by Bruce Wells | Mar 3, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

March 3, 1879 – United States Geological Survey established –

President Rutherford B. Hayes signed legislation creating the United States Geological Survey (USGS) within the Department of the Interior. The legislation resulted from a report by the National Academy of Sciences, which had been asked by Congress to provide a plan for surveying the country.

Original logo for the U.S. Geological Survey and the current one. The motto “science for a changing world” was added in 1997.

The new agency’s mission included “classification of the public lands, and examination of the geological structure, mineral resources, and products of the national domain,” according to USGS, which since 1974 has been headquartered on a 105-acre site in Reston, Virginia. USGS maintains the world’s largest library collection dedicated to earth and natural sciences, including more than one million books, 600,000 maps, and 500,000 photographs.

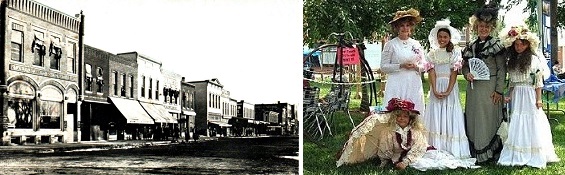

March 3, 1886 – Natural Gas brings light to Paola, Kansas

Paola became the first town in Kansas to use natural gas commercially for illumination. To promote its natural gas resources and attract businesses from nearby Kansas City, civic leaders erected four flambeaux arches in the town square. Pipes were laid for other illuminated displays.

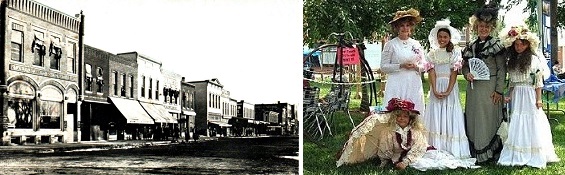

“Pearl Street Looking South, Paola, Kansas” is among images preserved by the Miami County Kansas Historical Society & Museum. An annual Paola Roots Festival began in 1990.

“Paola was lighted with Gas,” proclaimed an exhibit at the Miami County Historical Museum. “The pipeline was completed from the Westfall farm to the square and a grand illumination was held.” By the end of 1887, several Kansas flour mills were fueled by natural gas. Paola’s gas wells would run dry, but more mid-continent oil discoveries would follow

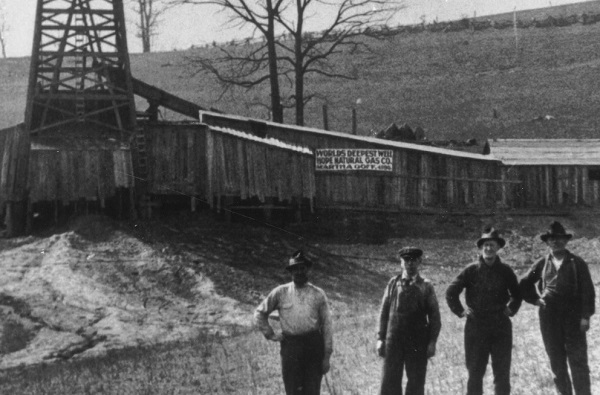

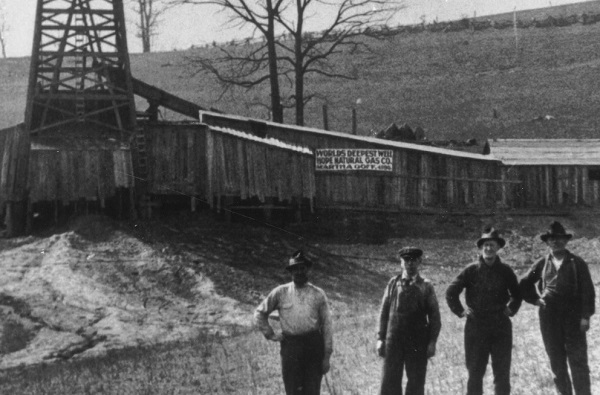

March 4, 1918 – West Virginia Well sets World Depth Record

Hope Natural Gas Company completed an oil well at a depth of 7,386 feet on the Martha Goff farm in Harrison County, West Virginia. The cable-tool well became the world’s deepest until surpassed by a 1919 well in nearby Marion County. The previous world record had been a well in Germany at 7,345 feet.

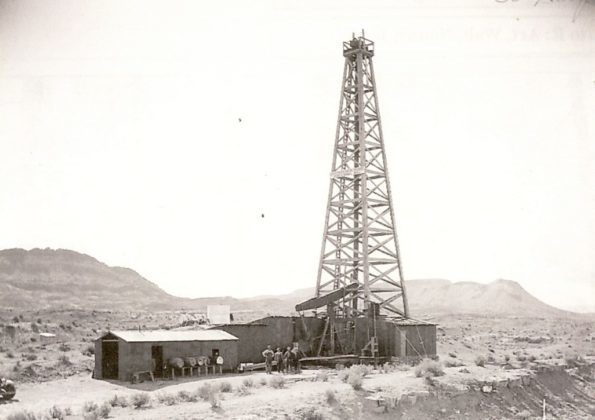

Drilled with cable-tools near Clarksburg, this 1918 West Virginia well was the world’s deepest until one drilled in a neighboring county. Photo courtesy West Virginia Oil and Natural Gas Association.

