by Bruce Wells | Jan 6, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

January 7, 1864 – Oilfield Discovery at Pithole Creek –

The once famous Pithole Creek oilfield was discovered in Pennsylvania with the United States Petroleum Company’s well reportedly located using a witch-hazel dowser. The discovery well, which initially produced 250 barrels of oil a day, brought a “black gold” rush as boom town Pithole made headlines five years after the first U.S. oil well drilled at nearby Titusville.

oilfield was discovered in Pennsylvania with the United States Petroleum Company’s well reportedly located using a witch-hazel dowser. The discovery well, which initially produced 250 barrels of oil a day, brought a “black gold” rush as boom town Pithole made headlines five years after the first U.S. oil well drilled at nearby Titusville.

Boom town Pithole City’s history is preserved at Pennsylvania’s Oil Creek State Park. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Adding to the boom were Civil War veterans eager to invest in the new industry. Newspaper stories added to the oil fever — as did the Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny.” Tourists today visit Oil Creek State Park and its education center on the grassy expanse that was once Pithole.

January 7, 1905 – Humble Oilfield Discovery rivals Spindletop

C.E. Barrett discovered the Humble oilfield in Harris County, Texas, with his Beatty No. 2 well, which brought another Texas drilling boom four years after Spindletop launched the modern petroleum industry. Barrett’s well produced 8,500 barrels of oil per day from a depth of 1,012 feet.

The population of Humble jumped from 700 to 20,000 within months as production reached almost 16 million barrels of oil, the largest in Texas at the time. The field directly led to the 1911 founding of the Humble Oil Company by a group that included Ross Sterling, a future governor of Texas.

An embossed postcard circa 1905 from the Postal Card & Novelty Company, courtesy the University of Houston Digital Library.

“Production from several strata here exceeded the total for fabulous Spindletop by 1946,” notes a local historic marker. “Known as the greatest salt dome field, Humble still produces and the town for which it was named continues to thrive.” Another giant oilfield discovery in 1903 at nearby Sour Lake helped establish the Texaco Company.

Humble Oil, renamed Humble Oil and Refining Company in 1917, consolidated operations with Standard Oil of New Jersey two years later, eventually leading to ExxonMobil.

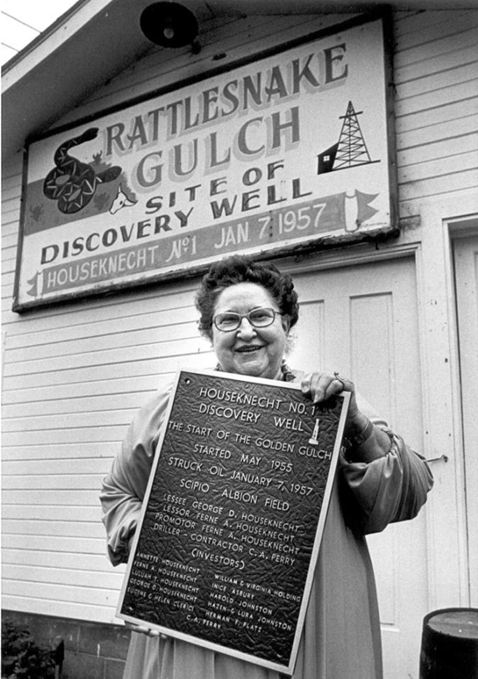

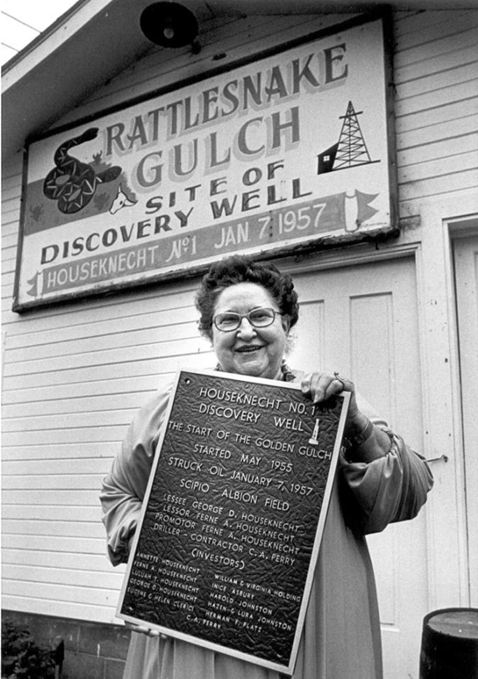

January 7, 1957 – Michigan Dairy Farmer finds Giant Oilfield

After two years of drilling, a wildcat well on Ferne Houseknecht’s Michigan dairy farm discovered the state’s largest oilfield. The 3,576-foot-deep well produced from the Black River formation of the Trenton zone.

After 20 months of on-again, off-again drilling, Ferne Houseknecht’s well revealed a giant oilfield in the southern Michigan basin.

The Houseknecht No. 1 discovery well at Rattlesnake Gulch revealed a producing region 29 miles long and more than one mile wide. It prompted a drilling boom that led to production of 150 million barrels of oil and 250 billion cubic feet of natural gas from the giant Albion-Scipio field in the southern Michigan basin.

“The story of the discovery well of Michigan’s only ‘giant’ oilfield, using the worldwide definition of having produced more than 100 million barrels of oil from a single contiguous reservoir, is the stuff of dreams,” noted Michigan historian Jack Westbrook in 2011.

in 2011.

Learn more in Michigan’s “Golden Gulch” of Oil.

January 7, 1913 – “Cracking” Patent improves Refining

William Burton of the Standard Oil Company’s Whiting, Indiana, refinery received a patent for a process that doubled the amount of gasoline produced from each barrel of oil refined. Burton’s invention came as gasoline demand was rapidly growing with the popularity of automobiles. His thermal cracking concept was an important refining advancement, although the process would be superseded by catalytic cracking in 1937.

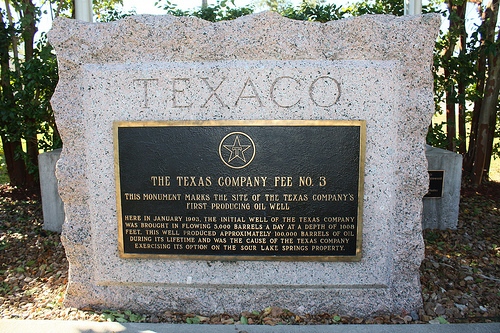

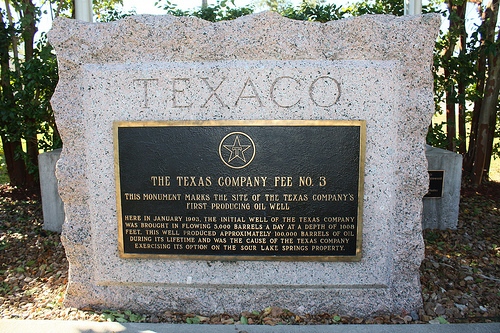

January 8, 1903 – Sour Lake discovery leads to Texaco

Founded a year earlier in Beaumont, Texas, the Texas Company struck oil with its Fee No. 3 well, which flowed at 5,000 barrels a day, securing the company’s success in petroleum exploration, production, transportation and refining.

A monument marks the site where the Fee No. 3 well flowed at 5,000 barrels of oil a day in 1903, helping the Texas Company become Texaco.

“After gambling its future on the site’s drilling rights, the discovery during a heavy downpour near Sour Lake’s mineral springs, turned the company into a major oil producer overnight, validating the risk-taking insight of company co-founder J.S. Cullinan and the ability of driller Walter Sharp,” explained a Texaco historian. The Sour Lake field — and wells drilled in the Humble oilfield two years later — led to the Texas Company becoming Texaco (acquired by Chevron in 2001).

Learn more in Sour Lake produces Texaco.

January 10, 1870 – Rockefeller incorporates Standard Oil Company

John D. Rockefeller and five partners incorporated the Standard Oil Company in Cleveland, Ohio. The new oil and refining venture immediately focused on efficiency and growth. Instead of buying barrels, the company bought tracts of oak timber, hauled the dried timber to Cleveland on its own wagons, and built its own 42-gallon oil barrels.

A stock certificate issued in 1878 for Standard Oil Company, which would become Standard Oil of Ohio (Sohio) following the 1911 breakup of John D. Rockefeller’s oil monopolies.

Standard Oil’s cost per wooden barrel dropped from $3 to less than $1.50 as the company improved refining methods to extract more kerosene per barrel of oil (there was no market for gasoline). By purchasing properties through subsidiaries, dominating railroads and using local price-cutting, Standard Oil captured 90 percent of America’s refining capacity.

