by Bruce Wells | Jan 5, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Giant Texas oilfield discovery in 1901 coincided with gasoline demand for automobiles.

On January 10, 1901, the “Lucas Gusher” on a small hill in Texas revealed the Spindletop oilfield, which would produce more oil in a single day than the rest of the world’s oilfields combined.

Although the 1899 Galveston hurricane (still the deadliest hurricane in U.S. history) brought great misery to southeastern Texas as the 20th century dawned, a giant oilfield discovery three miles south of Beaumont launched the modern oil and natural gas industry. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 11, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

Texas Oil boom brings shady searchers for petroleum riches.

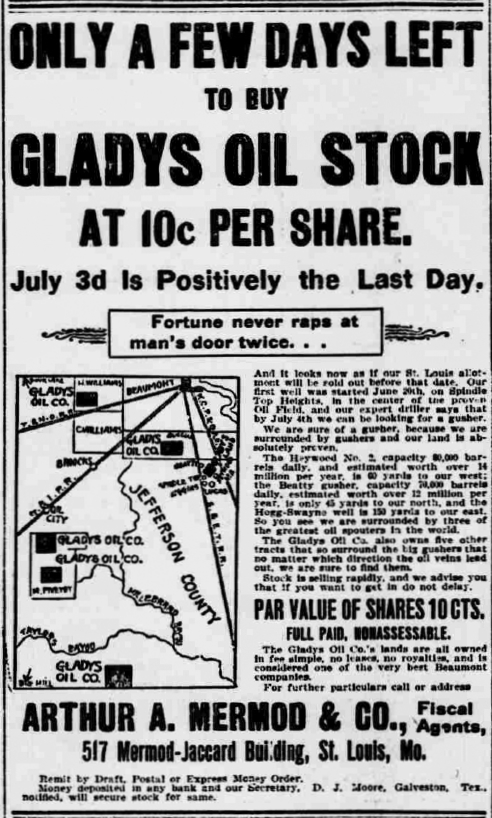

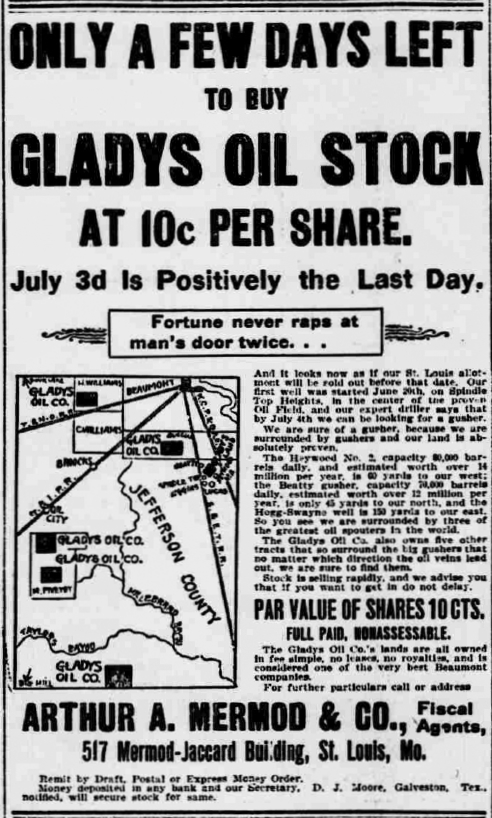

It was the greatest petroleum exploration and production since the birth of the U.S. oil industry in 1859. Hundreds of new companies formed in the wake of the spectacular 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill near Beaumont, Texas. Few had experience in the highly competitive and risky business of exploring for oil.