In 1953, the New York State Natural Gas Corporation claimed the world’s deepest cable-tool well at a depth of 11,145 feet at Van Etten, New York. A rotary rig depth record was set in 1974 by the Bertha Rogers No. 1 well at 31,441 feet, and a Soviet Union experimental well in 1989 reached 40,230 feet — the current world record.

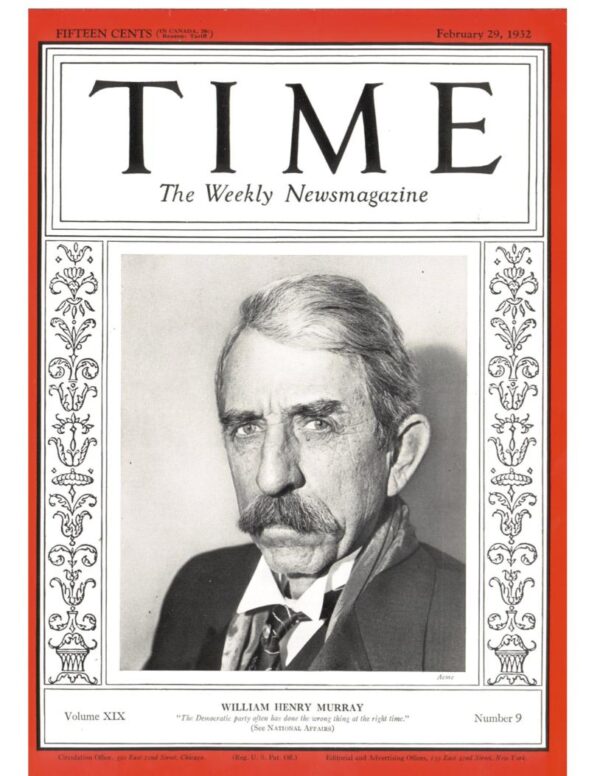

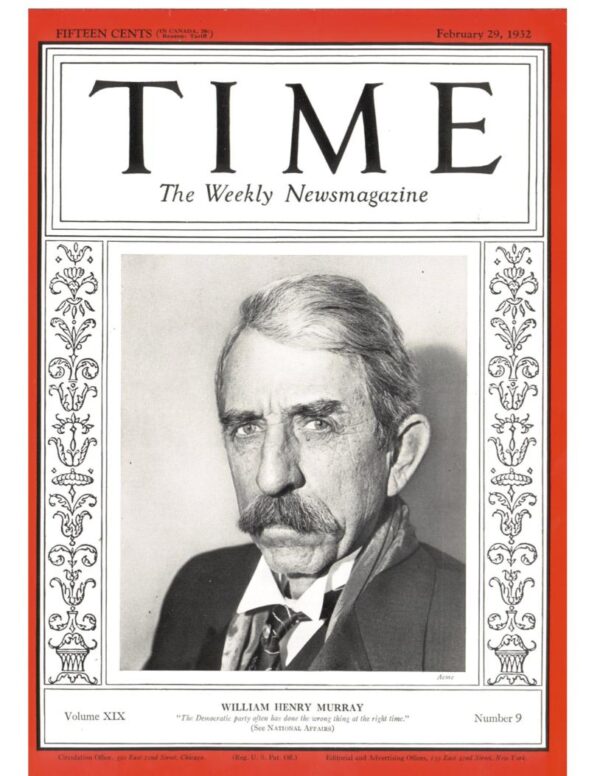

March 4, 1933 – Oklahoma City Oilfield under Martial Law

Oklahoma Governor William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray declared martial law to enforce his regulations strictly limiting production in the Oklahoma City oilfield, discovered in December 1928. Two years earlier, Murray had called a meeting of fellow governors from Texas, Kansas and New Mexico to create an Oil States Advisory Committee, “to study the present distressed condition of the petroleum industry.”

William “Alfalfa Bill” Murray in 1932.

Elected in 1930, the controversial politician was called “Alfalfa Bill” because of speeches urging farmers to plant alfalfa to restore nitrogen to the soil. By the end of his administration, Murray had called out the National Guard 47 times and declared martial law more than 30 times. He was succeeded as Oklahoma governor by E.W. Marland in 1935.

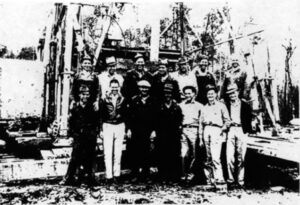

March 4, 1938 – Giant Oilfield discovery in Arkansas

The Kerr-Lynn Oil Company (a Kerr-McGee predecessor) completed its Barnett No. 1 well east of Magnolia, Arkansas, discovering the giant Magnolia oilfield, which would become the largest producing field (in volume) during the early years of World War II, helping to fuel the American war effort.

Crew members stand in front of their 1938 giant oilfield discovery well at Magnolia, Arkansas. Photo courtesy W.B. “Buzz” Sawyer.

The southern Arkansas gusher launched a Columbia County oil boom similar to Union County’s Busey-Armstrong No. 1 well southwest of El Dorado in January 1921 (see First Arkansas Oil Wells).