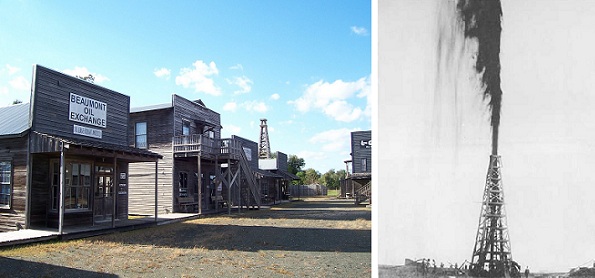

January 10, 1901 – Spindletop launches Modern Petroleum Industry

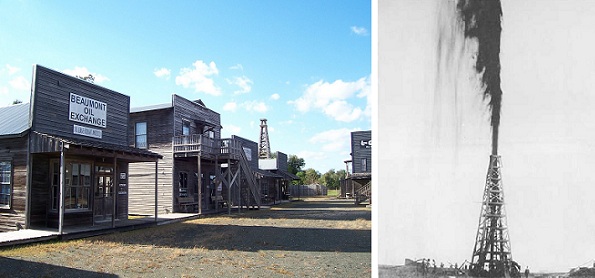

The modern U.S. oil and natural gas industry began 123 years ago on a small hill in southeastern Texas when a wildcat well erupted near Beaumont. The Spindletop field, which yielded 3.59 million barrels of oil by the end of 1901, would produce more oil in one day than all the rest of the world’s oilfields combined.

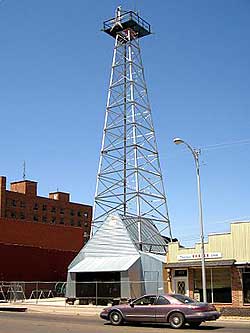

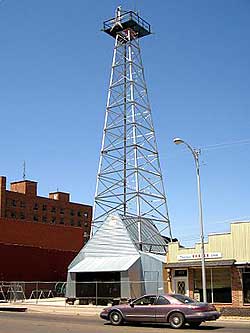

The Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum in Beaumont, Texas, opened in 1976 to educate visitors about the importance of the 1901 “Lucas Gusher.”

The “Lucas Gusher” and other nearby discoveries changed American transportation by providing abundant oil for cheap gasoline. The drilling boom would bring hope to a region devastated just a few months earlier by the Galveston Hurricane, still the deadliest in U.S. history. Petroleum production from the well’s geologic salt dome had been predicted by Patillo Higgins, a self-taught geologist and Sunday school teacher.

Learn more in Spindletop launches Modern Petroleum Industry.

January 10, 1919 – Elk Hills Oilfield discovered in California

Standard Oil of California discovered the Elk Hills field in Kern County, and the San Joaquin Valley soon ranked among the most productive oilfields in the country. It became embroiled in the 1920s Teapot Dome lease scandals and yielded its billionth barrel of oil in 1992. Visit the petroleum exhibits of the Kern County Museum in Bakersfield and at the West Kern Oil Museum in Taft.

January 10, 1921 – Oil Boom arrives in Arkansas

“Suddenly, with a deafening roar, a thick black column of gas and oil and water shot out of the well,” noted one observer in 1921 when the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well struck oil near El Dorado, Arkansas. H.L. Hunt would soon arrive from Texas (with $50 he had borrowed) and join lease traders and speculators at the Garrett Hotel — where fortunes were soon made and lost. “Union County’s dream of oil had come true,” reported the local paper. The giant Arkansas field would lead U.S. oil output in 1925 with production reaching 70 million barrels.

Learn more in First Arkansas Oil Wells.

January 11, 1926 – “Ace” Borger discovers Oil in North Texas

Thousands rushed to the Texas Panhandle seeking oil riches after the Dixon Creek Oil and Refining Company completed its Smith No. 1 well, which flowed at 10,000 barrels a day in southern Hutchinson County. A.P. “Ace” Borger of Tulsa, Oklahoma, had leased a 240-acre tract. By September, the Borger oilfield was producing more than 165,000 barrels of oil a day.

A downtown museum exhibits Borger’s oil heritage. Photo by Bruce Wells.

After establishing his Borger Townsite Company, Borger laid out streets and sold lots for the town, which grew to 15,000 residents in 90 days. When the oilfield produced large amounts of natural gas, the town named its minor league baseball team the Borger Gassers. The team left the league in 1955 (owners blamed air-conditioning and television for reducing attendance).

Dedicated in 1977, the Hutchinson County Boom Town Museum in Borger celebrates “Oil Boom Heritage” every March.

January 12, 1904 – Henry Ford sets Speed Record

Seeking to prove his cars were built better than most, Henry Ford set a world land speed record on a frozen Michigan lake. At the time his Ford Motor Company was struggling to get financial backing for its first car, the Model T. It was just four years after America’s first auto auto show.

The Ford No. 999 used an 18.8 liter inline four-cylinder engine to produce up to 100 hp. Image courtesy Henry Ford Museum.

Ford drove his No. 999 Ford Arrow across Lake St. Clair, which separates Michigan and Ontario, Canada, at a top speed of 91.37 mph. The frozen lake “played an important role in automobile testing in the early part of the century,” explained Mark DIll in “Racing on Lake St. Clair” in 2009. “Roads were atrocious and there were no speedways.”

Learn about a 1973 natural gas-powered world land speed record in Blue Flame Natural Gas Rocket Car.

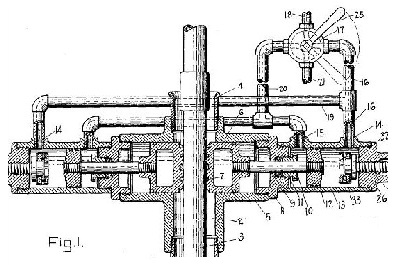

January 12, 1926 – Texans patent Ram-Type Blowout Preventer

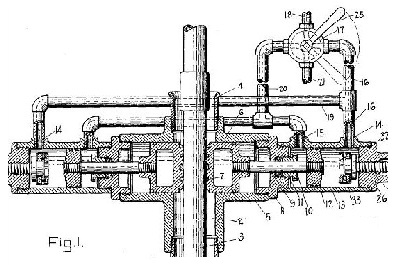

Seeking to end dangerous and wasteful oil gushers, James Abercrombie and Harry Cameron patented a hydraulic ram-type blowout preventer (BOP). About four years earlier, Abercrombie had sketched out the design on the sawdust floor of Cameron’s machine shop in Humble, Texas. Petroleum companies embraced the new technology, which would be improved in the 1930s.

James Abercrombie’s design used hydrostatic pistons to close on the drill stem. His improved blowout preventer set a new standard for safe drilling

First used during the Oklahoma City oilfield boom, the BOP helped control production of the highly pressurized Wilcox sandstone (see World-Famous “Wild Mary Sudik”). The American Society of Mechanical Engineers recognized the Cameron Ram-Type Blowout Preventer as an “Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark” in 2003.

Learn more in Ending Oil Gushers – BOP.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); Humble, Images of America (2013); Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund 1976-2011: A 35-year Michigan Oil and Gas Industry Investment Heritage in Michigan’s Public Recreation Future

(2013); Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund 1976-2011: A 35-year Michigan Oil and Gas Industry Investment Heritage in Michigan’s Public Recreation Future (2011); Handbook of Petroleum Refining Processes

(2011); Handbook of Petroleum Refining Processes (2016); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry (2016); Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

(2016); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry (2016); Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (2004); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery at Beaumont, Texas, in 1901

(2004); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery at Beaumont, Texas, in 1901 (2008); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(2008); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford

(1982); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford (2014); Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language

(2014); Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language (2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 30, 2024 | This Week in Petroleum History

December 30, 1854 – First American Oil Company incorporates –

George Bissell and six investors incorporated the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of New York. Convinced oil could be found in northwestern Pennsylvania, Bissell formed this first U.S. petroleum exploration company “to raise, manufacture, procure and sell Rock Oil” from Hibbard Farm in Venango County. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 29, 2024 | Petroleum Technology

The petroleum industry’s difficult job of retrieving broken (and expensive) equipment obstructing an oil well — “fishing” — began in 1859 when a drilling tool stuck at 134 feet deep and ruined a Pennsylvania well. The technical challenges at far greater depths have tormented exploration companies ever since.

Just four days after the August 27, 1859, first U.S. oil discovery by Edwin L. Drake at Titusville, Pennsylvania, a much less known oil and natural gas industry pioneer began America’s second well to be drilled for petroleum. John Livingston Grandin dug his well nearby using a simple spring pole — but soon wedged his iron chisel downhole.

John L. Grandin attempted to recover a lost drill bit at his 1859 well near Tidioute, Pennsylvania. Warren County roadside marker photo.

The 22-year-old Grandin improvised his own well fishing tools, but not only lost his drill bit (an industry first), he ended up with America’s first dry hole among other petroleum industry milestones.

Searching for oil was less an earth science and more an art in the exploration and production industry’s earliest days. Geologists in Pennsylvania’s “valley that changed the world” knew far more about finding coal seams than characteristics of oil-bearing formations.

Making Hole

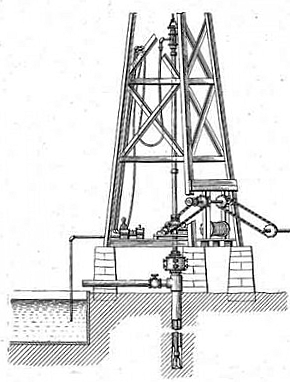

Even as drilling technologies evolved from spring poles and cable tools to modern rotary rigs, downhole problems remained — especially as wells reached new depths (learn more in Making Hole — Drilling Technology).

