by Bruce Wells | May 27, 2025 | Petroleum Products

How oilfield paraffin created Vaseline and Maybelline cosmetics.

Few associate 1860s oil wells with women’s eyes, but they are fashionably related. From paraffin to Vaseline, this is the story of how the goop that accumulated around the sucker rods of America’s earliest oil wells made its way to eyelashes.

In 1865, a 22-year-old Robert Chesebrough left the prolific oilfields of Pithole and Titusville, Pennsylvania, to return to his Brooklyn, New York, laboratory. He carried samples of a waxy substance that clogged wellheads. He already had dabbled in the “coal oil” business with experiments on refinery processes.

Robert Chesebrough will find a way to purify the waxy paraffin-like substance that clogged oil wells in early Pennsylvania petroleum fields. Photo courtesy Unilever Corp.

Chesebrough’s laboratory expertise included distilling cannel coal into kerosene (coal oil), a lamp fuel in high demand among consumers. He also knew of the process for refining crude oil into a better kerosene.

Thus, when Edwin L. Drake completed the first U.S. oil well in August 1859, Chesebrough was among those who rushed to Pennsylvania oilfields to make his fortune.

“Now commenced a scene of excitement beyond description,” reported Scientific American. “The Drake well was immediately thronged with visitors arriving from the surrounding country, and within two or three weeks thousands began to pour in from the neighboring States.”

Chesebrough was convinced he too could get rich from the “black gold” of Pennsylvania’s oilfields.

Oilfield Sucker Rod Wax

Amid the Venango County exploration and production chaos, the young chemist noted a waxy buildup often confounded drilling. This paraffin-like substance clogged the wellhead and drew curses from riggers who had to stop drilling to scrape it away.

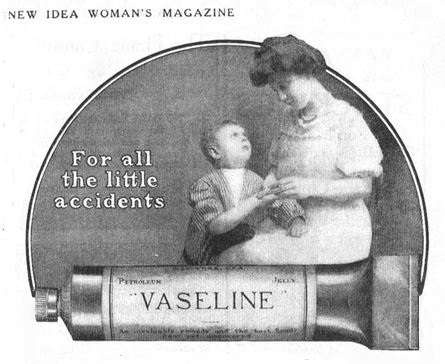

Robert Chesebrough consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day and lived to be 96. This early bottle is from the collection of the Drake Well Museum in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

The only virtue of this goopy oilfield “sucker rod wax” was as an immediately available first aid for the abrasions, burns, and other wounds routinely afflicting the crews.

Paraffin to Vaseline

Chesebrough abandoned his notion of drilling a gusher and returned to New York, where he worked in his laboratory to purify the troublesome sucker-rod wax, which he dubbed “petroleum jelly,” one of America’s earliest petroleum products.

By August 1865, Chesebrough had filed the first of several patents “for purifying petroleum or coal oils by filtration.”

The chemist experimented with the analgesic effects of his extract by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying the purified petroleum jelly. He also gave it to Brooklyn construction workers to treat their minor scratches and abrasions.

After refining oilfield wax, Chesebrough experimented by inflicting minor cuts and burns on himself, then applying his petroleum balm.

On June 4, 1872, Chesebrough patented a new product – “Vaseline.” His paraffin to Vaseline patent extolled the balm’s virtues as a leather treatment, lubricator, pomade, and balm for chapped hands. Chesebrough soon had a dozen wagons distributing the product around New York.

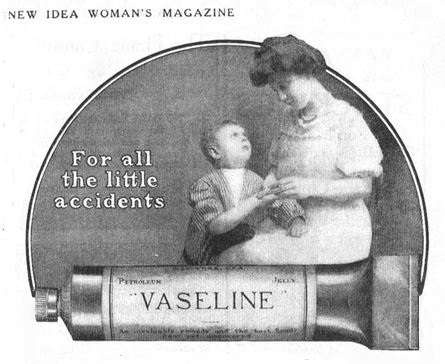

Customers used the “wonder jelly” creatively: treating cuts and bruises, removing stains from furniture, polishing wood surfaces, restoring leather, and preventing rust. Within 10 years, Americans were buying it at the rate of a jar a minute

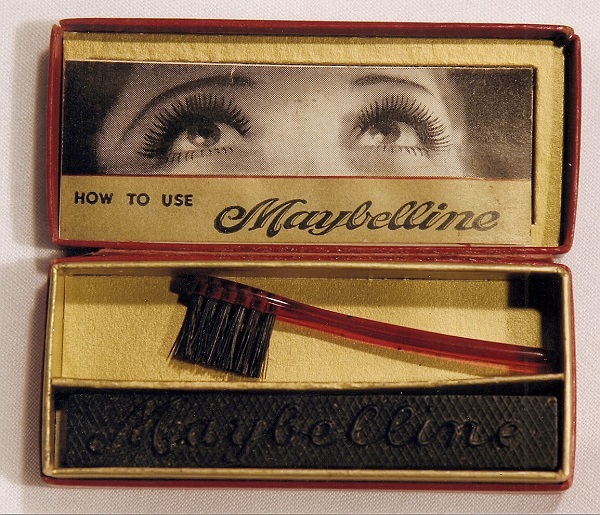

Women had once used toothpicks to mix lamp black with Vaseline. By 1917, Tom Williams was selling premixed “Lash-Brow-Ine” by mail order. Photo courtesy Sharrie Williams.

An 1886 issue of Manufacture and Builder even reported, “French bakers are making large use of vaseline in cake and other pastry. Its advantage over lard or butter lies in the fact that, however stale the pastry may be, it will not become rancid.”

Flavor notwithstanding, Chesebrough himself consumed a spoonful of Vaseline each day. He lived to be 96 years old. It was not long before thrifty young ladies found another use for Vaseline.