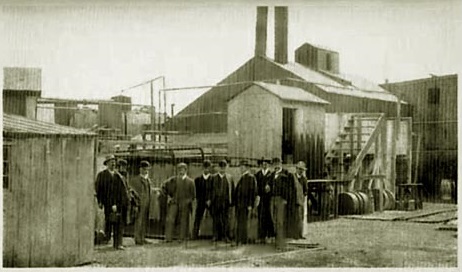

March 5, 1895 – First Wyoming Refinery produces Lubricants

Near the Chicago & North Western railroad tracks in Casper, Civil War veteran Philip “Mark” Shannon and his Pennsylvania investors opened Wyoming’s first refinery. It could produce 100 barrels a day of 15 different grades of lubricant, from “light cylinder oil” to heavy grease. Shannon and his associates incorporated as Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Company.

The original Casper oil refinery in Wyoming, circa 1895. Photo courtesy Wyoming Tales and Trails.

By 1904, Shannon’s company owned 14 wells in the Salt Creek field, about 45 miles from the company’s refinery (two days by wagon). Each well produced up to 40 barrels of oil per day, but transportation costs meant Wyoming oil could not compete for eastern markets. The state’s first petroleum boom began in 1908 with Salt Creek’s “Big Dutch” well.

Learn more in First Wyoming Oil Wells.

March 6, 1935 – Search for First Utah Oil proves Deadly

More than a decade before Utah’s first commercial oil wells, residents of St. George had hoped the “shooting” of a well drilled by Arrowhead Petroleum Company would bring black gold prosperity. A crowd had gathered to watch as workers prepared six, 10-foot-long explosive canisters to fracture the 3,200-foot-deep Escalante No. 1 well.

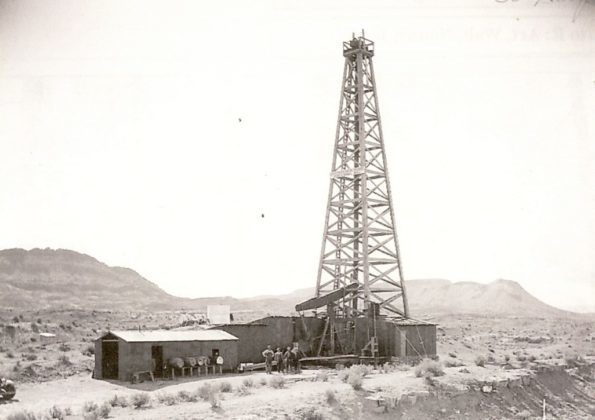

The Escalante well heralded new prosperity for residents of nearby St. George, Utah, in 1935 — until an attempt to shoot the well went wrong and canisters of TNT and nitroglycerin exploded. Photo courtesy Washington County Historical Society.

An explosion occurred as the torpedoes, “each loaded with nitroglycerin and TNT and hanging from the derrick,” were being lowered into the well. Ten people died from the detonations, which “sent a shaft of fire into the night that was seen as far as 18 miles away.”

The 1935 accident has remained the worst oil-related disaster in Utah, according to The Escalante Well Incident, a 2007 historical account.

March 6, 1981 — Shale Revolution begins in North Texas

Mitchell Energy and Development Corporation drilled its C.W. Slay No. 1 well, the first commercial natural gas well of the Barnett shale formation. Over the next four years, the vertical well in North Texas produced nearly a billion cubic feet of gas, but it would take almost two decades to perfect cost-effective shale fracturing methods combined with horizontal drilling.