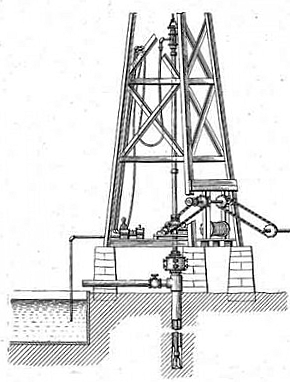

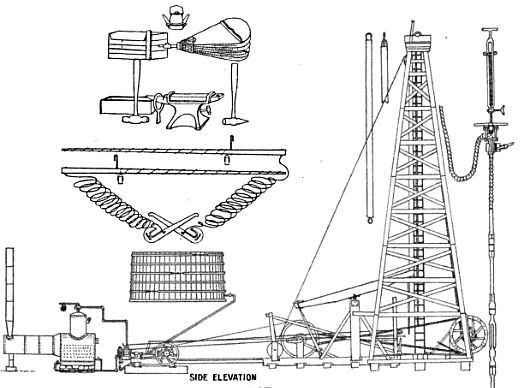

A 19th-century cable-tool rig, like its ancient predecessor the spring pole, utilized percussion drilling — the repeated lifting and dropping of a heavy chisel using hemp ropes. Drilling time and depth improved with the addition of steam power and tall, wooden derricks.

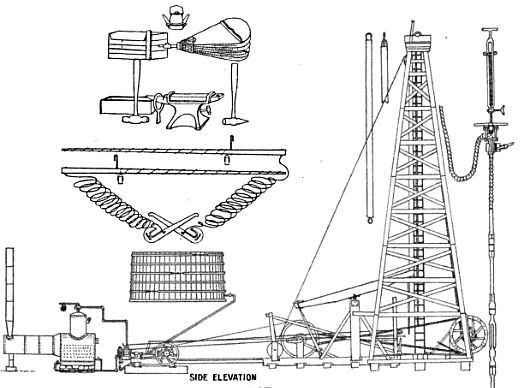

A standard, 82-foot cable-tool derrick used a steam boiler and one-cylinder engine connected to a “walking beam. Image from The Oil-Well Driller, 1905.

As depths increased, frequent stops were needed to bail out water and cuttings — and sharpen the bit’s iron edge. Small forges were often just feet from the well bore.

Despite drillers trying to avoid having expensive tools jammed deep in the well, accidents happened. The cable-tool rig’s manila rope or wire line would break. A pipe connection might bend. The downhole tool assemblies could no longer be lifted and dropped.

On the rig floor, fishing tools had to be lowered by a line into the well, armed at their end with spears, clamps and hooks. Sometimes a wood, wax and nails “impression block” was first lowered to get an idea of what lay downhole.

Hooks and Spears

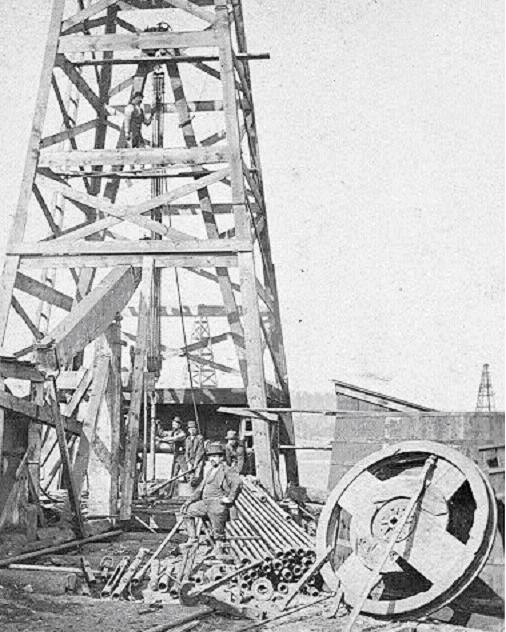

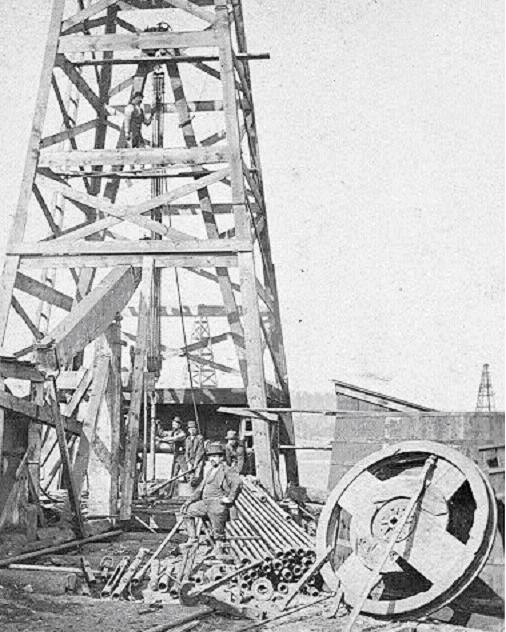

In percussion drilling, the heavy cable-tool assembly could get jammed in the borehole and could no longer be repeatedly lifted and dropped. In the foreground of the photograph below, the large wheel at right (with small, square hub) received the uppermost part of a fishing pole. A rope was wound around this wheel’s rim and led to the “bull wheel” shaft.

The term fishing came from early percussion drilling using cable tools. When the derrick’s manila rope or wire-line rope broke, a crewman lowered a hook and attempted to pull out the well’s heavy iron bit. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Among the fishing tools at the man’s feet are 3.5-inch iron poles, each 20 feet in length and weighing 500 pounds. To fish for stuck tools, these were lowered in well, armed at their end with a “die” with a left-hand thread cut in it. This die fit over the end of the stuck tool, tapered inward slightly, and when turned to the left, cut a thread on the cable tool.

The bull wheel, driven by the well’s steam-powered drilling engine, exerted a tremendous strain on the assembled poles. Since that strain was always to the left, the die gradually cut a thread in the stuck cable tool. One of the cable tool sections would eventually “yield, unscrew, and be removed.”

The operation repeated until the lowest piece was reached. A “spud” was then employed. Drilling usually would continue into the night, illuminated by two-wicked “yellow dog” lanterns.

Knives and Whipstocks

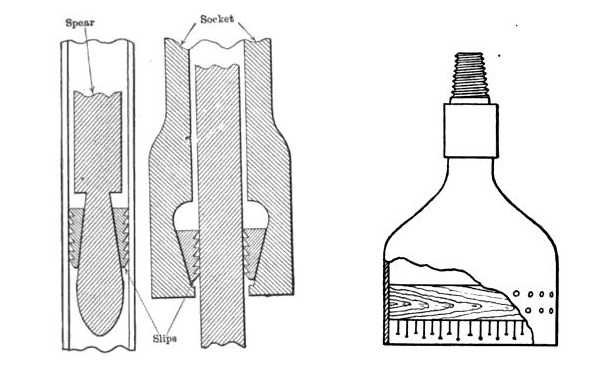

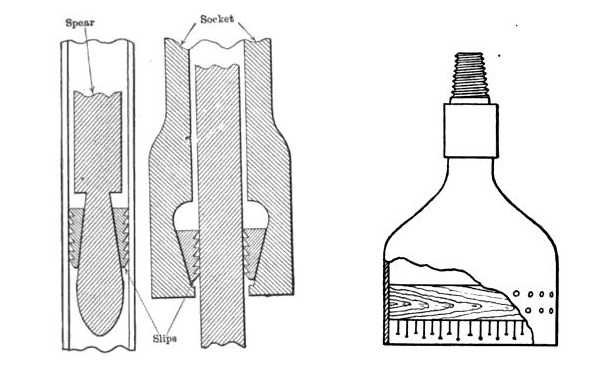

“Well fishing tools are constantly being improved and new ones introduced,” explained David T. Day in his A Handbook of the Petroleum Industry in 1922. Describing cable tool operations, he explained that the basic principle of well fishing tools often involved milled wedges — on a spear or in a cylinder — for recovering lost tubing or casing.

As drillers gained experience with deeper wells, patent applications included hundreds of designs for catching some tool or part that had been broken or lost in the borehole. Many of these “fishing tools” could be created on-site since most cable-tool rigs already had a forge for sharpening bits on the derrick floor.

Day noted that the simpler types of fishing tools comprised “horn sockets, corrugated friction sockets, rope grabs, rope spears, bit hooks, spuds, whipstocks, fluted wedges, rasps, bell sockets, rope knives, boot jacks, casing knives and die nipples.”

Basic fishing tools include the spear and socket, each with milled edges. Using nails and wax, an impression block helps determine what is stuck downhole. Image from A Handbook of the Petroleum Industry, 1922.

These and other devices, when used with an auger stem in various combinations called jars, can secure a powerful upward stroke or “jar” and thus dislodge and recover the tool being sought, Day explained in his 1922 book.

“The jars, essentially and universally used in fishing with cable tools, consist off two heavy forged-steel links, interlocking as the links of a cable chain, but fitting together more snugly,” he added.

“Many lost tools that cannot be recovered are drilled up or ‘side-tracked” (driven into or against the wall) and passed in drilling,” Day explained. Much depended upon “the skill and patience of the driller.”

