by Bruce Wells | May 19, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

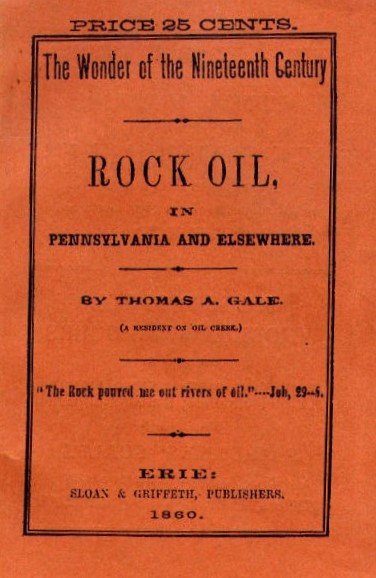

Less than 10 months after Edwin L. Drake and his driller William “Uncle Billy” Smith completed the first commercial U.S. oil well on August 27, 1859, along Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, Thomas A. Gale wrote a detailed study about rock oil — and helped launch the petroleum age.

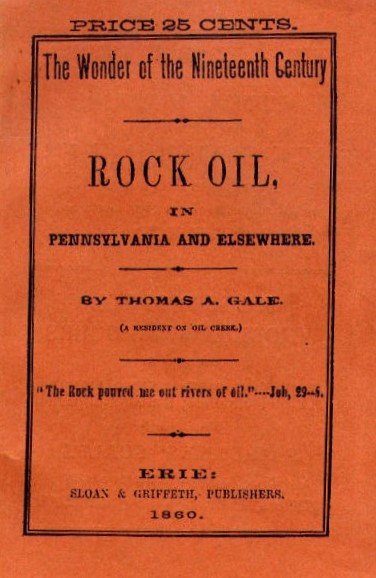

Published in 1860, The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere described a radical fuel source for the popular lamp fuel kerosene, which had been made from coal for more than a decade.

“Those who have not seen it burn may rest assured its light is no moonshine; but something nearer the clear, strong, brilliant light of day,” Gale declared in his 25-cent pamphlet printed in Erie by Sloan & Griffith Company.

Thomas Gale’s 80-page pamphlet in 1860 marked the beginning of the petroleum age, illuminated with kerosene lamps.

“In other words, rock oil emits a dainty light; the brightest and yet the cheapest in the world; a light fit for Kings and Royalists, and not unsuitable for Republicans and Democrats,” Gale added.

Oil in Rocks

Gale’s descriptions of the value of petroleum helped launch investments in new exploration companies, especially as he noted the commercial qualities of Pennsylvania oil for refining into kerosene, the distilled “coal oil” invented in 1848 by Canadian chemist Abraham Gesner.

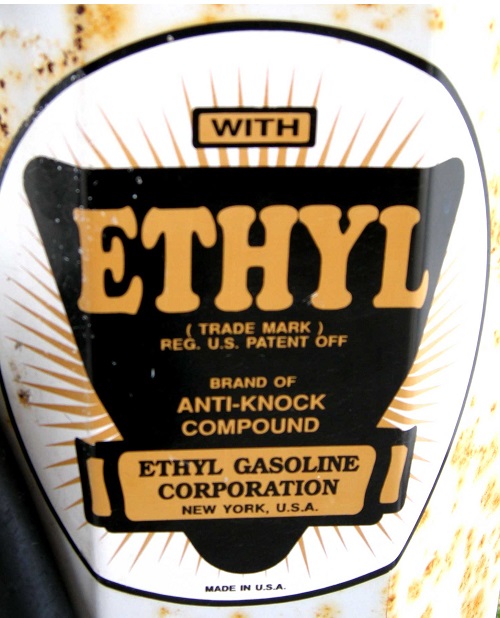

Historians regard the 80-page publication as the first book about America’s petroleum industry. The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere was almost forgotten until 1952, when the Ethyl Corporation of New York republished the work. Only three original copies were known to exist.

“Not by the widest stretch of the imagination could Thomas Gale have realized, when he put down his pen on June 1, 1860, that he had written a book destined to become one of the rarest of all oil books,” proclaimed the Ethyl historian when the company republished Gale’s book.

Ethyl Corporation noted the scarcity of copies of the book had prevented “all but a few historians” from giving the book the attention it deserved.