Mabel’s Eyelashes

As early as 1834, the popular book Toilette of Health, Beauty, and Fashion suggested alternatives to the practice of darkening eyelashes with elderberry juice or a mixture of frankincense, resin, and mastic.

“By holding a saucer over the flame of a lamp or candle, enough ‘lamp black’ can be collected for applying to the lashes with a camel-hair brush,” the book advised.

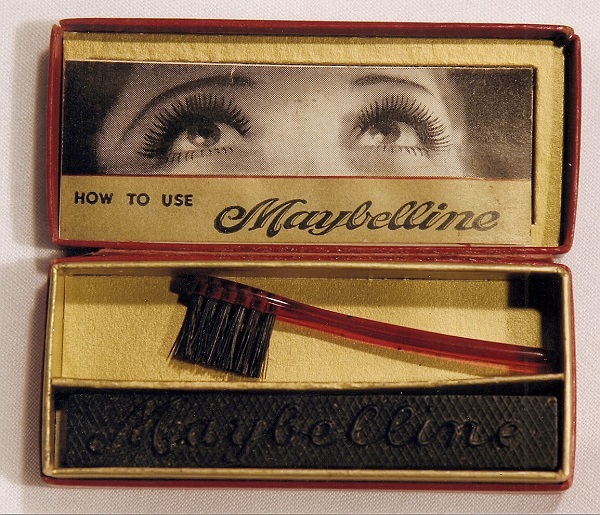

Chesebrough’s female customers found that mixing lamp black with Vaseline using a toothpick made an impromptu mascara. Some sources claim that Miss Mabel Williams in 1913 employed just such a concoction preparing for a date. Williams was dating Chet Hewes.

Women were using Vaseline to make mascara by 1915. Cosmetic industry giant Maybelline traces its roots to the petroleum product. “What a Difference Maybelline Does Make” magazine ad from 1937.

Perhaps using coal dust or some other readily available darkening agent, she applied the mixture to her eyelashes for a date. Her brother, Thomas Lyle Williams, was intrigued by her method and decided to add Vaseline in the mixture, noted a Maybelline company historian.

Lash-Brow-Ine

A more reliable version of the story — told by Williams’ grandniece Sharrie Williams — has Mabel demonstrating “a secret of the harem” for her brother.

“In 1915, when a kitchen stove fire singed his sister Mabel’s lashes and brows, Tom Lyle Williams watched in fascination as she performed what she called ‘a secret of the harem’ mixing petroleum jelly with coal dust and ash from a burnt cork and applying it to her lashes and brows,” Sharrie Williams explained in her 2007 book, The Maybelline Story and the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It.

“Mabel’s simple beauty trick ignited Tom’s imagination and he started what would become a billion-dollar business,” concluded Williams.

Silent screen stars like Theda Bara, right, helped glamorize Maybelline mascara. By the 1930s, the paraffin to Vaseline to mascara concoction was available at five-and-dime stores for 10 cents a cake.

Inspired by his sister’s example, he began selling the mixture by catalog, calling it “Lash-Brow-Ine” (an apparent concession to the mascara’s Vaseline content). Women loved it.

When it became clear that Lash-Brow-Ine had potential, Williams, doing business in Chicago as Maybell Laboratories, on April 24, 1917, trademarked the name as a “preparation for stimulating the growth of eyebrows and eyelashes.”

Mail-Order Mascara

With sales exceeding $100,000 by 1920, Williams decided to rename the mascara Maybelline in honor of his sister, who worked with him in the Chicago office. Maybell Laboratories was renamed Maybelline in 1923 and concentrated on eye makeup. Mabel married Chet Hewes in 1926.

An unlikely petroleum product for women’s eyes.

Whatever its petroleum product beginnings, Hollywood helped expand the Williams family cosmetics empire. The 1920s silent screen had brought new definitions to glamour. Theda Bara – an anagram for “Arab Death” – and Pola Negri, each with daring eye makeup, smoldered in packed theaters across the country.

Maybelline trumpeted its mail-order mascara in movie and confession magazines as well as Sunday newspaper supplements. Sales continued to climb. By the 1930s, Maybelline mascara was available at the local five-and-dime store for 10 cents a cake.

Both Vaseline, now part of Unilever, and Maybelline, later a subsidiary of L’Oréal, have continued as highly successful products, distantly removed from northwestern Pennsylvania’s “Wonder Jelly” introduced in 1870.

Special thanks to Linda Hughes, granddaughter of Mabel and Chet Hewes, who reviewed the American Oil & Gas Historical Society’s paraffin to Vaseline to Mascara article. She asked AOGHS to note that Mabel was very dedicated to her brother’s work –- and helped run the Maybelline company in Chicago.

Crayola Crayons

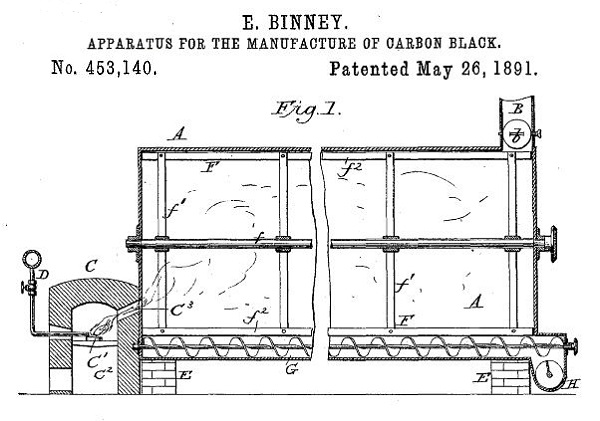

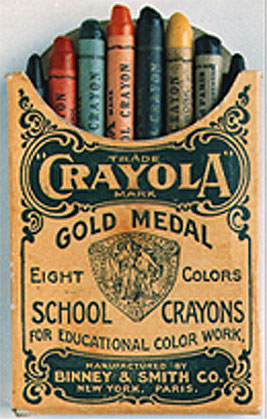

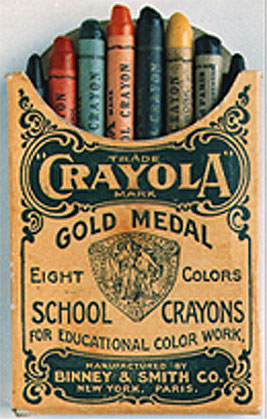

Paraffin from early U.S. oilfields also proved key to the phenomenal success of business partners Edwin Binney and C. Harold Smith, who in 1891 patented an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.”