Once all well fishing tools failed, a final resort was a whipstock, which allowed the bit to angle off and bypass the fish to leave the operator with a deviated hole. This was sometimes unpopular where wells were closely spaced.

By the early 1900s, rotary drilling introduced the hollow drill stem that enabled broken rock debris to be washed out of the borehole. It led to far deeper wells.

As drilling with rotary rigs became more common in the early 1900s, fishing methods adapted. “In rotary drilling, the only tools ordinarily used in the well are the drill pipe and bits,” Day noted, adding that the rotary fishing tools, “were comparatively free from the complexities of cable-tool work.”

Most rotary fishing jobs were caused by “twist offs” (broken drill pipe), although the bit, drill coupling or tool joints may break or unscrew. As in cable-tool fishing, an impression block often was needed to determine the proper fishing tool.

But even back then — and especially now with wells miles deep and often turned horizontally — when a downhole problem occurred, the well could be lost for good.

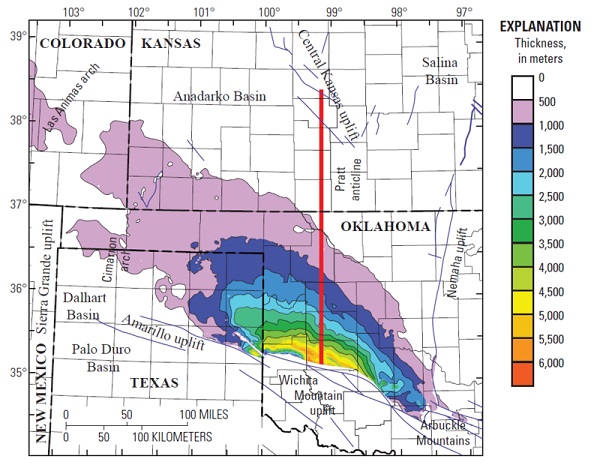

Elk City, Deep Gas Capital

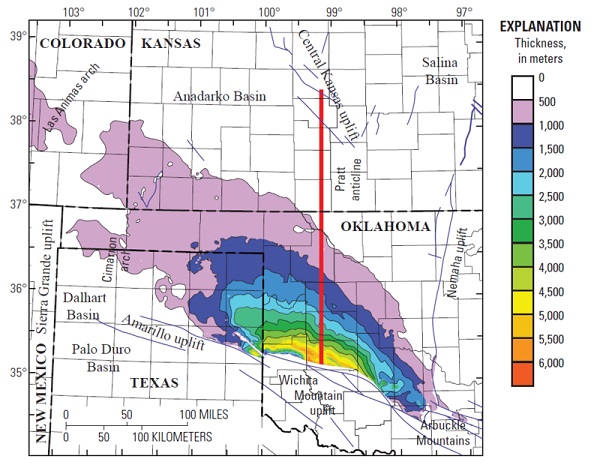

The Anadarko Basin extends across western Oklahoma into the Texas Panhandle and into southwestern Kansas and southeastern Colorado. It includes the Hugoton-Panhandle field, the Union City field and the Elk City field and is among the most prolific natural gas-producing areas in North America.

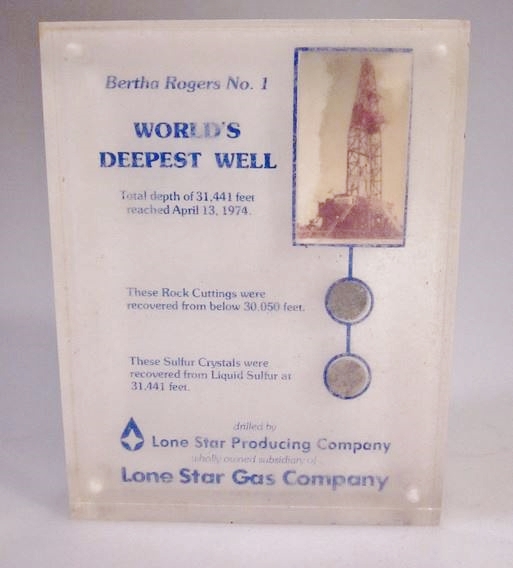

In 1980, the Oklahoma Historical Society and Oklahoma Petroleum Council dedicated a granite monument at Third and Pioneer streets in Elk City, Oklahoma. The Washita County marker notes:

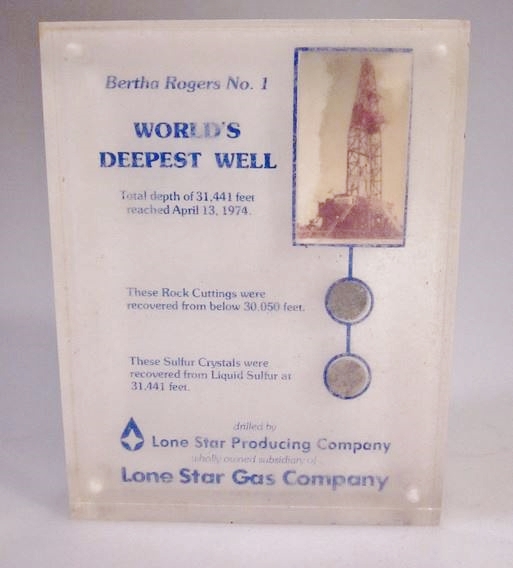

The Deep Anadarko Basin of Western Oklahoma is one of the most prolific gas provinces of North America. Wells drilled here have been among the world’s deepest. The Bertha Rogers No. 1 in Washita County, drilled in 1971 to 31,441 feet, was then the world’s deepest well. In 1979 the No. 1 Sanders well near Sayre became Oklahoma’s deepest gas producer at 24,996 feet.

When controls on gas prices were lifted, Anadarko justified the faith and perseverance of The GHK Company and other operators who pioneered in deep drilling. The shallow horizons of Greater Anadarko account for much of this nation’s proved gas reserves. Deeper sediments below 15,000 feet remain virtually unexplored. Renewed assessment of some 22,000 cubic miles of deep sediments may carry over into the 21st Century.

A 2014 geologic map of 50,000 square mile Anadarko Basin showing thickness of strata courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.

For the 20th century’s final quarter, the Basin remains the frontier of deep drilling technology centered on Elk City, “Deep Gas Capital of the World”. As gas prices equate more closely to value, the nation’s needs may be met increasingly from this massive sedimentary basin, a focal point in drilling innovation and geological interpretation.

In re-energizing America, Anadarko will not yield its gas easily or briefly. Promised rewards lying beyond the threshold of drilling techniques demand massive investment. In challenging the inventive enterprise of America’s energy industry, this Basin will remain the heartland of technology in penetrating the earth’s crust.

A 1974 souvenir of the Bertha Roger No. 1 well, which sought natural gas almost six miles deep in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin.

Until the 1960s, few companies could risk millions of dollars and push rotary rig drilling technology to reach beyond the 13,000-foot level in what geologists called “the deep gas play.”

The great expense and technological expertise necessary to complete ultra-deep natural gas wells at these depths made the Anadarko Basin “the domain of the major petroleum corporations,” explained Bobby Weaver, oil historian and frequent article contributor to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

GHK Company and partner Lone Star Producing Company believed ultra-deep wells in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin could produce massive amounts of natural gas. They began drilling wells more than three miles deep in the late 1960s.

South of Burns Flat in Washita County, their Bertha Rogers No.1 would reach almost six miles deep in 1974 — after a deep fishing trip.

Deep Fishing in Oklahoma

In March 1974 in far western Oklahoma, after 16 months of drilling and almost six miles deep, the Bertha Rogers No. 1 rotary rig drill stem sheared, leaving 4,111 feet of pipe and the drill bit stuck downhole. Spudded in November 1972 and averaging about 60 feet per day, the Bertha Rogers had been heading for the history books as the world’s deepest well at the time.

Independent producer John West in 2006 preserved artifacts in the closed Anadarko Basin Museum of Natural History in Elk City, Oklahoma. Photo by Bruce Wells.

It was March 1974 and the enormous investment of Lone Star Producing Company of Dallas, and partner GHK Company of Oklahoma City, was about to be lost. Desperate GHK executives turned to a “fishing” company in Texas.

Millions of dollars hung in the balance when Houston-based Wilson Downhole Service Company, was called and tool-fishing expert Mack Ponder sent to the rescue.

Against all odds and employing the latest 1970s technology, Ponder was able to retrieve the pipe sections and drill bit from 30,019 feet down, bringing operations back online and enabling drilling to continue even deeper into Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin, at a site about 12 miles west of Cordell.

Although the remarkable deep fishing achievement was celebrated, the Bertha Rogers No. 1 had to be completed at just 14,000 feet after striking molten sulfur at 31,441 feet. The equipment could not take the abuse at total depth. The well set a world record and remains one of the deepest ever drilled.

Completed at a depth of almost 25,000 feet, the Beckham County well would become Oklahoma’s deepest natural gas producer (also see Anadarko Basin in Depth`).

