by Bruce Wells | Jun 15, 2023 | Petroleum Technology

Armais Arutunoff designed an efficient down-hole centrifugal pump and founded oilfield service company.

The modern petroleum industry owes a lot to Armais Sergeevich Arutunoff, the son of an Armenian soap maker.

With the help of a prominent Oklahoma oil company president, Arutunoff designed and built the first practical electric submersible pump (ESP). His revolutionary concept would enhanced oilfield production in wells worldwide.

A 1936 Tulsa World article described the Arutunoff downhole pump as “an electric motor with the proportions of a slim fence post which stands on its head at the bottom of a well and kicks oil to the surface with its feet.”

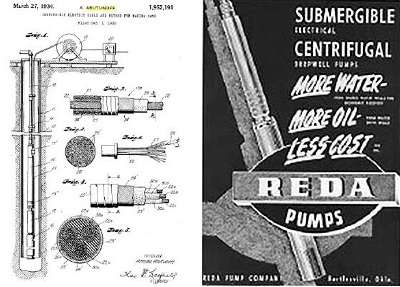

Armais Arutunoff will obtain 90 patents. Above, a 1934, patent for an improved well pump and electric cable. At right, a 1951 “submergible” Reda Pump advertisement.

By 1938, an estimated two percent of all the oil produced in the United States with artificial lift, was lifted by an Arutunoff pump.

According to an October 2014 article in the Journal of Petroleum Technology, the first patent for an oil-related electric pump was issued in 1894 to Harry Pickett. His invention used a downhole rotary electric motor with “a Yankee screwdriver device to drive a plunger pump.”

Armais Arutunoff (1893-1978), inventor of the modern electric submersible pump.

More than two decades later, Robert Newcomb received a 1918 patent for his “electro-magnetic engine” driving a reciprocating plunger pump.

“Heretofore, in very deep wells the rod that is connected to the piston, and generally known as the ‘sucker’ rod, very often breaks on account of its great length and strains imposed thereon in operating the piston,” noted Newcomb in his patent application.

Although several patents followed those of Picket and Newcomb, the Journal reports, “it was not until 1926 that the first patent for a commercial, operatable ESP was issued – to ESP pioneer Armais Arutunoff. The cable used to supply power to the bottomhole unit was also invented by Arutunoff.”

Russian Electrical Dynamo of Arutunoff (Reda)

Arutunoff built his first ESP in 1916 in Germany, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. “Suspended by steel cables, it was dropped down the well casing into oil or water and turned on, creating a suction that would lift the liquid to the surface formation through pipes,” reported OHS historian Dianna Everett.

After immigrating to the United States in 1923, in California Arutunoff could not find financial support for manufacturing his pump design. He moved to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1928 at the urging of a new friend – Frank Phillips, head of Phillips Petroleum Company.

“With Phillips’s backing, he refined his pump for use in oil wells and first successfully demonstrated it in a well in Kansas,” noted Everett. The device was manufactured by a small company that soon became Reda Pump.

The name Reda – Russian Electrical Dynamo of Arutunoff – was the cable address of the company that Arutunoff originally started in Germany. The inventor would move his family into a Bartlesville home just across the street from Frank Phillips’ mansion.

The founder of Reda Pump once lived in this Bartlesville, Oklahoma, home across from Frank Phillips, whose home today is a museum. Photo courtesy Kathryn Mann, Only in Bartlesville.

A holder of more than 90 patents in the United States, Arutunoff was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1974. “Try as I may, I cannot perform services of such value to repay this wonderful country for granting me sanctuary and the blessings of freedom and citizenship,” Arutunoff said at the time.

