by Bruce Wells | Sep 19, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

Chicago Bridge & Iron Company in 1923 began erecting giant, spherical pressure vessels.

Seen from the highway, the spheres look like massive eggs or fanciful Disney architectural projects. A 19th-century iron bridge manufacturer from Chicago conceived the idea for these globes — at first made by riveting together wrought iron plates. Modern highly pressured vessels are vital for storing and transporting liquified natural gas (LNG).

Chicago Bridge & Iron Company (CB&I) officially named “Hortonspheres” — also called Horton spheres — after Horace Ebenezer Horton (1843-1912), the company founder and designer of water towers and rounded storage vessels. His son George would patent designs that stand among the great innovations to come to the oil patch. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Aug 5, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

Bertha Benz’s 65-mile drive in 1888 made headlines for her husband’s fledgling auto company.

German mechanical engineer Karl Friedrich Benz invented and built a three-wheel “motorwagen,” today recognized as the world’s first car. His wife helped steer the company’s first marketing campaign.

Although others had experimented with electric and steam-powered vehicles — and a gasoline-powered engine had been added to a pushcart in 1870 — mechanical engineer (and locksmith) Karl Benz invented the modern car in 1885 when he built his “Fahrzeug mit Gasmotorenbetrieb” (vehicle with gas engine) in Mannheim, Germany. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jun 10, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

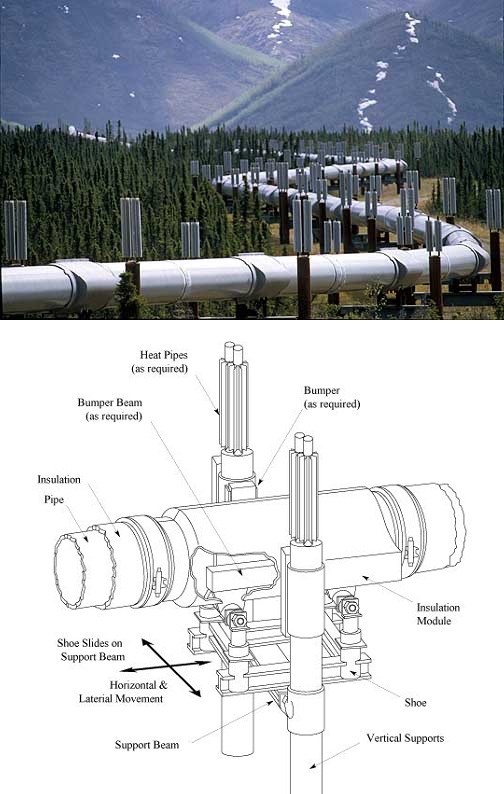

North Slope oil began moving through Alaska’s 800-mile pipeline system in 1977.