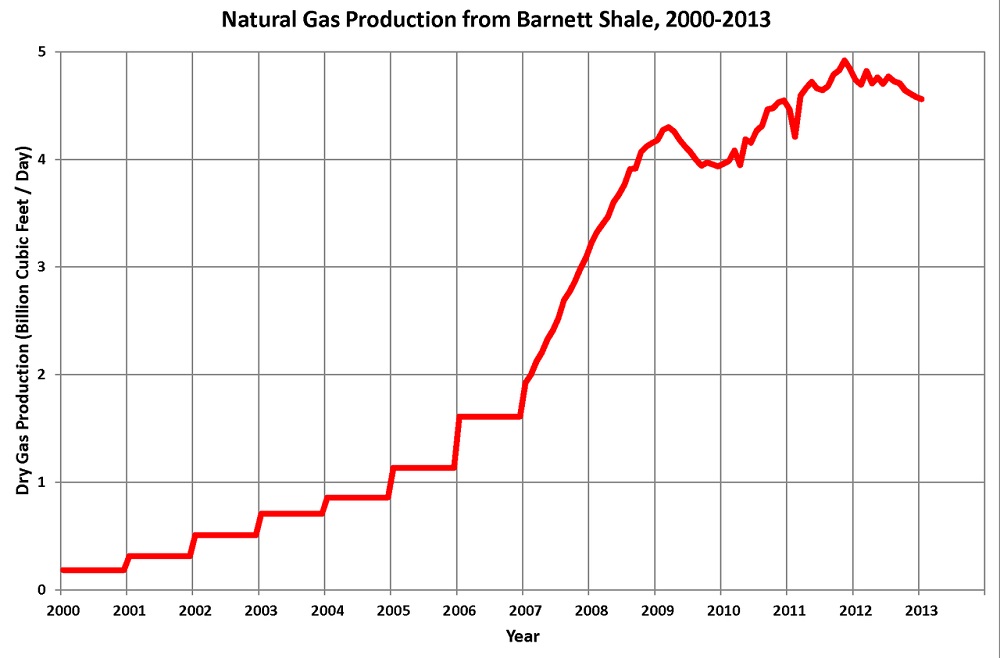

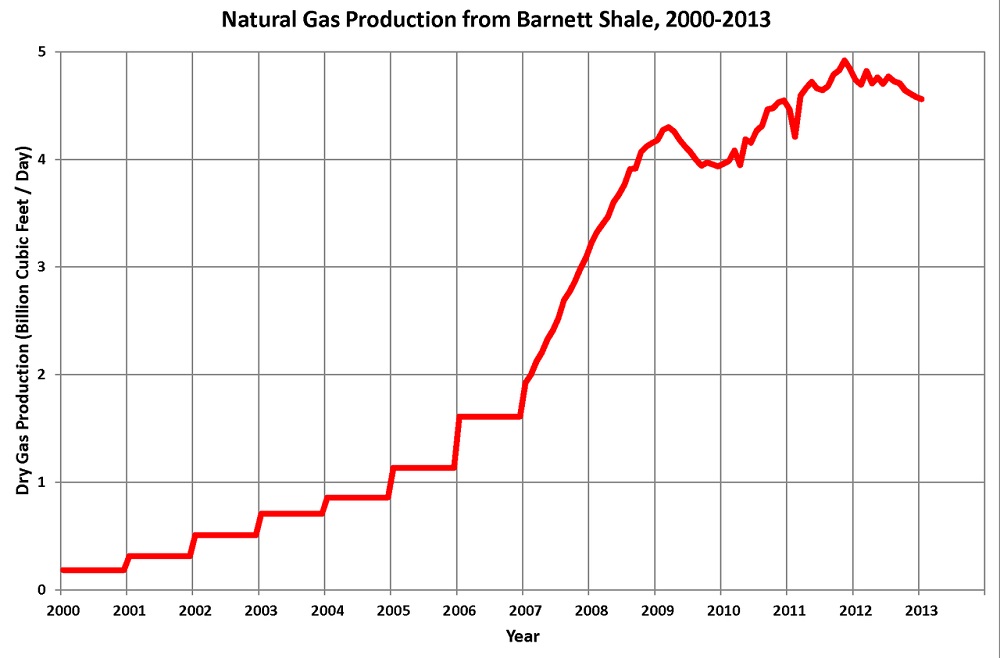

Production from the Barnett shale formation extends from Dallas west and south, covering 5,000 square miles, according to the Texas Railroad Commission. Chart courtesy Dan Plazak.

Mitchell Energy’s 7,500-foot-deep well and others in Wise County helped evaluate seismic and fracturing data to understand deep shale structures. “The C.W. Slay No. 1 and the subsequent wells drilled into the Barnett formation laid the foundation for the shale revolution, proving that natural gas could be extracted from the dense, black rock thousands of feet underground,” the Dallas Morning News later declared.

By the end of 2012, with almost 14,000 wells drilled in the largest gas field in Texas, production started to decline, but the Barnett field still accounted for 6.1 percent of Texas natural gas production and 1.8 percent of the U.S. supply, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

March 7, 1902 – Oil discovered at Sour Lake, Texas

Adding to the giant oilfields of Texas, the Sour Lake field was discovered about 20 miles west of the world-famous Spindletop gusher of January 1901. The spa town of Sour Lake quickly became a boom town where major oil companies, including Texaco, got their start.

“The resort town of Sour Lake, 20 miles northwest of Beaumont, was transformed into an oil boom town when a gusher was hit in 1902,” notes the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

Originally settled in 1835 and called Sour Lake Springs because of its “sulphureus spring water” known for healing, the sulfur wells attracted many exploration companies. Some petroleum geologists predicted a Sour Lake salt dome formation similar to that revealed by Pattillo Higgins, the Prophet of Spindletop.

Sour Lake’s 1902 discovery well was the second attempt of the Great Western Company. The well, drilled “north of the old hotel building,” penetrated 40 feet of oil sands before reaching a total depth of about 700 feet. The Hardin County’s salt dome oilfield yielded almost nine million barrels of oil by 1903, when the Texas Company made its first major oil find at Sour Lake.

Learn more in Sour Lake produces Texaco.

March 7, 2007 – National Artificial Reef Plan updated

The National Marine Fisheries Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), approved a comprehensive update of the 1985 National Artificial Reef Plan, popularly known as the “rigs to reefs” program.

A typical platform provides almost three acres of feeding habitat for thousands of species. Photo courtesy U.S. Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

The agency worked with interstate marine commissions and state artificial reef programs, “to promote and facilitate responsible and effective artificial reef use based on the best scientific information available.” The revised National Artificial Reef Plan included guidelines for converting old platforms into reefs. A typical four-leg structure provides up to three acres of habitat for hundreds of marine species.

