by Bruce Wells | Jan 8, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

The North Texas church once proclaimed as richest in America.

In the fall of 1917 near Ranger, Texas, the cotton-farming town of Merriman was inhabited by “ranchers, farmers, and businessmen struggling to survive an economic slump brought on by severe drought and boll weevil-ravaged cotton fields.”

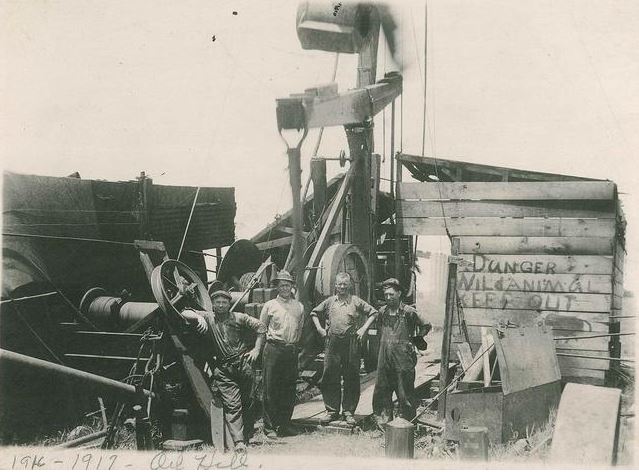

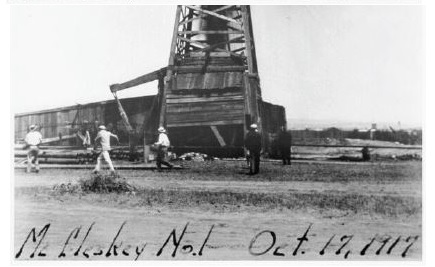

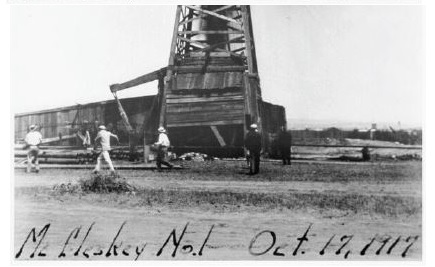

Everything changed in Eastland County when a wildcat well drilled by Texas & Pacific Coal Company struck oil at Ranger, four miles from Merriman. The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 well produced 1,600 barrels of oil a day.

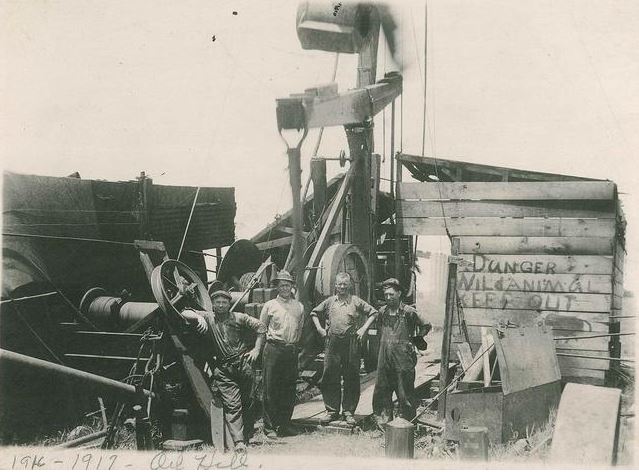

McCleskey No. 1 cable-tool oil well, the “Roaring Ranger” gusher of 1917, brought an oil boom to Eastland County, Texas, about 100 miles west of Dallas.

The rush to acquire leases that followed the oilfield discovery became legendary among drilling booms, even for Texas, home of the 1901 “Lucas Gusher” on Spindletop Hill at Beaumont.

As drilling continued, yield of the Ranger oilfield led to peak production reaching more than 14 million barrels in 1919. Production from the “Roaring Ranger” well and its giant North Texas oilfield helped win World War I — with a British War Cabinet member declaring, “the Allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil.”

Texas & Pacific Coal Company had taken a great risk by leasing acreage around Ranger, but the risk paid off when lease values soared. The exploration company added “oil” to its name, becoming the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

“So as we could not worship God on the former acre of ground, we decided to lease it and honor God with the product,” explained Merriman Baptist Church Deacon J.T. Falls. Photo courtesy Robert Vann, “Lone Star Bonanza, the Ranger Oil Boom of 1917-1923.”

The price of the oil company stock jumped from $30 a share to $1,250 a share as a host of landmen, “scanned the landscape to discover any fractions in these holdings. A little school and church, before too small to be seen, now looked like a sky scraper.”

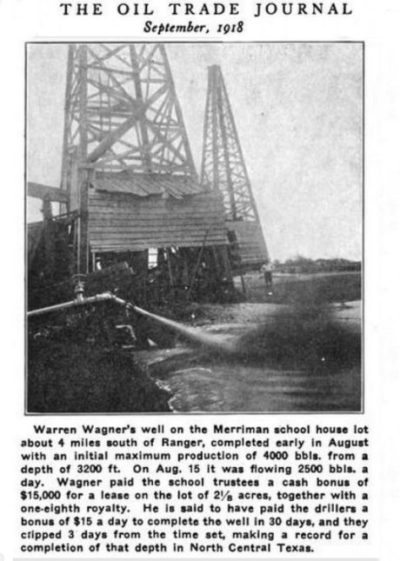

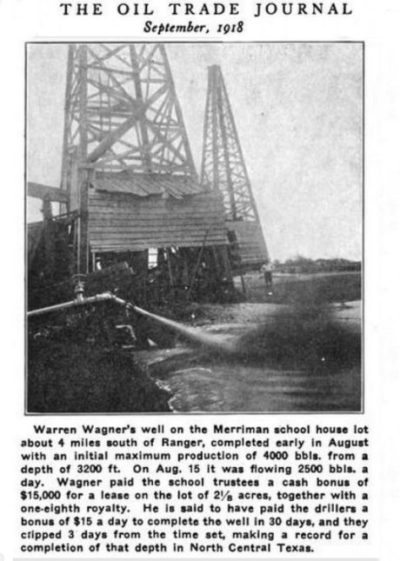

Warren Wagner, driller of the McCleskey discovery well, leased the local school lot and in August 1918 completed a well producing 2,500 barrels of oil a day. Leasing at Merriman Baptist Church proved to be a challenge.