Soon, the Pennsylvania inventors mixed carbon black with oilfield paraffin to introduce a paper-wrapped black crayon marker able to “stay on all” and named “Staonal,” still sold today. The company also manufactured a popular “dustless chalk” for schoolrooms and a red, iron oxide barn paint.

By 1903, the Binney & Smith Company added color to paraffin for a new product, “Crayola” crayons. Learn more about their petroleum products in Carbon Black & Oilfield Crayons. Oilfield paraffin also found its way into novelty candies like “wax lips.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Maybelline Story: And the Spirited Family Dynasty Behind It (2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/vaseline-maybelline-history. Last Updated: June 1, 2025. Original Published Date: March 1, 2005.

by Bruce Wells | May 21, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

Marketing icon “Dino” and friends introduced children to wonders of the Mesozoic era courtesy of Sinclair Oil.

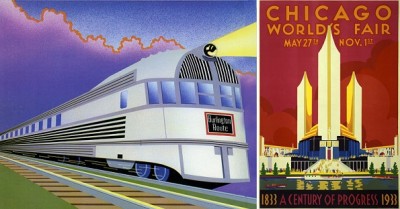

Harry Ford Sinclair established his petroleum company in 1916, making it one of the oldest continuous names in the U.S. energy industry. Appearing among other Sinclair Oil Company dinosaurs during the 1933-1934 World’s Fair in Chicago, “Dino” became a marketing icon whose popularity with children remains today. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | May 21, 2025 | Petroleum Transportation

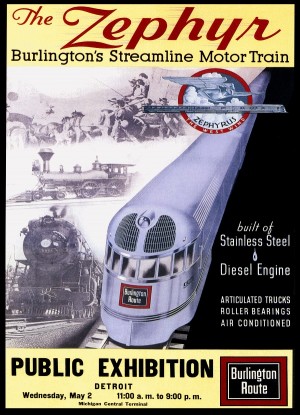

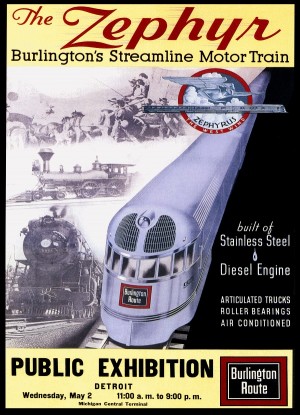

Powered by a diesel-electric engine in 1934, a streamliner cut steam locomotion travel time by half.

“Once I built a railroad, I made it run, made it race against time. Once I built a railroad; now it’s done. Brother, can you spare a dime?” — Bing Crosby, 1932.

By the early 1930s, America’s passenger railroad business was in deep trouble. In addition to the Great Depression, the once-dominant transportation industry faced growing competition from automobiles. New refineries produced vast amounts of gasoline, thanks to giant oilfield discoveries like Spindletop Hill in Texas.

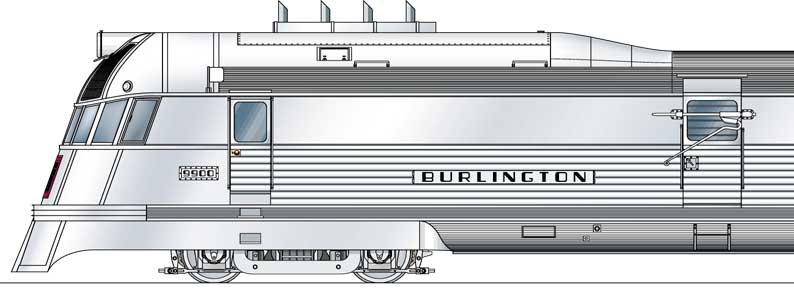

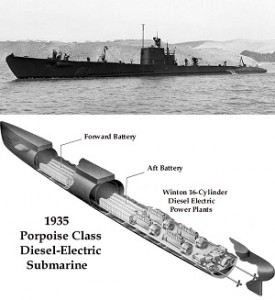

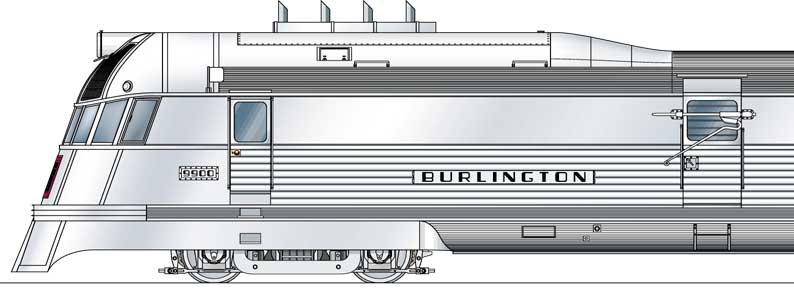

Diesel-electric engines pioneered by General Motors and Winton Engine Company saved America’s railroad passenger industry with a four-fold power-to-weight gain. Photo courtesy Model Railroader magazine, January 1999.

Despite the hard economic times, gasoline fueled more than 30 million cars, trucks, and buses on U.S. roads (many without asphalt paving).

Locomotive Power

Primitive diesel engines of the day remained heavy and slow, but a powerful railroad diesel-electric engine was in the future. It had been 60 years since coal-burning steam locomotives and the transcontinental railroad had linked America’s east and west coasts on May 10, 1869.