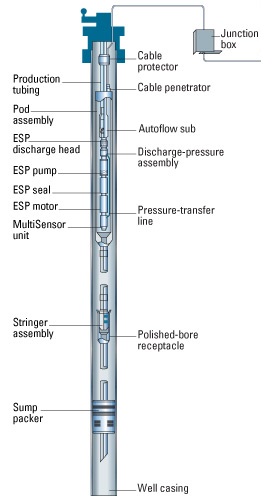

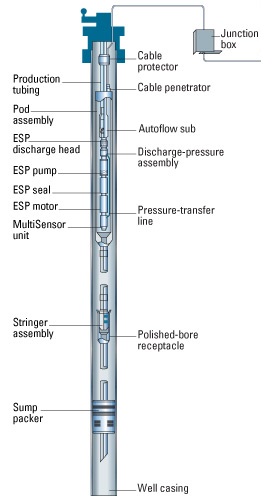

A modern ESP applies artificial lift by spinning the impellers on the pump shaft, putting pressure on the surrounding fluids and forcing them to the surface. It can lift more than 25,000 barrels of fluids per day. Courtesy Schlumberger.

Arutunoff died in February 1978 in Bartlesville. At the end of the twentieth century, Reda was the world’s largest manufacturer of ESP systems. It is now part of Schlumberger.

Son of a Soap Maker

Armais Sergeevich Arutunoff was born to Armenian parents in Tiflis, part of the Russian Empire, on June 21, 1893. His home town, in the Caucasus Mountains between the Caspian and Black Sea, dated back to the 5th Century.

According to an online electrical submersible pump history at ESP Pump, his father was a soap manufacturer and his grandfather a fur trader. In his youth, Arutunoff lived in Erivan (now Yerevan) the capital of Armenia.

The ESP Pump website, which includes a profile of his extensive scientific career, described how Arutunoff’s research convinced him that electrical transmission of power could be efficiently applied to oil drilling and improve the antiquated methods he saw in use in the early 1900s in Russia.

“To do this, a small, yet high horsepower electric motor was needed,” ESP Pump explained. “The limitation imposed by available casing sizes made it necessary that the motor be relatively small.”

However, a motor of small diameter would necessarily be too low in horsepower. “Such a motor would be inadequate for the job he had in mind so he studied the fundamental laws of electricity to find the basis for the answer to the question of how to build a higher horsepower motor exceedingly small in diameter,” according to ESP Power.

By 1916, Arutunoff was designing a centrifugal pump to be coupled to the motor for de-watering mines and ships. To develop enough power it was necessary the motor run at very high speeds. He successfully designed a centrifugal pump, small in diameter and with stages to achieve high discharge pressure.

“In his design, the motor was ingeniously installed below the pump to cool the motor with flow moving up the oil well casing, and the entire unit was suspended in the well on the discharge pipe,” ESP Pump noted. “The motor, sealed from the well fluid, operated at high speed in an oil bath.”

An Upside Down Well Motor

Although Arutunoff built the first centrifugal pump while living in Germany, he built the first submersible pump and motor in the United States while living in Los Angeles.

“Before coming to the U.S. he had formed a small company of his own, called Reda, to manufacture his idea for electric submersible motors,” noted ESP Pump. “He later settled in Germany and then came with his wife and one-year-old daughter to the United States to settle in Michigan, then Los Angeles.”

However, after emigrating to America in 1923, Arutunoff could not find financial support for his down-hole production technology. Everyone he approached turned him down, saying the unit was “impossible under the laws of electronics.”

No one would consider his inventions until a friend at Phillips Petroleum Company — Frank Phillips — encouraged him to form his own company in in Bartlesville. He moved into a house down the street of the

Arutunoff’s manufacturing plant in Bartlesville spread over nine acres, employing hundreds during the Great Depression.

In 1928 Arutunoff moved to Bartlesville, where formed Bart Manufacturing Company, which changed its same to the Reda Pump Company in 1930. He soon demonstrated a working model of an oilfield electric submersible pump.

One of his pump-and-motor devices was installed in an oil well in the El Dorado field near Burns, Kansas – the first equipment of its kinds to be used in a well. One reporter telegraphed his editor, “Please rush good pictures showing oil well motors that are upside down.”

By end of the 1930s Arutunoff’s company held dozens of patents for industrial equipment, leading to decades of success and even more patents. His “Electrodrill” aided scientists in penetrating the Antarctic ice cap for the first time in 1967.

“Arutunoff’s ESP oilfield technology quickly had a significant impact on the oil business,” concluded the ESP Pump article. “His pump was crucial to the successful production over the years of hundreds of thousands of oil wells.”