“As of December 2021, 573 platforms previously installed on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf have been reefed in the Gulf of Mexico,” according to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

Learn more in Rigs to Reefs.

March 9, 1930 – Prototype Oil Tanker is Electrically Welded

The world’s first electrically welded commercial vessel, the Texas Company (later Texaco) tanker M/S Carolinian, was completed in Charleston, South Carolina. The World War I shipbuilding boom encouraged new electric welding technologies. The oil company’s 226-ton vessel was a prototype designed by naval architect Richard Smith.

Construction of M/S Carolinian began in 1929. The M/S designation meant it used an internal combustion engine. Photo courtesy Z.P. Liollio.

The tanker — the first electrically welded ship — eliminated the need for about 85,000 pounds of rivets, according to a 2017 article for the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH). Success of the prototype led to “the standard of welded hulls and internal combustion engines would become universal in construction of new vessels.”

March 9, 1959 – Barbie is a Petroleum Doll

Mattel revealed the Barbie Doll at the American Toy Fair in New York City. More than one billion “dolls in the Barbie family” have been sold since. Eleven inches tall, Barbie owes her existence to petroleum products and the science of polymerization, including several plastic acronyms: ABS, EVA, PBT, and PVC.

Petroleum-based polymers are part of Barbie’s DNA.

Acrylonitrile-Butadiene-Styrene (ABS) is known for strength and flexibility. This thermoplastic polymer is used in Barbie’s torso to provide impact and heat resistance. EVA (Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate), a copolymer made up of ethylene and vinyl acetate, protects Barbie’s smooth surface.

The Mattel doll also includes Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT), a thermoplastic polymer often used as an electrical insulator. A mineral component facilitates PBT injection molding of her “full figure,” according to the company. Barbie’s hair and many of her designer outfits are made from the world’s first synthetic fiber, nylon, invented in 1935 (see Nylon, a Petroleum Polymer and more articles in Petroleum Products).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); History of Paola, Kansas (1956); Where it all began: The story of the people and places where the oil & gas industry began: West Virginia and southeastern Ohio

(1956); Where it all began: The story of the people and places where the oil & gas industry began: West Virginia and southeastern Ohio (1994); Oil And Gas In Oklahoma: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma

(1994); Oil And Gas In Oklahoma: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma (2013); Kettles and Crackers – A History of Wyoming Oil Refineries

(2013); Kettles and Crackers – A History of Wyoming Oil Refineries (2016); Utah Oil Shale: Science, Technology, and Policy Perspectives

(2016); Utah Oil Shale: Science, Technology, and Policy Perspectives (2016); George P. Mitchell: Fracking, Sustainability, and an Unorthodox Quest to Save the Planet (2019); Sour Lake, Texas: From Mud Baths to Millionaires, 1835-1909

(2016); George P. Mitchell: Fracking, Sustainability, and an Unorthodox Quest to Save the Planet (2019); Sour Lake, Texas: From Mud Baths to Millionaires, 1835-1909 (1995); Rigs-to-reefs: the use of obsolete petroleum structures as artificial reefs

(1995); Rigs-to-reefs: the use of obsolete petroleum structures as artificial reefs (1987); Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century Hardcover

(1987); Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century Hardcover (1996); American Fads

(1996); American Fads (1985). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1985). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 17, 2025 | Petroleum Companies

Oklahoma showman Maj. Gordon W. “Pawnee Bill” Lillie caught oil fever in 1918.

With America joining “the war to end all wars” in Europe and oil demand rising, a popular Oklahoma showman launched his own petroleum exploration and refining company.

Although not as well known as his friend Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody of Wyoming, Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie was “a showman, a teacher, and friend of the Indian,” according to his biographer.

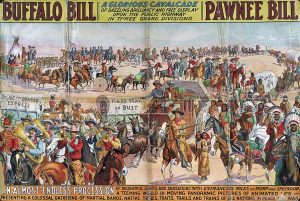

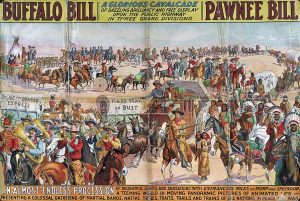

Pawnee Bill and Buffalo Bill combined their shows from 1908 to 1913 as “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East.”

Maj. Lillie was admired for being a “colonizer in Oklahoma and builder of his state,” noted Stillwater journalist Glenn Shirley in his 1958 book Pawnee Bill: A Biography of Major Gordon W. Lillie.

The two entertainers joined their shows in 1908 to form “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East,” promoted as “a glorious cavalcade of dazzling brilliancy,” noted Shirley, adding that the combined shows offered, “an almost endless procession of delightful sight and sensations.”

But times were changing as public taste turned to a new form of entertainment, motion picture shows. By 1913, the two showmen’s partnership was over and their western cavalcade foreclosed. Lillie turned to other ventures — real estate, banking, ranching, and like his former partner Cody, the petroleum industry.