In February, Deacon J.T. Falls complained drilling new wells, “ran us out, as all of the land around our acre was leased, producing wells being brought in so near the house we were compelled to abandon the church because of the gas fumes and noisy machinery.”

Falls added that, “So as we could not worship God on the former acre of ground, we decided to lease it and honor God with the product.”

Deacon J.T. Falls (second from left) was not amused when the Associated Press reported in 1919 that his church had refused a million dollars for the lease of the cemetery.

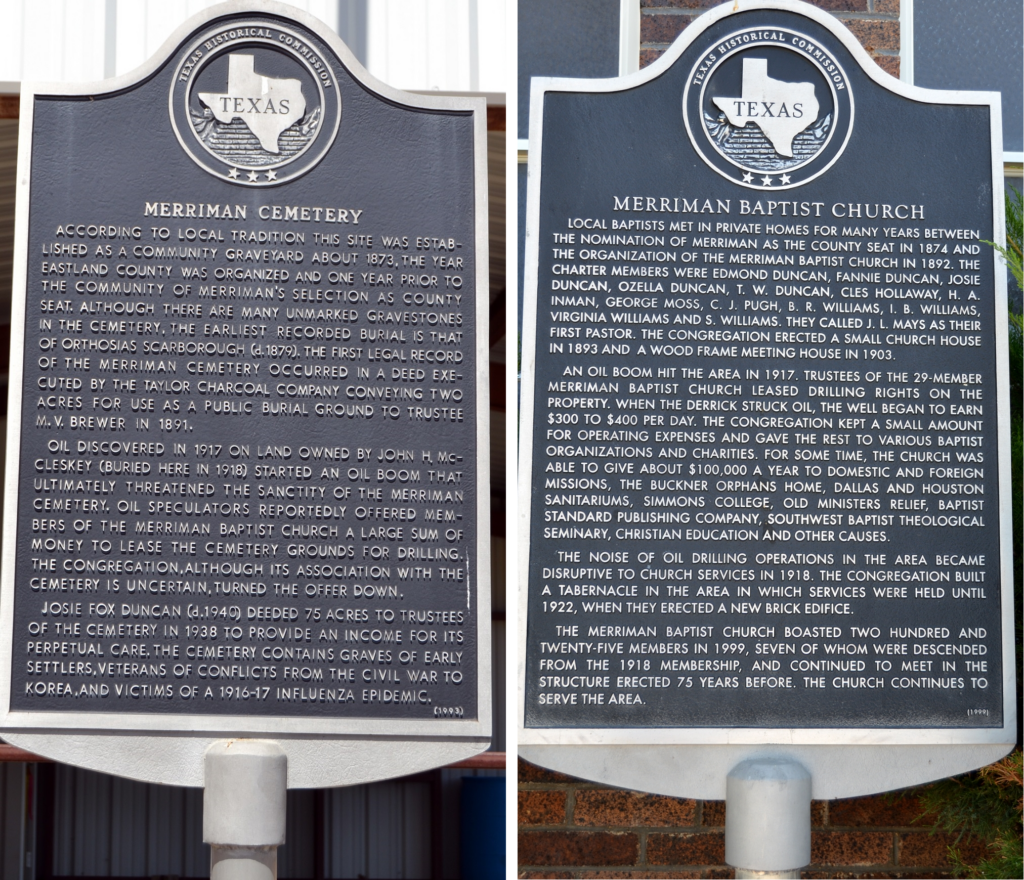

A Texas Historical Commission marker erected in 1999 described when the well on the church’s lease began producing oil, earning the congregation a royalty of between $300 and $400 a day. Merriman Baptist Church, “kept a small amount for operating expenses and gave the rest to various Baptist organizations and charities.”

However, drilling in the church graveyard was a different matter. As oil production continued to soar in North Texas, the congregants of Merriman Baptist Church initially resisted one drilling drilling site. As a January 18, 1919, article in the New York Times noted in its headline, “CHURCH MADE RICH BY OIL; Refuses $1,000,000 for Right to Develop Wells in Graveyard.”