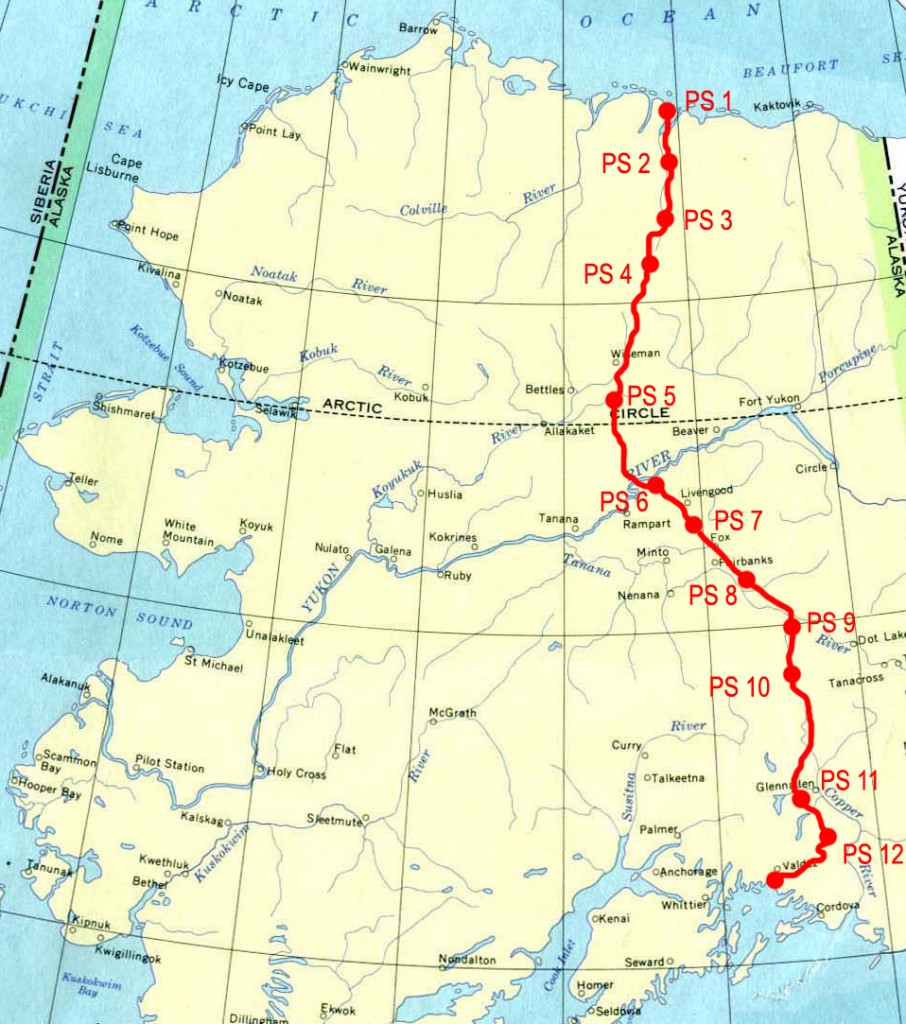

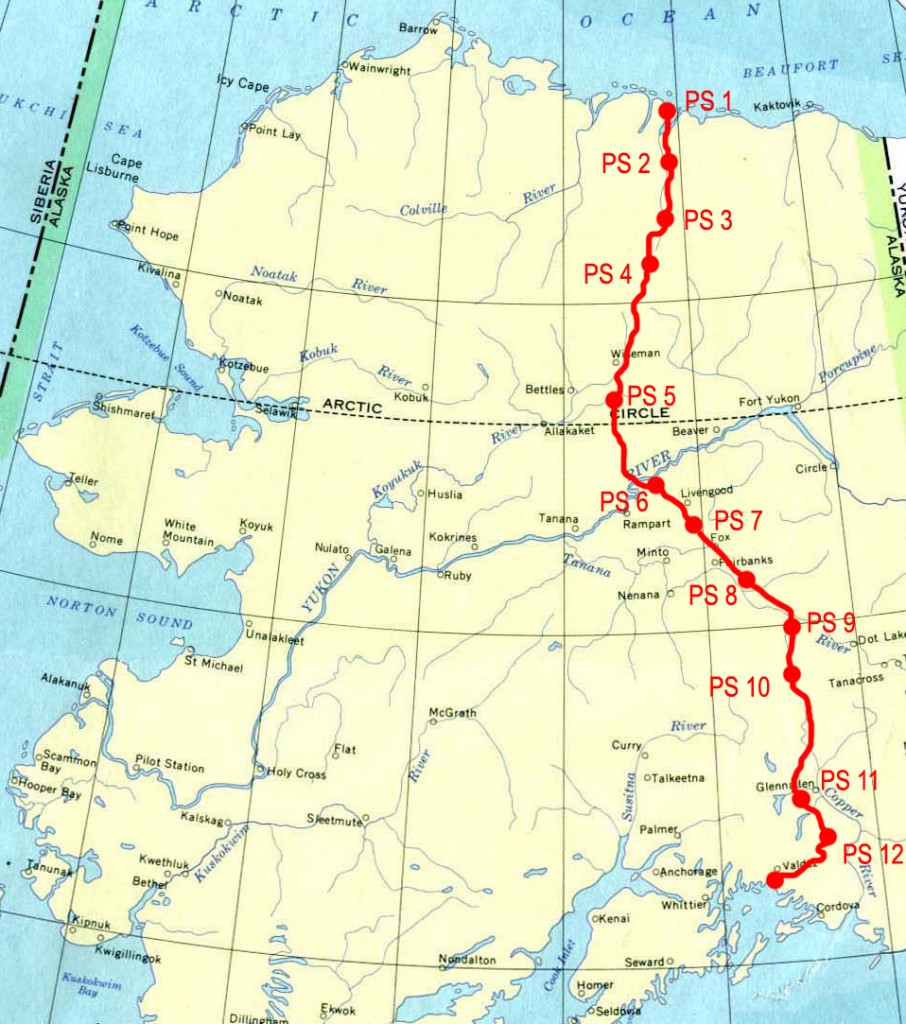

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, designed and constructed to carry billions of barrels of North Slope oil to the port of Valdez, has been recognized as a landmark of engineering. On June 20, 1977, the 800-mile pipeline began carrying oil from Prudhoe Bay oilfields to the Port of Valdez at Prince William Sound. The oil began arriving 38 days later.

In July 1973, a tie-breaking vote by Vice President Spiro Agnew in the U.S. Senate passed the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act after years of debate about the pipeline’s environmental impact. Concerns included spills, earthquakes, and elk migrations.

The Alaskan Pipeline system’s 420-miles above ground segments use a zig-zag configuration to allow for expansion or contraction of the pipe.

With the laying of the first section of pipe on March 27, 1975, construction began on what at the time was the largest private construction project in American history.

The 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline system, including pumping stations, connecting pipelines, and the ice-free Valdez Marine Terminal, ended up costing billions. The last pipeline weld occurred on May 31, 1977, and oil from the Prudhoe Bay field began flowing to the port of Valdez on June 20, traveling at four miles an hour through the 48-inch-wide pipe.

The pipeline system cost $8 billion, including terminal and pump stations, and would transport about 20 percent of U.S. petroleum production. Tax revenue earned Alaskans about $50 billion by 2002.

Engineering Milestones

