by Bruce Wells | Mar 3, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Louisiana oil boom brings pipelines, refineries and competition.

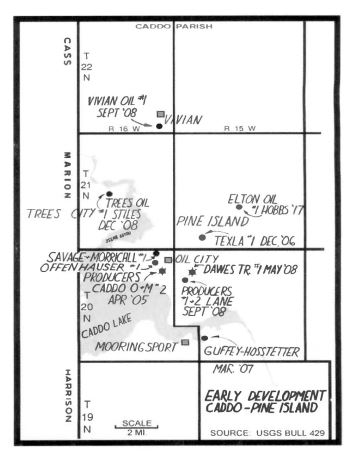

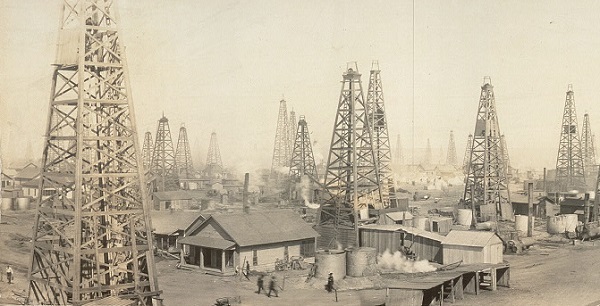

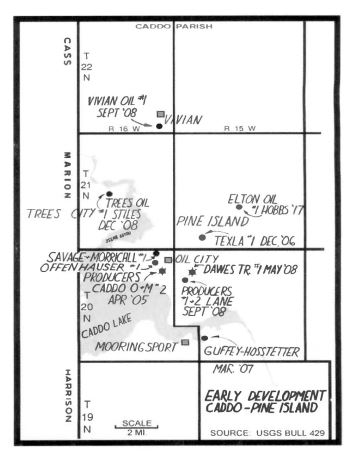

Claiborne Parish made headlines on January 12, 1919, when Consolidated Progressive Oil Company completed the discovery well for northern Louisiana’s prolific Homer oilfield. About 50 miles to the west, a 1905 oil discovery at Caddo-Pines near Shreveport had brought a rush of oil exploration to northern Louisiana.

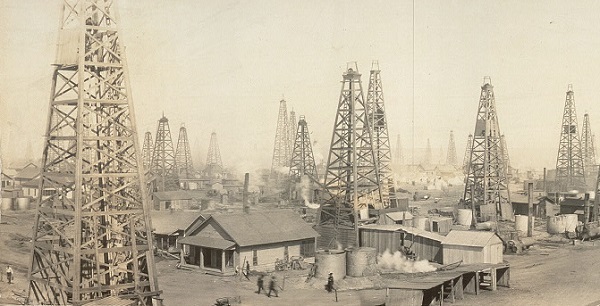

Caddo Lake drilling platforms – completed over water without a pier to shore – have been called America’s first true offshore oil wells. Exhibits at the state’s Oil City museum tell that story. Like Caddo-Pines, the Homer field was crowded with new companies within months after the discovery.

Petroleum production from the new field soon reached an aggregate of about 10,000 barrels of oil per day. Reporting from the Pennsylvania oil regions, Pittsburgh Press on September 21, 1919, proclaimed the “Homer Field is Sensation of Oil Industry.”

Detail from a panoramic “bird’s eye view” of the Homer oilfield circa 1920s. Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Superior Oil Works

Paramount Petroleum Company began when the leadership of another company operating in the Homer oilfield decided to expand operations. Superior Oil Works officers, including President George A. Todd of Oklahoma City; Secretary and Purchasing Agent H.H. Todd of Vivian, Louisiana; and Treasurer D.C. Richardson of Shreveport organized the Paramount Petroleum Company.

Superior Oil Works had been formed to build and operate a refinery close to the Homer field. Capitalized at $300,000 with common stock issued, the company began construction in Superior, Louisiana, but its officers were by then contemplating the much-expanded venture — the formation of Paramount Petroleum to integrate exploration, production, transportation and refining under one organization.

Once established, the new company absorbed Superior Oil Works and looked for potential leases near the Consolidated Progressive Oil Company’s discovery well. As construction of the Superior refinery progressed, purchasing agent H.H. Todd advertised that Paramount Petroleum was “in the market for oil refinery equipment, boilers, stills, pumps, and plant machinery, etc.”

Paramount Petroleum made a deal with Consolidated Progressive Oil in May 1919, securing one-half interest in more than 11,000 acres of both proven and unexplored territory in Claiborne Parish. The acreage was already producing about 40,000 barrels of oil, ensuring the refinery would be supplied.