Oil Well Fishing Tool Technician

The U.S. Labor Department describes an “Oil Well Fishing Tool Technician” (Occupational Title 930.261-010) as an occupation that “analyzes conditions of unserviceable oil or gas wells and directs use of special well-fishing tools and techniques to recover lost equipment and other obstacles from boreholes of wells,”

The government description adds that the technician plans fishing methods, selects tools, and “directs drilling crew in applying weights to drill pipes, in using special tools, in applying pressure to circulating fluid (mud), and in drilling around lodged obstacles or specified earth formations, using whipstocks and other special tools.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2007); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Fishing in Petroleum Wells.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/high-flying-trademark. Last Updated: December 28, 2024. Original Published Date: June 1, 2006.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 23, 2024 | This Week in Petroleum History

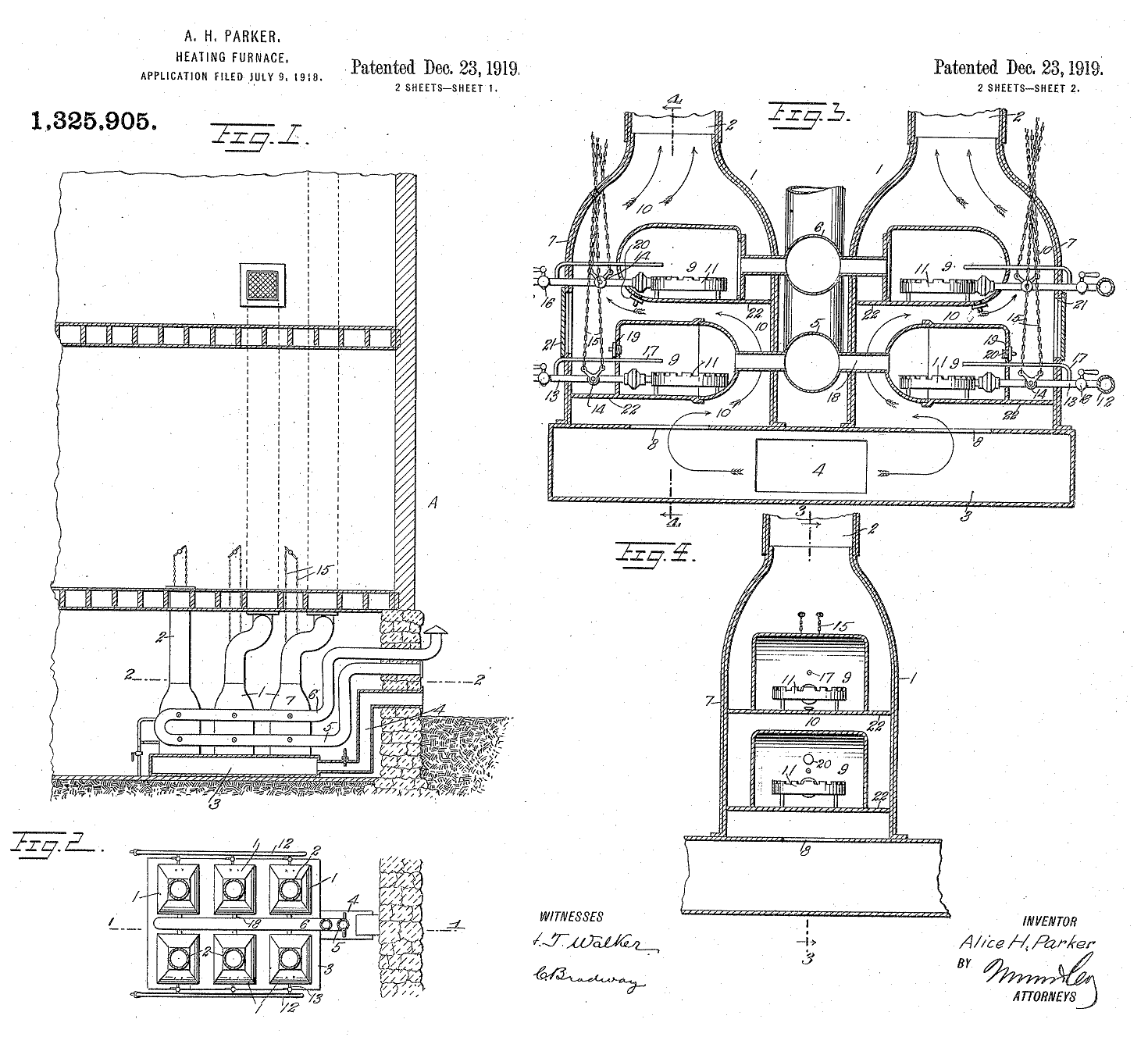

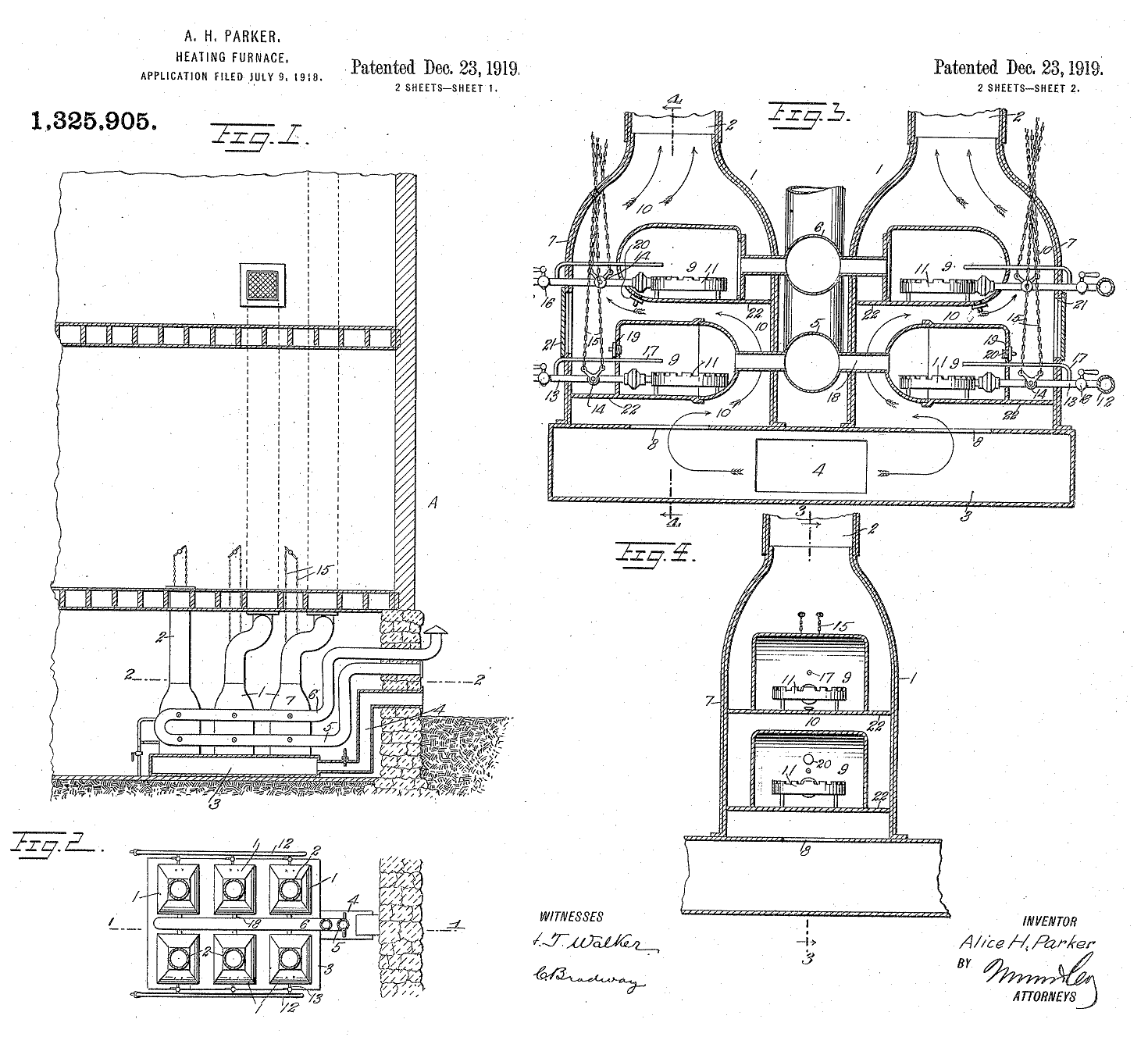

December 23, 1919 – Home Gas Heating System –

When most American homeowners were stocking up on wood and coal to heat their homes, Alice H. Parker patented a gas furnace system with adjustable ducts. The 1910 graduate of Howard University described her patent (no. 1,325,905) as a reliable gas-heating furnace, with “individual hot air ducts leading to different parts of the building, so that heating of the various rooms or floors can be regulated as required.”

Alice Parker in 1919 patented her design for a gas furnace with adjustable hot air ducts.

Although Parker’s patent was not the first for a gas furnace design, according to Heat Treat Today, “It was unique in that it incorporated a multiple yet individually controlled burner system.” By 1927, more than 250,000 U.S. homeowners were heating with natural gas.