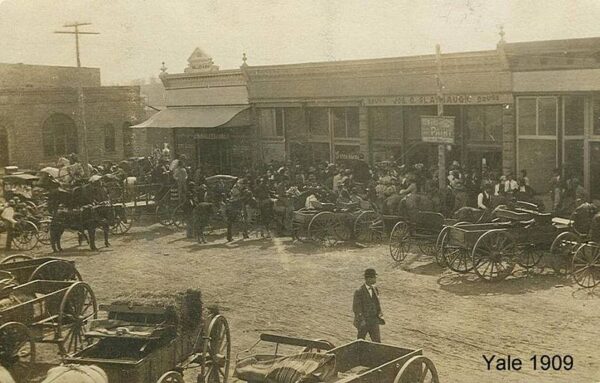

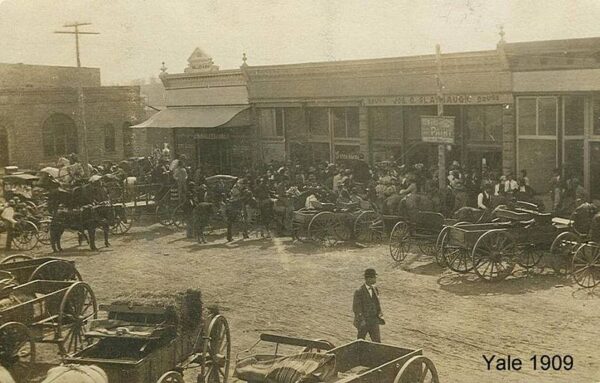

Oklahoma oilfield discoveries near Yale (population of only 685 in 1913) had created a drilling boom that made it home to 20 oil companies and 14 refineries. In 1916, Petrol Refining Company added a 1,000-barrel-a-day-capacity plant in Yale, about 25 miles south of Lillie’s ranch.

The trade magazine Petroleum Age, which had covered the 1917 “Roaring Ranger” oilfield discovery in Texas, reported that for Pawnee Bill, “the lure of the oil game was too strong to overcome.”

Obsolete financial stock certificates with interesting histories like Pawnee Bill Oil Company are valued by collectors.

The Oklahoma showman founded the Pawnee Bill Oil Company on February 25, 1918, and bought Petrol Refining’s new “skimming” refinery in March.

An early type of refining, skimming (or topping) removed light oils, gasoline and kerosene and left a residual oil that could also be sold as a basic fuel. To meet the growing demand for kerosene lamp fuel, early refineries built west of the Mississippi River often used the inefficient but simple process.

Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie (1860-1942).

Lillie’s company became known as Pawnee Bill Oil & Refining and contracted with the Twin State Oil Company for oil from nearby leases in Payne County.

Under headlines like “Pawnee Bill In Oil” and “Hero of Frontier Days Tries the Biggest Game in All the World,” the Petroleum Age proclaimed:

“Pawnee Bill, sole survivor of that heroic band of men who spread the romance of the frontier days over the world…who used to scout on the ragged edge of semi-savage civilization, is doing his bit to supply Uncle Sam and his allies with the stuff that enables armies to save civilization.”

Post WWI Bust

By July 30, 1919, Pawnee Bill Oil (and Refining) Company had leased 25 railroad tank cars, each with a capacity of about 8,300 gallons. But the end of “the war to end all wars” drastically reduced demand for oil and refined petroleum products. Just two years later, Oklahoma refineries were operating at about 50 percent capacity, with 39 plants shut down.

Although Lillie’s refinery was among those closed, he did not give up. In February 1921, he incorporated the Buffalo Refining Company and took over the Yale refinery’s operations. He was president and treasurer of the new company. But by June 1922, the Yale refinery was making daily runs of 700 barrels of oil, about half its skimming capacity.

The Pawnee Bill Oil Company held its annual stockholders meetings in Yale, Oklahoma, an oil boom town about 20 miles from Pawnee Bill’s ranch.

“At the annual stockholders’ meeting held at the offices of the Pawnee Bill Oil Company in Yale, Oklahoma, in April, it was voted to declare an eight percent dividend,” reported the Wichita Daily Eagle. “The officers and directors have been highly complimented for their judicious and able handling, of the affairs of the company through the strenuous times the oil industry has passed through since the Armistice was signed.”

The Kansas newspaper added that although many Independent refineries had been sold at receivers’ sale, “the financial condition of the Pawnee Bill company is in fine shape,”

Buffalo Bill’s Shoshone Oil

What happened next has been hard to determine since financial records of the Pawnee Bill Oil Company are rare. A 1918 stock certificate signed by Lillie, valued by collectors one hundred years later, could be found selling online for about $2,500.

Maj. Gordon William “Pawnee Bill” Lillie’s friend and partner Col. William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody also caught oil fever, forming several Wyoming oil exploration ventures, including the Shoshone Oil Company.

In 1920, yet another legend of the Old West — lawman and gambler Wyatt Earp — began his a search for oil riches on a piece of California scrubland. One century later, his Kern County lease still paid royalties; learn more in Wyatt Earp’s California Oil Wells.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Pawnee Bill: A Biography of Major Gordon W. Lillie (1958). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1958). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Pawnee Bill Oil Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/stocks/pawnee-bill-oil-company. Last Updated: February 19, 2025. Original Published Date: February 24, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | Feb 11, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Public fascination with Mid-Continent “black gold” discoveries briefly switched to natural gas in 1906.