Used since about 1925, diesel engines were heavy — producing only a single horsepower from 80 pounds of engine weight.

Meanwhile, railroad steam engine technology had advanced since the “golden spike” of 1869 in Promontory Point, Utah. But locomotives still “belched steam, smoke, and cinders,” noted one railroad historian, adding, “Passengers often felt like they had been on a tour of a coal mine.”

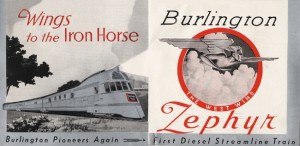

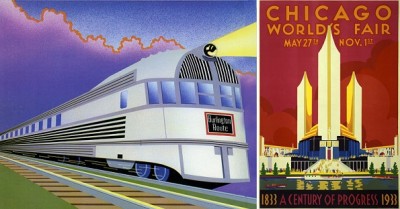

The two streamliner trains that changed America’s railroad industry in the late 1930s: Union Pacific M-10000 (left) and Burlington Zephyr. The Zephyr has been preserved as an exhibit at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry. Photo courtesy Union Pacific Museum.

While most U.S. locomotives were still steam-powered, General Electric in 1913 designed and built the first commercially successful gasoline-powered engine locomotive. Two General Motors 175-horsepower V-8s powered two 600-volt, direct current generators. They propelled the 57-ton locomotive to a top speed of 51 miles per hour.

The locomotive Dan Patch, considered by many to be the first successful internal combustion engine locomotive in the United States.

The Electric Line of Minnesota Company purchased the new gasoline-powered electric hybrid for $34,500. Marketing executives picked the name Dan Patch. a world-champion harness horse at the time. By 1930, powerful diesel engines with electric generators transformed train travel with streamliners.

Distillate Engines

In rail yards, low-geared diesels had been used from about 1925, mainly as engines for “switcher” locomotives used for maneuvering, but they were slow, according to historian Richard Cleghorn Overton. Powerful distillate-burning engines proved heavy and difficult to maintain.

The powerful diesel-electric Zephyr arrived in 1934; its technology was a result of the Navy’s search for an improved submarine engine.

Overton, author of Burlington Route: A History of the Burlington Lines, noted the burning fuels ranged from a low-grade gasoline to painter’s naphtha and diesel.

The distillate railroad engines emitted an oily smoke and often produced only a single horsepower from 80 pounds of engine weight. The common four-stroke engines fouled easily and required multiple spark plugs per cylinder.

Help for America’s failing passenger railroads would come from U.S. Navy diesel-electric engine technology, wrapped in a stainless steel Art Deco locomotive.

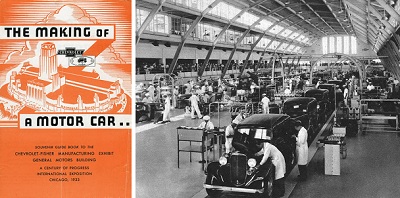

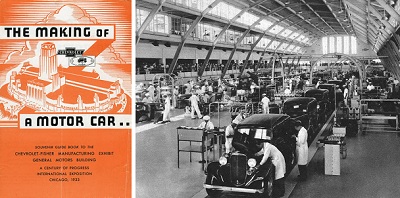

New diesel-electric engines generated power for the “Making of a Motor Car” exhibit at the 1933 Century of Progress fair in Chicago. The assembly line fascinated visitors who watched from overhead galleries.

“Wings to the Iron Horse…Burlington pioneers again — the first diesel streamline train,” proclaimed passenger rail advertisements in the 1930s. The long-awaited technology for railroad diesel-electric engines had arrived.

Diesel-Electric Hybrid

With the Nazi threat and war on the horizon, the U.S. Navy needed a lighter-weight, more powerful diesel engine for its submarines. The Navy also recognized it had been too slow in converting its surface vessels from coal to fuel oil (see Petroleum and Sea Power). General Motors joined the nationwide competition to develop a new diesel engine for the Navy.

Seeking engineering and production expertise, in 1930 GM acquired the Winton Engine Company of Cleveland, Ohio. Winton, established in 1896 as Winton Bicycle Company, was an early automobile manufacturer. Winton Engine Company evolved into a developer of engines for marine applications, power companies, pipeline operators — and railroads.

America’s first diesel-electric train, the Burlington Zephyr, was a transportation milestone.

With GM’s financial backing, Winton engineers designed a radical new two-stroke diesel that delivered one horsepower per 20 pounds of engine weight. It provided a four-fold power to weight gain.

The Model 201A prototype — a 503-cubic-inch, 600 horsepower, 8-cylinder diesel-electric engine — used no spark plugs, relying instead on newly patented high-pressure fuel injectors and a 16:1 compression ratio for ignition.

Powered by an eight-cylinder Winton 201A diesel engine, the revolutionary streamliner traveled the 1,015 miles from Denver to Chicago in just over 13 hours — a passenger train record.

At Chicago’s Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1933, GM evaluated two railroad diesel-electric engines, using them to generate power for its “Making of a Motor Car” exhibit. The working demonstration of a Chevrolet assembly line fascinated thousands of visitors who watched from overhead galleries.

The Burlington Line

One visitor happened to be Ralph Budd, president of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (known as the Burlington Line). Budd recognized the locomotive potential of these extraordinary new diesel-electric power plants. He saw them as a perfect match for the lightweight “shot-welded” stainless steel rail cars pioneered by the Edward G. Budd (no relation) Manufacturing Company in Philadelphia.

During its “dawn to dusk” record-breaking run, the Zephyr burned only $16.72 worth of diesel fuel.

Edward Budd pioneered supplying all-steel bodies to the automobile industry in 1912. His success in steel stamping technology made the production of them cheaper and faster. By 1925, his system was used to produce half of all U.S. auto bodies.