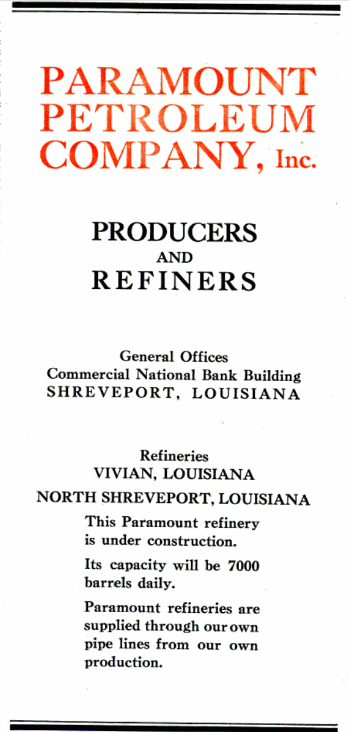

“A giant refining company has been organized recently in Shreveport to be known as the Paramount Petroleum Company,” noted the Oil Distribution News. The venture was capitalized at $10 million with half of its stock subscribed.

“Stock in this company has been consumed by the largest business and banking men of Shreveport,” added the Oil and Gas News. But the best news for investors was the headline: “Paramount Petroleum Gets 10,000 Barrel Well And Will Build Big Refinery.”

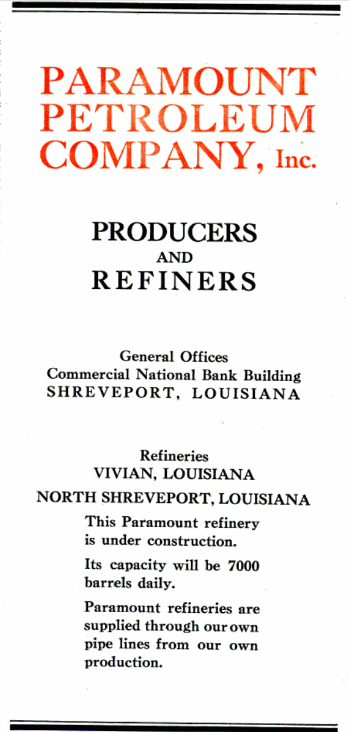

In March 1920, the Petroleum Age reported Paramount Petroleum “recently took over the under-construction Superior Oil Works refinery at Vivian [Superior], Louisiana, 23 miles north of Shreveport, to service Pine Island production.”

The publication added that another refinery was to be completed in north Shreveport in November 1920 “with a four-inch pipeline from the Homer field where Paramount Petroleum holds 4,700 acres.”

Paramount Petroleum Company’s newest refinery would be struggling by May 1921.

Within a month Paramount Petroleum was drilling in Claiborne Parish and shipping 400,600 barrels of oil a day. The company secured a $1 million mortgage from the Commercial National Bank of Shreveport and advertised, “Paramount refineries are supplied through our own pipelines from our own production.”

Paramount Petroleum in July 1920 completed the No. 5 Shaw well, which produced 500 barrels of oil a day from 2,090 feet deep in the Homer field. In August, the company’s No. 9 Shaw well become another 500-barrels-of-oil-a-day producer from a depth of 2,100 feet.

Anticipating more growth in oil production, Paramount Petroleum committed to an agreement for 300 tank cars from Standard Tank Car Company of St. Louis, Missouri.

“Not too bright”

“Paramount has just closed a deal for one half interest in 24 producing wells in the old Caddo field with 1,200 acres of proven territory on which many wells can yet be drilled,” reported the Petroleum Age in October 1920. “The production department of Paramount Petroleum is making splendid headway and with its large acreage, will no doubt greatly add to the earnings of the company.”

But the Petroleum Age reporter had got it wrong. By February 1921, Paramount Petroleum’s refinery at Superior was running at only about 50 percent capacity. Another trade publication reported the company’s prospects as “not too bright.”

Shipments from Paramount Petroleum’s Homer oilfield holdings dropped to just 168 barrels of oil a day. In May 1921 the struggling company leased its underused refinery and fleet of 390 tank cars to Lucky Six Oil Company for six months.

The Homer field attracted drillers from earlier discoveries at the nearby Caddo-Pines oilfields. Photo courtesy the Petroleum History Institute.

To the south, the Busey-Armstrong No. 1 oil gusher on January 10, 1921, had opened Arkansas’ El Dorado field and Lucky Six Oil Company had entered the scramble to exploit the new field’s huge production (578,000 barrels of oil in the month of May alone).

The oilfield discovery 15 miles north of the Louisiana border was the first Arkansas oil well. It attracted even more exploration and production companies to the region.

As competition intensified, Paramount Petroleum struggled to pay debts. It was unable to make a required $200,000 mortgage payment to Commercial National Bank of Shreveport in July 1921. The deal Paramount had struck with Consolidated Progressive Oil back in 1919 had become toxic.

The National Petroleum News reported on September 7, 1921, that Consolidated Progressive Oil was seeking a court-ordered receiver to take over Paramount Petroleum. The action was based on claims totaling $849,547 — and “averred acts jeopardizing the interests of creditors.” Among the allegations was “the effect that officials of the defendant concern have admitted in writing the company’s inability to meet present and maturing obligations.”

