THUMS – California’s Hidden Oil Islands

Wells on manmade islands save “America’s Sinking City.”

Reversing an earlier ban, voters in Long Beach, California, in 1962 approved petroleum exploration in their harbor. Five major oil companies formed a company called THUMS and built four artificial islands to produce the oil.

California’s headline-making 1921 oil discovery at Signal Hill launched a drilling boom that transformed the quiet residential area. So many derricks sprouted it became known as “Porcupine Hill.”

Island Grissom, one of the four THUMS islands at Long Beach, California, was named after NASA astronaut Col. Virgil “Gus” Grissom, who died in 1967 in the Apollo spacecraft fire. Photo courtesy U.S. Department of Energy.

With many homeowners aspiring to become drillers and oilfield speculators, much of Signal Hill’s land was sold and subdivided in real estate lots of a size described as “big enough to raise chickens.”

Derricks were so close to one cemetery that graves “generated royalty checks to next-of-kin when oil was drawn from beneath family plots,” noted one historian. Neighboring Long Beach joined the drilling boom.

By 1923, oil production reached more than one-quarter million barrels of oil per day. When Long Beach instituted a per-barrel oil tax, Signal Hill residents voted to incorporate in 1924.

At the time, “the law of capture” for petroleum production ensured the formerly scenic landscape would be transformed. Competing exploration and production companies crowded around newly completed wells and chased any signs of oil to the Pacific Ocean.

The islands are among the most innovative oilfield designs in the world. Circa 1965 illustration courtesy Oxy Petroleum.

By the early 1930s, the massive Wilmington oilfield extended through Long Beach as reservoir management concerns remained in the future. Naturally produced California oil seeps had led to many discoveries south of the 1892 Los Angeles City field.

Onshore and offshore tax revenues generated by production of more than one billion barrels of oil and one trillion cubic feet of natural gas helped underwrite much of the Los Angeles area’s economic growth. But not without consequences.

Long Beach: A Sinking City

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reported, “Subsidence, the sinking of the ground surface, is typically caused by extracting fluids from the subsurface.”

Petroleum reserves brought drilling booms to southern California. By 1923, oil production reached more than one-quarter million barrels of oil per day from Signal Hill, seen in the distance in this detail from a panorama from the Library of Congress.

Californians had a lot of experience dealing with groundwater induced subsidence and the building damage it caused, but by 1951, Long Beach was sinking at the alarming rate of about two feet each year.

Earth scientists noted that between 1928 and 1965, the community sank almost 30 feet. TIME magazine call the bustling port “America’s Sinking City.”

After decades of prospering from petroleum production, the city prohibited “offshore area” drilling to slow the subsidence as the community looked for a solution.

On February 27, 1962, Long Beach voters approved “controlled exploration and exploitation of the oil and gas reserves” underlying their harbor. The city’s charter had prohibited such drilling since a 1956 referendum. Advancements in oilfield technologies enabled Long Beach to stay afloat.

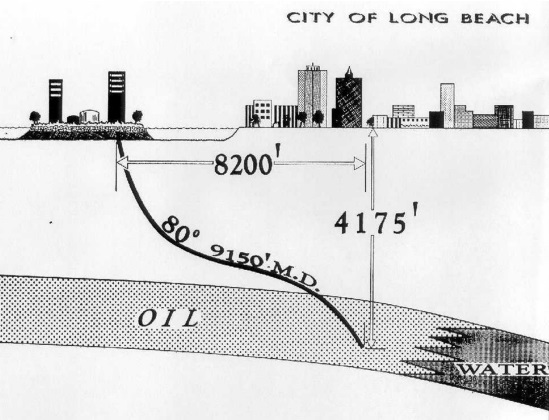

Directional drilling and water injection opened another 6,500 acres of the Wilmington field — and saved the sinking city.

THUMS: Texaco, Humble, Union, Mobil and Shell

Five oil companies formed a Long Beach company called THUMS: Texaco (now Chevron), Humble (now ExxonMobil), Union Oil (now Chevron), Mobil (now ExxonMobil) and Shell Oil Company. They built four artificial islands at a cost of $22 million in 1965 (more than $200 in 2024 dollars).

The islands — named in 1967 Grissom, White, Chaffee, and Freemen in honor of lost NASA astronauts would include 42 acres for about 1,000 active wells producing 46,000 barrels of oil and 9 million cubic feet of natural gas a day.

The prospering but “sinking city” of Long Beach would solve its subsidence problem with four islands and advanced drilling and production technologies. Photo by Roger Coar, 1959, courtesy Long Beach Historical Society.

To counter subsidence, five 1,750-horsepower motors on White Island drive water injection pumps to offset extracted petroleum, sustain reservoir pressures, and extend oil recovery. The challenge was once described as “a massive Rubik’s Cube of oil pockets, fault blocks, fluid pressures and piping systems.”

Meanwhile, all of this happens amidst the scenic boating and tourist waters in Long Beach Harbor.

The California Resources Corporation operates the offshore part on the islands of the Wilmington field, the fourth-largest U.S. oilfield, according to the Los Angeles Association of Professional Landmen, whose members toured the facilities in November 2017.

Producing in Plain Sight

“Most interestingly, the islands were designed to blend in with the surrounding coastal environment,” explained LAAPL Education Chair Blake W.E. Barton of Signal Hill Petroleum. “The drilling rigs and other above-ground equipment are camouflaged and sound-proofed with faux skyscraper skins and waterfalls.”

Most people simply do not realize the islands are petroleum production facilities. From the shore, the man-made islands appear occupied by upscale condos and lush vegetation. Many of the creative disguises came courtesy of Joseph Linesch, a pioneering designer who helped landscape Disneyland.

The THUMs islands required exceptional designs, and “the people who were involved at the time were very creative visionaries,” said Frank Komin, executive vice president for southern operations of the California Resources Corporation (CRC), owner of the islands.

About 80 percent of the company’s properties would overlie the Wilmington oilfield, according to CRC, noting that from 2003 to 2018, CRC operations generated over $5.2 billion in revenues, taxes and fees for the City of Long Beach and the state.

THUMS Island White, named for Col. Edward White II, the first American to walk in space, who died in 1967 along with NASA astronauts “Gus” Grissom and Roger B. Chaffee. A fourth island was named for NASA test pilot Ted Freeman, who in 1963 was the first fatality among the astronauts. Photo courtesy UCLA Library.

“Even today, those islands are viewed as one of the most innovative oil field designs in the world,” CRC executive Komin declared in a 2015 Long Beach Business Journal article. “The islands have grown to become icons in which the City of Long Beach takes a great deal of pride.”

The Journal explained that 640,000 tons of boulders, some as large as five tons, were mined and placed to build up the perimeters of the islands. “Concrete facades constructed for aesthetic purposes also divert industrial noise away from nearby residents,” the article added. For more noise abatement, electricity has provided nearly all the power for the islands.

The THUMS aesthetic integration of 175-foot derricks and production structures has been described by the Los Angeles Times as, “part Disney, part Jetsons, part Swiss Family Robinson.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: An Ocean of Oil: A Century of Political Struggle over Petroleum Off the California Coast (1998); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry (2016); Early California Oil: A Photographic History, 1865-1940

(1985). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “THUMS – California’s Hidden Oil Islands.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/thums-california-hidden-oil-islands. Last Updated: February 25, 2025. Original Published Date: March 8, 2018.