“Gale wrote his book to satisfy a public desire for more information about petroleum. Newspapers had carried belated accounts of Drake’s discovery well, and the mad scramble for oil that followed, but actually the world knew little about petroleum.”

“The Rock poured…”

The book’s 11 chapters explain practical aspects of the new petroleum industry. Chapters one and two, “What is Rock Oil?” and “Where is the Rock Oil found?” were followed by “Geological Structure of the Oil Region.”

Chapters four through six explained the early technologies (and costs) for pumping the oil, while the next two chapters examine “Uses of Rock Oil.” The final three chapters offered “Sketches of several oil wells,” “History of the Rock Oil Enterprise,” and “Present condition and prospects of Rock Oil interests in different localities.”

Chapter three in The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere features the “geological structure of the oil region,” today part of Oil Creek State Park in northwestern Pennsylvania.

Originally published by Sloan & Griffith of Erie, Pennsylvania, the 1860 cover noted the author as “a resident of Oil Creek” and included a biblical quote, “The Rock poured me out rivers of oil,” from Job, 29:6.

In addition to mysteriously burning gasses and “tar pits,” explorers for millennia have referenced signs of coal, bitumen, and substances very much like petroleum — a word derived from the Latin roots of petra, meaning “rock” and oleum meaning “oil.”

But did Thomas Gayle’s 1860 work produce the first book about oil as Ethyl Corporation historians believed when the company reprinted it in 1952? In fact, there have been many references to natural oil seeps recorded millennia ago (including in the Bible), according to a geologist who has researched the earliest sightings of petroleum.

Illuminating Petroleum

Several years before the 1859 oil discovery in Pennsylvania, businessman George Bissell hired a prominent Yale chemist to study the potential of oil and its products to convince potential investors (see George Bissell’s Oil Seeps).

“Gentlemen, it appears to me that there is much ground for encouragement in the belief that your company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive processes, they may manufacture very valuable products,” reported Benjamin Silliman Jr. in 1855.

Silliman’s groundbreaking “Report on the Rock Oil, or Petroleum, from Venango Co., Pennsylvania, with Special Reference to its Use for Illumination and Other Purposes,” convinced the petroleum industry’s earliest investors to drill at Titusville. Cable-tool technology developed for brine wells would drill the well.

According to historian Paul H. Giddens in the 1939 classic, The Birth of the Oil Industry, Silliman’s 1855 report, “proved to be a turning-point in the establishment of the petroleum business, for it dispelled many doubts about its value.”

The Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company would evolve into the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut, which became America’s first oil company after Drake completed the first U.S. commercial well drilled seeking oil in 1859.

Rock Oil Products

In addition to providing oil for refining into kerosene lamps (and someday rockets), oilfield discoveries led to many products. Early petroleum products included axle greases, an oilfield paraffin balm, and in Easton, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons.

Further, oil offered an improved asphalt prior to the first U.S. auto show in November 1900 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

Ethyl Corporation was established in 1923 by General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey,

Responding to consumer demand for better automobile gasoline, General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey established the Ethyl Corporation in 1923. The company initially downplayed the danger of tetraethyl lead. Leaded gas would be banned for use in cars in the 1970s

Importantly, high-octane leaded aviation fuel proved vital for victory in World War II — and the additive still fuels many piston-engine aircraft and racecars.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere (1952); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1939); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Oil Book of 1860.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/first-oil-book-of-1860. Last Updated: May 17, 2025. Original Published Date: May 31, 2020.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 16, 2025 | Petroleum Products

When Phillips Petroleum scientists invented a new plastic in the early 1950s, getting it from lab to market proved difficult. Enter Wham-O.

Research scientists in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1951 discovered how to make a durable, high-density polyethylene, and the marketing executives at their oil and natural gas company named it Marlex. But Phillips Petroleum sales reps searched in vain for buyers of the new plastic until the Wham-O toy company found it ideal for making hoops and flying platters.