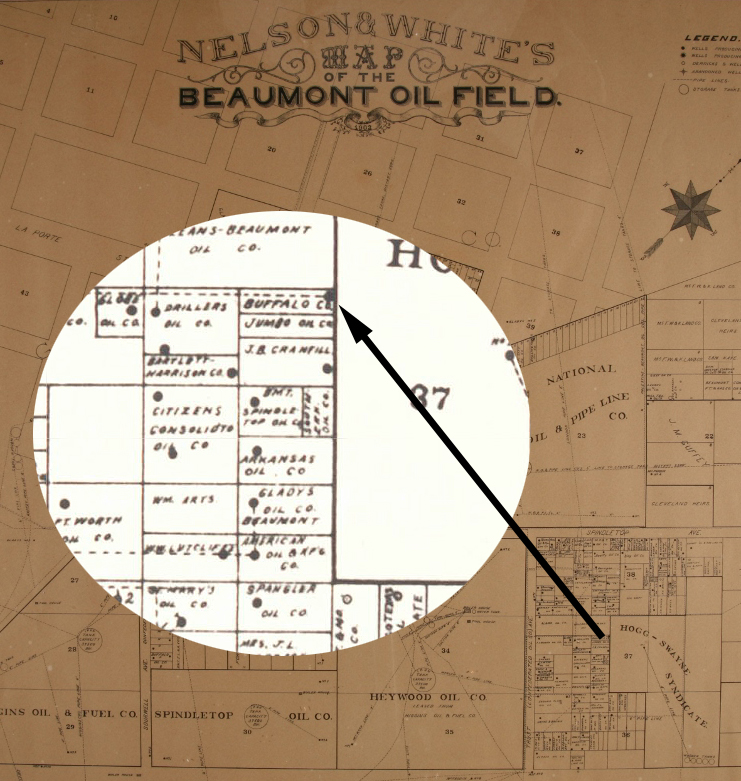

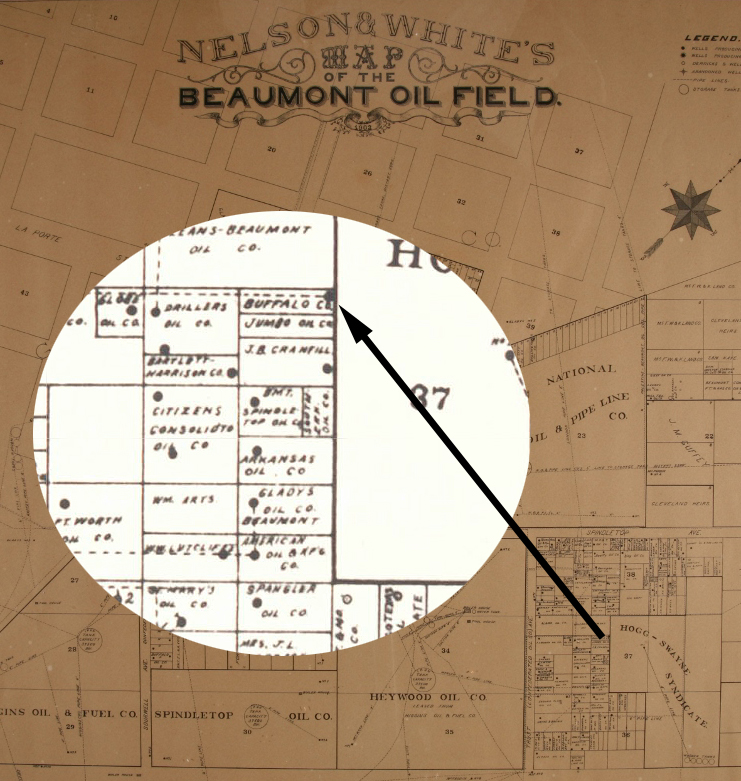

Among those ready to make fortunes for investors were two new “Gladys Oil” companies. One was from Beaumont, the other from Galveston. Contemporary maps show the Gladys Oil Company of Beaumont to have drilled a successful well very close to the famous January 10, 1901, “Lucas Gusher” well at Spindletop Hill that launched the modern U.S. petroleum industry.

Also in 1901, after 29 days of drilling in block 37, the company reported production from “Gusher No. 67” at a depth of 1,025 feet. Locating the “black gold” did not necessarily promise success.

“Swindletop”

By 1903 the Texas Secretary of State reported that Gladys Oil Company of Beaumont had “forfeited its right to do business in the state of Texas” due to a failure to pay franchise taxes. In a scenario that would repeat itself in other oilfields in coming decades, production from the giant field soon brought a collapse in oil prices.

By January 1902, stocks of both Gladys Oil companies were trading for less than 10 cents a share. The company was sued, lost, and United States Investor magazine reported it to be worthless two years later. Meanwhile, because some cash-strapped and desperate companies made questionable claims, newspapers began referring to the historic 1901 discovery as “Swindletop.”

In 1907, Success Magazine named the company in its “Fools and their Money” expose of fraudulent promotion schemes perpetrated by the New York, Chicago, and Beaumont Security Oil Trust. The Gladys Oil Company of Galveston lasted a little longer than its Beaumont twin, but not without controversy.

The trust had proclaimed, “it was impossible to lose” with an investment Gladys Oil Company of Galveston. In 1911 R.M. Smythe’s, Obsolete American Securities and Corporations, reported the stock to be worthless. Read about Pattillo Higgins, the man behind the great Spindletop discovery — and his Gladys City Oil, Gas & Manufacturing Company — see Prophet of Spindletop.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS supporter and help maintain this website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Gladys Oil Company — Oil Shale Pioneer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/gladys-oil-company. Last Updated: December 4, 2024. Original Published Date: September 11, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 24, 2023 | Petroleum Companies

New companies rush to drill at Spindletop Hill in early 1900s.

When a geyser of oil erupted in 1901 on Spindletop Hill, near Beaumont, Texas, it launched the greatest oil boom in America — far exceeding the nation’s first commercial oil well in 1859.