Special engineering was required to protect the environment in difficult construction conditions, according to Alyeska Pipeline Service Company. Details about the pipeline’s history include:

- Oil was first discovered in Prudhoe Bay on the North Slope in 1968.

- Alyeska Pipeline Service Company was established in 1970 to design, construct, operate and maintain the pipeline.

- The state of Alaska entered into a right-of-way agreement on May 3, 1974; the lease was renewed in November of 2002.

- Thickness of the pipeline wall: .462 inches (466 miles) & .562 inches (334 miles).

- The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System crosses the ranges of the Central Arctic heard on the North Slope and the Nelchina Herd in the Copper River Basin.

- The Valdez Terminal covers 1,000 acres and has facilities for crude oil metering, storage, transfer and loading.

- The pipeline project involved some 70,000 workers from 1969 through 1977.

- The first pipe of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System was laid on March 27, 1975. Last weld was completed May 31, 1977.

The Alaskan pipeline brings North Slope production to tankers at the port of Valdez. Map courtesy USGS.

- The pipeline is often referred to as “TAPS” – an acronym for the Trans Alaska Pipeline System.

- More than 170 bird species have been identified along the pipeline.

- First oil moved through the pipeline on June 20, 1977; it took 28 days to arrive at Valdez.

The pipeline delivered oil almost a decade after the Prudhoe Bay oilfield’s discovery. “OMAR” was the Organization for Management of Alaska’s Resources, now the Resource Development Council for Alaska.

- 71 gate valves can block the flow of oil in either direction on the pipeline.

- First tanker to carry crude oil from Valdez: ARCO Juneau, August 1, 1977.

