by Bruce Wells | Nov 19, 2024 | Petroleum Pioneers

Rise and fall of an infamous Pennsylvania boom town.

As the Civil War ended, oil discoveries at Pithole Creek in Pennsylvania created a headline-making boom town for the young U.S. petroleum industry. As wells drilled deeper into geological formations, the first gushers arrived — adding to “black gold” fever sweeping the country.

America’s oil production began in 1859 with Edwin L. Drake’s historic first commercial oil well drilled along a creek at Titusville. Drilled near natural oil seeps, his oilfield discovery at a depth of 69.5 feet led to a rush of exploration in the remote Allegheny River Valley.

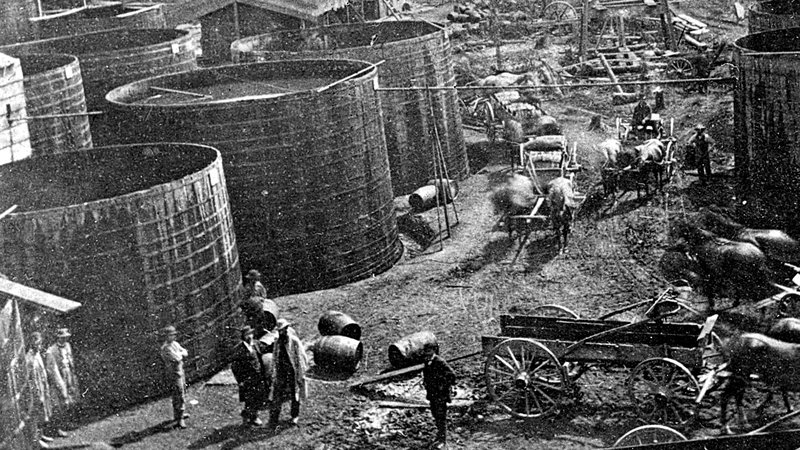

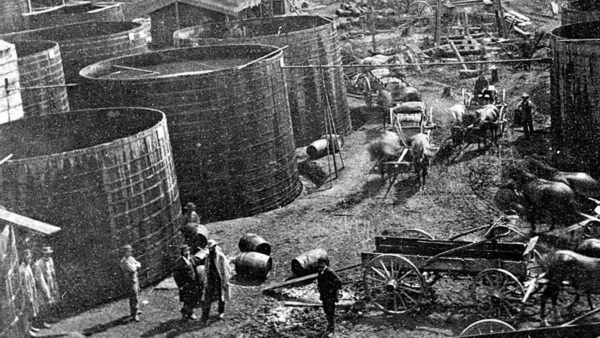

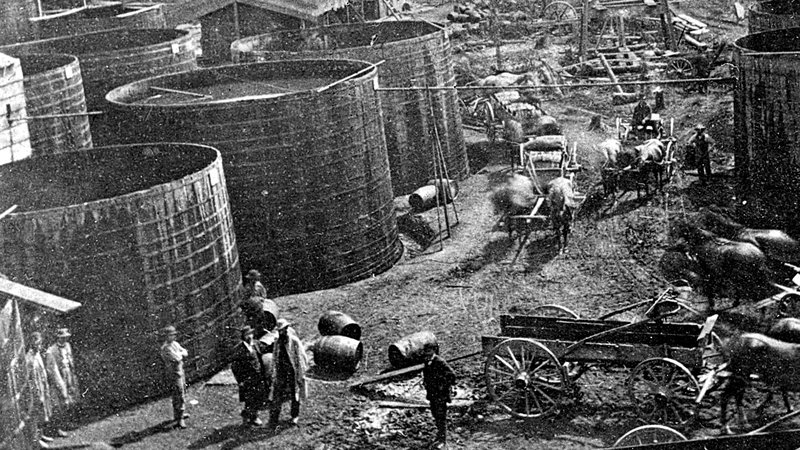

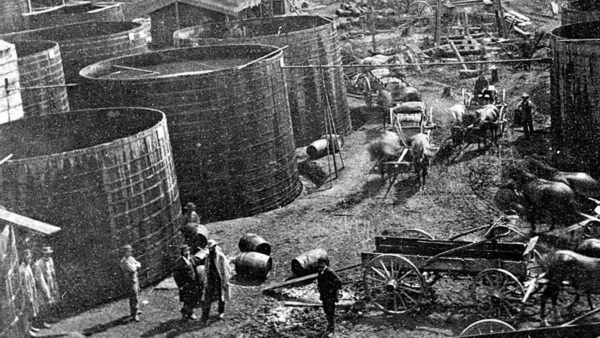

The new petroleum industry’s transportation infrastructure struggled as oil tanks crowded Pithole, Pennsylvania. In 1865, the first oil pipeline linked an oil well to a railroad station about five miles away. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

In 1864, businessman Ian Frazier found oil at Cherry Creek. After making a quick $250,000, Frazier looked for another opportunity in the hills and valleys providing oil to new Pittsburgh refineries making kerosene for lamps.

Frazier hired a diviner to search along Pithole Creek, which smelled like “sulfur and brimstone,” according to historian Douglas Wayne Houck. “He went to the creek and followed the diviner around until the forked twig dipped, pointing to a specific spot on the ground,” Houck noted in 2014.

Exploration techniques would improve, but with the science of petroleum geology still in the future, the oil industry (soon natural gas) already had begun drilling the first “dry holes.”

Pennsylvania Oil Geysers

Although Ian Frazier’s United States Oil Company’s steam powered, cable-tool derrick first drilled a dry hole, a second well erupted spectacularly on January 7, 1865, producing 650 barrels of oil a day. The Frazier well, proclaimed by Houck as the first U.S. oil gusher, brought a flood of drillers and speculators to Pithole Creek.