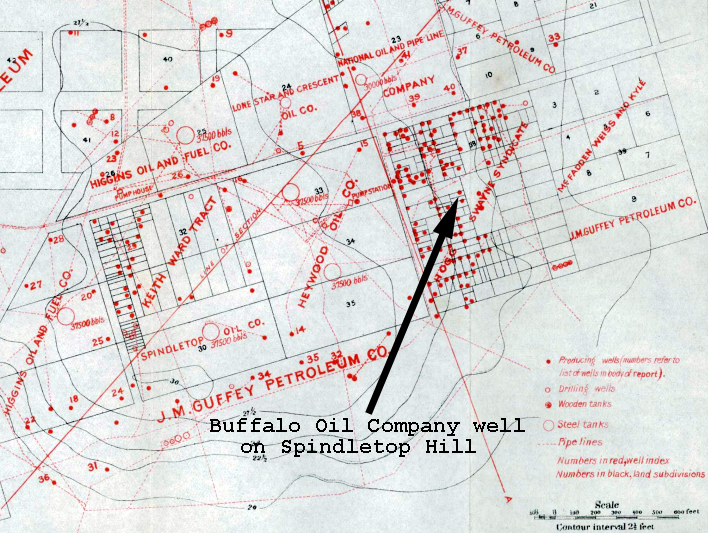

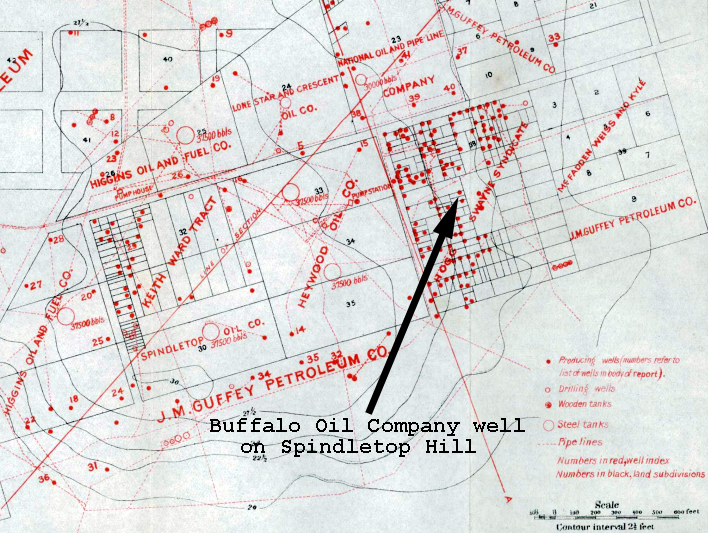

Many new and inexperienced oil ventures were formed almost overnight, including Buffalo Oil Company. The Spindletop field produced 43 million barrels of oil in its first four years, helping to launch the modern petroleum industry.

Among the 280 wells at Spindletop in 1902, Buffalo Oil completed a producing oil well at a depth of 960 feet on a lease of only 1/32 of an acre.

Buffalo Oil Company had quickly formed with $300,000 capitalization and stock listed with par value of 10 cents. Encouraged by the first well’s success, speculators invested in the company’s second. But by May 1902 the second Buffalo Oil well was “dry and abandoned” after reaching 1,400 feet deep.

As at least one expert noted at the time, the average life of flowing wells was short, “frequently but a few weeks and rarely more than a few months, with constantly diminishing output.”

Meanwhile, competing companies drove up the cost of drilling equipment and leases. Spindletop Hill was crowded with wooden derricks, oil storage tanks, and roughnecks.

Batson Oiflield

With signs of Spindletop production dropping, Buffalo Oil shifted operations to nearby Batson, where a 1903 well drilled by W.L. Douglas’ Paraffine Oil Company produced 600 barrels of oil a day from a depth of 790 feet. But the exploration company’s luck did not improve.

Map with detail showing Buffalo Oil Company lease among other drilling companies at Beaumont, Texas, home of a giant oilfield discovered in 1901.

As the Batson field reached its peak monthly production of 2.6 million barrels of oil, a fire swept through the crowded oilfield.

“The fire burned furiously for several hours and though there were no fire appliances on the field, it is doubtless if equipment could have been used owing to the intense heat generated by the flames,” noted the Petroleum Review and Mining News.

Buffalo Oil Company’s well, derrick and equipment were completely destroyed.

Often caused by lightening strikes, oil tank fires were sometimes fought using cannons (learn more in Oilfield Artillery fights Fires). After the Batson fire, the annual Buffalo Oil Company stockholder’s meeting took place in April 1904.

Fire engulfed the Batson oilfield in 1902, destroying the equipment and future of Buffalo Oil Company. Photo courtesy Traces of Texas.

“The company states that their recent investment at Batson so far has proved a serious loss to them, and the present outlook is very unfavorable,” reported the Petroleum Review and Mining News. But it got even worse.

Two weeks after the dire report to share owners, a second Batson fire destroyed another Buffalo Oil producing well and two 1,200-barrel storage tanks. Petroleum Review and Mining News concluded the fire “probably originated through an explosion in the pumping plant.”

The Batson oilfield would continue to produce for many years, but without Buffalo Oil Company. As late as 1993 the field yielded almost 200 barrels of oil a day, but Buffalo Oil was history without having paid a dividend.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Buffalo Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/buffalo-oil-company. Last Updated: October 31, 2023. Original Published Date: October 28, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Jul 21, 2016 | Energy Education Resources

The importance of preserving petroleum history, one story at a time.