Prompted by a post World War II boom in demand for plastics, Phillips Petroleum Company invested $50 million to bring its own miracle product — Marlex — to market in 1954. With a high melting point and tensile strength, the synthetic polymer would stand out from the company’s thousands of patents.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 23, 2024 | This Week in Petroleum History

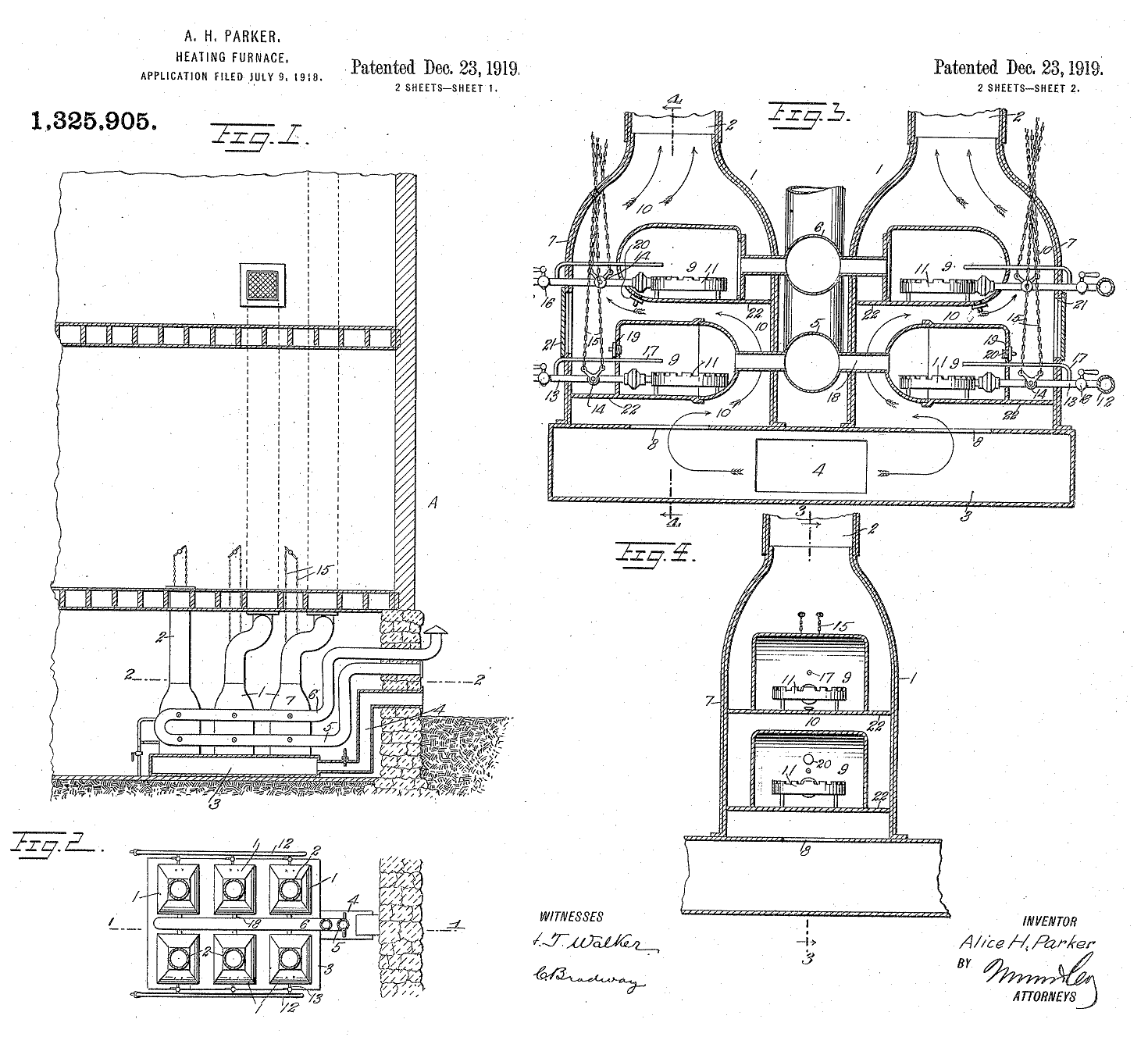

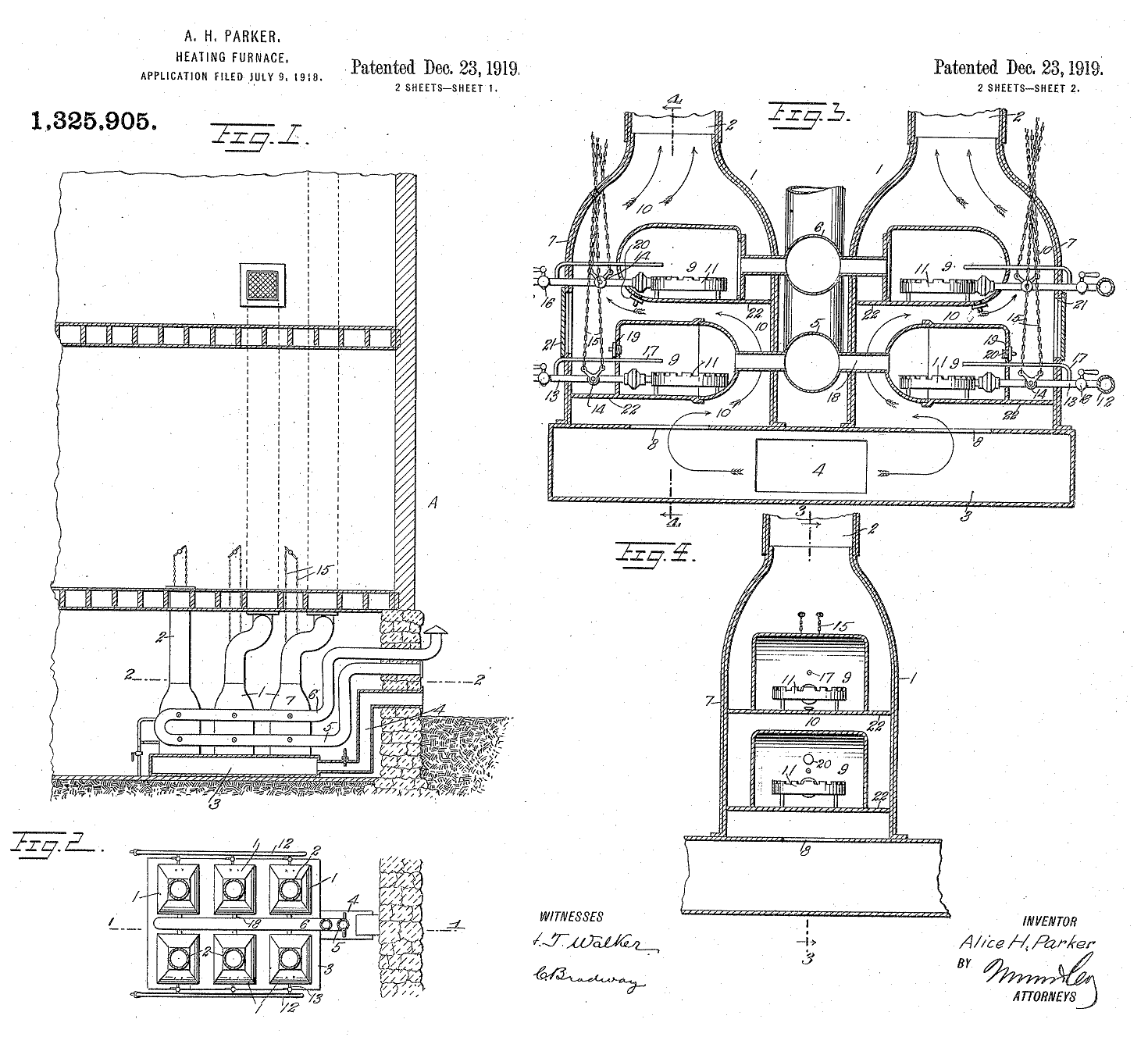

December 23, 1919 – Home Gas Heating System –

When most American homeowners were stocking up on wood and coal to heat their homes, Alice H. Parker patented a gas furnace system with adjustable ducts. The 1910 graduate of Howard University described her patent (no. 1,325,905) as a reliable gas-heating furnace, with “individual hot air ducts leading to different parts of the building, so that heating of the various rooms or floors can be regulated as required.”

Alice Parker in 1919 patented her design for a gas furnace with adjustable hot air ducts.

Although Parker’s patent was not the first for a gas furnace design, according to Heat Treat Today, “It was unique in that it incorporated a multiple yet individually controlled burner system.” By 1927, more than 250,000 U.S. homeowners were heating with natural gas.

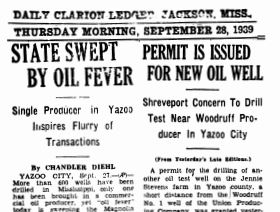

December 23, 1943 – Oilfield discovered in Mississippi

Gulf Oil Company discovered a new Mississippi oilfield at Heidelberg in Jasper County. The company’s surveyors had recognized the geological potential of the area southeast of Jackson as early as 1929, and Gulf Oil used newly developed seismography methods and core drilling technologies to look for oil-bearing formations.