Two more wells erupted black geysers on January 17 and January 19, each flowing at about 800 barrels of oil a day (invention of a practical blowout preventer was still half a century away). United States Oil Company subdivided its property and began selling lots for $3,000 per half-acre plot.

The Titusville Herald proclaimed Pithole as having “probably the most productive wells in the oil region of Pennsylvania, Houck explained in his Energy & Light in Nineteenth-Century Western New York.

Fortunes were being made and lost in the oil regions — see the cautionary tale of the Legend of “Coal Oil Johnny.”

As the news spread through Venango County, “everyone came to the Pithole area to try their luck,” noted one reporter. Many were Confederate and Union war veterans. And as more successful wells came in, about 3,000 teamsters rushed to Pithole to haul out the barrels of oil. It was hard to keep up.

Managed by the Drake Well Museum, the Pithole Visitors Center includes a diorama of the vanished town. Photo by Bruce Wells.

There were many reasons behind the Pithole oil boom, including a flood of paper money at the end of the Civil War. Many returning Union veterans had currency and were eager to invest — especially after reading newspaper articles about oil gushers and boom towns. Thousands of veterans also wanted jobs after long months on army pay.

By May 1865, the town was home to 57 hotels, many shops, and its own daily newspaper. It had the third busiest post office in Pennsylvania — handling 5,500 pieces of mail a day.

Pithole’s Lady Macbeth

In December 1865, Shakespearean tragedienne Miss Eloise Bridges appeared as Lady Macbeth in America’s first famously notorious oil boom town.

Shakespearean tragedienne Eloise Bridges appeared on the Pithole stage in 1865.

Bridges appeared at Murphy’s Theater, the biggest building in a town of more than 30,000 teamsters, coopers, lease-traders, roughnecks, and merchants. Three-stories high, the building had 1,100 seats, a 40-foot stage, an orchestra, and chandelier lighting by Tiffany.

Bridges was the acclaimed darling of the Pithole stage. Eight months after she departed for new engagements in Ohio, the oilfield at Pithole ran dry; the most famous U.S. boom town collapsed into empty streets and abandoned buildings.

Pennsylvania oil region visitors today walk the grass streets of the first oil boom ghost town.

First Oil Pipeline

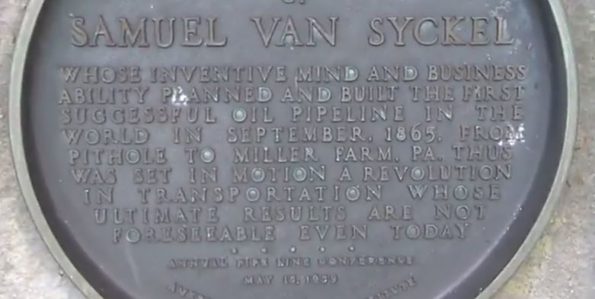

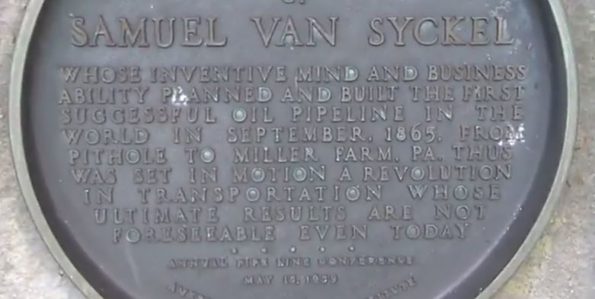

As Pithole oil tanks overflowed (and tank fires from accidents and lightening strikes increased), oil shipper Samuel Van Syckel conceived an infrastructure solution that became an engineering milestone.

In 1865, his newly formed Oil Transportation Association put into service a two-inch iron line linking the Frazier well to the Miller Farm Oil Creek Railroad Station, about five miles away.

“The day that the Van Syckel pipe-line began to run oil a revolution began in the business. After the Drake well it is the most important event in the history of the Oil Regions,” declared Ida Tarbell about the technology in her 1904 book, History of the Standard Oil Company.

Visitors walk the grassy paths of Pithole’s former streets and see artifacts, including antique steam boilers. Volunteers “mow the streets.” Photo by Bruce Wells.

With 15-foot welded joints and three 10-horsepower Reed and Cogswell steam pumps, the pipeline transported 80 barrels of oil per hour — the equivalent of 300 teamster wagons working for 10 hours. Convinced their livelihood was threatened, teamsters attempted to sabotage the oil pipeline until armed guards intervened.

Unfortunately for Van Syckel, Pithole oil storage tanks continued to catch fire even as the Frazier well production began to decline. Other wells were beginning to run dry when in 1866, fires spread out of control and burned 30 buildings, 30 oil wells and 20,000 barrels of oil.

“Pithole’s days were numbered,” concluded historian Houck about the fire, which was documented by early oilfield photographer John H. Mather. “Buildings were taken down and carted off. A few people hung around until 1867.”

The American Petroleum Institute in 1959 dedicated a plaque on the grounds of the Drake Well Museum as part of the U.S. oil centennial.

From beginning to end, America’s famous oil boom town had lasted about 500 days. Pithole was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 20, 1973.

A visitors’ center added in 1975 has been maintained by the Drake Well Museum. The center contains exhibits, including a scale model of the city at its peak and a small theater. Volunteers “mow the streets” on the hillside so that tourists can stroll where the petroleum boom town once flourished.

Among the Pennsylvania oil region’s earliest — and most infamous — investors was the actor John Wilkes Booth (see the Dramatic Oil Company).