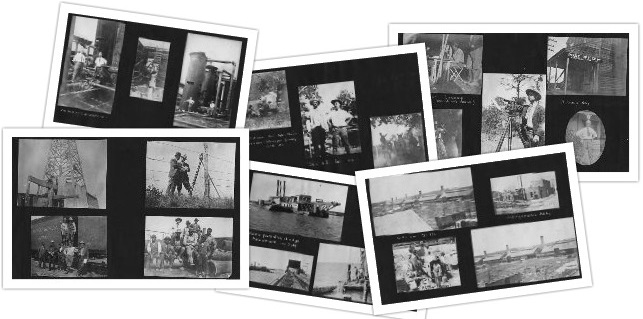

Millions of Americans have worked in the petroleum industry and many have left family records and photographs of their “oil patch” careers. The AOGHS American Oil & Gas Families project and museums listing offer help in locating suitable homes for preserving the histories of America’s oil families.

Adding Family Petroleum Heritage to Museum Collections

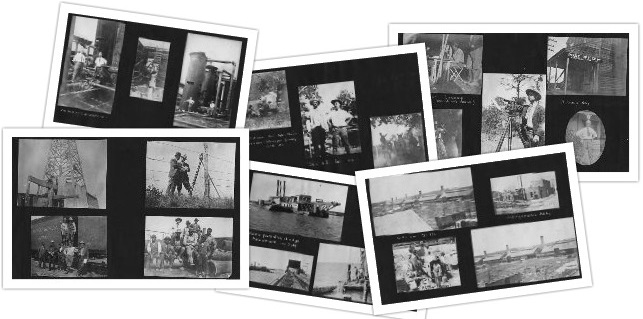

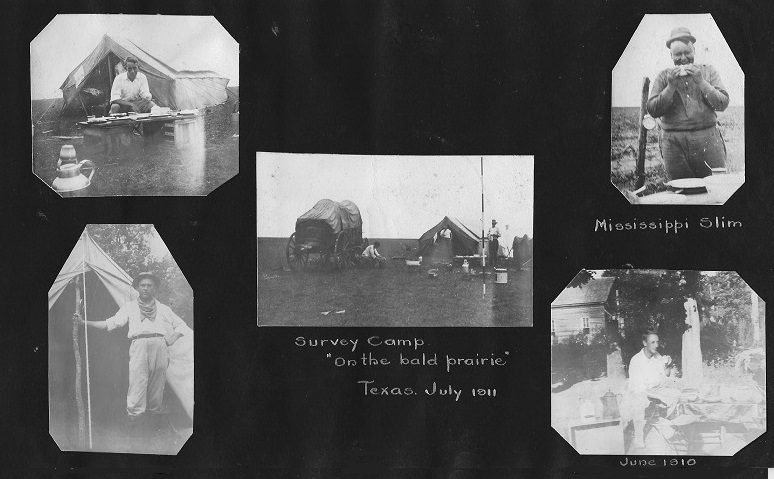

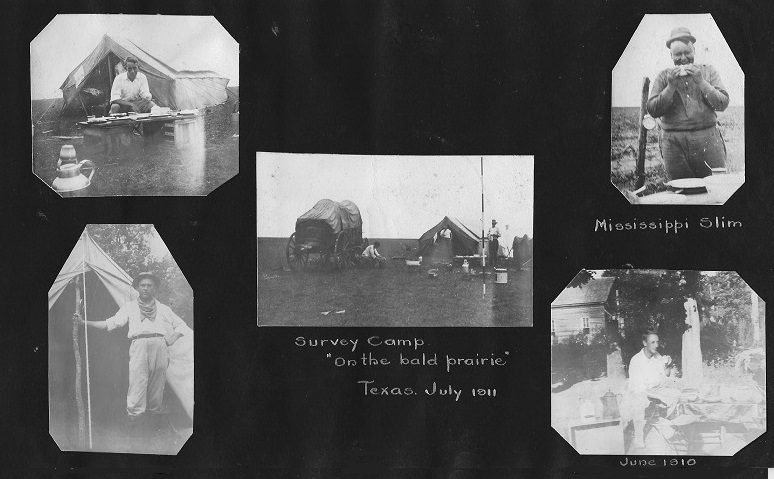

Albert Jeffreys in Texas, Louisiana, Romania, Pennsylvania and England, 1904-1913. Family photography preserved by his granddaughter, Sheila Morshead.

Finding the Right Oil and Gas Museum

In 2016, California resident Sheila Morshead contacted the American Oil & Gas Historical Society about preserving her family’s photo albums — a significant photo collection of petroleum-related images documenting her grandfather’s early 20th century career.

After finishing scanning circa 1910 images, Sheila said she hoped to find a good home for preserving her increasingly fragile originals. Many of her grandfather’s images came from the Beaumont, Texas, region (with others from Louisiana and as far away as England and Romania). She hoped someone would want to preserve the original album pages.

Thanks to Troy Gray, director of the Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum at Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas, Sheila accomplished her preservation mission.