Paramount Petroleum’s epitaph was brief. “It is officially stated that this company is out of business,” reported Poor’s Cumulative Service in December 1921. “Its properties are to be sold by the sheriff December 24 and proceeds applied on the first Mortgage notes.”

The first Louisiana oil well had been drilled 17 years before the end of Paramount Petroleum. More stories about petroleum exploration and production companies trying to join drilling booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

______________________

Recommended Reading: Louisiana’s Oil Heritage, Images of America (2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright AOGHS © 2025

Citation Information – Article Title: “Paramount Petroleum Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL:httpshttps://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/paramount-petroleum-company. Last Updated: March 9, 2025. Original Published Date: August 15, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 2, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Three petroleum exploration companies risked everything on one well in their gamble to to find an Oregon oilfield.

The lure of petroleum wealth invited speculators practically since the first U.S. oil well of 1859 in Pennsylvania. Exploratory wells especially have remained a high-risk investment since almost nine out of ten of these “wildcat” wells fail to produce commercial amounts of oil.

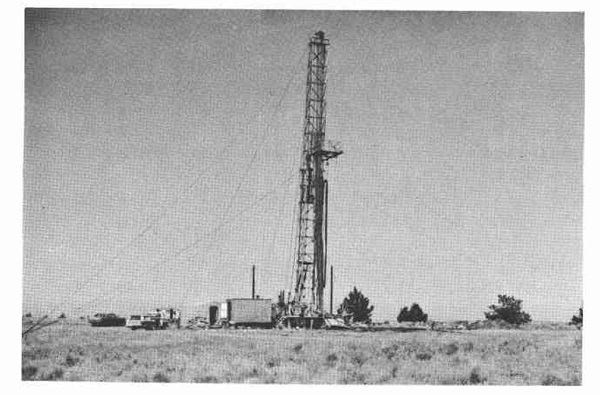

The Morrow No. 1 well, an ill-fated wildcat well first drilled in 1952 in Jefferson County, Oregon. Photo courtesy Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, “The Ore Bin,” Vol. 32, No.1, January 1970.

With under-capitalized operations turning to public sales of stock to raise money, many small ventures have been forced to bet everything on drilling a first successful well to have a chance at a second. Drilling a producing well can bring some wealth, but a “dry hole” brings bankruptcy.

And so it was in the 1950s on a remote hillside in Jefferson County, Oregon, where three companies searched for riches from the same well.

Northwestern Oils Inc.

The first of these three Oregon wildcatters, Northwestern Oils, incorporated in 1951 with $1 million capitalization in order to “carry on business of mining and drilling for oil.”

With offices in Reno, Nevada, in early 1952 Northwestern Oils began drilling a test well about eight miles southeast of Madras, Oregon. Using a cable-tool drilling rig (see Making Hole – Drilling Technology), drillers reached a depth of 3,300 feet on the Baycreek anticline before work was suspended because of “lost circulation troubles.”

Circulation troubles continued with the Morrow No. 1 well – also known as the Morrow Ranch well – in Jefferson County (Section 18, Township 12 South, range 15 East). By March 1956, with no money and no additional drilling possible, Northwestern Oils’ assets were “seized for non-payment of delinquent internal revenue taxes due from the corporation” and auctioned off at the Jefferson County courthouse.

Central Oils Inc.

Central Oils (Seattle) also was formed in 1956. With plans to join the other rare Oregon wildcatters, the company registered with the Security and Exchange Commission on July 30, 1958. It sought to sell one million shares of stock to the public at 10 cents a share. Proceeds would finance leasing and drilling, just like Northwestern Oils.

Central Oils received a permit to deepen Northwestern Oils’ old Morrow Ranch well in 1966 and planned to continue drilling with a cable-tool rig. Nothing happened.

“Commencement of this venture has been delayed until the spring of 1967,” one newspaper reported. But Central Oils had run afoul of the SEC. Oregon regulators recorded the well abandoned as of September 12, 1967, and Central Oils “out of business; no assets.”

Robert F. Harrison

In May 1968, Robert F. Harrison and his associates took over the same well — this time with plans to deepen it to more than 5,000 feet. But two years later the drilling effort was still stuck at a depth of 3,300 feet. Desperate, Harrison tried to clear the borehole by applying technologies for Fishing in Petroleum Wells.

On February 2, 1971, an intra-office report noted that R.F. Harrison “will abandon as soon as weather permits,” never having exceeded the original Northwestern Oils total depth of 3,300 feet. It would be a dry hole.

Harrison finally plugged and abandoned the Morrow No. 1 well as of October 12, 1971. Oregon’s Department of Geology and Mineral Industries has identified the stubborn nonproducer as well number 36-031-00003. There has never been a successful oil well drilled in Oregon.