Respecting the Dead

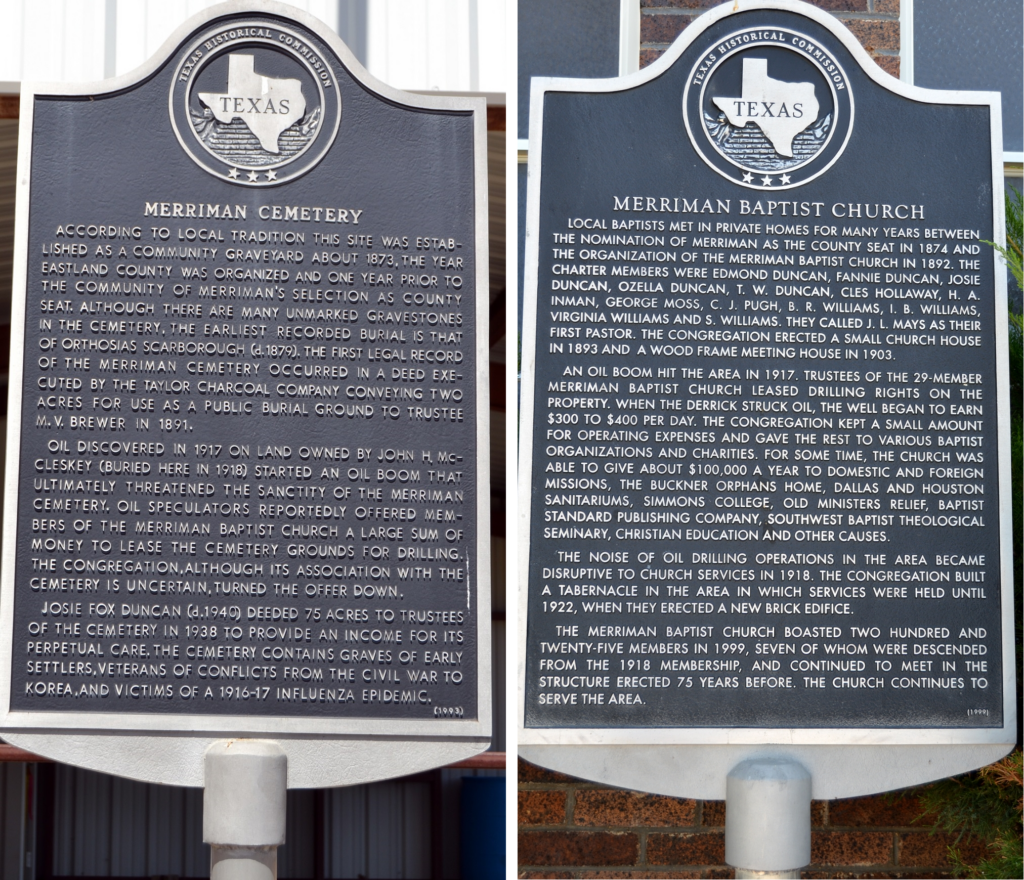

At Merriman’s church cemetery, a less seen historical marker erected in 1993 explains the drilling boom’s fierce competition to find property without a well already on it: “Oil speculators reportedly offered members of the Merriman Baptist Church a large sum of money to lease the cemetery grounds for drilling.”

Near Ranger in Eastland County, Texas Historical Commission markers erected in 1993 (left) and 1999 explaining how members of the Merriman Baptist Church shared their wealth from petroleum royalties. Photos courtesy the Historical Marker Database.

When local newspapers reported the church had refused an offer of $1 million, the Associated Press picked it up and newspapers from New York to San Francisco ran the story. Literary Digest even featured, “the Texas Mammon of Righteousness” with a photograph of the “The Congregation That Refuses A Million.”

Deacon J.T. Falls was not amused. “A great many clippings have been sent to us from many secular papers to the effect that we as a church have refused a million dollars for the lease of the cemetery. We do not know how such a statement started,” the deacon opined.

“The cemetery does not belong to the church. It was here long before the church was. We could not lease it if we would and we would not if we could,” the cleric added.

“If any person’s or company’s heart has become so congealed as to want to drill for oil in this cemetery, they could not – for the dead could not sign a lease and no living person has any right to do so,” Falls proclaimed.

The church deacon concluded with an ominous admonition to potential drillers, “Those that have friends buried here have the right and the will to protect the graves and any person attempting to trespass will assume a great risk.”

A 1918 article noted a “Merriman school house” oil well drilled to 3,200 feet in record time for North Central Texas.

Roaring Ranger’s oil production dropped precipitously because of dwindling reservoir pressures brought on by unconstrained drilling. Many exploration and production companies failed (including fraudulent ones like Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company).

In the decades since the McCleskey No. 1 well, advancements in horizontal drilling technology have presented more legal challenges to mineral rights of the interred, according to Zack Callarman of Texas Wesleyan School of Law.

Callarman wrote an award-winning analysis of laws concerning drilling to extract oil and natural gas underneath cemeteries. “Seven Thousand Feet Under: Does Drilling Disturb the Dead? Or Does Drilling Underneath the Dead Disturb the Living?” was published in the Real Estate Law Journal in 2014.

Despite yet another North Texas oilfield discovery at Desdemona, by 1920 the Eastland County drilling boom was over. The faithful still gather at Merriman Baptist Church every Sunday.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Texas Oil: A Photographic History, 1866-1936

(2000);Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2000);Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History (2013);Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(2013);Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen (1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Riches of Merriman Baptist Church.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/oil-riches-of-merriman-baptist-church. Last Updated: January 12, 2025. Original Published Date: January 18, 2019.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 10, 2024 | Petroleum History Almanac

Grandfather scouted Philadelphia streets for earliest gas station locations.

Seeking to preserve heirlooms, families often turn to local museums, colleges, and historical societies for help. When related to petroleum business careers, the American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) website maintains updated links to special resources, community oil and gas museums, and some help for researching old oil company stock certificates.

A petroleum industry artifact on the AOGHS Oil & Gas Families page has its own connection with refining history — and is an heirloom in search of an permanent home.