Also see All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology and Conoco & Phillips Petroleum Museums.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems (1984); Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum

(1984); Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum (2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Inventing the Electric Submersible Pump.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/electric-submersible-pump-inventor. Last Updated: June 16, 2023. Original Published Date: April 29, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 8, 2023 | Petroleum Technology

Established in 1932, the Lane-Wells oilfield service company created powerful perforating guns.

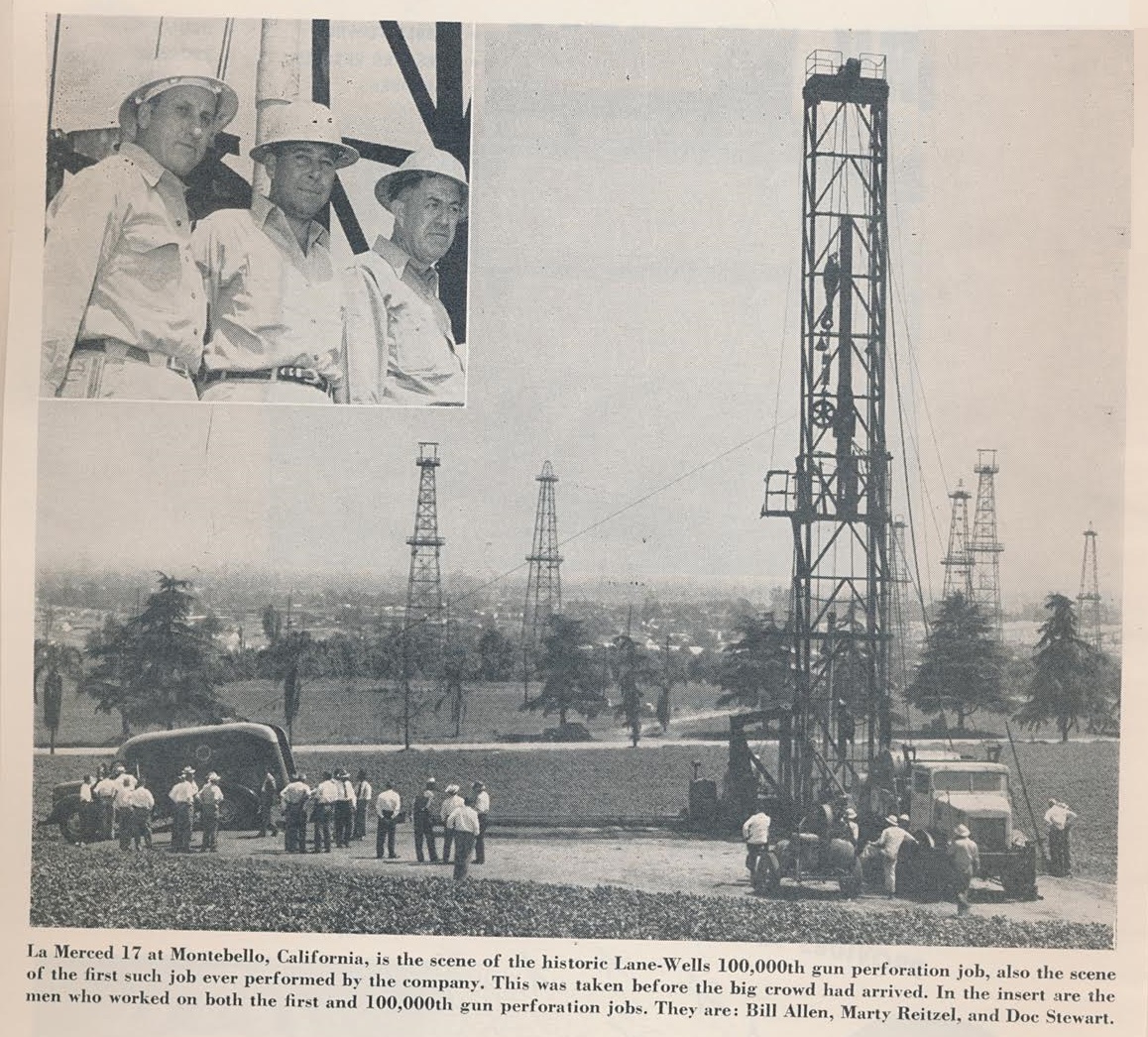

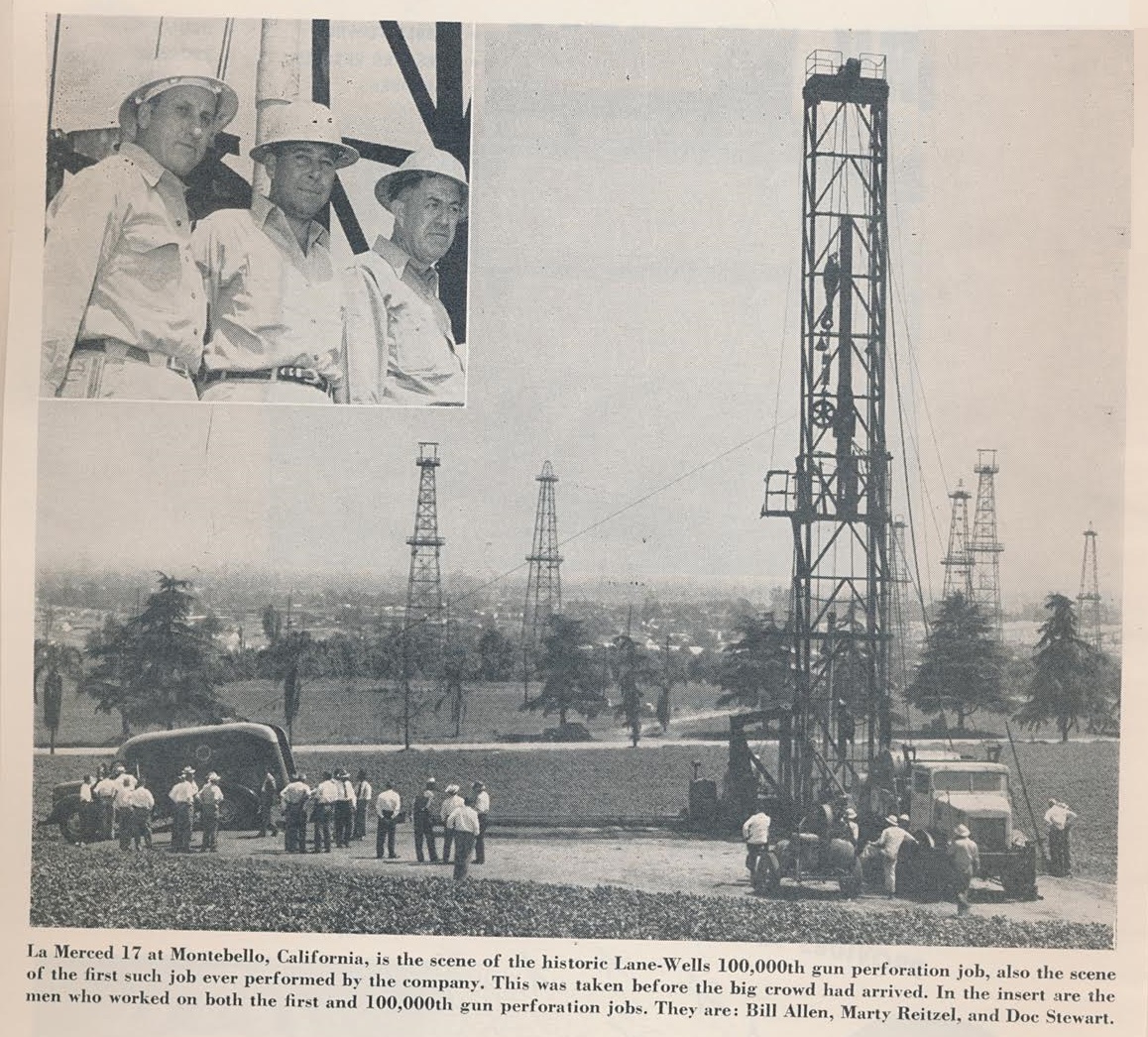

Fifteen years after its first oil well perforation job, Lane-Wells Company returned to the same well near Montebello, California, to perform its 100,000th perforation. The publicity event of June 18, 1948, was a return to Union Oil Company’s La Merced No. 17 well.