However, the Depression put the Budd Manufacturing Company almost $2,000,000 in the red — prompting its fortuitous diversification into the railroad car market to generate revenue. When approached by Burlington President Ralph Budd in 1933, this Budd was ready.

Chicago World’s Fair visitors line up to admire the stainless steel beauty of the Burlington Zephyr, which will soon be featured in a Hollywood movie. Eight major U.S. railroads soon convert to efficient diesel-electric locomotives. Photo from a Burlington Route Railroad 1934 postcard.

Within a year, the two technologies were successfully merged with the creation of the Winton 201A-powered Burlington Zephyr, America’s first diesel-electric train. It would change railroad transportation history.

Submarine Engines

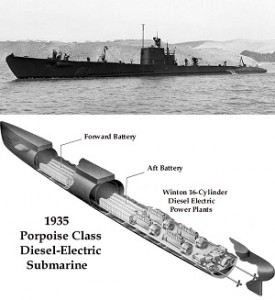

General Motors in 1932 won the Navy’s competition for a lightweight and powerful diesel-electric. The Navy decided a 16-cylinder Winton would power a new class of submarines.

Winton diesel-electric engines powered a new generation of U.S. submarines. The first of its class, Porpoise (SS-172), joined the fleet in 1935 and served throughout World War II.

In 1935, the USS Porpoise became the first to join the fleet, and it served throughout World War II. All of the silent-service’s diesel-electrics power plants descended from the Burlington Zephyr. They would remain part of the fleet until replaced by nuclear propulsion.

The Speedy Zephyr

When the Zephyr rolled into Chicago’s Century of Progress exhibition on May 26, 1934, it ended a nonstop 13-hour, 4-minute, and 58-second “dawn to dusk” promotional run from Denver. Powered by a single eight-cylinder Winton 201A diesel, the streamliner cut average steam locomotive time by half.

The Zephyr had traveled 1,015 miles at an average speed of 76.61 miles per hour, It often sped along the route in excess of 112 mph — amazing lines of trackside spectators. Crowds of Zephyr-watchers could be found from Colorado to Illinois.

During its record-breaking run, the Zephyr burned just $16.72 worth of diesel fuel (about four cents per gallon). The same distance in a coal steamer would have cost $255. Construction innovations included the specialized shot-welding that joined sheets of stainless steel.

Further, the lightweight steel resisted corrosion so it didn’t have to be painted.

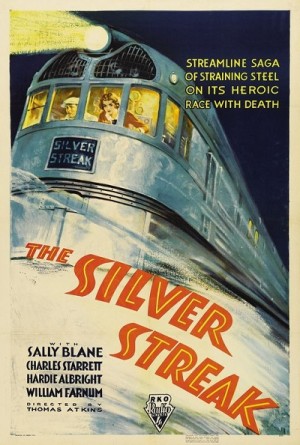

Considered a 1934 “B” movie — intended for the bottom half of double features — ”The Silver Streak” would remain a favorite of many railroad history fans.

Americans fell in love with the Zephyr. Four months after its high-speed appearance at Chicago’s Century of Progress, the streamliner made its 1934 Hollywood film debut, starring as “The Silver Streak” for an RKO picture.

Burlington loaned its Zephyr for the movie’s filming. Repainted, the company logo on the front became the Silver Streak. “The streamlined train, platinum blonde descendant of the rugged old Iron Horse, has been glorified by Hollywood in the modern melodrama,” proclaimed the New York Times.

Surprisingly, the black-and-white “B” movie came and went without drawing many theatergoers. But it has since won its place in movie history as a rail-fan favorite, according to a 2001 article in the Zephyr Online. “It did have a lot of action, and the location shots of the Zephyr are an interesting record of this pioneer.”

The RKO film should not be confused with 20th Century Fox’s 1976 comedy “Silver Streak” filmed in Canada using Canadian Pacific Railway equipment from the Canadian, a transcontinental passenger train.

End of Steam

Meanwhile, by the end of 1934, eight major U.S. railroads had ordered diesel-electric locomotives. The engine technology’s cost advantages in manpower, maintenance, and support were quickly apparent.

Despite the greater initial cost of diesel-electric, a century of steam locomotive dominance soon came to an end. By the mid-1950s, steam locomotives were no longer being manufactured in the United States.

A Zephyr competitor, the Union Pacific M-10000 built by the Pullman Car & Manufacturing Company, also showcased railroad diesel-electric engine technology at the Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago.

In fact, the aluminum M-10000 streamliner was revealed six weeks earlier than the Zephyr. Recognized as America’s first streamliner, the M-10000 was cut up for scrap in 1942. The Zephyr (later renamed the Pioneer Zephyr) ended up on display at the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Burlington Route: A History of the Burlington Lines (1965); Burlington’s Zephyrs, Great Passenger Trains (2004); The Great Railroad Revolution: The History of Trains in America

(2004); The Great Railroad Revolution: The History of Trains in America (2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2013). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Adding Wings to the Iron Horse.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/transportation/adding-wings-to-the-iron-horse. Last Updated: May 21, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | May 20, 2025 | Petroleum Products

Crayola — a 1903 petroleum product name combining the French words craie, chalk, and oléagineux, containing oil.

Many petroleum products hide in plain sight. For Pennsylvania’s Benny & Smith Company, common oilfield paraffin changed the company’s future by coloring children’s imaginations. Before inventing Crayola crayons, the partners patented a “dustless chalk,” a red oxide paint, and Staonal — “stay-on-all” — the blackest of black markers.

Three decades after America’s first oil well at Titusville, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons began with an 1881 refining patent by Edwin Binney to make carbon black, an intensely black pigment. Binney and partner C. Harold Smith had launched their company in Easton to sell inks, black polishes, and chalk for schoolroom blackboards.