As petroleum exploration wells reached deeper by the early 1900s, highly pressurized natural gas formations in Kansas and the Indian Territory challenged well-control technologies of the day.

Ignited by a lightning bolt in the winter of 1906, a natural gas well at Caney, Kansas, towered 150 feet high and at night could be seen for 35 miles. The conflagration made headlines nationwide, attracting many exploration and production companies to Mid-Continent oilfields even as well control technologies tried to catch up.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jan 16, 2025 | Petroleum Products

When Phillips Petroleum scientists invented a new plastic in the early 1950s, getting it from lab to market proved difficult. Enter Wham-O.

Research scientists in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1951 discovered how to make a durable, high-density polyethylene, and the marketing executives at their oil and natural gas company named it Marlex. But Phillips Petroleum sales reps searched in vain for buyers of the new plastic until the Wham-O toy company found it ideal for making hoops and flying platters.

Prompted by a post World War II boom in demand for plastics, Phillips Petroleum Company invested $50 million to bring its own miracle product — Marlex — to market in 1954. With a high melting point and tensile strength, the synthetic polymer would stand out from the company’s thousands of patents.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jul 20, 2024 | Petroleum Pioneers

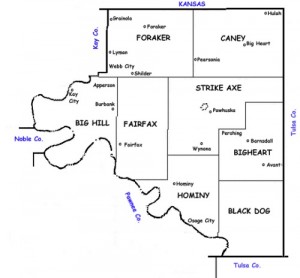

Oil boom 1920s lease auctions earned the Osage millions.

By the 1920s, Oklahoma’s petroleum exploration leases auctioned in the shade of a “Million Dollar Elm” brought prosperity to the Osage Nation. Production from Osage County alone launched the careers of Frank Phillips, J. Paul Getty, Bill Skelly, E.W. Marland, Harry Sinclair — and Clark Gable.

A circa 1920s painting depicts one of the many lease auctions that took place under the “Million Dollar Elm” next to the Osage Nation tribal council house in Pawhuska, Oklahoma.

In the spring of 2003, the Osage nation opened a “Million Dollar Elm” casino a few miles from its council house at Pawhuska, Oklahoma. The name came straight from Osage reservation petroleum history. Multi-million dollar lease auctions took place in the shade of a giant elm next to the council house.

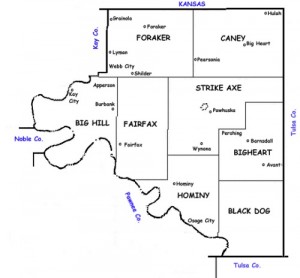

Osage County, at more 2,250 square miles, is the largest county in Oklahoma – larger than Delaware or Rhode Island. On the grounds atop Agency Hill between the county courthouse and the Osage tribal council house, today stands a symbolic elm where auctions regularly took place on hot summer afternoons.

Soon after Oklahoma statehood, more Osage discoveries brought thousands to Bartlesville, Hominy, Fairfax, Grainola and Burbank. All the oilfields produced a high-quality, easily refined oil. First drilled in 1920, the Burbank field and several others soon became one of the richest in Oklahoma.

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth Walters, official auctioneer of the Osage Nation (seen here on June 14, 1921), sold millions of dollars of oil leases in the shade of an elm tree. Photo courtesy Bartlesville Area History Museum.

At its peak, the Burbank oilfield produced more than 70,000 barrels a day from more than 1,800 wells. Phillips Petroleum made a fortune there. Other petroleum companies got their start in Osage oilfields, including Conoco (originally Marland Oil), Skelly Oil, Carter Oil (later incorporated into Standard Oil), and Gypsy Oil Company (later Gulf).

Traces of oil had long been noted in the area, including slicks on creeks and oil seeps. The southern end of the Flint Hills, which ranges down from Kansas, has rocks 298 million years old, according to Jenk Jones Jr. of the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Cottonwood Falls, Kansas.

The Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Company made the first drilling deal with the Osage Tribe, he noted in 1991. The oil company received rights to all drilling in the Osage Nation for 10 years, beginning in 1896. The next year the territory’s first commercial producer was completed, the Nellie Johnstone No. 1 well, in what is now a park in Bartlesville.

All of Osage County was open for bidding after 1916 – just in time for the greatest years of the Osage boom, triggered by demands of World War I and the postwar growth in automobiles.

“To get a sense of how the oil business exploded in the Osage, there were about 6,000 barrels produced in 1900, more than 11 million in 1914. The Osage boom and a vast leap in the number of automobiles coincided remarkably well,” Jones explained in a Tulsa World article.

Colonel Walters on March 2, 1922, sold a million-dollar 160-acre oil lease for the Osage Nation. Walters auctioned another 160-acre Osage lease for $2 million in 1924. Detail of photo in Oil! Titan of the Southwest by Carl Coke Rister, 1949.

During the height of the drilling boom from 1919 to 1928 northwest of Tulsa, more than $202 million was paid to the tribe in oil and natural gas royalties, bonuses, interest and land rentals.

“The Osage fields were an oilman’s dream,” reported Jones. “The oil was a high-grade, with a good conversion to gasoline ratio. It was easily refined, with a very high percentage of kerosene. It was free of sulfur and asphalt.”