America’s first dry hole was drilled in 1859 by John Grandin of Pennsylvania – near and just a few days after the first commercial discovery. In 2014, U.S. oil wells produced more than 8.7 million barrels of oil every day, according to the Energy Information Administration.

The stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

______________________

Recommended Reading: Oil on the Brain: Petroleum’s Long, Strange Trip to Your Tank (2008);The Greatest Gamblers: The Epic of American Oil Exploration

(2008);The Greatest Gamblers: The Epic of American Oil Exploration (1979).

(1979).

Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oregon Wildcatters.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/oregon-wildcatters. Last Updated: February 26, 2025. Original Published Date: January 29, 2016.

by Bruce Wells | May 15, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

Widely publicized drilling booms attracted investors seeking “black gold” riches — real or imagined.

Exaggerated, questionable, and sometimes fraudulent claims by shady business ventures seeking investors grew in the years following World War I. As the Great Depression approached, many states passed “blue sky laws” to regulate securities sales and protect the public from fraud.

It would take an act of Congress in 1934 to stop skilled business hucksters from taking advantage of unwary investors seeking often fictional profits. Federal lawmakers established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to help rein in exaggerated claims found in newspaper advertisements, mail solicitations, and other stock promotions.

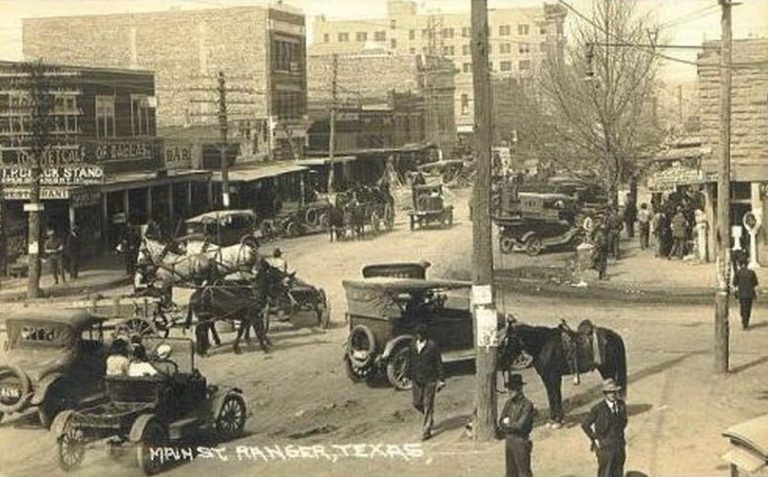

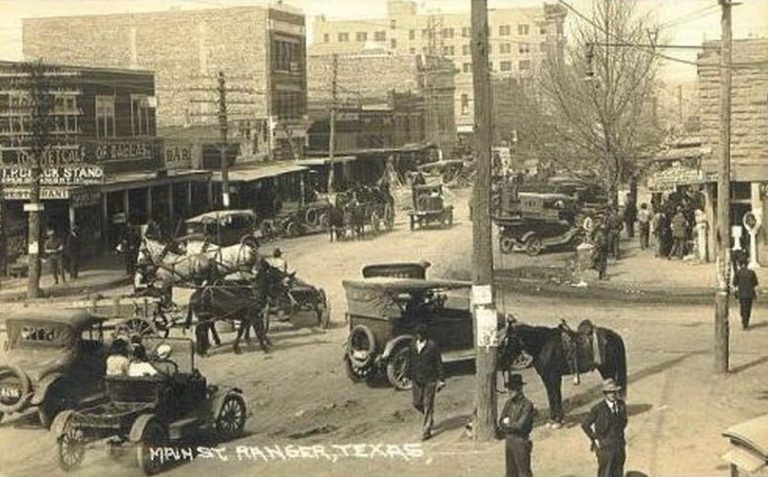

Widely publicized giant oilfield discoveries at Burkburnett, Texas, in 1918 (above) and nearby “Roaring Ranger” one year earlier led to many inexperienced exploration ventures and exaggerated promotions. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Since the U.S. petroleum industry’s earliest booms and busts in Pennsylvania following the Civil War, the need for dependable information and early financial centers — petroleum exchanges — led to a new profession — the oil scout.

As demand for refined kerosene for lamps grew, the search for new oilfields moved to mid-continent. Thousands of exploration and production companies were established. Most drilled dry holes. When wildcat wells (remote) revealed giant oil and natural fields in Texas and Oklahoma, a new generation of business financing hucksters took advantage.

The J.H. McCleskey No. 1 discovery well of October 1917 created a massive oil boom at Ranger and across Eastland County, Texas. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Giant oilfield discoveries in North Texas made headlines, leading to the hundreds of new exploration companies (see Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?). Many began by seeking capital from local investors, often banks, doctors, and civic leaders. Financial swindlers saw opportunities to take advantage of oilfield discoveries and the resulting oil fever.