Oil Town Aero Views

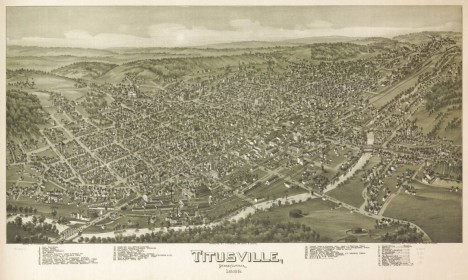

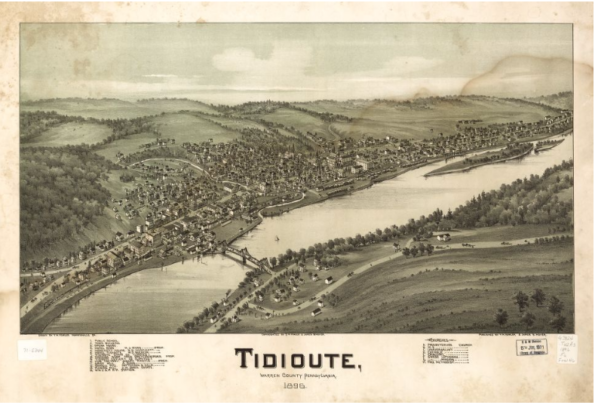

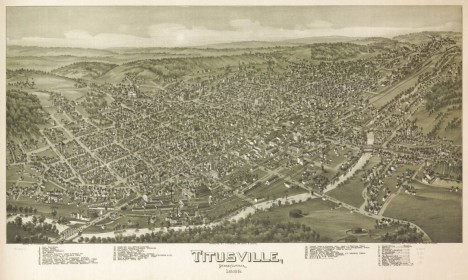

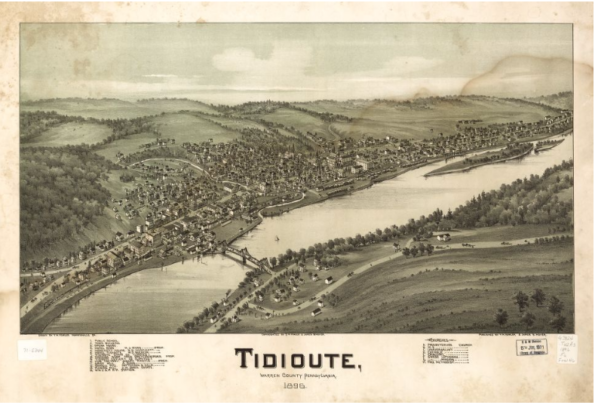

During the late 19th century, “bird’s-eye views” became a widely popular way to map U.S. cities and towns. Cartographer Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler created many of the best panoramic maps that he also called “aero views.”

The wealthy Pennsylvania oil regions attracted the attention of Fowler, who in 1885 moved his family to Morrisville, where he worked for the next 25 years.

An 1896 Pennsylvania “aero view” map by Thaddeus M. Fowler, courtesy Library of Congress.

Fowler drew maps of Titusville, Oil City, and many petroleum-related boom towns in West Virginia, Ohio — and Texas, where he created dozens of views of cities from 1890 to 1891.

But by far, most of the Fowler maps feature Pennsylvania cities between 1872 and 1922. There are 250 examples of his work in the collection of the Library of Congress. Learn more in Oil Town “Aero Views.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Energy & Light in Nineteenth-Century Western New York (2014); Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny

(2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny (2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oil Boom at Pithole Creek.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/pithole-creek/. Last Updated: November 19, 2024. Original Published Date: March 15, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 7, 2024 | This Week in Petroleum History

October 7, 1859 – First U.S. Oil Well catches Fire –

The wooden derrick and engine house of America’s first oil well erupted in flames along Oil Creek at Titusville, Pennsylvania. The well had been completed the previous August by Edwin L. Drake for George Bissell and the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut. Working with driller William “Uncle Billy” Smith, Drake used steam-powered cable-tool technology.

The first U.S. oil well fire began when Uncle Billy inspected a vat of oil with an open lamp. When the lamp’s flame set gases alight, the conflagration consumed the derrick, the stored oil, and the driller’s home. Drake and Seneca Oil Company would quickly rebuild at the already famous well site.

Learn more in First Oil Well Fire.

October 8, 1915 – Elk Basin oilfield discovered in Wyoming

An exploratory well drilled in a remote Wyoming valley opened the giant Elk Basin oilfield. Completed by the Midwest Refining Company near the Montana border, the wildcat well produced 150 barrels of high-grade “light oil” a day. The oil needed little refining to provide quality lubricants.

“Gusher coming in, south rim of the Elk Basin field, 1917.” Photo courtesy American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

Geologist George Ketchum first recognized the potential of the basin as a source of oil deposits. Ketchum had explored the remote area in 1906 with C.A. Fisher while farming near Cowley, Wyoming. The Elk Basin extended from Carbon County, Montana, into northeastern Park County, Wyoming.

Fisher was the first geologist to map sections of the Bighorn Basin southeast of Cody, Wyoming, where oil seeps had been found as early as 1883. The Wyoming oilfield discovery in unproved territory attracted new ventures like Elk Basin United Oil Company, investors, and oilfield service companies.

Learn more in First Wyoming Oil Wells.

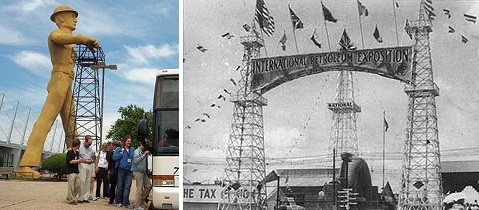

October 8, 1923 – First International Petroleum Exposition and Congress

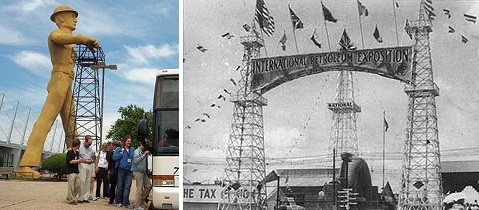

Five thousand visitors attended the rainy opening day of the first International Petroleum Exposition and Congress in downtown Tulsa, an event that would return for almost six decades.