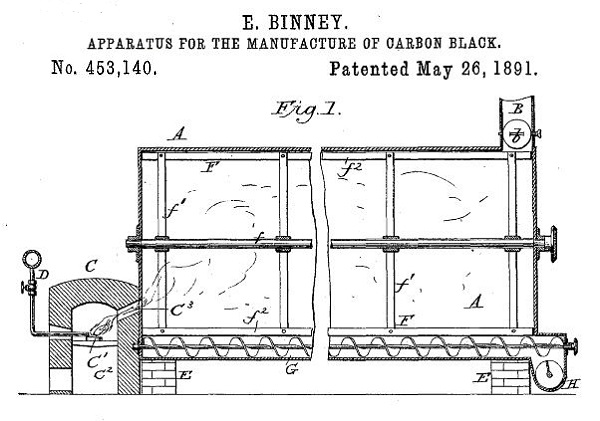

Binney & Smith Company received an 1891 patent for an “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black,” which produced a fine, soot-like black pigment — far better than any other in use.

Pennsylvania’s booming oilfields would prove key to success, beginning with using natural gas in a patented “Apparatus for the Manufacture of Carbon Black.” Binney & Smith Company later would add oilfield paraffin — the bane of oil producers since it clogged wells — and mix in colors to create a petroleum product named Crayola.

Manufacturing Carbon Black

On May 28, 1891, Binney received a patent for the company’s method to efficiently produce a fine, soot-like substance more intensely black than any other pigment in use at the time.

“The objects of my invention are to manufacture lamp-black from oil in an improved and economical manner, whereby waste of the product and unnecessary expenditure of labor are avoided,” Binney noted in his patent application.

His patent (No. 453,140) proclaimed a process to “manufacture carbon-black from gas in such a manner as to obtain improved quality of black which shall have the soft flaky texture of lamp-black made in ordinary ways.”

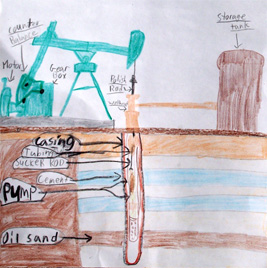

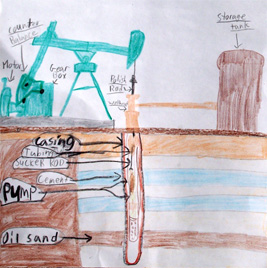

A fifth-grader’s skillful use of crayons illustrates oil production. Image courtesy Pioneer Oil Museum of New York, Bolivar.

The young U.S. petroleum industry, rapidly expanding its refineries to fuel kerosene for lamps, supplied Binney & Smith with oil and natural gas feedstock for the company’s carbon black. Revolving metal drums cooled the heat and smoke directed from the burning gas.

“Stay on All”

The company’s refining process produced a fine, soot-like substance of incredible blackness — a better pigment than any other. Binney & Smith’s carbon black received an award at the 1900 Paris Exposition, a world’s fair of the century’s achievements.

Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania inventors mixed their carbon black product with oilfield paraffin and other waxes to introduce a paper-wrapped black crayon marker for crates and barrels. The company promoted the marker as being able to “stay on all” and accordingly named “Staonal.”

Resulting from an 1891 carbon black patent, Binney & Smith added oilfield paraffin to produce a black marker. Staonal is still sold.

Staonal became a highly successful company product, but the concentrated carbon black content precluded its use by children. The company earlier had found great success manufacturing “dustless chalk” for schoolrooms and red iron oxide for a red paint for barns.

Classroom Chalk

Although they longed for color, students in Alice Stead Binney’s classroom had to settle for dustless chalk. In fact, An-Du-Septic dustless chalk proved so popular among turn-of-the-century teachers that it won a Gold Medal at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Teachers like Alice loved the tidy new product, but their choices were limited. Pencils of the day were primitive, with square “leads” made from a variety of clays, slates, and graphite. Color writing implements were the toxic and expensive imports of artists, best kept away from schoolchildren.

Experiments in 1902 produced An-Du-Septic, a white dustless chalk soon popular with teachers. Photo courtesy Benny and Smith Company.

Alice’s husband Edwin, and his cousin, C. Harold Smith, created An-Du-Septic chalk as a consequence of expanding their pigment business into the sideline production of slate pencils for schools.

In Easton, the Binney & Smith Company, formerly the Peekskill Chemical Works, made its reputation by producing a red iron oxide for paint and carbon black for paints, inks, and iron stoves. Binney & Smith also produced shoe polishes. School teachers and their students would bring change.

Slate pencils and the very successful An-Du-Septic dustless chalk put Binney & Smith salesmen into America’s classrooms. The company’s sales force listened to teachers and learned there would be a ready market for inexpensive, non-toxic, brightly colored crayons.

“Crayola” from Oilfield Paraffin

In 1903, Binney & Smith launched a colorful product that would forever change childhoods. Alice Binney provided the name by combining the French word for chalk, craie, with the Old French word oléagineux — meaning something that contains oil.

The manufacturing process began with mixing small batches of carefully measured and hand-mixed pigments, paraffin, talc and other waxes. Employees individually rolled paper labels and pasted them onto each crayon by hand.

Identically packed into small boxes, thousands easily could be shipped in wooden crates. Sixteen Crayola crayons sold for 10 cents; eight for 5 cents: red, yellow, orange, green, blue, violet, black, and brown. Crayola became an instant hit.

Binney and Smith produced the first box of eight Crayola crayons in 1903 — red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, brown, and black.

The company’s proprietary formulas have remained a closely guarded secret as demand for its crayons has grown worldwide. Production capacity reportedly is more than four million crayons every day, thanks to oilfield paraffin from distant petroleum refineries delivered to Crayola’s Easton factory in railroad tank cars.

In January 2007, Binney & Smith became Crayola LLC in recognition of the company’s number one brand. The company is now known as Crayola. Crayola has grown to become a $500 million a year business — a successful union of the petroleum industry to the colorful world of children’s imaginations.