The gathering of executives at the historic well celebrated a significant leap in petroleum production technology. The combined inventiveness of the two oilfield service companies had accomplished much in a short time, “so it was a colorful ceremony,” reported a trade magazine.

Officials from both companies and invited guests gathered to witness the repeat performance of the company’s early perforating technology, noted Petroleum Engineer in its July 1948 issue. Among them were “several well-known oilmen who had also been present on the first occasion.”

As production technologies evolved after World War II, Lane-Wells developed a downhole gun with the explosive energy to cut through casing. Above, one of the articles preserved in a family scrapbook, courtesy Connie Jones Pillsbury, Atascadero, California.

Walter Wells, chairman of the board for Lane-Wells, was present for both events. The article reported he was more anxious at the first, which had been an experiment to test his company’s new perforating gun. In 1930, Wells and another enterprising oilfield tool salesman, Bill Lane, came up with a practical way of using guns downhole.

The two men envisioned a tool which would shoot steel bullets through casing and into the formation. They would create a multiple-shot perforator that fired bullets individually by electrical detonation. After many test firings, commercial success came at the Union Oil Company La Merced well.

By late 1935, Lane-Wells had established a fleet of trucks as the company grew into a provider of well-perforations — a key oilfield service for enhancing production (see Downhole Bazooka).

“Bill Lane and Walt Wells worked long hours at a time, establishing their perforating gun business,” explained Susan Wells in a 2007 book. The men designed tools that would better help the oil industry during the Great Depression, she noted. “It was a period of high drilling costs, and the demand for oil was on the rise. Making this scenario worse was the fact that the cost of oil was relatively low.”

What was needed was a high-powered gun for breaking through casing, cement and into formations. An oilfield worker, Sidney Mims, had patented a similar technical tool for this purpose, but could not get it to work as well as it could. Lane and Wells purchased the patent and refined the gun.

Lane-Wells became Baker Atlas, which celebrated its 75 anniversary in 2007, and today is a division of Baker-Hughes

Established in Los Angeles in 1932, the oilfield service company developed a remotely controlled 128-shot gun perforator. “Lane and Wells publicly used the reengineered shotgun perforator they bought from Mims on Union Oil’s oil well La Merced No. 17,” Susan Wells noted in her 2007 book celebrating the 75th anniversary of Baker-Atlas.

“There wasn’t any production from this oil well until the shotgun perforator was used, but when used, the well produced more oil than ever before,” she explained.

Lane-Wells provided perforating services using downhole “bullet guns,” seen here in 1940.

The successful application attracted many other oil companies to Lane-Wells, which decided to conduct its 100,000th perforation almost 16 years later at the very same California oil well. The continued success led to new partnerships beginning in the 1950s.

A Lane-Wells merger with Dresser Industries was finalized in March 1956, and another corporate merger arrived in 1968 with Pan Geo Atlas Corporation, forming the service industry giant Dresser Atlas.

A 1987 joint venture with Litton Industries led to Western Atlas International, which became an independent company before becoming a division of Baker-Hughes in 1998 (Baker Atlas) providing well logging and perforating services. Dresser merged with Halliburton the same year.

Preserving Oil History

Connie Jones Pillsbury of Atascadero, California, and the family of Walter T. Wells wanted to preserve rare Lane-Wells artifacts. She contacted the American Oil & Gas Historical Society for help finding a home for their original commemorative album, press-clippings and guest book from the June 18, 1948, “Lane-Wells 100,000th Gun Perforating Job” event of at Montebello, California, site of a Union Oil Company La Merced No. 17 well.

Pillsbury and the children of Dale G. Jones, the grandson of Walter T. Wells, contacted petroleum museums, libraries and archives (also see Oil & Gas Families).

Pillsbury accomplished her quest to preserve the petroleum history album of Walter T. Wells. Later, she emailed AOGHS that the material became “safely archived at the USC Libraries Special Collections. Sue Luftschein is the Librarian. It’s on Online Archive of California (OAC).”