Although still a tourist attraction, the 76-foot-tall Golden Driller arrived decades after Tulsa’s first International Petroleum Exposition in 1923.

With annual attendance growing to more than 120,000, Mid-Continent Supply Company of Fort Worth introduced the original Golden Driller of Tulsa at the expo in 1953. Economic shocks beginning with the 1973 OPEC oil embargo depressed the industry and after 57 years, the International Petroleum Exposition ended in 1979.

October 9, 1999 – Converted Offshore Platform launches Rocket

Sea Launch, a Boeing-led consortium of companies from the United States, Russia, Ukraine and Norway, launched its first commercial rocket using the Ocean Odyssey, a modified semi-submersible drilling platform. After a demonstration flight in March, a Russian Zenit-3SL rocket carried a DirecTV satellite to geostationary orbit.

Ocean Odyssey, a modified semi-submersible drilling platform, became the world’s first floating equatorial launch pad in 1999. Photo courtesy Sea Launch.

In 1988, the former drilling platform had been used by Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) for North Sea explorations. The Ocean Odyssey made 36 more rocket launches until 2014, when the consortium ended after Russia illegally annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula.

Learn more in Offshore Rocket Launcher.

October 10, 1865 – Oil Pipeline constructed in Pennsylvania

A two-inch iron pipeline began transporting oil five miles through hilly terrain from a well at booming Pithole, Pennsylvania, to the Miller Farm Railroad Station at Oil Creek. With their livelihoods threatened, teamsters attempted to sabotage the pipeline, until armed guards intervened. A second oil pipeline would begin operating in December.

Oil tanks at the boom town of Pithole, Pennsylvania, where Samuel Van Syckel built a five-mile pipeline in 1865. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

Built by Samuel Van Syckel, who had formed the Oil Transportation Association, the pipeline used 15-foot welded joints. Three 10-horsepower Reed and Cogswell steam pumps pushed the oil at a rate of 81 barrels per hour. With up to 2,000 barrels of oil arriving daily at the terminal, more storage tanks were soon added. The pipeline transported the equivalent of 300 teamster wagons working for 10 hours.

“The day that the Van Syckel pipeline began to run oil a revolution began in the business,” proclaimed Ida Tarbell in her 1904 History of the Standard Oil Company. “After the Drake well, it is the most important event in the history of the Oil Regions.”

October 13, 1917 – U.S. Oil & Gas Association founded

The United States Oil & Gas Association was founded as the Mid-Continent Oil & Gas Association in Tulsa, Oklahoma, six months after the United States entered World War I. Independent producers Frank Phillips, E.W. Marland, Bill Skelly, Robert Kerr and others established the association to help increase petroleum supplies for the Allies. In 1919, the association formed an Oklahoma-Kansas Division, now the Petroleum Alliance of Oklahoma.

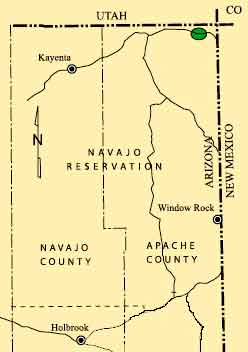

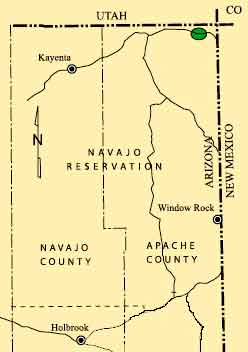

October 13, 1954 – First Arizona Gas Well

After decades of searching for oil, Arizona became the 30th petroleum-producing state when Shell Oil Company completed a natural gas well one mile south of the Utah border on Apache County’s Navajo Indian Reservation. The East Boundary Butte No. 2 well indicated gas production of about 3 million cubic feet per day from depths between 4,540 feet to 4,690 feet, but just a few barrels of oil a day.

Arizona produces oil only from Apache County.

A rancher had reported finding natural oil seeps in central Arizona in the late 1890s, and by 1902, a part-time prospector from Pennsylvania, Joseph Heslet, began a lengthy exploration effort that ended in 1916 after finding traces of oil.

Arizona’s oil production declined after 2015, occasionally reaching 1,000 barrels of crude oil per month. There were no significant proven reserves by 2023, and the state’s few oil wells produced only about 6,000 barrels of oil, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Learn more in First Arizona Oil and Gas Wells.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); Black Gold, Patterns in the Development of Wyoming’s Oil Industry (1997); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America

(2009); Black Gold, Patterns in the Development of Wyoming’s Oil Industry (1997); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America (2000); Offshore Pioneers: Brown & Root and the History of Offshore Oil and Gas

(2000); Offshore Pioneers: Brown & Root and the History of Offshore Oil and Gas (1997); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(1997); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals

(2008); Oil and Gas Pipeline Fundamentals (1993); Arizona Rocks & Minerals: A Field Guide to the Grand Canyon State

(1993); Arizona Rocks & Minerals: A Field Guide to the Grand Canyon State (2010). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2010). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 2, 2024 | Petroleum Pioneers

Driller of first U.S. oil well accidently ignited it 41 days later.

Along Oil Creek at Titusville, Pennsylvania, the wooden derrick and engine house of America’s first well specifically drilled for oil erupted in flames on October 7, 1859. The already famous well had been completed on August 27 by Edwin L. Drake, a former railroad conductor hired by the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Sep 26, 2024 | Petroleum Pioneers

Post-Civil War oilfields launched Allegheny petroleum boom.