- Maximum daily throughput was 2,145,297 on January 14, 1988.

- The pipeline is inspected and regulated by the State Pipeline Coordinator’s Office.

At the peak of its construction in the fall of 1975, more than 28,000 people worked on the pipeline. There were 31 construction camps built along the route, each built on gravel to insulate and help prevent pollution to the underlying permafrost.

Heaters

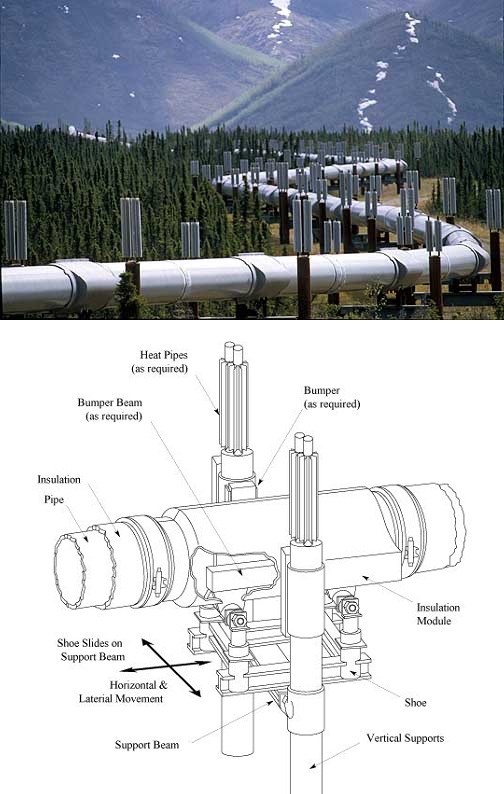

The above-ground sections of the pipeline (420 miles) were constructed in a zigzag configuration to allow for expansion or contraction of the pipe because of temperature changes.

Specially designed anchor structures, 700 feet to 1,800 feet apart, securely hold the pipe in position. In warm permafrost and other areas where heat might cause undesirable thawing, the supports contain two, two-inch pipes called “heat pipes.”

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline today has been recognized as a landmark engineering feat. It remains essential to Alaska’s economy.

The first tanker carrying North Slope oil from the new pipeline sailed out of the Valdez Marine Terminal on August 1, 1977. By 2010, the pipeline had carried about 16 billion barrels of oil. Alaska’s total oil production in 2013 was nearly 188 million barrels, or about seven percent of total U.S. production.

The first Alaska oil well with commercial production was completed in 1902 in a region where oil seeps had been known for years. The Alaska Steam Coal & Petroleum Syndicate produced the oil near the remote settlement of Katalla on Alaska’s southern coastline. The oilfield there also led to construction of Alaska Territory’s first refinery.

The modern Alaskan petroleum industry began in 1957 with an oilfield discovery at Swanson River. The next major milestone came when Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) and Exxon discovered the Prudhoe Bay field in March 1968 about 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