Newspapers nationwide reported wells with geysers of oil at Electra (1911), Ranger (1917), and the “World’s Wonder Oilfield” of Boom Town Burkburnett (1918). Publicity about these oil booms rekindled enthusiasm for Texas petroleum riches not seen since the giant oilfield discovery at Spindletop Hill in 1901, the famous “Lucas Gusher.”

Sudden, unexpected “black gold” or “Texas tea” wealth brought prosperity to struggling farming communities. Thanks to the Ranger oilfield, Eastland County’s Merriman Baptist Church (and graveyard) was once declared the richest church in America.

Black Gold Dreams

Criminals specializing in financial deception joined the influx of drilling contractors, workers, equipment suppliers, lease brokers, and associated oilfield service companies. In part to combat fraud in North Texas, the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG), founded in 1917, American Petroleum Institute (API), founded in 1919, and other industry associations organized.

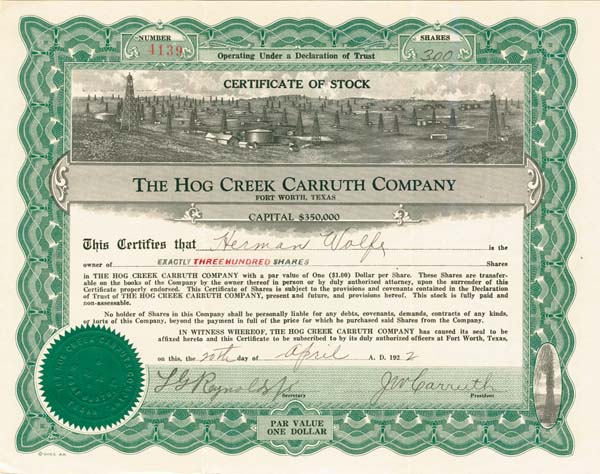

With so many oil boom-inspired companies forming so quickly, the rapid printing of eye-catching but boiler-plate stock certificates often occurred (see Oil Prospects Inc. for one of the most common certificate vignettes).

In a rush to find investors, quickly formed exploration companies ended up using the same oilfield scene for stock certificates. It might have saved time and money by choosing a printer’s common vignette.

Already iconic U.S. boom towns and busts (see the remarkable 1865 rise and fall of Pithole, Pennsylvania) would help launch major companies like Marathon and Texaco, as did the first California oil wells. New petroleum discoveries attracted experienced companies — and many more inexperienced exploration and production ventures that aggressively sought leases, equipment and men, and investors.

However, with little knowledge of the new science of petroleum geology and drilling technologies, few of newly formed companies would find oil. Most did not survive long in the highly competitive oilfields.

Crowding too many wells on leases and a lack of infrastructure for storing and transporting oil harmed the environment. Many companies learned from hard experience, but more went bankrupt without ever finding oil.

Competing exploration companies, lacking petroleum engineers and efficient production technologies, often overproduced geological formations. Unchecked drilling and oversupply in the oil market led prices to collapse as low as 15 cents per 42-gallon oil barrel in the giant East Texas oilfield of the 1930s.

Huckster of Hog Creek

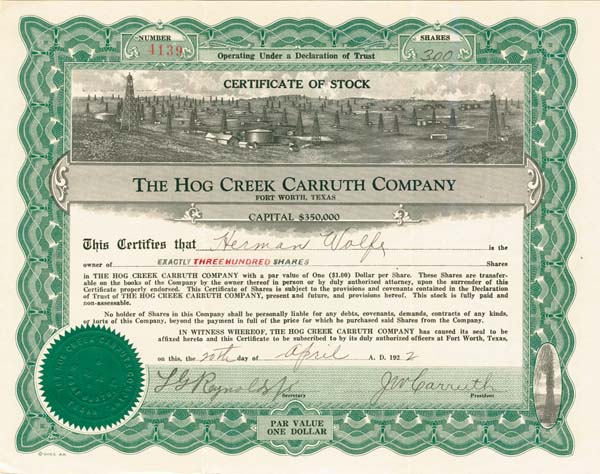

The lure black gold also attracted skilled confidence men who could create oil companies on paper. J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth was among the most notorious.

Financial World in 1912 described “Hog Creek” Carruth as a con man who made a fortune selling worthless oil stocks. The magazine also cited the far better known infamous explorer Dr. Frederick Cook (learn more in Arctic Explorer turned Oil Promoter).