Mississippi’s petroleum industry began with a 1939 oilfield discovery in Yazoo County.

The 1943 discovery well revealed one of the state’s largest oilfields since the Tinsley oil-producing formation in 1939. The first major Mississippi oil well was drilled following a geological survey by a young geologist — who had sought a suitable Yazoo County clay to mold cereal bowls for children. “It all began quite independently of any search for oil,” a historian later explained.

Learn more in the First Mississippi Ol Wells.

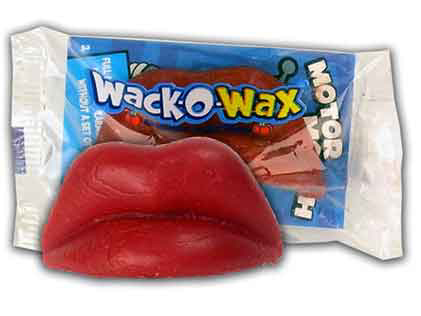

December 24, 1997 – Petroleum Products in a Holiday Classic

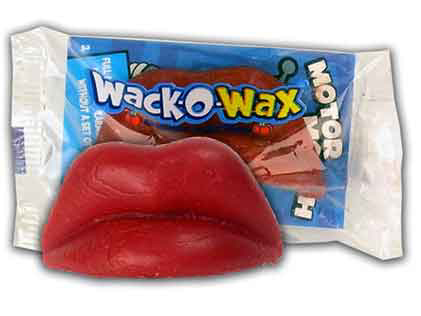

The TNT network began airing “24 Hours of A Christmas Story,” an annual marathon of an independent film made in 1983. The circa 1940 movie’s popularity — and merchandise sales — led to more marathons on TBS. In addition to the plastic leg lamp with black nylon polymer stocking, another petroleum product featured: a paraffin-based novelty candy.

“A Christmas Story” featured Ralphie, his 4th-grade classmates, and an unusual petroleum product. Photos courtesy MGM Home Entertainment.

Paraffin makes its appearance when Ralphie Parker and his fourth-grade classmates smuggle Wax Fangs into class. An older generation may recall the peculiar disintegrating flavor of Wax Lips, Wax Moustaches, and Wax Bottles. Few realize the candy started in the U.S. oil patch — as did another oilfield paraffin product, Crayola Crayons.

Learn more in the Oleaginous History of Wax Lips.

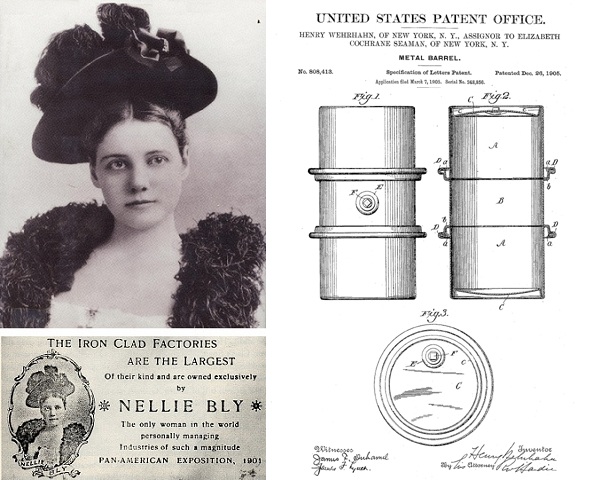

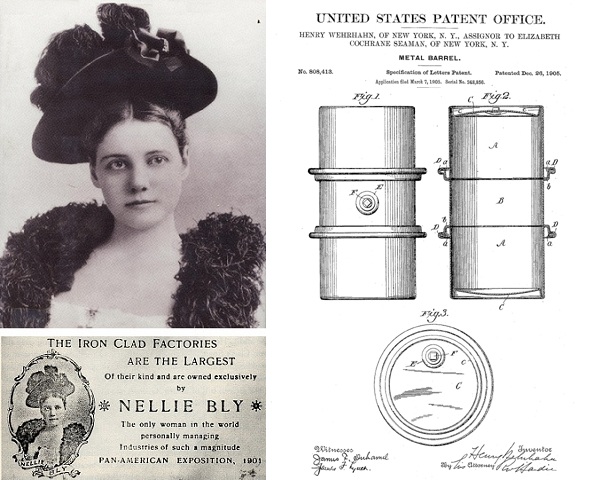

December 26, 1905 – Nellie Bly’s Ironclad 55-Gallon Metal Barrel

Inventor Henry Wehrhahn of Brooklyn, New York, received two patents that would lead to the modern 55-gallon steel drum. He assigned both to his employer, the famous journalist Nellie Bly, who was president of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company.