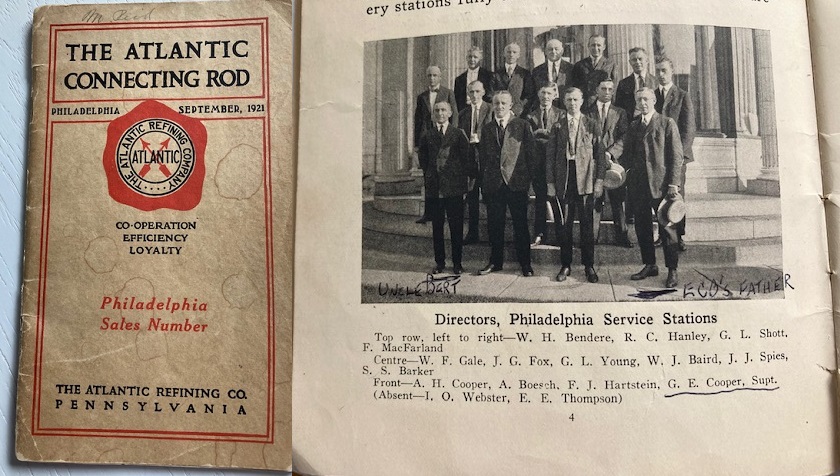

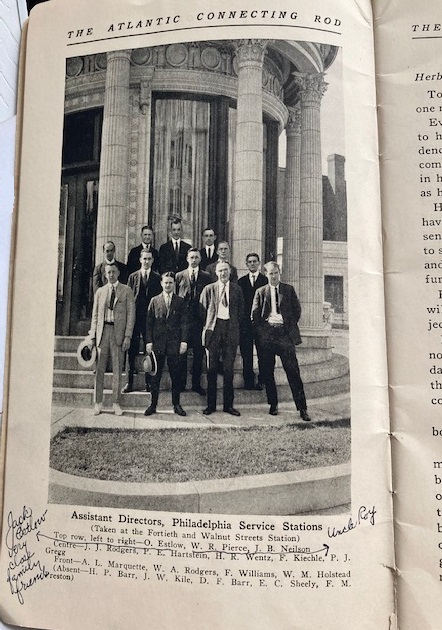

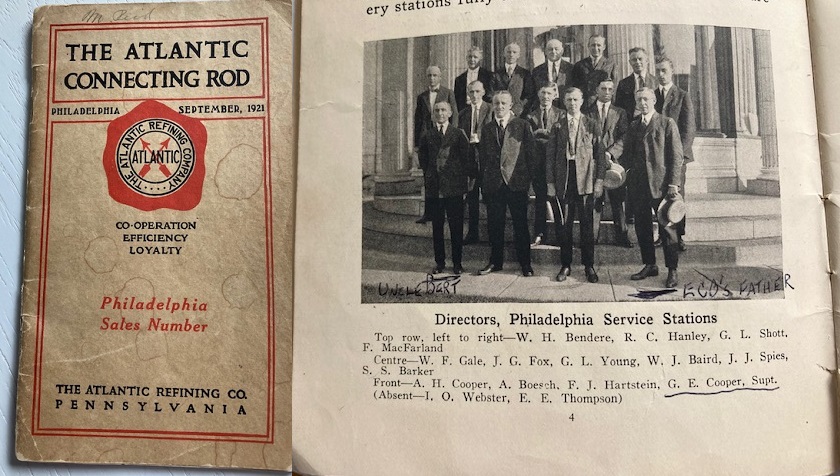

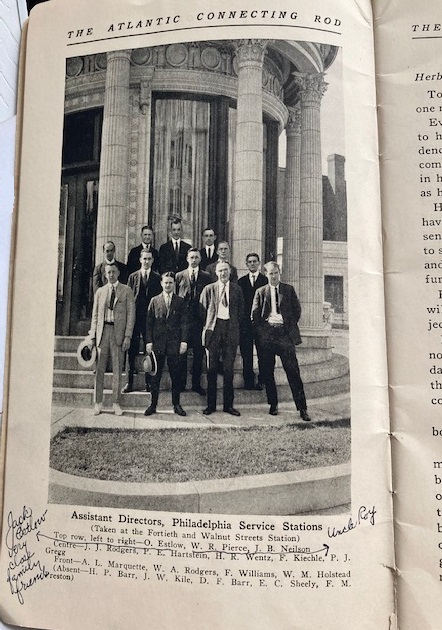

“I have an old Atlantic Richfield brochure that I’d be glad to donate to any interested party,” Jane Benner noted in a June 2022 email to AOGHS. “My grandfather (G.E. Cooper) and his brother (Albert Cooper) as well as a future brother-in-law (W.R. Pierce) are pictured among the staff salesmen and administrators. The handwriting identifying them is that of my grand mother, Eleanor Cooper Benner.”

The Atlantic Connecting Rod

Seeking advice for locating a suitable museum or archive, Benner attached the cover and interior photos from her family’s 1921 issue of “The Atlantic Connect Rod” (perhaps an employee publication of the Atlantic Refining Company). The Philadelphia-based venture incorporated in 1870 to refine lamp kerosene and other petroleum products.

Jane Benner’s grandfather George Edward Cooper stands among other Atlantic Refining Company salesmen and administrators in 1921.

Taken over by John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust by the end of the 20th century, Atlantic Refining Company returned as an independent company following the U.S. Supreme Court’s dissolution of the monopoly in 1911.

With its South Philadelphia refinery among the largest in the United States, in 1966 Atlantic Refining merged with Richfield Oil Corporation, creating the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO). Two years later, the new major oil company made the first oil discovery in Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay, leading to construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in the mid-1970s.

Early Philly Gas Stations

“All I know of my grandfather’s work is that he was responsible for identifying locations to open gas stations in Philadelphia (right side of the road, heading out of town, as my mother told me). He died in 1927, so likely his work there was during the 1910s and 1920s,” Benner explained.

The Gulf Refining Company had opened America’s first gas station in Pittsburgh in late 1913, and three years later, the company’s “Good Gulf Gasoline” also went on sale in West Philadelphia.

The Atlantic Refining publication features Albert Cooper, brother of Jane Benner’s grandfather, as well as a future brother-in-law (W. R. Pierce). The handwriting identifying them is that of her mother, Eleanor Cooper Benner.

The Gulf station opening at 33rd and Chestnut streets was the start of the “Battle for Gasadelphia,” according to PhillyHistory. In April 1916, Gulf added a second station at at Broad Street and Hunting Park Avenue.

“How did the competition respond? The Philadelphia and Pittsburgh-based Atlantic Refining Company formed a committee to brainstorm,” the 2013 blog noted. Gulf Refining’s first station used a distinctive pagoda style architecture. More designs would emerge to attract consumers.

Both refining companies used service station location and architecture to explore the earliest combinations of integrating functionalism with new or classical designs, noted Keith A. Sculle in his 2004 article, “Atlantic Refining Company’s Monumental Service Stations in Philadelphia, 1917-1919,” published in the Journal of American & Comparative Cultures (see Wiley Online Library).

Preserving Oil History

To find a home for her family’s Atlantic Refining artifact, Benner has been contacting Pennsylvania museums while researching more about the company and her grandfather’s career. She hopes her small but meaningful family heirloom will be preserved as part of America’s petroleum history.

“The booklet is remarkably informative about the company and their sales objectives at that time, including locations and photos of the early stations,” Benner noted in her email to AOGHS. “It’s fine to post my family story, as sparse as it is,” concluded the granddaughter of G.E. Cooper.