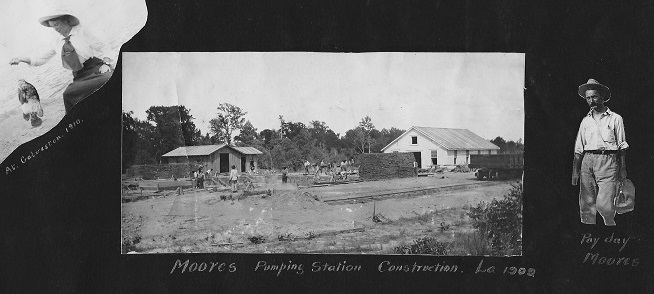

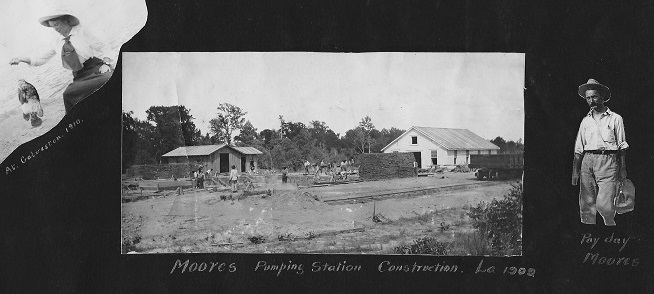

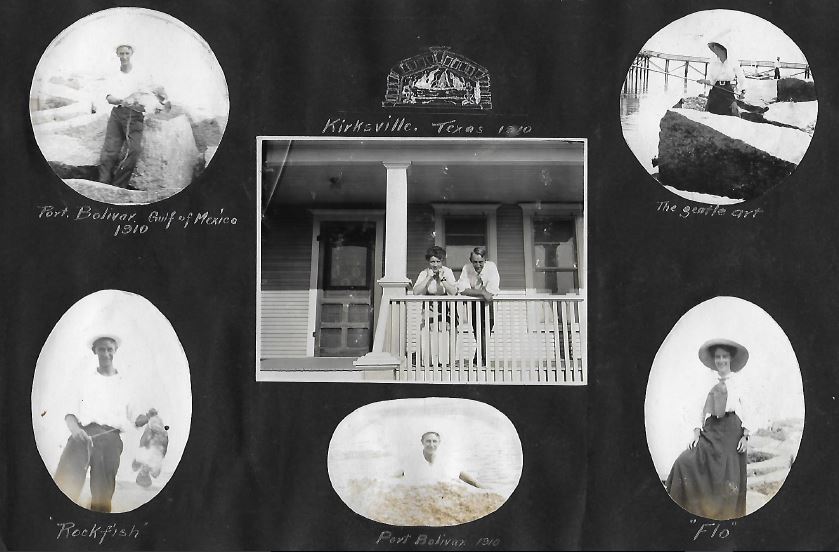

Some of Sheila’s photos depict early refineries at Beaumont. Others show oil terminals in Galveston Bay, a 1909 pumping station under construction near Moores, Louisiana, and even the apparently good fishing at Port Bolivar in the Gulf of Mexico (a few examples out of more than 120 pages are below).

One of the more than 120 family album pages of the petroleum-related career of Albert Jeffreys to be part of the permanent collection of the Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum thanks to his granddaughter.

One page from the album depicts photos from a survey camp with tents and an equipment wagon on “the bald prairie” of Texas in July 1911. It includes a photo of “Mississippi Slim,” her grandfather’s co-worker.

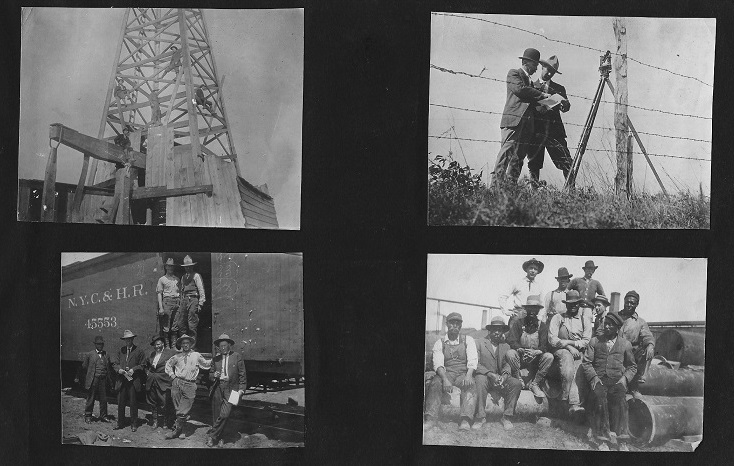

Sheila Morshead continues to research details about her grandfather’s career. She believes this is a 1912 photo of Albert Jeffreys with his surveying tripod.

