by Bruce Wells | Oct 25, 2025 | Petroleum Art

The first pitcher ever inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, Walter “The Big Train” Johnson, worked in California oilfields as a teenager; his famed career began with a company town baseball team. Players sometimes made it to the Big Leagues — and the Baseball Hall of Fame.

As baseball became America’s favorite pastime in the early 20th century, booming oil towns fielded winning teams with names that reflected their communities’ enthusiasm and often their livelihood.

In Texas, the booming petroleum town of Corsicana fielded the Oil Citys — and made baseball history in 1902 with a 51 to 3 drubbing of the Texarkana Casketmakers. Oil Citys catcher Jay Justin Clarke hit eight home runs in eight at bats during the game, still an unbroken baseball record.

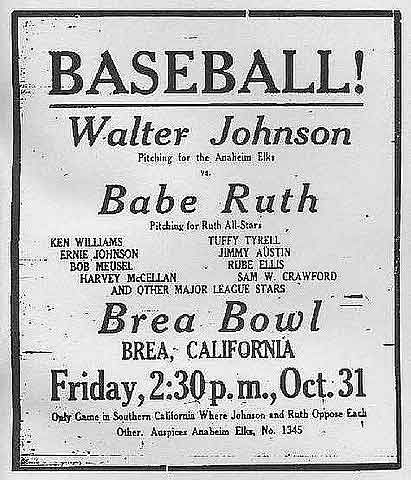

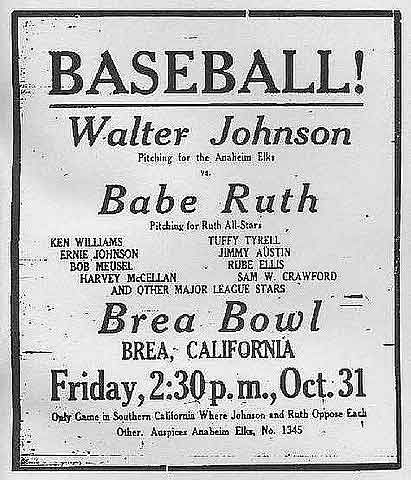

Former pitcher for the Olinda Oil Wells — Walter “The Big Train” Johnson — joined “Babe” Ruth in a 1924 exhibition game. Johnson was among the first players inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1922, the Wichita Falls minor league team lost its opportunity for a 25th consecutive victory when the league determined the team had “doctored the baseball.” The Wichita Falls ballpark caught fire in June during a game and burned to the ground. It was a memorable season.

The Double-A team Tulsa Drillers began in 1977 when the Lafayette Drillers moved to Tulsa.

In Oklahoma oilfields, the Okmulgee Drillers for the first time in baseball history had two players who combined to hit 100 home runs in a single season of 160 games. First baseman Wilbur “Country” Davis and center fielder Cecil “Stormy” Davis accomplished their home run record in 1924, although their team faded away by 1927.

With a growing population thanks to giant oilfield discoveries at nearby Red Fork (1901) and Glenn Pool (1905), the Tulsa Oilers dominated the Western League for a decade, winning the pennant in 1920, 1922, and 1927-1929. The name has continued in the hockey league’s Tulsa Oilers.

In 1977, the Double-A affiliate team for Major League Baseball, the Tulsa Drillers, arrived in the city from Lafayette, Louisiana.

First Night Game

For baseball’s first official night game on April 28, 1930, a company town baseball team — the Producers of Independence, Kansas — lost to the Muskogee Chiefs 13 to 3. The game was played under portable lights supplied by the Negro National League’s Kansas City Monarchs.

The Olinda No. 1 well of 1898 created an oil boom town. Hundreds of wells once pumped oil around the Olinda Oil Museum and Trail near Brea, California.

The Independence Producers were one of the 96 teams in the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, later known as Minor League Baseball.