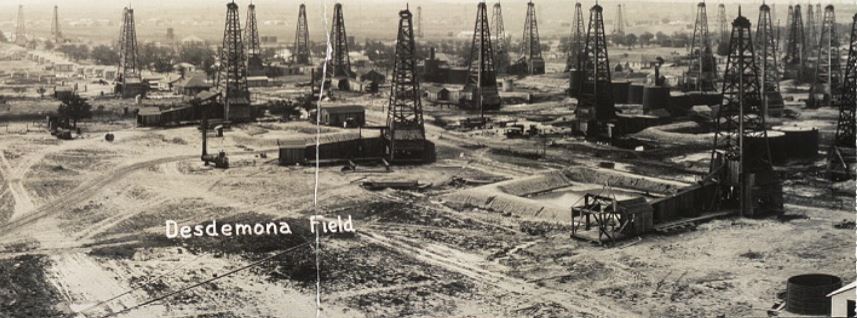

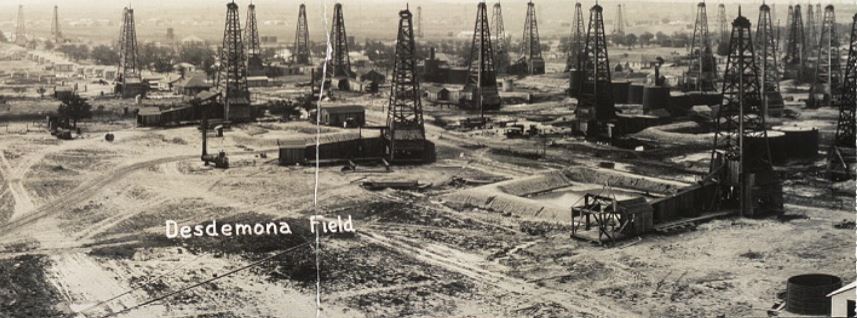

In September 1918 a discovery well near Desdemona blew in after reaching a depth of 2,960 feet, initially producing 2,000 barrels of oil a day. “Unlike Ranger, Desdemona was a small operator’s field. Production reached a peak of 7,375,825 barrels in 1919, and then dropped sharply, chiefly because of over drilling,” according to the Handbook of Texas Online.

“Hog Creek” Carruth proclaimed himself to be the discoverer of the Desdemona oilfield (he was not). He advertised expansively to sell worthless stocks inflated by his phony reputation.

Pilgrim Oil Company

Pilgrim Oil Company formed as a common law trust estate (unincorporated business managed by trustees) in Fort Worth, Texas, on December 20, 1920. The company’s trustees included George M. Richardson and Warren H. Hollister. and was capitalized at $1 million with 100,000 shares offered at par value of $10.

The petroleum company, another fraudulent enterprise of J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth, would be his last.

J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth falsely claimed to have discovered the Desdemona, oilfield, along Hogg Creek. Detail from circa 1919 panoramic photo courtesy Library of Congress.

The oilfield along Hog Creek had been discovered in 1918, just one year after the famous Ranger well. This new field at Desdemona (once called Hog Town) attracted the usual rush of new exploration companies, many with little or no drilling experience.

Among the Eastland County startups, a wily financial conman’s Hog Creek Carruth Oil Company profited by colorful stock sale advertisements to attract investors.

The skillfully exaggerated promotions of Carruth prompted one contemporary writer to admire the crook’s audacity. “Any reader who cannot get a thrill out of Carruth’s highly colored advertising literature is indeed phlegmatic,” the observer declared.

But harm to many small, unwary investors was real. Most of the stock sales’ dollars went into Carruth’s pockets instead of his companies. Even the failure of his oil companies became part of his schemes.

Hogg Oil + Hog Creek Carruth Oil

Carruth merged two of his insolvent petroleum companies — Hogg Oil Company and Hogg Creek Carruth Oil Company — to create the Pilgrim Oil Company. His latest venture attracted some skeptical attention from financial magazine editors. The Pilgrim Oil Company, “makes a business of gathering in defunct oil companies,” reported Financial World.

As part of his connived merger game plan, stockholders of the two bankrupt Carruth oil ventures had to buy an additional 25 percent of Pilgrim Oil Company shares (in cash) or lose their investments entirely. Carruth used this money to pay dividends, thereby luring more buyers into his petroleum company Ponzi scheme.

Financial World noted, “This is a promoter’s way of reloading old stockholders with additional $25 worth of stock for every $100 they hold in a defunct company.”

J.W. Carruth merged his fraudulent Hogg Creek Carruth Oil with his other fraudulent oil company to create Pilgrim Oil company, a Ponzi scheme using investors’ purchase money to pay dividends and lure more buyers.

In 1923, a federal court indicted J.W. “Hog Creek” Carruth for mail fraud. Also indicted were Pilgrim Oil Company trustees Richardson and Hollister. Eighty-nine other shady characters also were named in a sweeping indictment aimed at stock hucksters.

U.S. Penitentiary, Leavenworth

Federal prosecutors reviewed financial harm to innocent Pilgrim Oil Company shareholders, who pleaded to the court for justice.