Details about the Lane-Wells collection — Gift of Connie Pillsbury, October 27, 2017 — can be accessed via the OAC website.

Title: Lane-Wells Company records

Creators: Wells, Walter T. and Lane-Wells Company

Identifier/Call Number: 7055

Physical Description: 1.5 Linear Feet 1 box

Date (inclusive): 1939-1954

The archive abstract also notes: “This small collection consists of a commemorative album celebrating the 100,000th Gun Perforating Job by the Lane-Wells Company of Los Angeles on June 18, 1948 and additional printed ephemera, 1939-1954, created and collected by Walter T. Wells, co-founder and Chairman of the Board of the Lane-Wells Company.”

Pillsbury had sought a museum or archive home for her rare oil patch artifact, which came from an event attended by many from the Los Angeles oil industry.

“The professionally-prepared book has all of the attendees signatures, photographs and articles on the event from TIME, The Oil and Gas Journal, Fortnight, Oil Reporter, Drilling, The Petroleum Engineer, Oil, Petroleum World, California Oil World, Lane-Wells Magazine, the L.A. Examiner, L.A. Daily News and L.A. Times, etc.,” Pillsbury noted in 2017.

The book, now preserved at USC, “was given to my first husband, Dale G. Jones, Ph.D., grandson of Walter T. Wells, one of the founders of Lane-Wells,” she added. “His children asked me to help find a suitable home for this book. I found you (the AOGHS website) through googling ‘History of Lane-Wells Company.’”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: 75 Years Young…BAKER-ATLAS The Future has Never Looked Brighter (2007); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields

(2007); Wireline: A History of the Well Logging and Perforating Business in the Oil Fields (1990)

(1990) . Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

. Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Lane-Wells 100,000th Perforation” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/oil-well-perforation-company. Last Updated: March 31, 2024. Original Published Date: June 30, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Aug 25, 2022 | Petroleum Technology

Petroleum pioneers who took earth science to a deeper level.

When oil burst onto the U.S. marketplace as a commercial opportunity for refining into kerosene lamp fuel, the art and science of petroleum geology was born.

The coal-mining industry had long provided employment for geologists and the oil boom presented a new kind of mineral wealth for America and a new challenge for geologists. But Pennsylvania’s first oil exploration ventures soon found that hiring geologists didn’t significantly improve their chances of success in an already risky business.

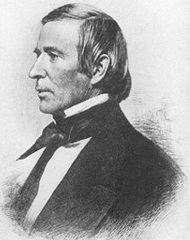

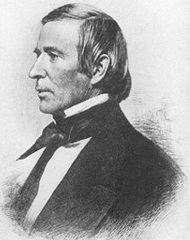

Henry D. Rogers, (1808 – 1866) was one of the first professional U.S. geologists.

Decades before the Civil War, the pursuit and mining of coal prompted many geological surveys, studies, and assessments of potential mineral resources. Railroads stretching westward needed good quality coal supplies and routes always considered the availability of nearby sources.

Oil Seeps and Salt Wells

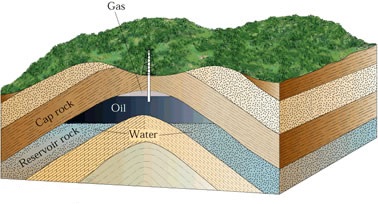

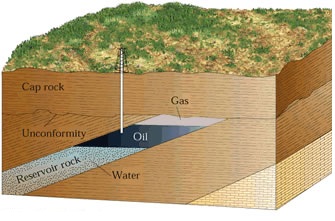

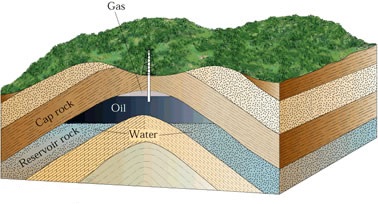

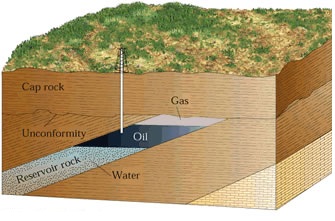

Searching for high-quality bituminous coal in America, many early geologists had reported oil seeps and the associated landforms, but mostly as a curiosity and in relation to their proximity to coal beds. In Kentucky, Ohio, and the western part of what is now West Virginia, the salt business also gave important insights into formations called “structural traps.”