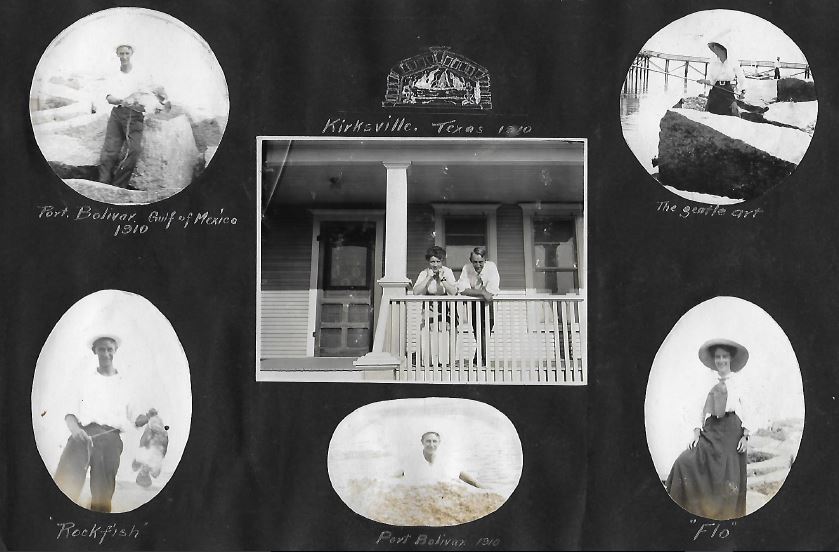

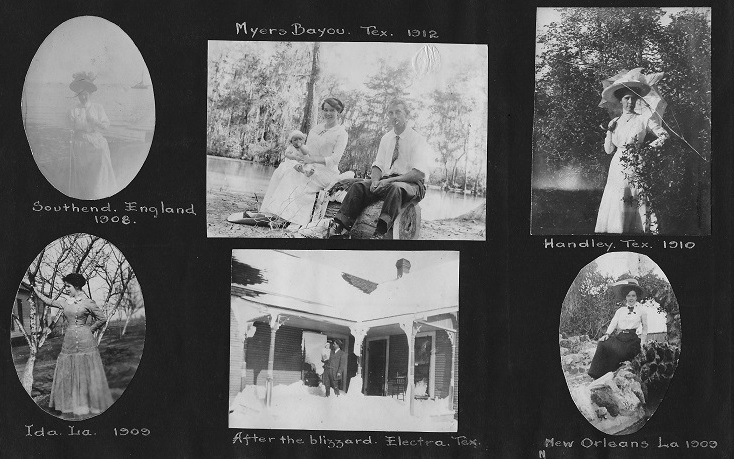

“My Grandfather was Albert Jeffreys from Great Britain,” Sheila explains about the family images, adding that Albert “Jeff” Jeffreys first arrived in the United States in 1908. The next year he got married in Shreveport, Louisiana. Albert’s wife Florence – “Flo” – also was from Great Britain, Sheila adds. “Their daughter Dorothy Kathleen Jeffreys – my mother – was born in Fort Worth, Texas, in January 1912.”

After a few busy years in Texas, Albert’s oil patch career took him to the Caucasus region of southwestern Russia in 1914. “He was sent there by the British government to work in the oilfields for his service to the country during World War I,” explains Sheila, who studied early chapters of Dan Yergin’s The Prize, to learn petroleum industry history.

“Albert eventually escaped during the Bolshevik revolution by way of Norway and returned to England,” adds his granddaughter. “I am trying to decipher the many stamps on his old passport. Needless to say, I am getting pleasantly lost in looking up British oil companies.”

After talking with Troy about his museum’s collections at the Lamar University, she removed a few original images to keep for siblings. She plans on donating all the rest as she continues to research dates and other family documents.

Albert Jeffreys Family Collection

“Here are some annotations about the scanned pictures,” Shelia noted when she emailed AOGHS seeking help in locating an appropriate oil museum or library to preserve them. “There are lots more pictures, and I can do more exact research on dates, but as you can see most have locations written on them and some dates.”

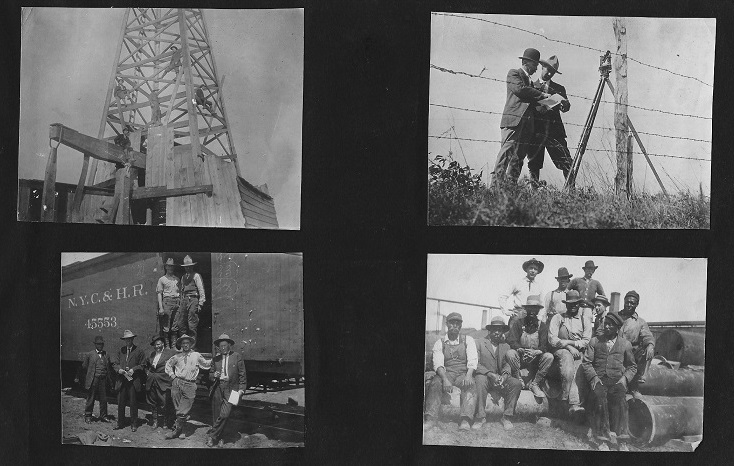

The family album includes a cable-tool oil well (with walking beam). Next to it is a photo of two unidentified men with surveying equipment. A third photo shows men standing in front of a New York Central and Hudson River Railroad car; another depicts a pipeline laying work crew.