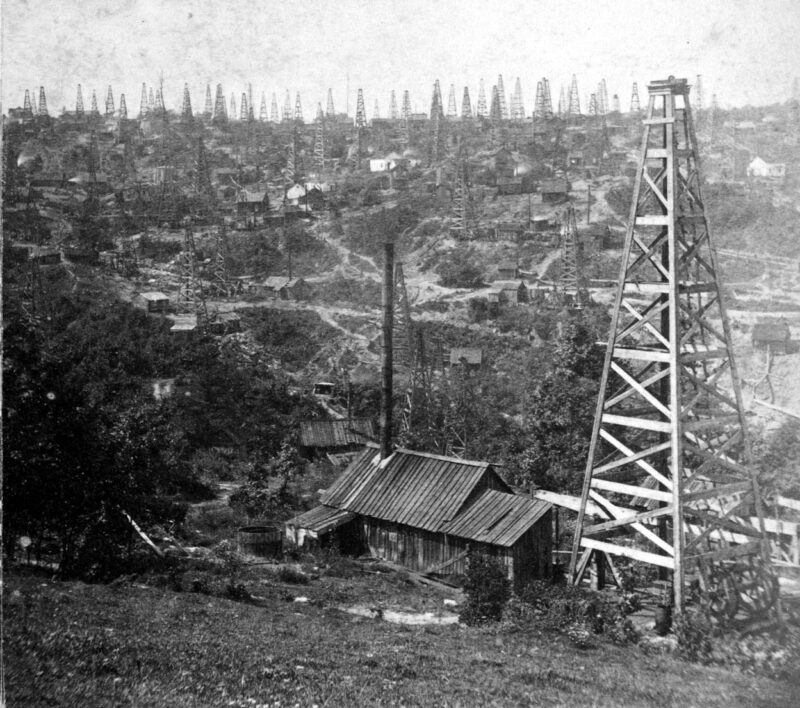

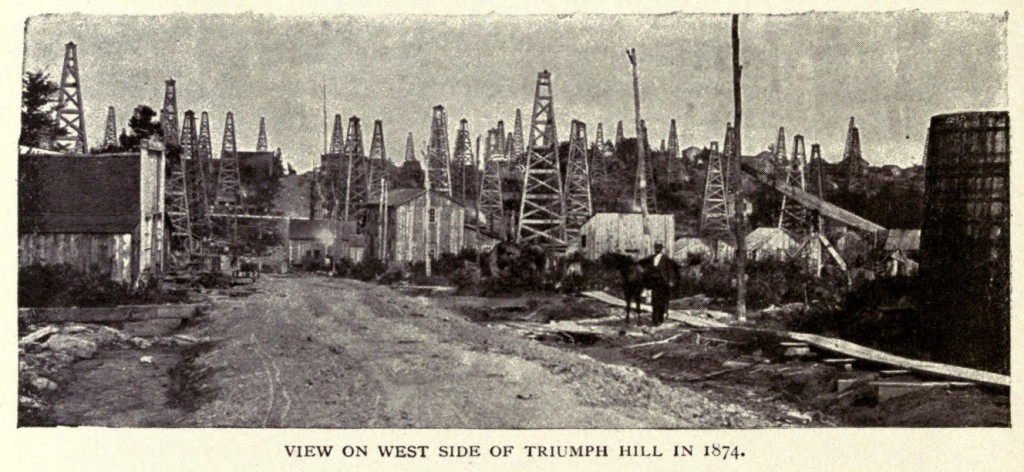

Soon after the Civil War ended and demand for kerosene lamp fuel soared, the rapidly growing U.S. petroleum industry discovered oilfields west of Tidioute, Pennsylvania. Wooden derricks replaced trees on Triumph Hill.

Formerly quiet Pennsylvania hillsides of hemlock woods vanished in early October 1866 when oil fever came to Triumph Hill. The U.S. oil industry was barely seven years old. About 15 miles east of the 1859 first American oil well at Titusville, an 1866 oil discovery at Triumph Hill sparked a rush of uncontrolled development.

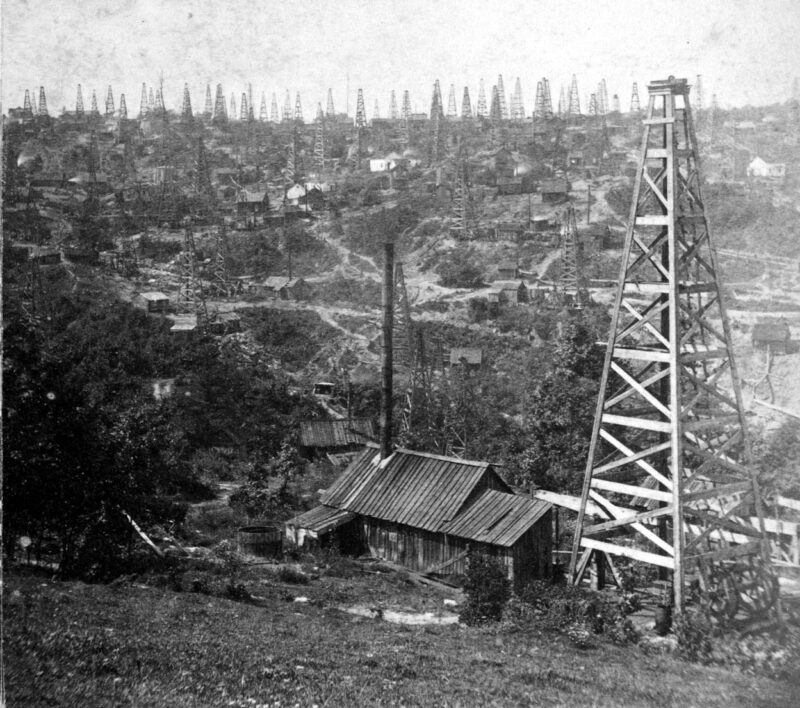

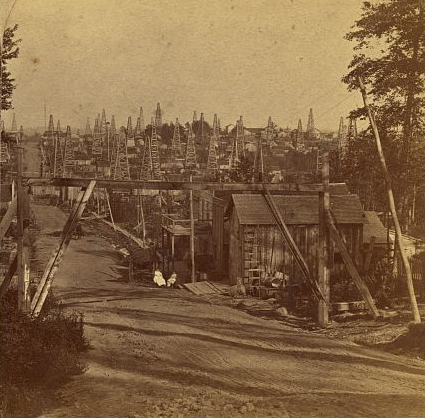

An 1870s photograph of the east side of Triumph Hill, near Tidioute, Pennsylvania, by Frank Robbins of Oil City. Image is right half of a stereo card rendered black and white for clarity from original sepia tone. Photo courtesy Biblioteca Nacional Digital Brazil.