Drilling commercial brine wells and salt manufacturing was a lucrative industry. Geologists’ surveys found that strata of sedimentary rock fractured, faulted, and folded, sometimes producing salt domes and brine deposits.

Geologists also noted that oil and natural gas was occasionally trapped in porous deposits sandwiched between impermeable rock layers. Such contamination fouled commercial brine wells and was an unwelcome intrusion, but cottage industry entrepreneurs skimmed it off and sold it for patent medicine, lubrication, and other novel purposes.

In Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia, geologists studied landforms associated with salt brine and coal “structural traps.” These anticlinal traps held oil and natural gas because the earth had been bent, deformed or fractured. Unsuccessfully applying structural trap theories to Pennsylvania’s differing geology undermined early petroleum geologists’ credibility.

A pioneering Ohio physician and natural scientist named Samuel Hildreth examined and recorded details of the salt business in southeastern Ohio, noting structural traps as a geologic feature associated with brine, coal, and oil.

In 1836, Hildreth published his extensive “Observations on the Bituminous Coal Deposit for the Valley of the Ohio, and the Accompanying Rock Strata.” It was America’s first petroleum geology primer.

Hildreth was a strong advocate for Ohio’s first geological survey and later served as the state geologist. His observations of the structural trapping of petroleum were later affirmed by Pennsylvania’s state geologist, Henry D. Rogers, who erroneously declared that Pennsylvania’s oilfields were likewise based on structural trapping of petroleum in anticline formations.

Pennsylvania’s oilfields were in fact found predominantly in another kind of formation altogether, the “sandstone stratigraphic trap,” but Rogers’ prestigious endorsement, circulated widely in an 1863 Harper’s Magazine article, convinced geologists to the contrary.

The search for oil prompted the first petroleum geologists to impose Hildreth and Rogers’ structural trapping theory on Pennsylvania’s differing geology. It didn’t work and their failures in Pennsylvania hindered the acceptance of petroleum geologists for decades.

Although structural trapping remains a dominant characteristic for many of America’s most prolific oil and natural gas fields, ironically it wasn’t so in Pennsylvania’s Oil Creek region, where the petroleum industry was born. As noted by author and geologist Ray Sorenson, “theories of trapping did not work in the absence of anticlines.”

Sorenson, who has researched first documented reports of oil worldwide (see Earliest Signs of Oil), also reported the science of petroleum geology took some time to develop — and be accepted.

The dominant oil bearing feature in Pennsylvania’s oil region is a sedimentary geologic formation known as a “stratigraphic trap” and differs significantly from a structural trap. It is formed in place by erosion, usually in porous sandstone enclosed in shale. The impermeable shale keeps the oil and gas from escaping.

It took until the turn of the century before successful geologically driven discoveries in the Mid-Continent and Gulf regions encouraged exploration companies to use petroleum geologists.

Although the science of geology had revealed the 34-square-mile El Dorado oilfield in central Kansas in 1915, many companies still had little confidence in geologists.

James C. Donnell, president of the Ohio Oil Company (later Marathon Oil) proclaimed, “The day The Ohio has to rely on geologists, I’ll get into another line of work.”

But after the company’s first geologist, C.J. “Charlie” Hares found 19 oil and natural gas fields, Donnell changed his mind and declared Hares to be “the greatest geologist in the world.”

AAPG inspires professional conduct amongst its more than 30,000 members.

Increasing understanding and acceptance of petroleum geology as a valued tool in exploration led to the 1917 formation of the Southwestern Association of Petroleum Geologists, precursor to today’s American Association of Petroleum Geologists. Since then, AAPG has fostered scientific research, advanced the science of geology, and promoted new technologies.