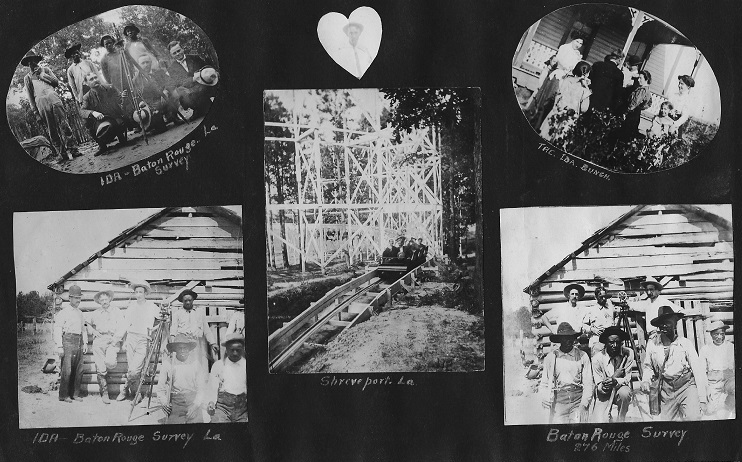

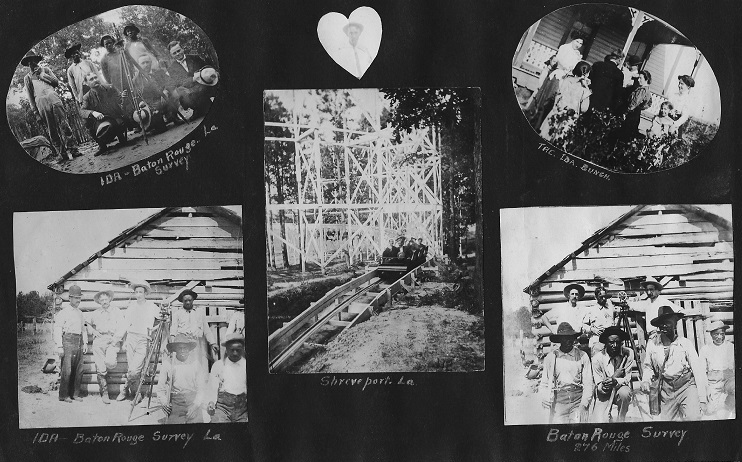

Undated images from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, include Albert Jeffreys (in heart) and his surveying co-workers along with an “Ida Bunch” family photo and riding a roller coaster in Shreveport.

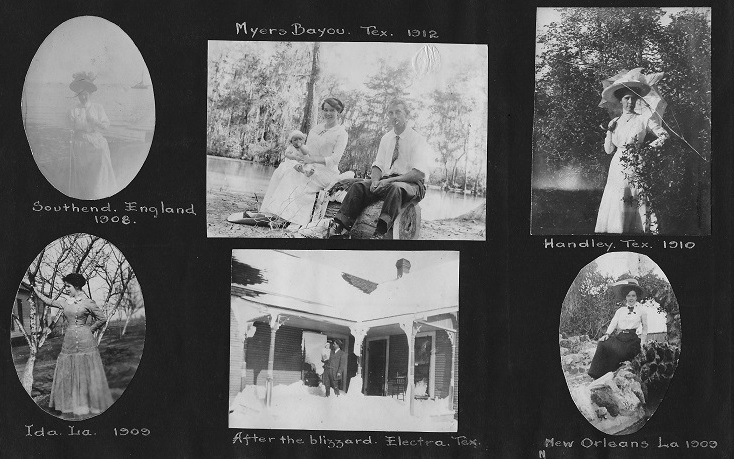

After returning from England to Louisiana oilfields in 1909, the family made stops in Handley and Electra, Texas, which included a rare blizzard, before moving on to New Orleans.

Three of Albert Jeffreys’ images documenting the Magnolia Company refinery in Beaumont, Texas, circa 1912.