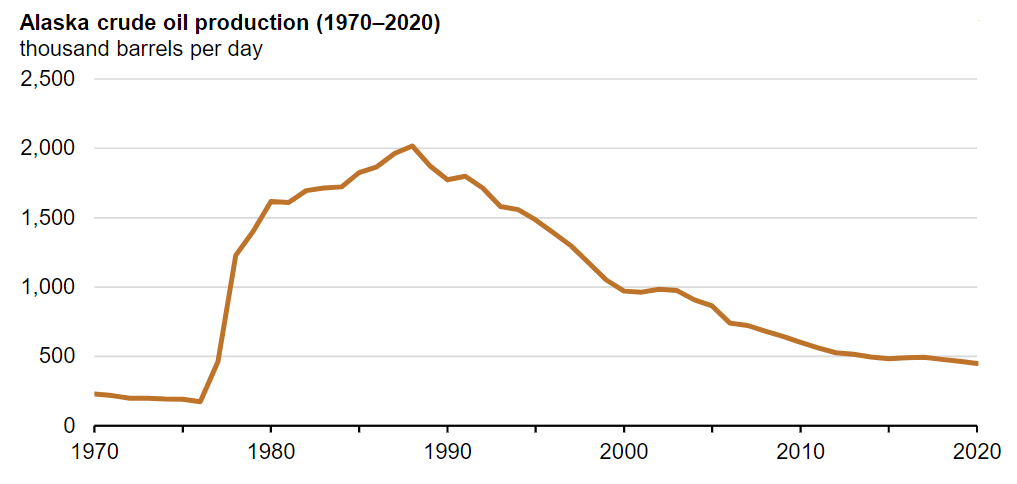

Rise and Fall of Production

The Prudhoe Bay oilfield proved to be the largest in North America at more than 213,500 acres — exceeding the “Black Giant” East Texas Oilfield discovered in 1930.

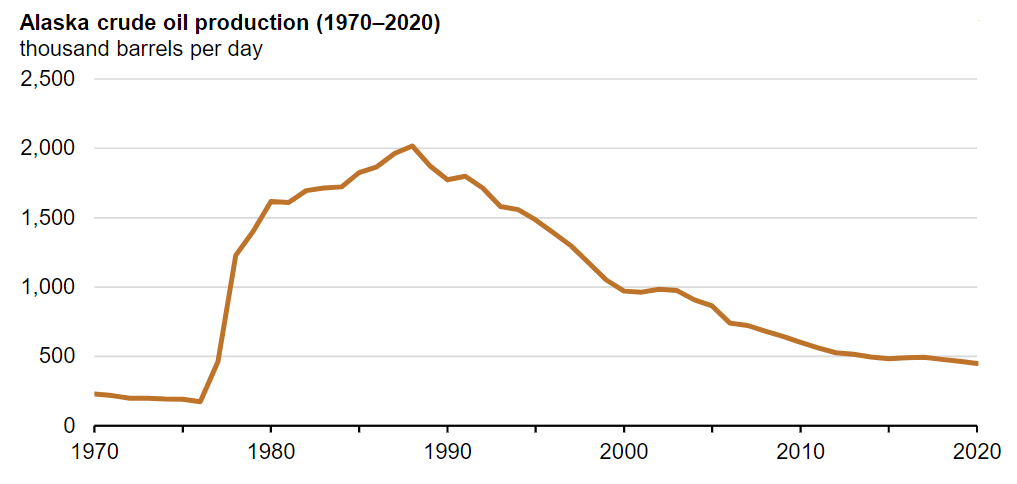

Alaska’s daily oil production peaked in 1988 at about 2 million barrels of oil per day, according to the Department of Energy Energy Information Administration (EIA), Petroleum Supply Monthly.

Annual Alaska oil production peaked in 1988 at 738 million barrels of oil — about 25 percent of U.S. oil production at the time, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). Production averaged about 448,000 barrels of oil per day in 2020, the lowest level in more than 40 years.

“Crude oil production in Alaska averaged 448,000 barrels per day (b/d) in 2020, the lowest level of production since 1976,” the agency noted in its April 2021 Today in Energy report. “Last year’s production was over 75 percent less than the state’s peak production of more than 2 million b/d in 1988.”

The decline in the state’s oil production has decreased deliveries in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, EIA added. Lower oil volumes caused oil to move more slowly in the pipeline, and the travel time from the North Shore to Valdez increased by 18 days in 2020.

For America’s pipeline history during World War II, see Big Inch Pipelines of WW II and PLUTO, Secret Pipelines of WWII.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Great Alaska Pipeline (1988); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier

(1988); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier (1997); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals

(1997); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals (1993); Oil: From Prospect to Pipeline

(1993); Oil: From Prospect to Pipeline (1971). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1971). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Trans-Alaska Pipeline History.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/trans-alaska-pipeline. Last Updated: July 14, 2025. Original Published Date: June 20, 2015.