The oil drilling craze would not last long, but boom towns sprang up at Gordon Run and Daniels Run west of Tidioute on Pennsylvania’s Allegheny River.

Like the earlier discoveries at Titusville, Rouseville, and Pithole, hillside trees were turned into derricks and oil storage tanks as drilling intensified. News about a deadly Rouseville oil well fire in April 1861 had been overshadowed by the Civil War.

The excitement at Tidioute (pronounced tiddy-oot) was joined by the roughneck-filled towns of Triumph and Babylon, where “sports, strumpets and plug-uglies, who stole, gambled, caroused and did their best to break all the commandments at once.”

Fresh from the oilfields at booming Pithole 25 miles to the southwest, the infamous Ben Hogan, self-proclaimed “Wickedest Man in the World,” operated a bawdy house on the Triumph hillside along the Allegheny River.

Latest Pennsylvania Oil Boom

Despite growing recognition that crowded drilling reduced reservoir pressures and production, the exploration and production bonanza, which began with the first well on October 4, 1866, prompted a frenzy of drilling as investors tried to cash in before the oil ran out.

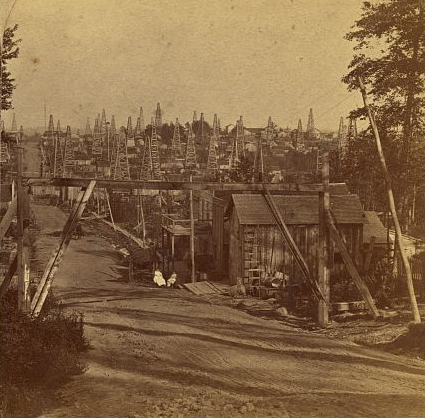

Detail from a Frank Robbins stereographic view of the west side of Triumph Hill, “showing buildings, storage tanks, and derricks, as well as two children sitting in chairs outside a building on Triumph Hill, near Tidioute, Pennsylvania,” — Library of Congress.

By the summer of 1867, Triumph Hill was producing 2,000 barrels of oil a day. The flood of oil bought lower prices — an early example of the petroleum industry’s boom and bust cycles.

Photographer Frank Robbins of Oil City published stereographic images of Triumph Hill, declaring it to be “the most magnificent oil belt (as oil men call a strip of producing land) ever yet discovered.”

He added, “On this belt which is but two miles long, and less than one mile wide — were over 180 producing wells, nearly every one of which was in operation at once.”

Robbins, who moved his studio to Bradford in 1879 when that region was on its way to becoming “America’s first billion-dollar oilfield,” also printed postcards for sale to tourists.

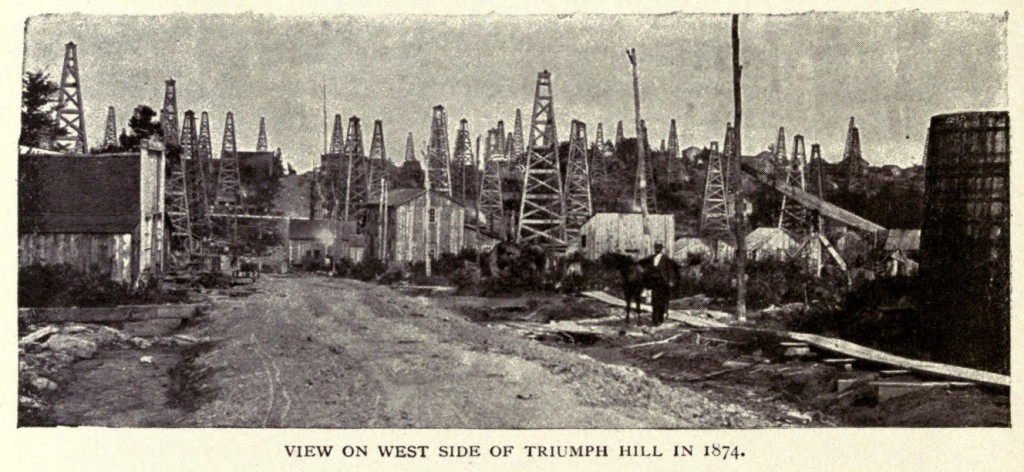

An image from the 1903 edition of “Sketches in Crude-Oil; some accidents and incidents of the petroleum development in all parts of the globe” by James McLaurin.

“Triumph Hill turned out as much money to the acre as any spot in Oildom,” noted James McLaurin in his 1896 book Sketches in Crude-Oil (some accidents and incidents of the petroleum development in all parts of the globe).

Many of the hill’s wells averaged 25 barrels of oil a day, McLaurin reported, adding that “the sand was the thickest – often ninety to one hundred and ten feet – and the purest the oil region afforded.” The tempo of oil exploration around Tidioute and boom town debauchery slowed as the region’s daily production fell.

Drilling discipline and well spacing, reservoir engineering and other oilfield management skills would evolve, but Triumph Hill’s glory dissipated within five years as overproduction drained the field.

Today, Triumph Hill remains one of the many quietly beautiful and forest-covered sites along the Allegheny River Valley that has earned a special place in America’s petroleum history.

Tidioute also is among the earliest panoramic maps of America’s petroleum communities. The view was created by Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler, a popular “bird’s-eye view” cartographer. Learn more about Fowler and his maps in Oil Town “Aero Views.”