Father of American Geology

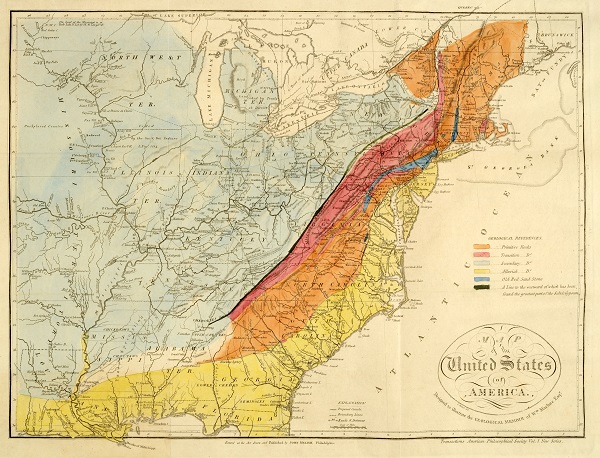

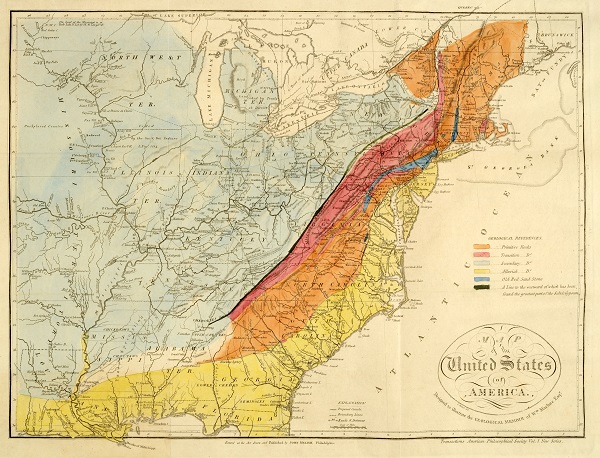

Born in Ayr, Scotland, William Maclure (1863-1840) created the earliest geological maps of North America, becoming a renowned American geologist and “stratigrapher.” Many geologists consider Maclure the Father of American Geology.

“Map of the United States of America, Designed to Illustrate the Geological Memoir of Wm. Maclure, Esqr.” This 1818 version is more detailed than the first geological map he published in 1809. Image courtesy the Historic Maps Collection, Princeton Library.

Maclure settled in the United States in 1797, and by 1808 he had traveled from Maine to Georgia to produce the first U.S. geological map, published in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. “Here, in broad strokes, he identifies six different geological classes,” a Princeton geologist later reported. “Note that the chain of the Appalachian Mountains is correctly labeled as containing the most primitive, or oldest, rock.”

When Yale chemist Benjamin Silliman organized the American Geological Society in 1819, Maclure was elected its first president. In the 1850s, Silliman’s son, also a Yale chemist, analyzed samples of Pennsylvania “rock oil” for refining into kerosene. His report led to drilling America’s first oil well in 1859.

Father of Petroleum Engineering

John Franklin Carll, a geologist born in Bushwick, New York, on May 7, 1828, could be considered the world’s first petroleum engineer. He developed many of the exploration and production industry’s geological methods — and helped pioneering oil driller Lyne Taliaferro Barret drill the first Texas oil well.

“In 1875, Carll published strip logs from nine Pennsylvania wells, and he used them for correlation purposes in much the same manner as they are employed today,” noted the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE). “His work also confirmed the theory that oil sands lie in lens-shaped masses, not in continuous belts, and that oil does not occur in underground pools or lakes, but in pores of sandstone.”

“More than a century ago, he expressed the principles of petroleum engineering and geology that established much of the framework for the development of petroleum engineering technology,” proclaimed SPE, which established the John Franklin Carll Award in 1958.

The earth sciences of petroleum geology and engineering have come a long way since pioneering steps and stumbles in the Ohio River Valley and Pennsylvania’s early oilfields. Modern geologists grapple with vast amounts of data and technological innovations in pursuit of petroleum.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017); The Natural Gas Industry in Appalachia (2005); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2005); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an annual AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology.” Authors: B.W. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/petroleum-geologys-rocky-beginnings. Last Updated: October 24, 2022. Original Published Date: February 14, 2016.

(1984); Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum

(2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.