“False, fraudulent, and untrue representations were made for the purpose of inducing plaintiffs to buy the said stock of the said two companies, and for the purpose of cheating, swindling, and defrauding plaintiffs out of their money, and did cheat, swindle, and defraud plaintiffs out of their said money,” the attorneys declared.

“That in 1922, and for a long time prior and subsequent thereto, defendant was engaged in handling and selling oil stock certificates and owned and controlled interests in various oil companies and concerns in this state,” the prosecutors added. Dozens of convictions followed.

Carruth earned a one-year sentence in Leavenworth, Kansas. He joined the federal penitentiary’s oil-scheme alumni Dr. Frederick Cook, the fraudulent Arctic explorer turned oil well promoter. Pilgrim Oil Company and the other Carruth company shareholders were left with stock certificates of no value, except perhaps as a family stories and heirlooms.

Convicted felon “Hog Creek” Carruth, who died in obscurity in 1932, should not be confused with former Texas Governor James S. “Big Jim” Hogg, who helped discover the important West Columbia oilfield in 1917 — learn more in Governor Hogg’s Texas Oil Wells.

New Jersey Oilfield?

A West Coast newspaper in 1916 reported on a rare attempt to find an East Coast oilfield. “Lewis Steelman, the man who has been prospecting for oil near Millville, N.J., for some time, has begun active work to locate an oil well and he confidently expects to strike the fluid,” reported California’s Santa Ana Register.

In New Jersey, the recently established Steelman Realty Gas & Oil Company was selling stock buttressed by the declarations of Dr. H. J. von Hagen, who company executives cited as “one of the world’s greatest living geologists and petroleum engineers.” Learn more in Fake New Jersey Oil Well.

More articles about U.S. exploration and production companies and links for further research can be found in Oil Stock Certificates.

_______________________

Recommended Reading (October 9): The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1936); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS annual supporter. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Exploiting North Texas Oil Fever.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/pilgrim-oil-company-exploiting-oil-fever. Last Updated: May 4, 2024. Original Published Date: September 9, 2021.

.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 29, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

Although successful oil wells had been drilled as early as 1901, oil fever arrived in Montana with the October 1915 discovery of the Elk Basin oilfield in Carbon County.

More discoveries came at the Cat Creek oilfield in 1920 and in the Kevin-Sunburst oilfield of 1922, both of which motivated businessmen in Miles City to form the Montana Bell Oil & Gas Company. They filed to do business in the state on March 8, 1924, but their timing was terrible.

Montana’s first oil well was drilled in 1901 in the Kintla Lake area that’s now part of Glacier National Park. Photo courtesy Daily Inter Lake, Kalispell, Montana.

In the last few months of 1924 alone, a financial crisis described by Montana’s superintendent of banks as a “veritable nightmare” closed 191 banks.

Bankrupt in Montana

Between 1921 and 1926, no state had more bankruptcies than Montana. Newspapers reported in 1924 reported “the tremulous activity” of Montana Belle Oil that “may be expected in this country within the year, unless present plans halted.”

Nonetheless, Montana Belle Oil & Gas was able to secure a mineral lease from Adolph F. Loesch west of Miles City in April 1926. The company selected a drilling site for its first well in typically foreboding southeast Montana (see Public Land Survey System, Northeast Quarter of Section 28, Township 8 North, Range 45 East).

Drilling the wildcat well during hard financial times and in a remote location slowed progress. Legal issues also troubled the company, according to reports in the Billings Gazette.

“With the settlement of differences arising without recourse to the courts, the officers of the Montana Belle Oil & Gas company are preparing to proceed,” the newspaper noted in January 1928.

“Drilling in the Montana Belle Oil and Gas company well, located about twelve miles west of this city is proceeding 24 hours a day,” the reporter added.

Using dated cable-tool drilling technology, the company reached a depth of 1,035 feet. The Billings Gazette reported the company’s objective was a depth of 1,750 feet, “in accordance with the report of the geologist who has made a survey and examination of the earth strata, and at which it is expected that results will follow. Gas is also in evidence in the hole.”

Investors and stockholders were encouraged that the well was “showing some light oil though not in commercial quantities.” The drilling continued into deeper formations. On October 24, 1929 — “Black Thursday” — the U.S. stock market crashed, launching the Great Depression.

In December 1929, five years after incorporating, Montana Belle Oil and Gas Company’s only oil well shut down for the winter. It reportedly had reach the impressive depth of 4,562 feet, but drilling never resumed. Montana Belle Oil and Gas Company failed in 1930, as did Miles City’s oil refinery and many other oilfield businesses.

The first Montana oil well was drilled in 1901 in the Kintla Lake area, later part of Glacier National Park. More about the state’s petroleum history can be found in the 2011 article “Montana’s first oil well was drilled at Kintla Lake in 1901.”