Iola Gasbags and Borger Gassers

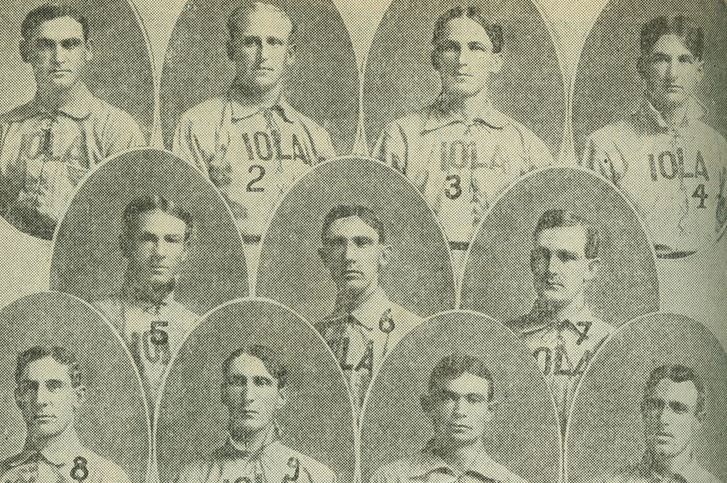

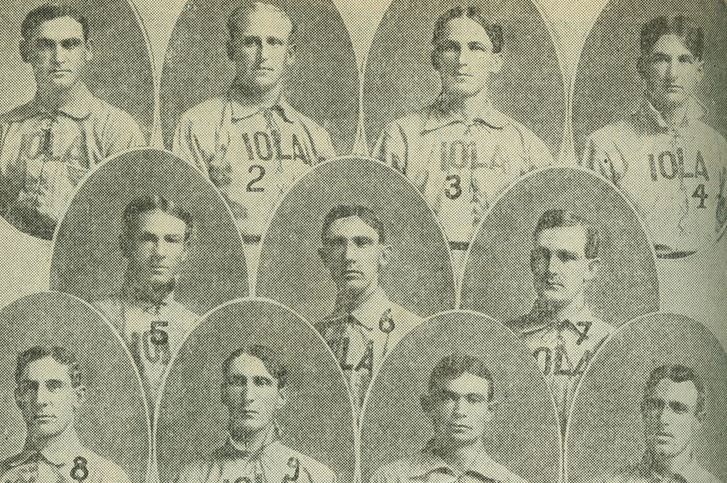

Thanks to mid-continent oil and natural gas discoveries, in just nine years beginning in 1895, Iola, Kansas, grew into a city of more than 11,000. Gas wells lighted the way. The Iola Gasbags reportedly adopted their team name not for the resource, but after becoming known as braggers in the Missouri State League.

“They traveled to these other cities, and they’d be bragging that they were the champions, so people started giving them the nickname Gasbags,” reported baseball historian Tim Hagerty in a 2012 National Public Radio interview.

A natural gas boom in Kansas led to a baseball team being named the Iola Gasbags, pictured here in 1904. Photo courtesy National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

In 1903, the players renamed themselves the Iola Gaslighters — but had a change of heart and reverted to the original name the following season.

“They said, ‘You know what? Yeah, we are, We’re the Gasbags.'” added Hagerty, author of Root for the Home Team: Minor League Baseball’s Most Off-the-Wall Names and the Stories Behind Them. “I think the state of Kansas may take the prize for the most terrific names — the Wichita Wingnuts, the Wichita Izzies, the Hutchinson Salt Packers…and the Iola Gasbags.”

In the Texas Panhandle, the petroleum-related town baseball team Borger Gassers disappeared after the 1955 season, despite Gordon Nell hitting a record-setting 49 homers in 1947. Team owners blamed television and air-conditioning for reducing minor league baseball attendance and profitability.

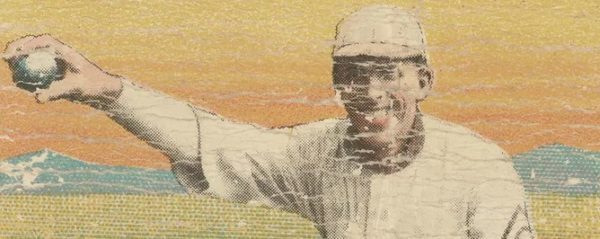

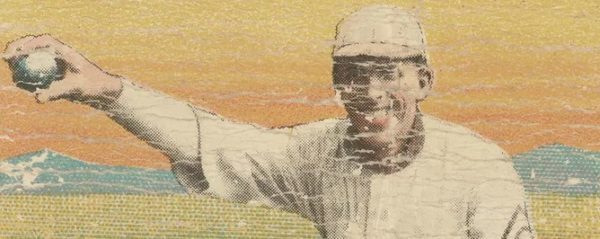

Detail from 1909 baseball card featuring Pacific Coast League pitcher Jimmy Wiggs. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

In Beaumont, Texas, site of the great Spindletop oil discovery of 1901, minor league baseball lasted for decades under several names. The first team, the Beaumont Oil Gushers of the South Texas League, was fielded in 1903. By the 1904 season the team was known as the Millionaires and then the Oilers before becoming the Beaumont Exporters in 1920.

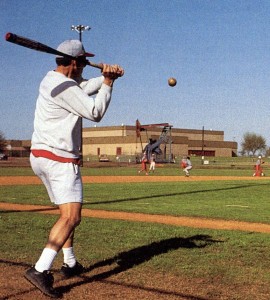

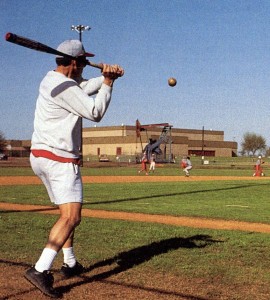

East of Dallas, in Van, Texas, fielding practice at the oil town’s high school includes a pumping reminder of the prolific oilfield discovered in 1929. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Although many thought the name should be changed to the Refiners, reflecting the city’s industry, for the 1950 season the team was briefly known as the Roughnecks (a former company town baseball team name still popular).

Beaumont’s last AA Texas League team was the Golden Gators, which folded in 1986. Another team in the Texas League, the company town baseball team Shreveport Gassers, on May 8, 1918, played 20 innings against the Fort Worth Panthers before the game was finally declared a tie at one to one.