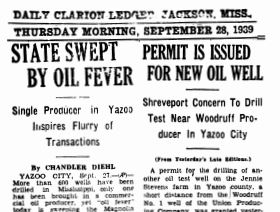

December 23, 1943 – Oilfield discovered in Mississippi

Gulf Oil Company discovered a new Mississippi oilfield at Heidelberg in Jasper County. The company’s surveyors had recognized the geological potential of the area southeast of Jackson as early as 1929, and Gulf Oil used newly developed seismography methods and core drilling technologies to look for oil-bearing formations.

Mississippi’s petroleum industry began with a 1939 oilfield discovery in Yazoo County.

The 1943 discovery well revealed one of the state’s largest oilfields since the Tinsley oil-producing formation in 1939. The first major Mississippi oil well was drilled following a geological survey by a young geologist — who had sought a suitable Yazoo County clay to mold cereal bowls for children. “It all began quite independently of any search for oil,” a historian later explained.

Learn more in the First Mississippi Ol Wells.

December 24, 1997 – Petroleum Products in a Holiday Classic

The TNT network began airing “24 Hours of A Christmas Story,” an annual marathon of an independent film made in 1983. The circa 1940 movie’s popularity — and merchandise sales — led to more marathons on TBS. In addition to the plastic leg lamp with black nylon polymer stocking, another petroleum product featured: a paraffin-based novelty candy.

“A Christmas Story” featured Ralphie, his 4th-grade classmates, and an unusual petroleum product. Photos courtesy MGM Home Entertainment.

Paraffin makes its appearance when Ralphie Parker and his fourth-grade classmates smuggle Wax Fangs into class. An older generation may recall the peculiar disintegrating flavor of Wax Lips, Wax Moustaches, and Wax Bottles. Few realize the candy started in the U.S. oil patch — as did another oilfield paraffin product, Crayola Crayons.

Learn more in the Oleaginous History of Wax Lips.

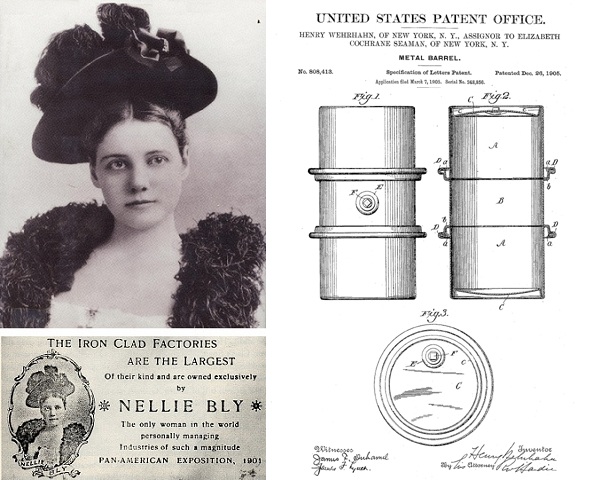

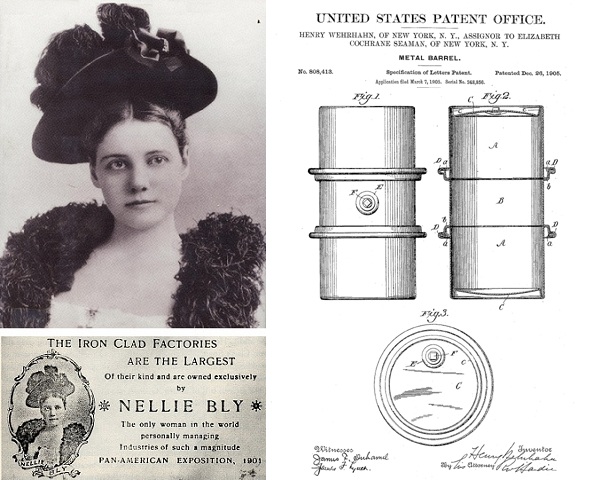

December 26, 1905 – Nellie Bly’s Ironclad 55-Gallon Metal Barrel

Inventor Henry Wehrhahn of Brooklyn, New York, received two patents that would lead to the modern 55-gallon steel drum. He assigned both to his employer, the famous journalist Nellie Bly, who was president of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company.

“My invention has for its object to provide a metal barrel which shall be simple and strong in construction and effective and durable in operation,” Wehrhahn noted. After receiving a second patent for detaching and securing a lid, he assigned them to Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman (Nellie Bly), the recent widow of the company’s founder, Robert Seaman.

Nellie Bly was assigned a 1905 patent for the “Metal Barrel” by its inventor, Henry Wehrhahn, who worked at her Iron Clad Manufacturing Company.

Well-known as a reporter for the New York World, Bly manufactured early versions of the “Metal Barrel” that would become today’s 55-gallon steel drum. Wehrhahn later became superintendent of a steel tank company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Learn more in the Remarkable Nellie Bly’s Oil Drum.

December 28, 2017 – Smithsonian features Oilfield Nitro Factory

“The True Story of Mrs. Alford’s Nitroglycerin Factory,” proclaimed an article in Smithsonian magazine about the early oil industry. “Mary Alford remains the only woman known to own a dynamite and nitroglycerin factory,” the magazine added about the 19th-century nitroglycerin factory owner. With the Bradford, Pennsylvania, oilfield in 1881 accounting for 83 percent of all U.S. oil production, Mrs. Alford was reported to be “an astute businesswoman in the midst of America’s first billion-dollar oilfield.”

Learn more in Mrs. Alford’s Nitro Factory.

December 28, 1930 – Well reveals extent of East Texas Oilfield

Three days after Christmas, a major oil discovery on the farm of the widow Lou Della Crim of Kilgore revealed the extent of the giant East Texas oilfield. Her son, J. Malcolm Crim, had ignored advice from most geologists and explored about 10 miles north of the field’s discovery well, drilled in October by Columbus “Dad” Joiner on the farm of another widow, Daisy Bradford.

“Mrs. Lou Della Crim sits on the porch of her house and contemplates the three producing wells in her front yard,” notes the caption of this undated photo courtesy Neal Campbell, Words and Pictures.

The Lou Della Crim No. 1 well erupted oil on a Sunday morning while “Mamma” Crim was attending church. The well initially produced 20,000 barrels of oil a day.

One month later and 15 miles farther north, a third wildcat well drilled by Fort Worth wildcatter W.A. “Monty” Moncrief confirmed the true size of the largest oilfield in the continental United States. The East Texas field would encompass more than 480 square miles.

Learn more in Lou Della Crim Revealed.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Oil in the Deep South: A History of the Oil Business in Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, 1859-1945 (1993); How Sweet It Is (and Was): The History of Candy (2003); Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist

(1993); How Sweet It Is (and Was): The History of Candy (2003); Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist (1994); Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017); Images of America: Around Bradford

(1994); Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017); Images of America: Around Bradford (1997); The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field

(1997); The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field (2003). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2003). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 16, 2024 | This Week in Petroleum History

December 17, 1884 – Fighting Oilfield Fires with Cannons –

“Oil fires, like battles, are fought by artillery” proclaimed an article in The Tech, a student newspaper of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “A Thunder-Storm in the Oil Country” featured the reporter’s firsthand account of the problem of lightning strikes in America’s oilfields.

Lightning strikes in the Great Plains resulted in oil tank fires — and the need to keep cannons nearby to shoot holes to drain the tanks. Photo courtesy Kansas Oil Museum. El Dorado, Kansas.

The MIT article not only reported on the fiery results of a lightning strike, but also the practice of using Civil War cannons to fight such conflagrations. Shooting a cannonball into the base of a burning tank allowed oil to drain safely into a holding pit until the fire died out. “Small cannons throwing a three-inch solid shot are kept at various stations throughout the region for this purpose,” the article noted.

Learn more in Oilfield Artillery fights Fires.

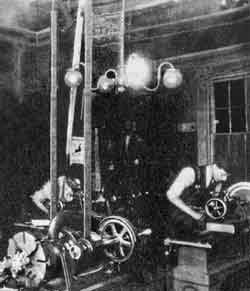

December 17, 1903 – Natural Gas contributes to Aviation History

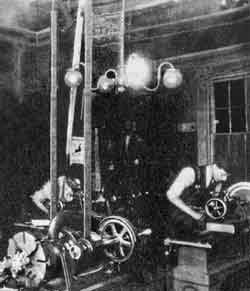

A handmade engine burning 50-octane gasoline for boat engines powered Wilbur and Orville Wright’s historic 59-second flight into aviation history at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The brothers’ “mechanician,” Charlie Taylor, fabricated the 150-pound, 13-horsepower engine in their Dayton, Ohio, workshop.

Powered by natural gas, a three-horsepower engine drove belts in the Wright workshop.

The workshop included a single-cylinder, three-horsepower natural gas-powered engine that drove an overhead shaft and belts that turned a lathe, drill press — and an early, rudimentary wind tunnel. Natural gas was piped from a field in Mercer County, about 50 miles northwest.

Learn about advances in high-octane aviation fuel in Flight of the Woolaroc.

