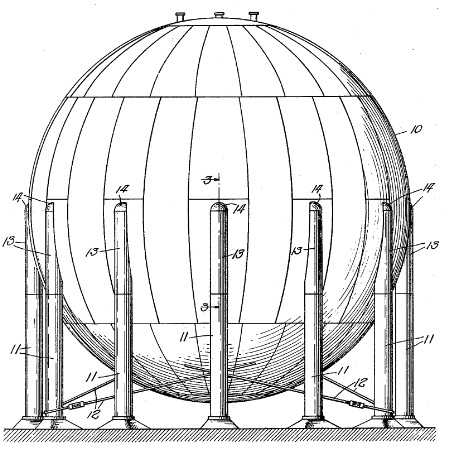

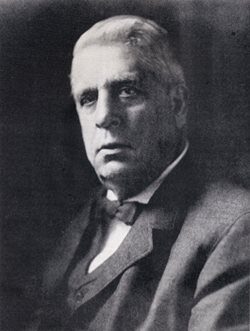

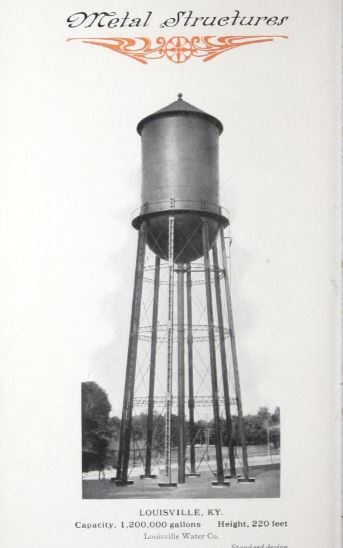

Chicago Bridge & Iron Company (CB&I) officially named “Hortonspheres” — also called Horton spheres — after Horace Ebenezer Horton (1843-1912), the company founder and designer of water towers and rounded storage vessels. His son George would patent designs standing among the great innovations to come to the oil patch.

Hortonspheres, the trademarked name of massive containers for storing and transporting liquified natural gas (LNG), were invented by a bridge-building company.

Horace Horton grew up in Chicago, where he became skilled in mechanical engineering. He was 46 years old when he formed CB&I in 1889. His company prospered, building seven bridges across the Mississippi River.

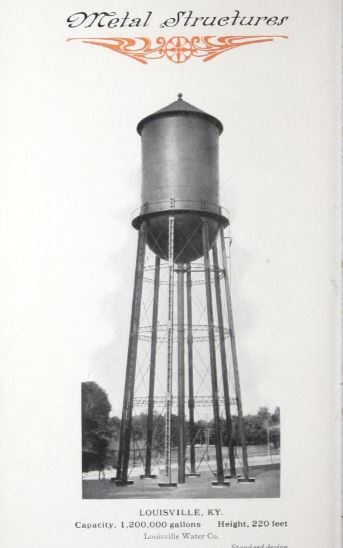

Horton then expanded the company’s Washington Heights, Illinois, fabrication plant to begin manufacturing water tanks. It was a decision that would bring water towers to hundreds of towns.

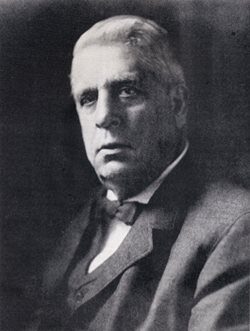

Horace Ebenezer Horton (1843-1912) founded the company that would build the world’s first “field-erected spherical pressure vessel.”

CB&I erected its first elevated water tank in Fort Dodge, Iowa, in 1892, according to the company, which has noted that “the elevated steel plate tank was the first built with a full hemispherical bottom, one of the company’s first technical innovations.”

When Horton died in 1912, his company was just getting started. Soon, the company’s elevated towers were providing efficient water storage and pipeline pressure that benefited many cities and towns. CB&I’s first elevated “Watersphere” tank was completed in 1939 in Longmont, Colorado.

Improved Oilfield Structures

The company brought its steel plate engineering expertise to the oil and natural gas industry as early as 1919, when it built a petroleum tank farm in Glenrock, Wyoming, for Sinclair Refining Company (formed by Harry Sinclair in 1916).

Horace E. Horton’s company designed spherical storage vessels for his Chicago Bridge & Iron Company. Photo courtesy CB&I.

CB&I’s innovative steel plate structures and construction technologies proved a great success. The company left bridge building entirely to supply the petroleum infrastructure market.

A spherically bottomed water tower shown in the Chicago Bridge & Iron Company 1912 sales book.

Newly discovered oilfields in Ranger, Texas, in 1917 and Seminole, Oklahoma, in the 1920s were straining the nation’s petroleum storage capacity. A lack of pipelines and storage facilities in booming West Texas was a big problem.

In the Permian Basin, an exploration company’s executives were desperate to store soaring oil production. They hired engineers to design an experimental tank capable of holding up to five million barrels of oil at Monahans, Texas. Construction in early 1928 took three months working 24 hours a day.

Roxana Petroleum Company’s massive storage structure used concrete-coated earthen walls 30 feet tall. The oil reservoir was covered with a cedar roof to slow evaporation.

But when no solution could be found for leaking seams, the oil storage attempt was abandoned.The concrete oval, which briefly became a water park in 1958, later became home to Monahans’ Million Barrel Museum.