Benner added that she planned on contacting curators and archivists at oil museums, “in case anyone is interested.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: An Illustrated Guide to Gas Pumps (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Preserving a 1921 Atlantic Refining Publication.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/laviness-family-oilfield-history. Last Updated: July 12, 2022. Original Published Date: July 12, 2022.

by Bruce Wells | Aug 5, 2024 | Petroleum Companies, Petroleum History Almanac

Searching for petroleum wealth in risky Mid-Continent fields.

The Kansas petroleum industry began in 1892 with an oilfield at Neodesha. In 1915, an oilfield discovery at El Dorado near Wichita revealed the giant Mid-Continent field, but it took years for business sense to arrive, according to the editor of a 1910 History of Wichita and Sedgwick County, Kansas.

The new science of petroleum geology helped reveal the Mid-Continent’s giant El Dorado oilfield in 1915. Photo courtesy Kansas Oil Museum.

“Sedgwick county has run the gamut of the hot winds, the drought, the floods, the grasshoppers, the boom, the wild unreasoning era of speculation, the land grafters, the oil grafters, the sellers of bogus stocks, speculation, over-capitalization, and all of the attendant and kindred evils,” observed Editor-in-Chief Orsemus Bentley. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Feb 20, 2024 | Petroleum History Almanac

Determined and skilled workforce inspires more to join them.

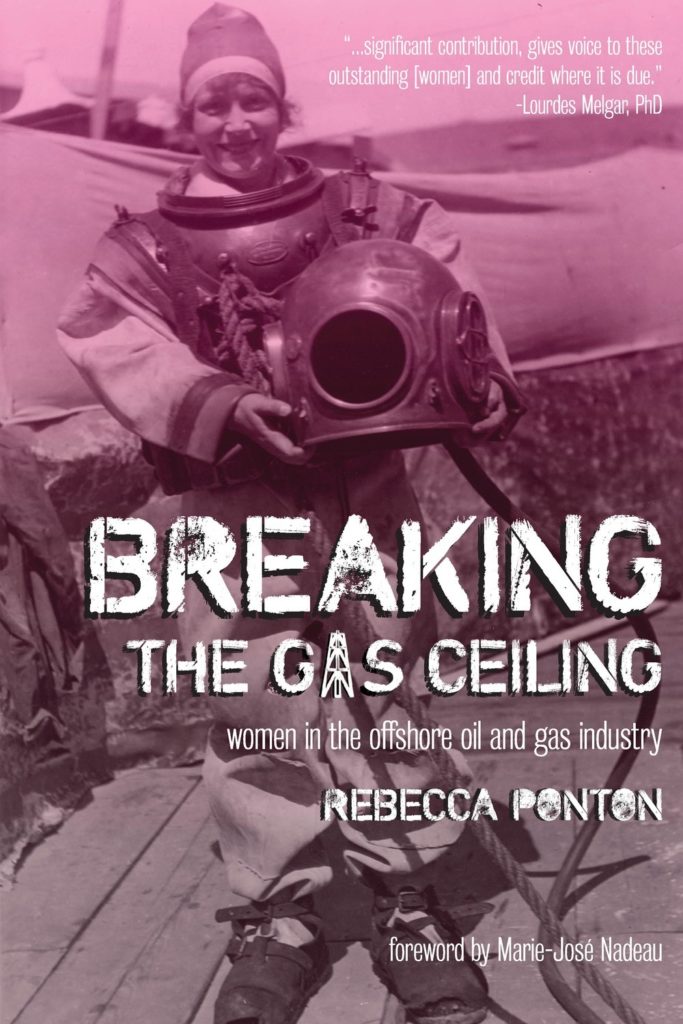

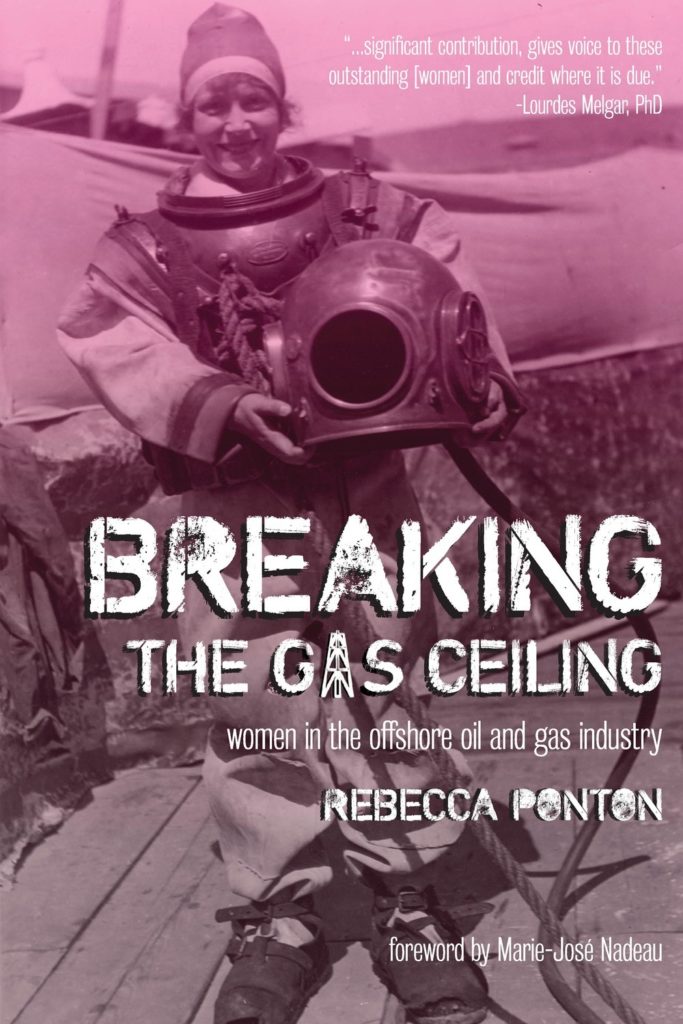

A 2019 book documents remarkable stories of women working in the petroleum industry and offers insights beyond the history of offshore exploration.

In Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry, journalist Rebecca Ponton has assembled a rare collection of personal accounts from pioneering women who challenged convention, stereotypes, and more to work in the offshore oil and natural gas industry.

Journalist Rebecca Ponton has researched and written “condensed biographies” of 23 women — all of them offshore industry pioneers

Like their onshore oilfield counterparts of all genders, these ocean roughnecks include petroleum engineers, geologists, landmen — and an increasing number of CEOs.

Offshore Pioneers

Ponton’s Breaking the Gas Ceiling, published by Modern History Press in 2019, tells the stories of the industry’s “WOW — Women on Water,” the title of her introductory chapter.

What follows are “condensed biographies” of 23 women of all ages and nationalities. Their petroleum industry jobs have varied in responsibilities — and many of the women achieved a “first” in their fields.

Ponton, herself a professional landman, interviewed this diverse collection of energy industry professionals, producing an “outstanding compilation of role models,” according to Dave Payne, vice president, Chevron Drilling and Completions.

“Everyone needs role models — and role models that look like you are even better. For women, the oil and gas industry has historically been pretty thin on role models for young women to look up to,” noted the Chevron executive. “Rebecca Ponton has provided an outstanding compilation of role models for all women who aspire to success in one of the most important industries of modern times.”

Each chapter offers an account of finding success in the traditionally male-dominated industry — sometimes with humor but always with determination.

Among the offshore jobs described are stories from mechanical and chemical engineers, a helicopter pilot, a logistics superintendent, a photographer, fine artist, federal offshore agency director, and the first female saturation diver in the Gulf of Mexico — Marni Zabarski, who describes her career and 2001 achievement.

Additional insights are provided from water safety pioneer Margaret McMillan (1920-2016), who in 1988 was instrumental in creating the Marine Survival Training Center at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Offshore oil and natural gas platforms typically seen at the Port of Galveston, Texas. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Most U.S. offshore oil and natural gas leasing and development activity takes place in the central and western Gulf of Mexico — with thousands of platforms operating in waters up to 6,000 feet deep. McMillan in 2004 became the first woman to be inducted into the Oilfield Energy Center’s Hall of Fame in Houston.

Another of Ponton’s chapters features 2018 Hall of Fame inductee Eve Howell, a petroleum geologist who was the first woman to work — and eventually supervise — production from Australia’s prolific North West Shelf. The book also relates the story of 21-year-old Alyssa Michalke, an Ocean Engineering major who was the first female commander of the Texas A&M Corps of Cadets.

As the publisher Modern History Press explained, Ponton offers insights beyond documenting remarkable women in petroleum history. “In order to reach as wide an audience as possible, including the up and coming generation of energy industry leaders, Rebecca made it a point to seek out and interview young women who are making their mark in the sector as well.”

The milestones of these notable “women on water” may not receive the attention given to NASA’s women spacewalkers, but they also deserve recognition. Today’s offshore petroleum industry needs all the skilled workers it can get of any gender. The too often neglected oilfield career histories told in Breaking the Gas Ceiling should help.

Also see Women Oilfield Roustabouts.

______________________

Recommended Reading: Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019); Offshore Pioneers: Brown & Root and the History of Offshore Oil and Gas (1997); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1997); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Women of the Offshore Petroleum Industry tell Their Stories.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/women-of-the-offshore-petroleum-industry-tell-their-stories. Last Updated: December 20, 2024. Original Published Date: February 18, 2020.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 12, 2024 | Petroleum History Almanac

by Bruce Wells | Oct 14, 2023 | Petroleum History Almanac

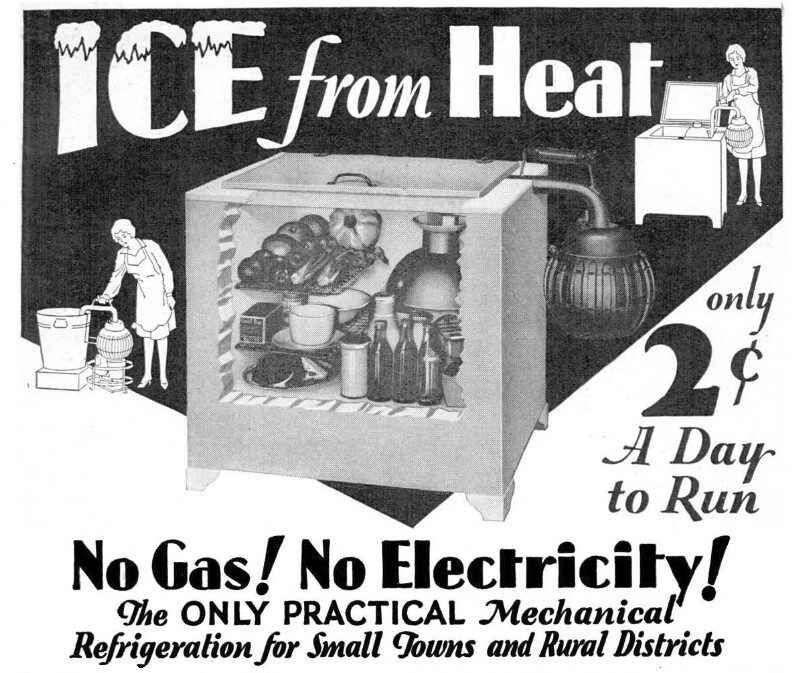

Crosley Radio Company’s kerosene-heated refrigeration appliance for rural America.

Only three percent of U.S. farms had electricity in 1925, according to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

For most of rural America in the early 20th century, kerosene lamps extended the day. On some farms, battery-powered radios brought news and entertainment at night.

By 1927, Crosley Radio Company reported sales of $18 million — making it the largest radio manufacturer in the world.

Crosley radios were marketing with the slogan, “You’re There With A Crosley.” Founded in the early 1920s by Powel Crosley Jr., the Cincinnati-based corporation became known for innovative engineering.