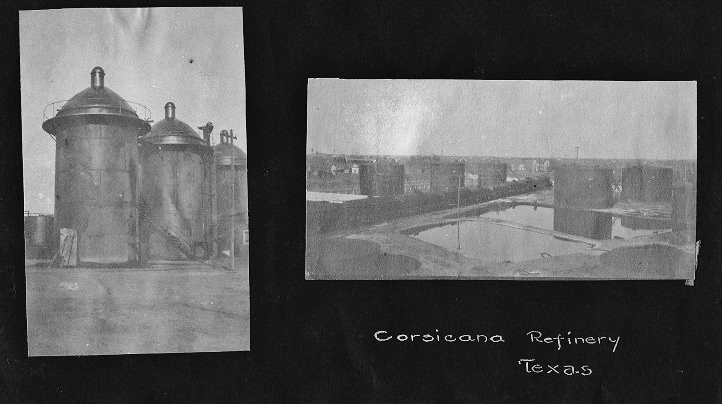

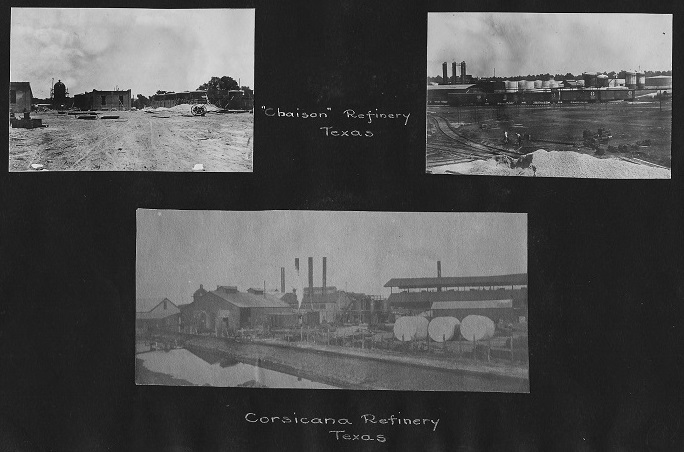

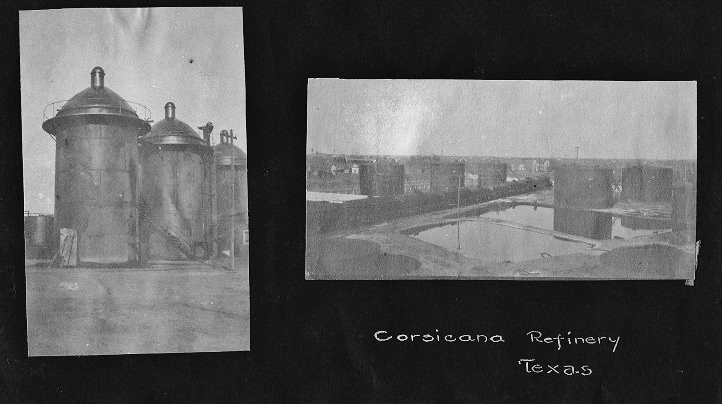

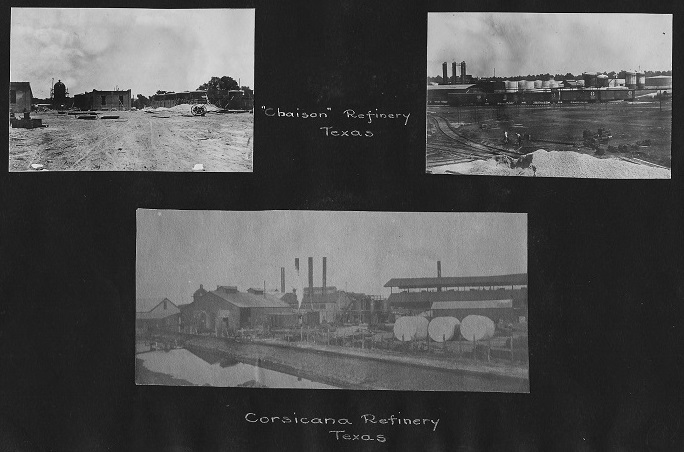

In addition to images of the Magnolia oil refinery, Albert Jeffreys photographed other circa 1910 refineries, including one near Corsicana and the “Chaison Refinery” below.

Both Albert and wife Florence enjoyed fishing in Galveston Bay between his frequent surveying trips in Texas in 1910 – and a visit to the pipeline pumping station in Moores, Louisiana.

Albert “Jeff” and “Flo” Jeffreys lived in Kirksville, Texas, and enjoyed fishing out of Port Bolivar around 1911.

With many family photos in the process of being preserved for posterity, Albert “Jeff” Jeffery’s petroleum career continues to fascinate his granddaughter. “I still intend to do more looking as it is a puzzle full of interesting pieces,” says Sheila.

“For example, my grandfather’s father worked for a British oil company and my grandfather’s son Stanley Rex Jeffreys was a geologist with the landmark geology survey of California, which I believe was completed sometime in the 1950s and was part of the concerted effort to identify oil producing areas in California,” Shelia explains. “So, there were three generations of Jeffreys oil men.”

Geologic mapping in California began in 1826 when the first geologic survey in the state was done by a British naval officer, according to History of Geologic Maps of California of the California Geological Survey.

1901 Gusher at Spindletop

Albert Jeffreys worked in Texas oilfields just a few years after a famous oil discovery about three miles south of Beaumont. The January 10, 1901, “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill would soon lead to southeastern Texas producing more oil in one day than the rest of the world’s oilfields combined. Major petroleum companies like Texaco got started there.

Both the Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum and the Texas Energy Museum in Beaumont tell the story of the Spindletop well, a “wildcat” discovery that created the greatest petroleum boom in America – far exceeding the first U.S. oil discovery well in 1859 in Pennsylvania.

A replica wooden derrick recreates the excitement of a major oil discovery of January 10, 1901. Photo courtesy Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum at Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas.

Gladys City, now partially recreated on the museum’s grounds, was originally envisioned by Patillo Higgins of the Gladys City Oil, Gas and Manufacturing Company. Known as the Prophet of Spindletop, he predicted oil would be found near the city he designed in 1892. Spindletop launched the modern petroleum industry a few years later.

Learn more about finding a museum to preserve family photos at Oil Families.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2021 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | May 6, 2014 | Petroleum Companies

Discovered in 1901, Spindletop created the modern U.S. petroleum industry, changed the future of American transportation – and brought many new oilfield technologies. A newspaper’s questionable geology attempts to describe the new Texas oilfield.

Beaumont was just another Texas Gulf Coast town until 1901 when a nearby hill known to locals as “Spindletop” changed U.S. petroleum history – and inspired birth of Beaumont Confederated Oil & Pipe Line Company.

Far from previous production, a wildcat well erupted oil in on January 10 that would produce more oil than anyone ever imagined.

The “Lucas Gusher” spawned future petroleum giants, including Gulf Oil, The Texas Company (Texaco) and Humble Oil (Exxon). (more…)