Traveling from Pennsylvania to Texas at the turn of the century, Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler created oil town “aero views” – panoramic maps of many of America’s earliest petroleum communities. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Early Oilfield Photography

Pioneer petroleum industry photographers like “Oil Creek Artist” John A. Mather documented Northwestern Pennsylvania boom towns. He and others like Frank Robbins captured views of North American oil booms, according to geologist and historian Jeff Spencer, noting, “Common scenes included oil gushers, oilfield fires, teamsters, and boom towns.”

Frank Robbins documented the emerging 1860s Pennsylvania petroleum industry, Spencer noted in a 2011 article for the journal Oil-Industry History. “He was one of the most prolific producers of stereoscopic views of oilfields in the Oil City and Bradford, Pennsylvania, and Olean, New York area,” Spencer noted.

Robbins photographed scenes from oilfields at Triumph Hill, Tidioute, Petrolia, and Pithole, according to Spencer, who in 2003, published Texas Oil and Gas (Postcard History Series) — learn more in Postcards from the Texas Oil Patch. For more resources on oilfield images, see petroleum photography websites.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania, Images of America (2000); Around Titusville, Pa., Images of America

(2000); Around Titusville, Pa., Images of America (2004); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2004); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Derricks of Triumph Hill.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/triumph-hill-oil. Last Updated: September 26, 2024. Original Published Date: July 3, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Sep 22, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

Learning hard lessons about wasteful overproduction and depleted reservoir pressures.

The discovery of oil along a small creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in August 1859 launched the American petroleum industry. Drilled just 69.5 feet deep at Oil Creek by former railroad conductor Edwin L. Drake, the well produced oil that could be refined into an inexpensive lamp fuel, kerosene.

Drake, who pioneered drilling technology, borrowed a local kitchen water pump to fill the first oil barrels. Early oil production from his and other northwestern Pennsylvania wells brought new refineries to Oil City and Pittsburgh on the Allegheny River.

Four acres close to the Sherman well sold for $220,000 as venture oil capitalists, entrepreneurs, and speculators tried their luck in the newly created petroleum industry.

Demand for kerosene quickly outpaced the inexpensive but volatile lamp fuel camphene. Kerosene also replaced expensive whale oil. A typical four-year whaling voyage returned with 40,000 gallons; New oilfields produced 10 million gallons of kerosene in 1860 alone.

Edwin Drake’s well, drilled for the first U.S. oil company established by George Bissell, brought the country’s first drilling boom as entrepreneurs rushed in. Farmers who leased their land were among the first to benefit.

“Oil Creek was soon taken up and within a relatively short time, the entire valley as far back as into the hillsides, had been leased or purchased,” author Paul Gibbons noted.

With the science of petroleum geology yet to debut, early oil explorers searched near oil seeps and the “rich territory was limited to flats along the streams,” Gibbons added. Natural gas discoveries would later arrive to the benefit of Pittsburgh industries.

Sherman Well of 1861

J.T. Foster’s farm on Pioneer Run hillside off Oil Creek was in “the dry diggings” where few were willing to gamble. Nonetheless, newly minted oil operators gathered investors to try to find oil. Capital was hard to come by.

On the 200-acre Foster farm, one struggling and almost cashless outfit had to trade a one-sixteenth interest for $80 and an old shotgun to continue drilling on its Sherman well.

Drilling along Oil Creek continued undiminished, but in September 1861 on the Funk farm, the Empire well began flowing a river of oil under its own pressure. They called it a “fountain well.” Some said it initially produced 2,000 barrels of oil a day. Other successful wells followed.

Back on the Foster farm lease, the Sherman well (saved earlier for $80 and a shotgun) in March 1862 was completed as the “best single strike of the year,” despite being “above all the other flowing wells” according to the Hornellsville Tribune. Leases became highly prized and, as historian Terence Daintith observed, “subleasing was also a money machine.”