“My invention has for its object to provide a metal barrel which shall be simple and strong in construction and effective and durable in operation,” Wehrhahn noted. After receiving a second patent for detaching and securing a lid, he assigned them to Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman (Nellie Bly), the recent widow of the company’s founder, Robert Seaman.

Nellie Bly was assigned a 1905 patent for the “Metal Barrel” by its inventor, Henry Wehrhahn, who worked at her Iron Clad Manufacturing Company.

Well-known as a reporter for the New York World, Bly manufactured early versions of the “Metal Barrel” that would become today’s 55-gallon steel drum. Wehrhahn later became superintendent of a steel tank company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Learn more in the Remarkable Nellie Bly’s Oil Drum.

December 28, 2017 – Smithsonian features Oilfield Nitro Factory

“The True Story of Mrs. Alford’s Nitroglycerin Factory,” proclaimed an article in Smithsonian magazine about the early oil industry. “Mary Alford remains the only woman known to own a dynamite and nitroglycerin factory,” the magazine added about the 19th-century nitroglycerin factory owner. With the Bradford, Pennsylvania, oilfield in 1881 accounting for 83 percent of all U.S. oil production, Mrs. Alford was reported to be “an astute businesswoman in the midst of America’s first billion-dollar oilfield.”

Learn more in Mrs. Alford’s Nitro Factory.

December 28, 1930 – Well reveals extent of East Texas Oilfield

Three days after Christmas, a major oil discovery on the farm of the widow Lou Della Crim of Kilgore revealed the extent of the giant East Texas oilfield. Her son, J. Malcolm Crim, had ignored advice from most geologists and explored about 10 miles north of the field’s discovery well, drilled in October by Columbus “Dad” Joiner on the farm of another widow, Daisy Bradford.

“Mrs. Lou Della Crim sits on the porch of her house and contemplates the three producing wells in her front yard,” notes the caption of this undated photo courtesy Neal Campbell, Words and Pictures.

The Lou Della Crim No. 1 well erupted oil on a Sunday morning while “Mamma” Crim was attending church. The well initially produced 20,000 barrels of oil a day.

One month later and 15 miles farther north, a third wildcat well drilled by Fort Worth wildcatter W.A. “Monty” Moncrief confirmed the true size of the largest oilfield in the continental United States. The East Texas field would encompass more than 480 square miles.

Learn more in Lou Della Crim Revealed.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Oil in the Deep South: A History of the Oil Business in Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, 1859-1945 (1993); How Sweet It Is (and Was): The History of Candy (2003); Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist

(1993); How Sweet It Is (and Was): The History of Candy (2003); Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist (1994); Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017); Images of America: Around Bradford

(1994); Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017 (2017); Images of America: Around Bradford (1997); The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field

(1997); The Black Giant: A History of the East Texas Oil Field (2003). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2003). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 16, 2024 | Petroleum Products

Petroleum paraffin soon found its way into candles, crayons, chewing gum…and a peculiar wax candy.

When Ralphie Parker and his 4th-grade classmates dejectedly handed over their Wax Fangs to Mrs. Shields in “A Christmas Story,” a generation might be reminded of what a penny used to buy at the local Woolworth’s store. But there is far more to these paraffin playthings than a penny’s worth of fun.

It’s hard to recall a time when there were no Wax Lips, Wax Moustaches, or Wax Fangs for kids to smuggle into classrooms. Many grownups may remember the peculiar disintegrating flavor of Wax Lips from bygone Halloweens and birthday parties, but few know where these enduring icons of American culture started. The answer can be found by way of the oil patch.

Released on November 18, 1983, “A Christmas Story” featured Ralphie, his 4th-grade classmates – and a popular petroleum product. Photos courtesy MGM Home Entertainment.