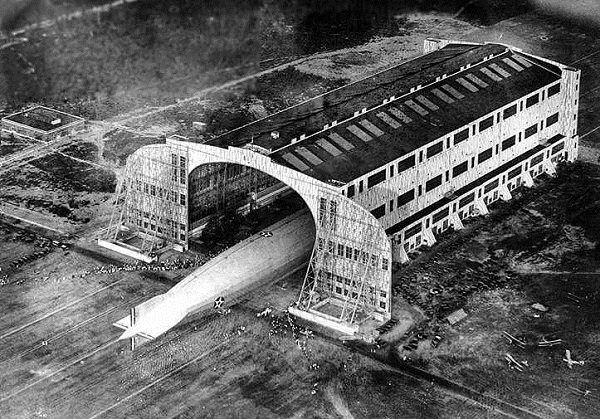

December 17, 1910 – Petrolia field brings Helium to North Texas

Although traces of oil had been found as early as 1904 in Clay County, Texas, a 1910 gusher revealed an oilfield soon named after one of the earliest boomtowns, Petrolia, Pennsylvania. The discovery well southeast of Wichita Falls produced 700 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 1,600 feet. The field’s annual oil production peaked in 1914 as discoveries at Electra and Burkburnett overshadowed Petrolia.

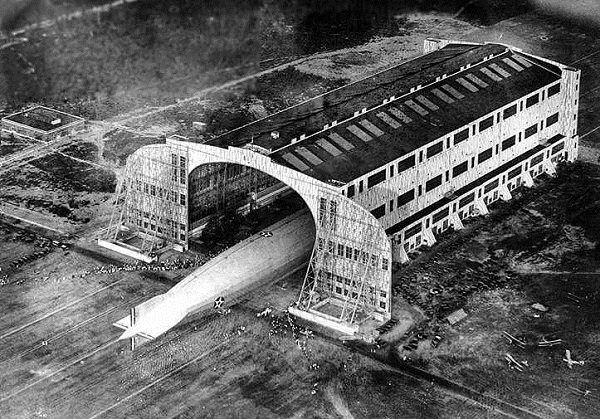

Helium derived from natural gas filled the U.S. Navy’s first helium airship, the Shenandoah, built in 1923 and here emerging from its Lakehurst, N.J., hangar.

However, the Petrolia natural gas contained .1 percent helium, a strategic resource at the time. (see Kansas “Wind Gas” Well). “In 1915 the United States Army built the first helium extraction plant in the country at Petrolia, and for several years the field was the sole source of helium for the country,” notes the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA).

December 18, 1929 – California Oil Boom in Venice

The Ohio Oil Company completed a wildcat well in Venice, California, on the Marina Peninsula, that produced 3,000 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 6,200 feet. The Ohio Oil Company, which would become Marathon Oil of Ohio, had received a zoning variance to drill within the city limits. The Venice oilfield discovery launched another California drilling boom similar to Signal Hill eight years earlier.

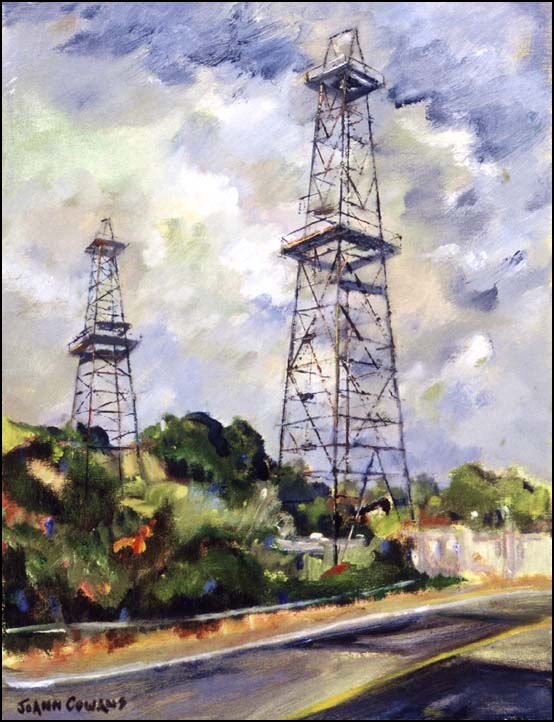

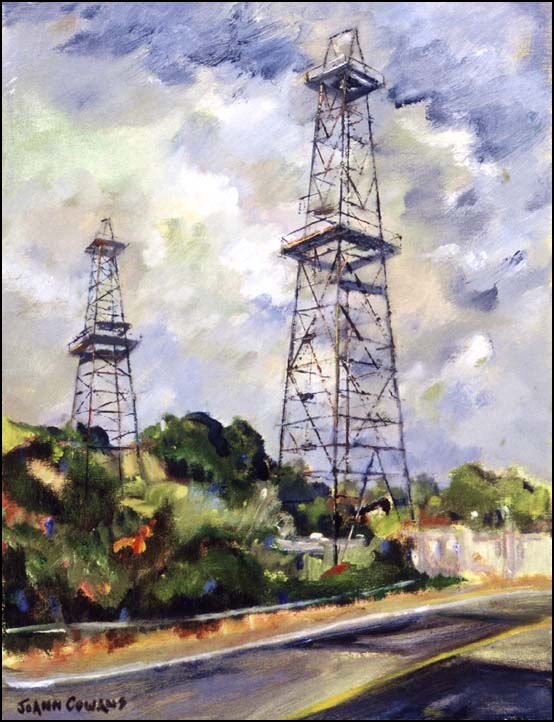

California artist JoAnn Cowans painted scenes of derricks in the Venice and Brea oilfields before they were dismantled.

“The discovery of oil at the beginning of the Depression, at a time when there was little disposable income for Venice’s amusement industry, brought the possibilities of untold wealth for the community,” notes the Vince History Site. In January 1930, a crowd of 2,000 met with city officials and demanded re-zoning to allow oil drilling.

December 18, 1934 – Hunt Oil Company founded in Texas

Hunt Oil Company, among the largest privately held U.S. petroleum companies, incorporated in Delaware and opened an office in Tyler, Texas. Four years earlier, Haroldson Lafayette “H.L.” Hunt had acquired the Daisy Bradford No. 3 well and other East Texas oilfield properties from C. Marion “Dad” Joiner.

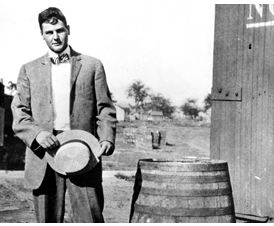

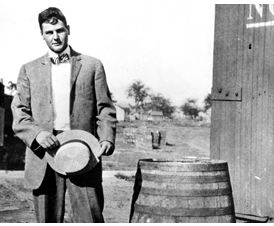

H.L. Hunt’s oil career began in Arkansas and East Texas and spanned much of the industry’s history, notes Hunt Oil Company. Photo circa 1911.

“H.L. Hunt bought the lease out ‘lock, stock and barrel,’ financing the deal with a first-of-its-kind agreement to make payments from future ‘down-the-hole’ production,” according to Hunt Energy. “The Bradford No. 3 turned out to be the discovery well of the great East Texas oilfield, which, at the time, was the greatest oilfield in the world.”

Hunt Oil moved its headquarters to Dallas in 1937 and drilled the first Alabama oil well in 1944. The company began offshore exploration in 1958 with leases in the Gulf of Mexico.

December 19, 1924 – Government debates Oil Conservation

Declaring “the supremacy of nations may be determined by the possession of available petroleum and its products,” President Calvin Coolidge appointed a Federal Oil Conservation Board to appraise oil policies and promote conservation of the strategic resource.

With Navy ships converting to oil from coal (see Petroleum and Sea Power), the resulting crude oil shortages in 1919 and 1920 gave credibility to predictions of domestic supplies running out within a decade, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Debates about oil conservation continued during establishment of President Franklin Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933 — and its rejection as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935.

December 20, 1951 – Oil discovered in Washington State

A short-lived oil discovery in Washington foretold the state’s production future. The Hawksworth Gas and Oil Development Company exploratory well was completed near Ocean City, producing 35 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 3,700 feet before being abandoned as noncommercial. In 1967, Sunshine Mining Company deepened the well to more than 4,500 feet, but with only minor shows of oil, it was shut in again.

Washington’s 1951 lone oil well yielded a total of just 12,500 barrels of oil over a decade of production.

By 2010, of the 600 exploratory wells drilled in 24 Washington counties, only one produced commercial quantities of oil — a 1959 well completed by Sunshine Mining Company 600 yards north of the failed Hawksworth site. That well, Washington’s only commercial producer, was capped in 1961.

“The geology is too broken up and it does not have the kind of sedimentary basins they have off the coast of California,” explained a Washington Natural Resources geologist in 1997 (also see California Oil Seeps).

December 21, 1842 – Birth of an Oil Town “Bird’s-Eye View” Artist

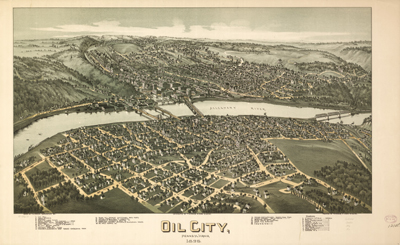

Panoramic map artist Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts. Following the fortunes of America’s early petroleum industry, he would produce hundreds of unique maps of the earliest oilfield towns of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Oklahoma and Texas.