According to Corey Bone of the Oklahoma Historical Society, the profitable auctions of Osage mineral rights were based on “headrights” from a 1906 tribal population count.

“Unlike other landholders, the Osage were able to retain collective ownership of subsurface mineral rights, rather than having to accept allotments to individual owners,” Bone explained. “Instead, tribal members received ‘headrights’ that assured them an equal share of mineral rights sales equivalent to income from 658 acres.”

She added that a headright could not be sold, but an individual could sell his or her surface rights. “An average Osage family of a husband, wife, and three children would receive more than $65,000 a year in 1926,” Bone noted.

By 1939, Osage individuals had received more than $100 million in royalties and bonuses.

Million Dollar Auctioneer

Great petroleum wealth for the Osage people brought criminal conspiracies — and the murder of Osage for headrights to their land. The murders eventually led to an FBI investigation, convictions — and changes to the law in 1925.

When the “Reign of Terror” news finally made national headlines, it obscured the the good work of a longtime friend and respected auctioneer of the tribe’s leases. The Osage would erect a statue to their auctioneer, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth Walters, in his hometown of Skedee.

Born in at the end of the Civil War in 1865, his parents had named him after the first Union martyr of the Civil War, Col. Elmer Ellsworth of the 11th New York Volunteers. His friendship helped earn the Osage millions of dollars (learn about Walters, his leases auctions, the dark history of Osage headrights in Million Dollar Auctioneer.

Map of Osage County, Oklahoma, townships courtesy OKGenWeb.

As the auctioneer for the Osage, Walters worked for about $10 a day, beginning in 1912. Later, surrounded by bidding oil company owners E.W. Marland, William Skelly and the Phillips brothers, he regularly set new lease sales records.

Walters would become greatly admired among the Osage of Pawhuska. “He knew the oilmen intimately and was an expert at getting them to raise bids,” Jones explained. “So subtle were their signals that L.E. Phillips reportedly ‘bid’ $100,000 for a lease by brushing a fly away from his nose.”

The elm’s name was not given by tribal leaders – but by reporters and magazine writers who were dramatizing the events when founders of the world’s greatest oil companies came in person to bid. It truly earned its name when 18 tracts brought bonuses of $1 million on a single day, November 11, 1912.

Auctions by Walters would earn about $157 million for the Osage tribe by 1928, two years after the Osage Nation dedicated a statue to their auctioneer, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth Walters, in his hometown of Skedee. The statue depicts the auctioneer shaking hands with his friend Osage Chief Bacon Rind.

Osage Oil Boom

A large cast of national characters are linked to petroleum exploration and production on the Osage Nation. Future president Herbert Hoover, an orphan, spent summer months in Pawhuska after his uncle Major Lahan J. Miles was appointed agent to the Osages in 1878.

Visitors to Barnsdall, Oklahoma, can view a registered petroleum landmark in the middle of Main Street that is considered to be the only such oil well in the world. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Southeast of Pawhuska, the town Pershing was an oil boom town named for Gen. John J. Pershing, leader of U.S. forces in Europe during World War I.

Tom Mix, future silent film star, was a town marshal in Dewey just east of the Osage County border. The Wild West show of the 101 Ranch in Kay County west of the Osage gave him the boost that sent him to Hollywood.

Clark Gable worked as a roustabout in the Osage oilfields, especially around Barnsdall and Pershing, before heading to California for stardom (see Boom Town Burkburnett).

Memories of what took place beneath the Osage Nation elm did not fade after the original tree died in the 1980s. The latest elm, dedicated during a September 15, 2006, ceremony, grows new roots into the historic site. Visitors gamble at six Osage Nation “Million Dollar Elm” casinos.

In 2011, Oklahoma City-based Chaparral Energy reportedly began working on methods to increase production from Osage oilfields that could bring $11 billion to Osage County and provide the Osage Nation with $1.2 billion in royalty payments over the next 30 years.

Editor’s Note: Special thanks to Jenk Jones Jr. and his March 1, 2003, “Osage County History” docent orientation presentation, Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Cottonwood Falls, Kansas.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Underground Reservation: Osage Oil (1985); Oil in Oklahoma

(1985); Oil in Oklahoma (1976); Killers of the Flower Moon (2018). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1976); Killers of the Flower Moon (2018). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Million Dollar Elm,” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/million-dollar-elm. Last Updated: April 20, 2025. Original Published Date: March 24, 2014.

(1956); Where it all began: The story of the people and places where the oil & gas industry began: West Virginia and southeastern Ohio

(1994); Oil And Gas In Oklahoma: Petroleum Geology In Oklahoma

(2013); Kettles and Crackers – A History of Wyoming Oil Refineries

(2016); Utah Oil Shale: Science, Technology, and Policy Perspectives

(2016); George P. Mitchell: Fracking, Sustainability, and an Unorthodox Quest to Save the Planet (2019); Sour Lake, Texas: From Mud Baths to Millionaires, 1835-1909

(1995); Rigs-to-reefs: the use of obsolete petroleum structures as artificial reefs

(1987); Plastic: The Making of a Synthetic Century Hardcover

(1996); American Fads

(1985). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.