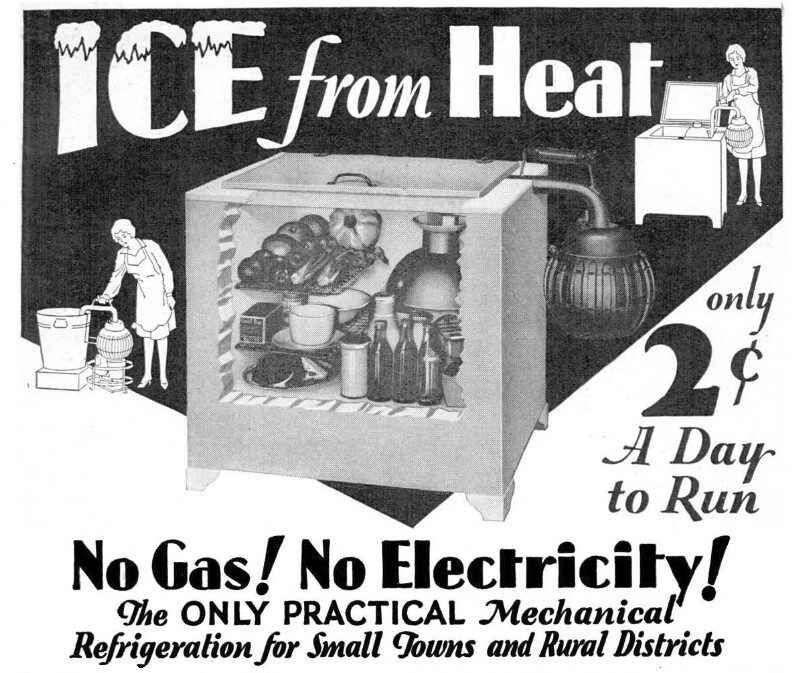

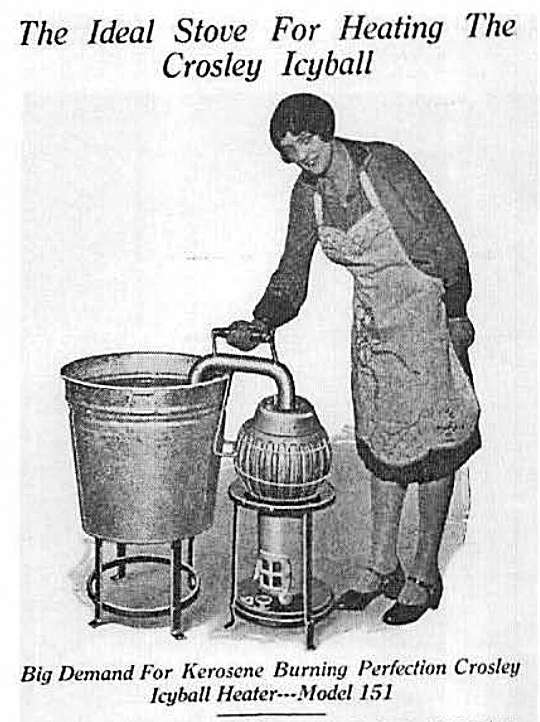

Production of Crosley Radio’s Icy Ball refrigerator began in 1928, and the Icy Ball sold for about $80, complete with a 4.25 cubic foot cabinet.

Crosley, sometimes called “The Henry Ford of Radio,” would expand the company into manufacturing automobiles, aircraft, and home appliances.

He also recognized a lucrative market awaited in the millions of farm homes lacking electricity, not just for radio, but for his company’s first venture into refrigeration.

Crosley Icy Ball — Heated Refrigeration

Built on earlier patents developed for absorption refrigeration and assigned to Crosley, the radio company began production of a new appliance, promoting the device’s simplicity, durability, and economy.

With no moving parts, the Crosley Icy Ball (or Icyball) was designed to chill by using intermittent heat absorption with a water ammonia mixture as the refrigerant.

Once “charged” by heating for 90 minutes with a cup of kerosene, an Icy Ball could provide a day or more of refrigeration, plus a few ice cubes. No electricity required.