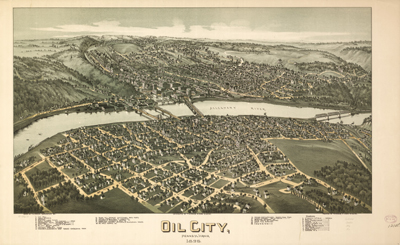

Oil City, Pennsylvania, prospered soon after America’s first commercial oil discovery in 1859 at nearby Titusville. T.M. Fowler 1896 map courtesy Library of Congress.

Fowler was one of the most prolific of the bird’s-eye view artists who crisscrossed the country during the latter three decades of the 19th century and early 20th century, according to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. Seemingly drawn from great heights, the views were made with skillful cartographic techniques.

More than 400 Thaddeus Fowler panoramas have been identified by the Library of Congress, including this detail of the booming oil town of Sistersville, West Virginia, published in 1896.

Fowler featured many of Pennsylvania’s earliest oilfield towns, including Titusville and Oil City — and the booming community of Sistersville in the new state of West Virginia. He traveled through Oklahoma and Texas in 1890 and 1891 similarly documenting Bartlesville, Tulsa, and Wichita Falls.

Learn more in Oil Town “Aero Views.”

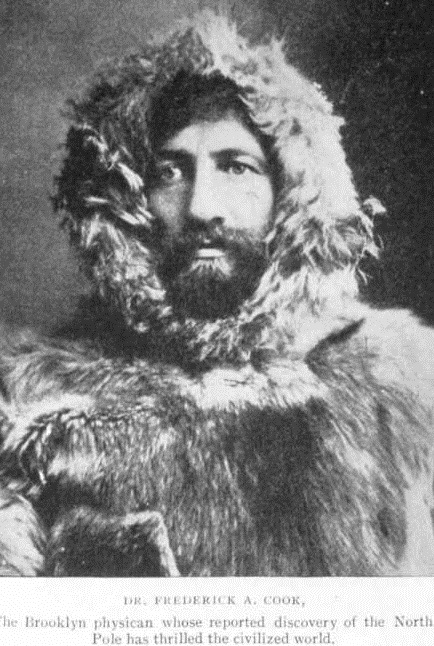

December 21, 1909 – Arctic Explorer turned Oil Promoter

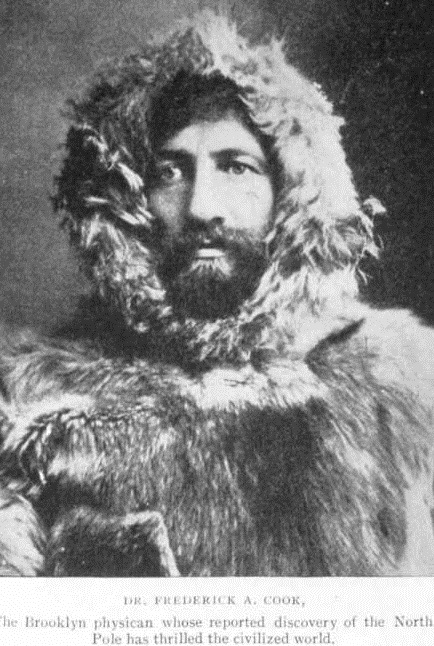

One year after making widely accepted claims to have reached the North Pole, a special commission at the University of Copenhagen ruled explorer Dr. Frederick Cook had no evidence he reached the pole during his arctic journey. Cook had already become a celebrity when Admiral Robert E. Peary achieved that milestone in April 1909.

Despite the commission’s ruling, Cook used his fame to promote fraudulent oil exploration ventures in Texas, Wyoming, Arkansas, and other states. In 1923. he was convicted of mail fraud and served prison time in Leavenworth, Kansas, until pardoned by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940.

Learn more in Arctic Explorer turned Oil Promoter.

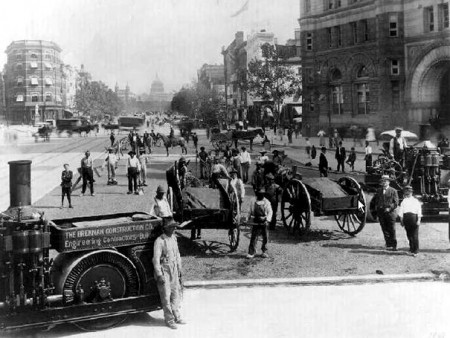

December 22, 1875 – Grant seeks Asphalt for Pennsylvania Avenue

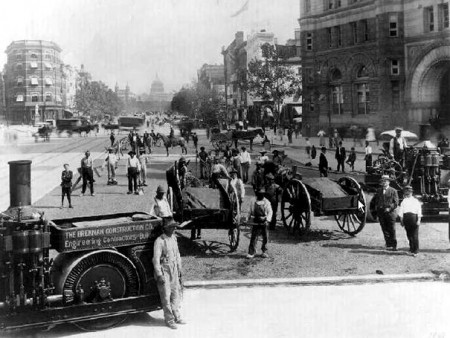

President Ulysses S. Grant convinced Congress to repave Pennsylvania Avenue’s badly deteriorated plank boards with asphalt. Grant delivered to Congress a “Report of the Commissioners Created by the Act Authorizing the Repavement of Pennsylvania Avenue.”

Pennsylvania Avenue was first paved with Trinidad bitumen in 1876. Above, asphalt distilled from petroleum in 1907 repaved the road to the Capitol.

The project would cover 54,000 square yards. “Brooms, lutes, squeegees and tampers were used in what was a highly labor-intensive process.” With work completed in the spring of 1877, the asphalt – obtained from a naturally occurring bitumen lake found on the island of Trinidad – would last more than 10 years.

In 1907, the road to the Capitol was repaved again with a superior asphalt made with petroleum from U.S. oilfields. By 2005, the Federal Highway Administration reported that more than 2.6 million miles of America’s roads were paved.

Learn more in Asphalt Paves the Way.

December 22, 1903 – Carl Baker patents Cable-Tool Bit

Reuben Carlton “Carl” Baker of Coalinga, California, patented an innovative cable-tool drill bit in 1903 after founding the Coalinga Oil Company.

“While drilling around Coalinga, Baker encountered hard rock layers that made it difficult to get casing down a freshly drilled hole,” noted a Baker-Hughes historian in 2007. “To solve the problem, he developed an offset bit for cable-tool drilling that enabled him to drill a hole larger than the casing.”

Baker Tools Company founder R.C. “Carl” Baker in 1919.

Coalinga would become a petroleum boom town thanks to Baker’s leadership, according to the town’s museum. He helped establish several oil companies, a bank, and the local power company. After drilling wells in the Kern River oilfield, he added another innovation in 1907 by patenting the Baker Casing Shoe, a device ensuring uninterrupted flow of oil through the well.

By 1913 Baker organized the Baker Casing Shoe Company (renamed Baker Tools two years later). He opened his first manufacturing plant in Coalinga in a building — today home to the R.C. Baker Museum. Baker never advanced beyond the third grade, but “possessed an incredible understanding of mechanical and hydraulic systems.”

Learn more in Carl Baker and Howard Hughes.

December 22, 1975 – Strategic Petroleum Reserve established

President Gerald R. Ford established the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve by signing the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975. With a capacity of 713.5 million barrels of oil in 2018, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve was the largest stockpile of government-owned emergency oil in the world. SPR storage sites include five salt domes on the Gulf Coast. In addition to SPR, the Department of Energy maintains a Northeast Home Heating Oil Reserve of one million barrels and a one million barrel supply of gasoline.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); The Wright Brothers (2016); Helium: Its Creation, Discovery, History, Production, Properties and Uses (2022); Black Gold, the Artwork of JoAnn Cowans

(2016); Helium: Its Creation, Discovery, History, Production, Properties and Uses (2022); Black Gold, the Artwork of JoAnn Cowans (2009); The Three Families of H. L. Hunt: The True Story of the Three Wives, Fifteen Children, Countless Millions, and Troubled Legacy of the Richest Man in America

(2009); The Three Families of H. L. Hunt: The True Story of the Three Wives, Fifteen Children, Countless Millions, and Troubled Legacy of the Richest Man in America (1989); Bird’s Eye Views: Historic Lithographs of North American Cities

(1989); Bird’s Eye Views: Historic Lithographs of North American Cities (1998); Down the Asphalt Path: The Automobile and the American City

(1998); Down the Asphalt Path: The Automobile and the American City (1994); History of Oil Well Drilling

(1994); History of Oil Well Drilling (2007). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2007). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

oilfield was discovered in Pennsylvania with the United States Petroleum Company’s well reportedly located using a witch-hazel dowser. The discovery well, which initially produced 250 barrels of oil a day, brought a “black gold” rush as boom town Pithole made headlines five years after the first U.S. oil well drilled at nearby Titusville.

in 2011.

(2013); Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund 1976-2011: A 35-year Michigan Oil and Gas Industry Investment Heritage in Michigan’s Public Recreation Future

(2011); Handbook of Petroleum Refining Processes

(2016); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry (2016); Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

(2004); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery at Beaumont, Texas, in 1901

(2008); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1982); I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford

(2014); Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language

(2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.