“This organizational and name change showcases the company’s Crayola brand, sold by Binney & Smith since 1903,” explained the company, which also opened a museum in Easton. Crayola is sold in more than 80 countries, “and represents innovation, fun, kids and quality.”

As paraffin continued to find its way into products (see The Crude History of Mabel’s Eyelashes), manufacturers in 1912 for the first time added Binney & Smith’s carbon black to tires. Until the addition of carbon black to improve durability, auto tires were white.

Carbon Black Hits the Road

In 1839, bankrupt Philadelphia hardware merchant and erstwhile inventor Charles Goodyear accidentally dropped rubber and sulfur on a hot stovetop. The rubber charred like leather yet remained elastic, a discovery that led to “vulcanization.”

During the new process, natural rubber could be transformed into an industrial product with innumerable uses. Goodyear’s famous lawyer, Daniel Webster, praised his client’s invention. “It introduces quite a new material into the manufacture of the arts, that material being nothing less than elastic metal,” Webster proclaimed.

Automobile tires were the ideal application for this new product. Between 1895 and 1905, more than 77,000 new automobiles were registered in the United States (See Cantankerous Combustion — First U.S. Auto Show).

The tires of this 1904 Oldsmobile Model N Touring Runabout were not chosen for their color. Until B.F. Goodrich introduced “carbon black” into the vulcanizing process in 1910, auto tires were white.

Natural rubber pigments and zinc oxide used in the manufacturing process gave tires their while color. At the time, most cities had a downtown maximum speed limit of 10 mph.

In 1910, the B.F. Goodrich Company found that adding carbon black to the vulcanizing process dramatically improved strength and durability. The material came from controlled combustion of both oil and natural gas. Its use in tires created an immense market — initially consuming one pound of carbon black for every two pounds of rubber.

Correspondingly, as America’s automobile industry grew, so did demand for tires and carbon black. By 1931, Texas annually produced more than 200 million pounds of carbon black from just 31 plants — about 75 percent of America’s total production.

Today, most of America’s carbon black is still produced in Texas and Louisiana. Demand remains closely associated with auto tires. Cabot Corporation — founded in Pennsylvania in 1882 — is the largest U.S. producer of the intensely black petroleum product. By 2024, the company operated 43 manufacturing facilities in more than 20 countries.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Crayola Creators: Edward Binney and C. Harold Smith, Toy Trailblazers (2016); Carbon Black, Its Manufacture, Properties, and Uses (2018); The B.F. Goodrich Story Of Creative Enterprise 1870-1952

(2016); Carbon Black, Its Manufacture, Properties, and Uses (2018); The B.F. Goodrich Story Of Creative Enterprise 1870-1952 (2010). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2010). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “’Carbon Black & Oilfield Crayons.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/oilfield-paraffin. Last Updated: May 22, 2025. Original Published Date: September 1, 2007.

by Bruce Wells | May 19, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

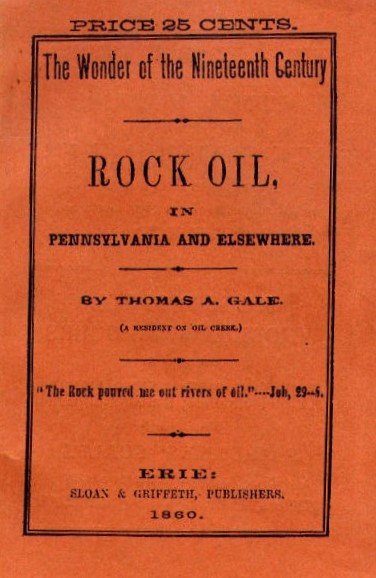

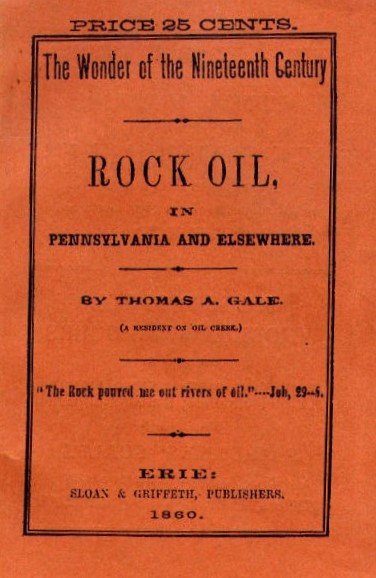

Less than 10 months after Edwin L. Drake and his driller William “Uncle Billy” Smith completed the first commercial U.S. oil well on August 27, 1859, along Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, Thomas A. Gale wrote a detailed study about rock oil — and helped launch the petroleum age.

Published in 1860, The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere described a radical fuel source for the popular lamp fuel kerosene, which had been made from coal for more than a decade.

“Those who have not seen it burn may rest assured its light is no moonshine; but something nearer the clear, strong, brilliant light of day,” Gale declared in his 25-cent pamphlet printed in Erie by Sloan & Griffith Company.

Thomas Gale’s 80-page pamphlet in 1860 marked the beginning of the petroleum age, illuminated with kerosene lamps.

“In other words, rock oil emits a dainty light; the brightest and yet the cheapest in the world; a light fit for Kings and Royalists, and not unsuitable for Republicans and Democrats,” Gale added.

Oil in Rocks

Gale’s descriptions of the value of petroleum helped launch investments in new exploration companies, especially as he noted the commercial qualities of Pennsylvania oil for refining into kerosene, the distilled “coal oil” invented in 1848 by Canadian chemist Abraham Gesner.