Beginning with the August 1859 first commercial U.S. oil well, Pennsylvania oilfields quickly brought an important new source for refining kerosene. “This flood of American petroleum poured in upon us by millions of gallons, and giving light at a fifth of the cost of the cheapest candle,” wrote British chandler James Wilson in 1879.

As kerosene lamps replaced candles for illumination, the much-reduced candle business turned from tallow to versatile paraffin.

A byproduct of kerosene distillation, paraffin found its way from refinery to marketplace in candles, sealing waxes and chewing gums. Ninety percent of all candles by 1900 used paraffin as the new century brought a host of novel uses. Thomas Edison’s popular new phonographs also needed paraffin for their wax cylinders.

Concord Confections, part of Tootsie-Roll Industries, continues to produce Wax Lips and other paraffin candies for new generations of schoolchildren.

Crayons were introduced by the Binney & Smith Company in 1903 and were instantly successful. Alice Binney came up with the name by combining the French word for chalk, craie, with an English adjective meaning oily, oleaginous: Crayola (see Carbon Black and Oilfield Crayons).

In New York City, after collecting unrefined waxy samples from Pennsylvania oil wells, Robert Chesebrough invented a method for turning paraffin into a balm he called “petroleum jelly,” later “Vaseline.” His product also led to a modern cosmetic giant (learn more in The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes).

Paraffin Lips, Fangs, and Horses Teeth

An inspired Buffalo, New York, confectioner soon used fully refined, food-grade paraffin and a sense of humor to find a niche in America’s imagination. When John W. Glenn introduced children to paraffin “penny chewing gum novelties,” his business boomed. By 1923, his J.W. Glenn Company employed 100 people, including 18 traveling sales representatives.

Glenn Confections became the wax candy division of Franklin Gurley’s nearby W.&F. Manufacturing Company. There, the ancestors of Wax Lips chattered profitably down the production line. Among the most popular of these novelties at the time were Wax Horse Teeth (said to taste like wintergreen).

By 1939, Gurley was producing a popular series of holiday candles for the Socony-Vacuum Oil Company using paraffin from a nearby refinery at Olean, New York — once home to the world’s largest crude oil storage site. A field of metal tanks, some holding 20,000 gallons of paraffin, stood next to Gurley’s W.&F. Manufacturing Company in Buffalo.

Glenn Confections, the candy division of W. & F. Manufacturing Company, produced Fun Gum Sugar Lips, Wax Fangs, and Nik-L-Nips.

Decorative and scented paraffin candles soon became the company’s principal products, accounting for 98 percent of W.&F. Manufacturing sales. Gurley’s “Tavern Candle” Santas, reindeer, elves and other colorful Christmas favorites today are prized by collectors on eBay, as are his elaborately molded Halloween candles.

Glenn Confections, the W.&F. wax candy division, has continued to manufacture the popular Fun Gum Sugar Lips and Wax Fangs, with small, wax bottles — Nik-L-Nips — available from the Old Time Candy Company.

In Emlenton, Pennsylvania, a few miles south of Oil City, the Emlenton Refining Company (and later the Quaker State Oil Refining Company) provided the fully refined, food-grade paraffin for the bizarre but beloved treats. Retired Quaker State employee Barney Lewis remembers selling Emlenton paraffin to W.&F. Manufacturing.

During a 2005 interview, Lewis noted, “It was always fun going to the plant…they were very secret about how they did stuff, but you always got a sample to bring home,” adding, “Wax Lips, Nik-L-Nips…the little Coke bottle-shaped wax, filled with colored syrup.”

Concord Confections, a small part of Tootsie-Roll Industries, continues to produce Wax Lips and other paraffin candies for new generations of schoolchildren. The modern petroleum industry produces an astonishing range of products for consumers. But among the many products that find their history in the oilfield, few are as unique and peculiar as Wax Lips.

In December 2007, “A Christmas Story” was ranked the number one Christmas film of all time by AOL. Set in 1940, the movie has been shown in an annual marathon since 1997.

Among the waxy petroleum products featured is a polymer “major award” — the plastic leg-lamp with the black nylon stocking.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Sweet!: The Delicious Story of Candy (2009); How Sweet It Is (and Was): The History of Candy (2003). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oleaginous History of Wax Lips.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/an-oleaginous-history-of-wax-lips. Last Updated: December 15, 2024. Original Published Date: December 1, 2006.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.