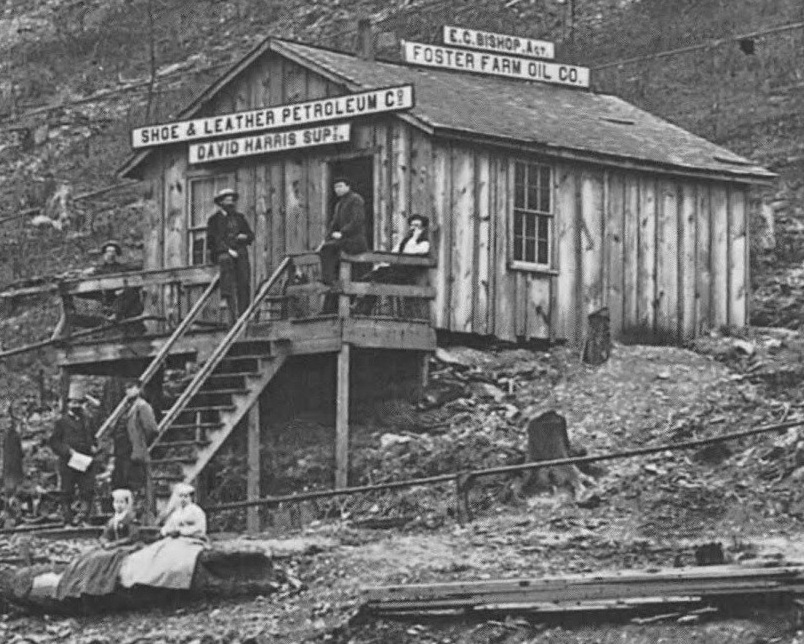

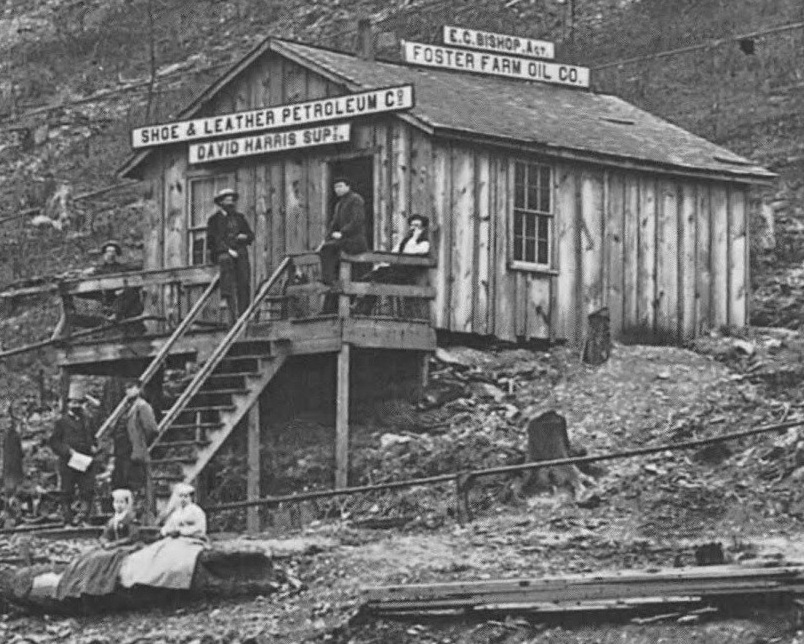

Oilfield offices of the Shoe & Leather Petroleum company, David Harris Supply Company, and the Foster Farm Oil Company, which drilled an 1866 well that produced 300 barrels of oil.

The Venango Citizen reported, “Territory along the river above and below Franklin has been changing hands at high figures, and preparations are being made for active work.”

Just four acres close to the Sherman well sold for $220,000 as venture capitalists, entrepreneurs, and speculators tried their luck in the newly created petroleum industry. The Foster Farm Oil Company and the Shoe & Leather Petroleum Company were among many corporations formed to exploit exploration opportunities.

Foster Farm Oil Company

Foster Farm Oil Company incorporated in February 1865. Based in Philadelphia and capitalized at $1.5 million, the company offered 150,000 shares to the public. “The Foster Farm is owned by a company of ten gentlemen, and is known as the Foster Farm Oil Company,” reported the The Titusville Morning Herald. E.C. Bishop (Elisa Chapman ) was principal owner as well as one time general agent, treasurer, and superintendent.

The new company secured acreage on the Foster farm that already had 12 wells pumping 100 barrels of oil a day. Foster leased acreage in small tracts to several new companies vying for closest proximity to known producers. Oil prices had always fluctuated wildly, but a standard 42-gallon barrel of crude oil sold in 1865 for about $6.50, including a Civil War excise tax of $1 per barrel.

Foster Farm Oil Company continued drilling and subleasing small tracts. In April 1866, it drilled a well producing 300 barrels of oil a day from 612 feet deep. Then a second well produced at 310 barrels, a third at 100, and another at 350 barrels of oil a day. In 1867, Foster Farm Oil Company sold 1,000 barrels of oil at $2.10 each.

All over the Pioneer Run hillside, wooden derricks with steam engines pumped away even as overproduction drained the oilfield. Margins disappeared and companies began to fail.

Foster Farm Oil Company’s fortunes faded, as did the value of its stock. In 1869, total U.S. oil production topped 4 million barrels and oversupply drove many out of business. After 10 years in the oil patch, Elisha C. Foster departed to enter the banking business in Connecticut.

By 1871, shares of Foster Farm Oil were being auctioned off along with other “Stocks, Loans, etc.” The following year, 5,000 shares of Foster Farm Oil Company were offered at 11 cents a share. Litigation began to overtake the failing company in 1873; it would continue long after the drilling boom had moved on, finally being settled by the Connecticut Superior Court in 1886.

Shoe & Leather Petroleum

Shoe & Leather Petroleum Company incorporated in New York City in March 1865 to join the Pennsylvania oil rush. The company initially capitalized at $400,000, later reduced to $160,000. “Until the spring of 1865, the Foster Farm, Pioneer Run and vicinity were considered dry territory. Through the exertions of Mr. David Harris of this city, the Shoe & Leather Petroleum was formed,” reported the Titusville Morning Herald.

The company leased six acres on the Foster farm, then subleased them into 11 smaller tracts – the kind sought by smaller, speculative operations. “Substantial leaseholders could milk their leases by subleasing small lots for large premiums and high royalties,” historian Daintith later noted. “Far more money could be made this way than by actual production.”

By 1867, Shoe & Leather Petroleum had five producing wells, on five different tracts, with five different operators, yielding about 350 barrels of oil a day. But frantic production at Pioneer Run and Oil Creek, compelled land owners above oil reserves to drill, “regardless of price or market demand, in order to prevent his neighbor from draining his reserves.”

This traditional “law of capture” rendered an oily landscape thick with derricks, according to local accounts.

Overproduction and waste depleted reservoir pressures. Wells were pumped dry. Triumph Hill, and Pithole and other examples reinforced the precedent of oil discovery leading to drilling boom, and then to inevitable bust. By 1902, United States Investor reported Shoe Leather & Petroleum Company had “disappeared” and concluded, “The supposition is that the company has gone out of existence.”

In 1904, Smythe’s Directory of Obsolete American Securities and Corporations described Shoe & Leather Petroleum, “Extinct. Stock worthless.”

The stories of exploration and production companies can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Cherry Run Valley: Plumer, Pithole, and Oil City, Pennsylvania (2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2000); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Early Wells of Oil Creek.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/early-wells-of-oil-creek. Last Updated: November 1, 2024. Original Published Date: December 22, 2018.

(2000); The Legend of Coal Oil Johnny

(2007); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.