By 1923, CB&I’s storage innovations like its “floating roof” oil tank had greatly increased safety and profitability as well as setting industry standards. That year the company built its first Hortonsphere in Port Arthur, Texas.

Liquefied Natural Gas

Soon, spherical vessels of all sizes were being used for storage of compressed gases such as propane and butane. Hortonspheres also hold liquefied natural gas (LNG) produced by cooling natural gas at atmospheric pressure to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point it liquefies.

As an iconic engineering example of form following function, the sphere is the ideal shape for a vessel that resists internal pressure.

In the first Port Arthur installation and up until about 1941, the component steel plates were riveted; thereafter, welding allowed for increased pressures and vessel sizes. As metallurgy and welding advances brought tremendous gains in Hortonspheres’ holding capacities, they also have proven to be an essential part of the modern petroleum refining business.

CB&I constructed fractionating towers for many petroleum refineries, beginning with Standard Oil of Louisiana at Baton Rouge in 1930. The company also built a giant, all-welded 80,000-barrel oil storage tank in New Jersey.

Since its first sphere in 1923, Chicago Bridge & Iron by 2013 fabricated more than 3,500 Hortonspheres for worldwide markets in capacities reaching more than three million gallons — reportedly the world’s top spherical storage container builder.

Poughkeepsie Hortonsphere

Fascinated by geodesic domes and similar structures, Jeff Buster discovered a vintage Hortonsphere in Poughkeepsie, New York. In 2012 he contacted the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation.

A Hortonsphere viewed in 2012 from the “Walkway over the Hudson” in Poughkeepsie, New York. It was dismantled in 2013. Photo courtesy Jeff Buster.

Buster wanted the agency to save Horton’s sphere at the corner of Dutchess and North Water streets. He asked that an effort be made “to preserve this beautiful and unique ‘form following function’ structure, which is in immediate risk of being demolished.”

Buster posted a photo of the Poughkeepsie Hortonsphere on a website devoted to geodesic domes. “The jigsaw pattern of steel plates assembled into this sphere is unique,” he wrote.

“The layout pattern is repeated four times around the vertical axis of the tank,” Buster added. “With the rivets detailing the seams, the sphere is extremely cool and organic feeling.”

Although the steel tank, owned by Central Hudson Gas and Electric Company, was demolished in late 2013, Buster’s photo has helped preserve its oil patch legacy.

Liquified Natural Gas at Sea

Sphere technology became seaborn as well. On February 20, 1959, after a three-week voyage from Lake Charles, Louisiana, the Methane Pioneer — the world’s first LNG tanker — arrived at the world’s first LNG terminal at Canvey Island, England.

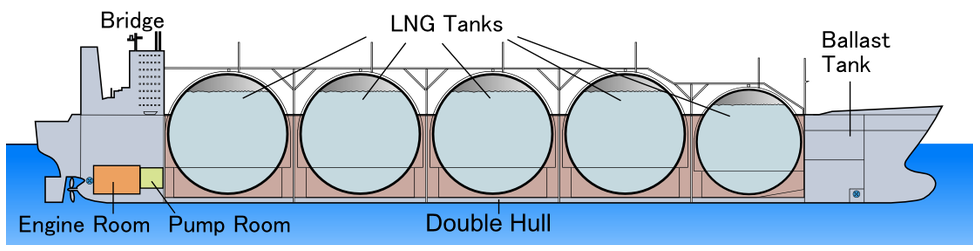

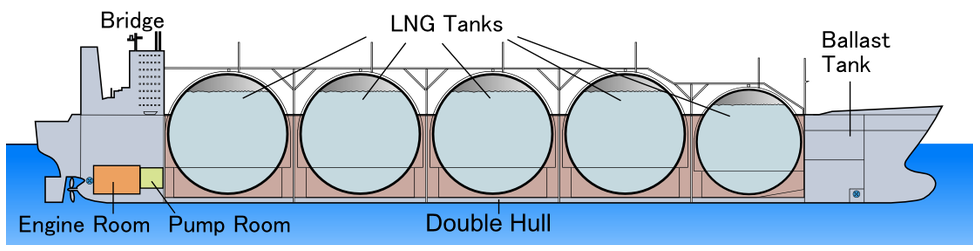

Ships began transporting liquified natural gas as early as 1959. Modern LNG tankers are many times larger and protected with double hulls.

The Methane Pioneer, a converted World War II liberty freighter, contained five, 7,000-barrel aluminum tanks supported by balsa wood and insulated with plywood and urethane. The 1959 successful voyage across the Atlantic demonstrated that large quantities of liquefied natural gas could be transported safely across the ocean.

Most modern LNG carriers have between four and six tanks on the vessel. New classes have a cargo capacity of between 7.4 million cubic feet and 9.4 million cubic feet. Each ship is equipped with its own re-liquefaction plant.

In 2015 — about 100 years after Horace Ebenezer Horton died — Mitsubishi Heavy Industries announced constructing of the next-generation LNG carriers to transport the shale gas produced in North America. Rapid growth of U.S. natural gas production came from hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) of shale formations in North Dakota and other states.

In 2023, there were 772 LNG storage vessels worldwide, according to Statista.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Sheer Will: The Story of the Port of Houston and the Houston Ship Channel  (2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2014). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Horace Horton’s Spheres.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/hortonspheres/. Last Updated: September 17, 2024. Original Published Date: December 14, 2016.