_______________________

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Montana Belle Oil & Gas Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/montana-belle-oil-amp-gas-company. Last Updated: February 29, 2024. Original Published Date: April 13, 2022.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 1, 2024 | Petroleum Companies

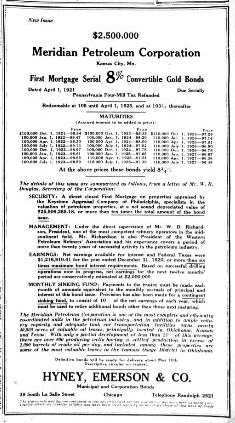

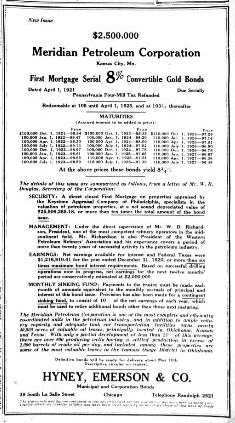

An experienced independent oil producer, W.D. Richardson orchestrated the merger of his own company, Lake Park Refining (incorporated 1918), with Dunn Petroleum and Davenport Petroleum to form Meridian Petroleum Company in September 1920.

Merger terms dictated one share of Dunn Petroleum for two shares Meridian Petroleum; one share of Lake Park Refining for two shares Meridian Petroleum; and one share of Davenport Petroleum Co. for 20 shares Meridian Petroleum.

The combined organization held assets valued at about $13 million, including refineries in Oklahoma: Okmulgee (3,500 barrel), Ponca City (2,500 barrel), and Hominy (1,500 barrel). There also were producing wells in Oklahoma, Kansas and Texas, as well as “promising acreage” in Wyoming.

The combined organization held assets valued at about $13 million, including refineries in Oklahoma: Okmulgee (3,500 barrel), Ponca City (2,500 barrel), and Hominy (1,500 barrel). There also were producing wells in Oklahoma, Kansas and Texas, as well as “promising acreage” in Wyoming.

With offices in Kansas City, Missouri, Delaware-chartered Meridian Petroleum was capitalized at $25 million. By the end of 1920, the new company reported a net profit of $1,076,828. At the company’s annual meeting in April 1921, at least 3,000 Meridian Petroleum stockholders re-elected W.D. Richardson and the company’s officers.

“Rarely have stockholders made so plain their confidence in the management of an oil company,” noted The Oil & Gas News reported. At the same meeting, stockholders approved the issue of $2.5 million dollars in “first mortgage bonds to be used in retiring present outstanding indebtedness and to give the company additional working capital.”

Trade publications carried advertisements for Meridian Petroleum products such as “No. 1100 Straight Run Auto Oil” and “No. 22-600 S. R. Cylinder Stock (Light Green).” These and other lubricants were promoted with the Meridian motto, “The Line that Circles the World.”

But all was not well. The Oklahoma refineries depended upon crude oil deliveries, which were declining. Throughout 1921, only one of Meridian’s Petroleum’s three refineries operated at all, and it at half capacity.

The first official Oklahoma oil well was completed in 1897 at Bartlesville. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Oil production from Meridian Petroleum’s own leases proved insufficient, although in July 1921, Oildom reported a hopeful development.

“The company’s big well in the Hominy district of Osage county, Oklahoma, which came in at 10,000 barrels and ceased flowing after several days, due to a caved hole, was put in commission again and was reported making 3,000 barrels natural (flow),” the publication noted.

A report in the American Investor valued the company’s stock at about 13 cents a share on the New York Curb Market in December 1921, down from a high of 22 cents a share for the year and far less than the original offering at $2 per share.

On April 1, 1922, Meridian Petroleum defaulted on a $100,000 debt and in June, U.S. District Court appointed a receiver as the $2.5 million mortgage approved by stockholders a year earlier went into foreclosure. The company also carried unsecured debt of $600,000 and never paid a dividend.

Despite predictions of a reorganization, by 1927 Meridian Petroleum was gone for good. W.D. Richardson quickly went on to form the Richardson Refining Company, capitalized at $250,000 in November 1922.

The stories of exploration and production companies joining petroleum booms (and avoiding busts) can be found updated in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything? The Library of Congress offers further research help at Business History: A Resource Guide.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Meridian Petroleum Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/meridian-petroleum-company. Last Updated: February 14, 2024. Original Published Date: January 29, 2016.

(2012); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

The combined organization held assets valued at about $13 million, including refineries in Oklahoma: Okmulgee (3,500 barrel), Ponca City (2,500 barrel), and Hominy (1,500 barrel). There also were producing wells in Oklahoma, Kansas and Texas, as well as “promising acreage” in Wyoming.

The combined organization held assets valued at about $13 million, including refineries in Oklahoma: Okmulgee (3,500 barrel), Ponca City (2,500 barrel), and Hominy (1,500 barrel). There also were producing wells in Oklahoma, Kansas and Texas, as well as “promising acreage” in Wyoming.