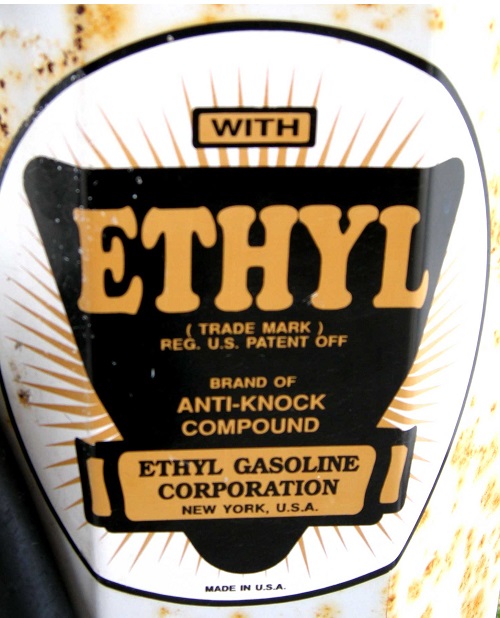

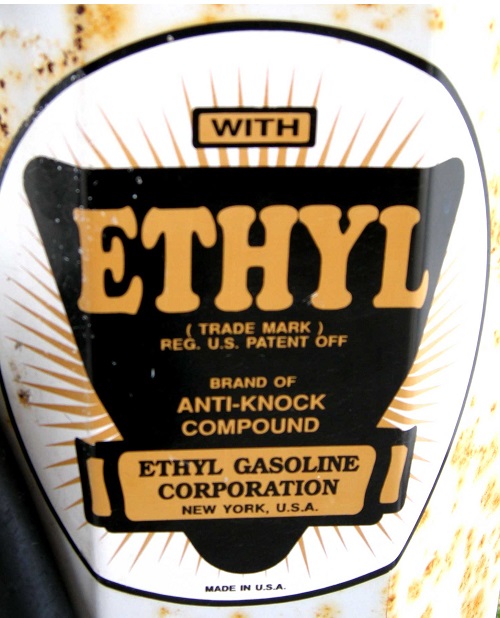

Historians regard the 80-page publication as the first book about America’s petroleum industry. The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere was almost forgotten until 1952, when the Ethyl Corporation of New York republished the work. Only three original copies were known to exist.

“Not by the widest stretch of the imagination could Thomas Gale have realized, when he put down his pen on June 1, 1860, that he had written a book destined to become one of the rarest of all oil books,” proclaimed the Ethyl historian when the company republished Gale’s book.

Ethyl Corporation noted the scarcity of copies of the book had prevented “all but a few historians” from giving the book the attention it deserved.

“Gale wrote his book to satisfy a public desire for more information about petroleum. Newspapers had carried belated accounts of Drake’s discovery well, and the mad scramble for oil that followed, but actually the world knew little about petroleum.”

“The Rock poured…”

The book’s 11 chapters explain practical aspects of the new petroleum industry. Chapters one and two, “What is Rock Oil?” and “Where is the Rock Oil found?” were followed by “Geological Structure of the Oil Region.”

Chapters four through six explained the early technologies (and costs) for pumping the oil, while the next two chapters examine “Uses of Rock Oil.” The final three chapters offered “Sketches of several oil wells,” “History of the Rock Oil Enterprise,” and “Present condition and prospects of Rock Oil interests in different localities.”

Chapter three in The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere features the “geological structure of the oil region,” today part of Oil Creek State Park in northwestern Pennsylvania.

Originally published by Sloan & Griffith of Erie, Pennsylvania, the 1860 cover noted the author as “a resident of Oil Creek” and included a biblical quote, “The Rock poured me out rivers of oil,” from Job, 29:6.

In addition to mysteriously burning gasses and “tar pits,” explorers for millennia have referenced signs of coal, bitumen, and substances very much like petroleum — a word derived from the Latin roots of petra, meaning “rock” and oleum meaning “oil.”

But did Thomas Gayle’s 1860 work produce the first book about oil as Ethyl Corporation historians believed when the company reprinted it in 1952? In fact, there have been many references to natural oil seeps recorded millennia ago (including in the Bible), according to a geologist who has researched the earliest sightings of petroleum.

Illuminating Petroleum

Several years before the 1859 oil discovery in Pennsylvania, businessman George Bissell hired a prominent Yale chemist to study the potential of oil and its products to convince potential investors (see George Bissell’s Oil Seeps).

“Gentlemen, it appears to me that there is much ground for encouragement in the belief that your company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive processes, they may manufacture very valuable products,” reported Benjamin Silliman Jr. in 1855.

Silliman’s groundbreaking “Report on the Rock Oil, or Petroleum, from Venango Co., Pennsylvania, with Special Reference to its Use for Illumination and Other Purposes,” convinced the petroleum industry’s earliest investors to drill at Titusville. Cable-tool technology developed for brine wells would drill the well.

According to historian Paul H. Giddens in the 1939 classic, The Birth of the Oil Industry, Silliman’s 1855 report, “proved to be a turning-point in the establishment of the petroleum business, for it dispelled many doubts about its value.”

The Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company would evolve into the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut, which became America’s first oil company after Drake completed the first U.S. commercial well drilled seeking oil in 1859.

Rock Oil Products

In addition to providing oil for refining into kerosene lamps (and someday rockets), oilfield discoveries led to many products. Early petroleum products included axle greases, an oilfield paraffin balm, and in Easton, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons.

Further, oil offered an improved asphalt prior to the first U.S. auto show in November 1900 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

Ethyl Corporation was established in 1923 by General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey,

Responding to consumer demand for better automobile gasoline, General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey established the Ethyl Corporation in 1923. The company initially downplayed the danger of tetraethyl lead. Leaded gas would be banned for use in cars in the 1970s

Importantly, high-octane leaded aviation fuel proved vital for victory in World War II — and the additive still fuels many piston-engine aircraft and racecars.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere (1952); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1939); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Oil Book of 1860.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/first-oil-book-of-1860. Last Updated: May 17, 2025. Original Published Date: May 31, 2020.

(2010); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.