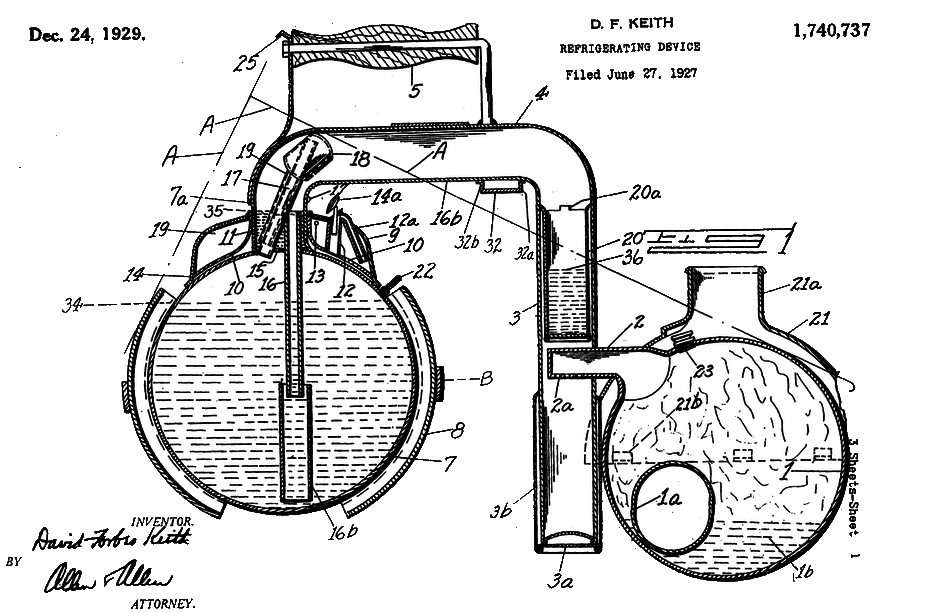

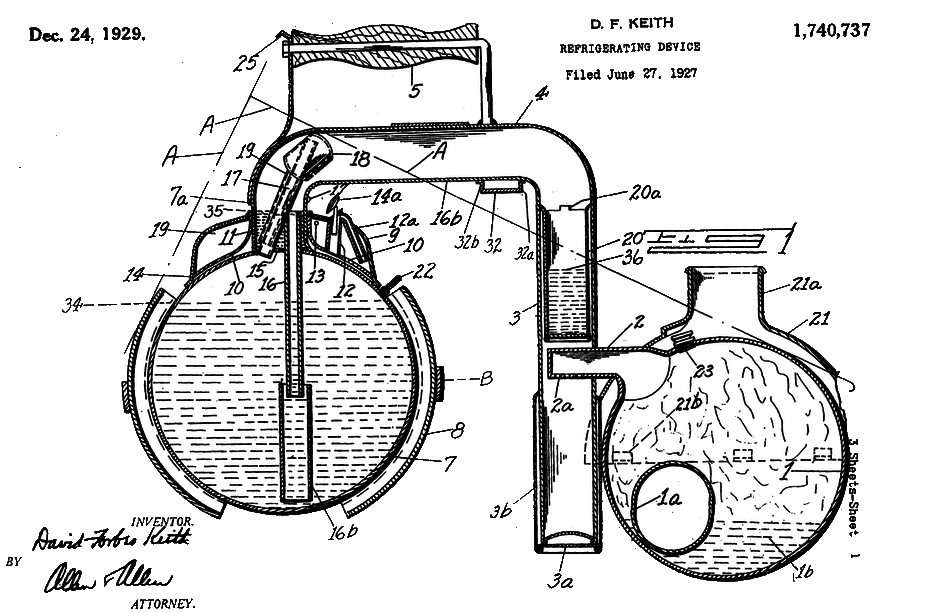

Crosley Radio Corporation bought the rights to the “icy ball” refrigeration idea from David Keith of Canada, who had applied for a U.S. patent in June 1927.

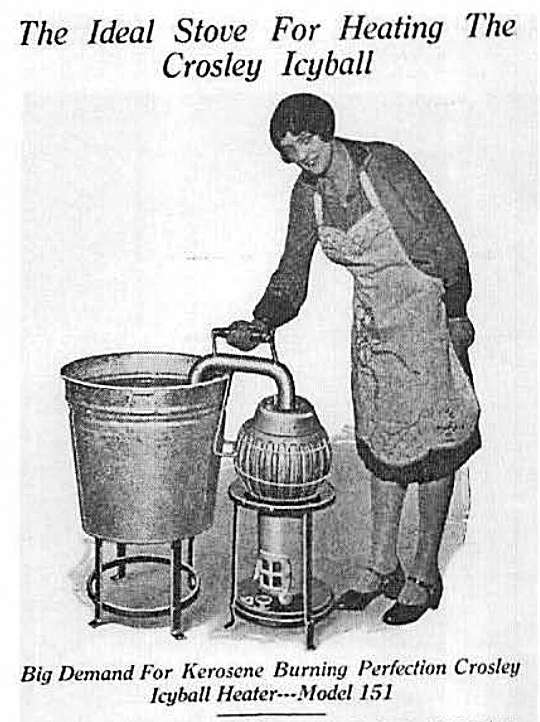

Crosley Radio’s new refrigerating appliance was simple to operate, much like Standard Oil’s “Perfection” stove and similar kerosene stoves, along with the Monitor Sad Iron Company’s popular gasoline iron.

“Especially for women in rural and farm households, kerosene provided an important bridge fuel to the newer age of gas and electricity. To ignore it is to ignore what was for many an important introduction to modern times,” explained Mark Aldrich in Agricultural History Journal, Winter 2020, “The Rise and Decline of the Kerosene Kitchen.”

Heated with a kerosene stove, the Crosley icy ball chilled by using intermittent heat absorption with a water ammonia mixture as the refrigerant.

Crosley Radio’s instructions for the “Icyball Refrigerator” stated, “The Perfection kerosene stove has been designed especially for the Icyball and is recommended.”

Production of the Crosley Icy Ball began in 1928, and it sold for about $80, complete with a 4.25 cubic foot cabinet. Crosley Radio declared sales of 22,000 for the refrigeration appliance in the first year alone.

“Refrigeration – everyday necessity to household economy and family health – is possible now WITHOUT ELECTRICITY – at a cost so low that about 2 cents a day covers it everywhere,” proclaimed company advertisements.

Rural Electrification Act

The New Deal’s Rural Electrification Act of 1936 empowered the federal government to make low-cost loans to farmers bringing electricity to rural America.

Among the most successful of President Franklin Roosevelt’s programs, the loans allowed thousands of farms to exploit the labor savings that electric lights, tools, and appliances could bring. Electrification grew from only 3.2 percent in 1925, to 90 percent by 1950.

Crosley adapted to the electrified market and made an even bigger hit with its 1933 refrigerator, the “Shelvador” Model D-35, which featured the unheard of innovation of door shelving and automatic interior lighting within its three and a half cubic feet. More electric appliances followed, and for decades the company remained preeminent in refrigerators.

Electrification of rural America rendered Crosley Icy Balls obsolete and production ended in 1938, but Crosley Radio endured.

Smithsonian Icy Ball Exhibit

Powel Crosley Jr. bought the rights to the icy ball refrigeration design from David Keith of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, who had applied for a patent in June 1927 and received it on December 24, 1929 (No. 1,740,737). Crosley Radio improved the device while acquiring additional patents.

Crosley Radio Corporation sold thousands of Icy Ball refrigeration appliances (with ice maker) before production ended in 1938.

Although not on display, a Crosley Icy Ball has been preserved at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Refrigeration artifact (No. 1988.0609.01) was tested in 1998 and successfully completed a heat charge cycle, producing a temperature of 18 degrees Fahrenheit.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Crosley Icy Ball Refrigerator.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/crosley-icy-ball-refrigerator. Last Updated: October 14, 2023. Original Published Date: October 14, 2023.

(2000);Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2013);Wildcatters: Texas Independent Oilmen

(1984). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.