Pitching for the Olinda Oil Wells

Perhaps baseball’s greatest product from the oilfield was a young man who was a roustabout in the small oil town of Olinda, California. Walter Johnson (1887-1946) would earn national renown as the greatest pitcher of his time. His fastball was legendary.

In 1894, the Union Oil Company of Santa Paula purchased 1,200 acres in northern Orange County for oil development. Four years later the first oil well, Olinda No. 1, came in and created the oil boom town. Soon, the Olinda baseball players began making a name for themselves among the semi-pro teams of the Los Angeles area.

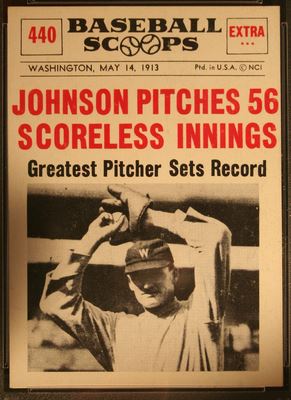

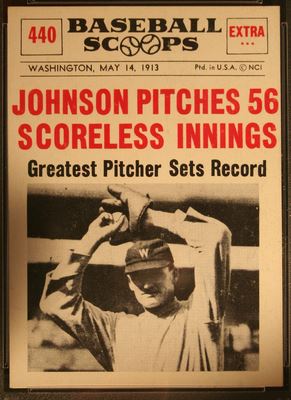

A 1961 baseball card notes headline of the former California oilfield roustabout’s amazing 1913 pitching record, which lasted until Don Drysdale pitched 58 scoreless innings in 1968.

By 1903, the Orange County team was sharing newly built Athletic Park in Anaheim, “two hours south of Olinda by horse and buggy,” noted one historian. Youngster Walter Johnson rooted for the local team, the Oil Wells.

Johnson, originally from Humboldt, Kansas, moved to the thriving oil town east of Brea with his family when he was 14. He attended Fullerton Union High School and played baseball there while working in the nearby oilfields. His high school pitching began making headlines, including a 15-inning game against rival Santa Ana High School in 1905 where he struck out 27.

Today, tourists visit the Olinda Oil Museum and Trail. This historic Orange County site includes Olinda Oil Well No. 1 of 1898, the oil company field office and a jack-line pump building.

By 17, Johnson was playing for his oil town baseball team, the Olinda Oil Wells, as its ace pitcher. He shared in each game’s income of $25, according to Henry Thomas in Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train.

“Not a bad split for nine players considering that a roustabout in the oilfields started at $1.50 a day,” Thomas noted in his book. Johnson finished with a winning season and soon moved on to the minor leagues.

Johnson’s major league career began in 1907 in Washington, D.C., where he played his entire 21-year baseball career for the Washington Senators. The former oil patch roustabout in 2022 remained major league baseball’s all-time career leader in shutouts with 110, second in wins (417) and fourth in complete games (531).

In 1936, “The Big Train” Johnson was inducted into baseball’s newly created Hall of Fame with four others: Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, and Christy Mathewson. In 1924, Johnson returned to his California oil-patch roots. On October 31, he and his former baseball teammates played an exhibition game in Brea against Babe Ruth and the Ruth All-Stars.

The Brea Museum & Historical Society today includes exhibits, rare photographs, and research facilities. There’s also an ongoing project recreating Brea in miniature.

Texon Oilers of the Permian Basin

On May 28, 1923, a loud roar was heard when the Santa Rita No. 1 well erupted in West Texas. People as far away as Fort Worth traveled to see the well.

Near Big Lake, Texas, on arid land leased from the University of Texas, Texon Oil and Land Company made the discovery (the school would earn millions of dollars in royalties). The giant oilfield, about 4.5 square miles, revealed the extent of oil reserves in West Texas. Exploration spread in the Permian Basin, still one of the largest U.S. oil-producing regions.

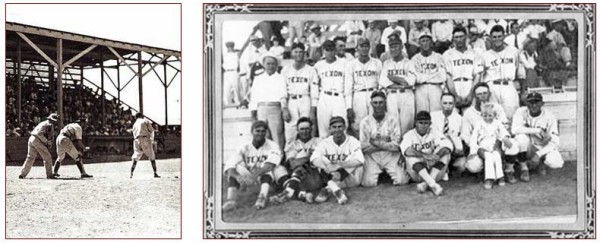

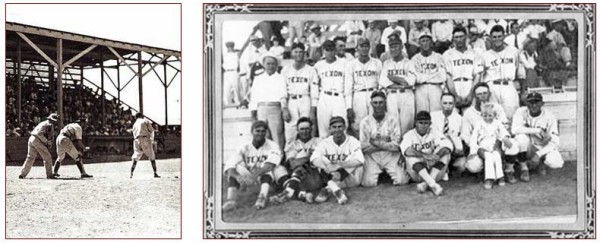

The first oil company town in the Permian Basin, Texon, was founded in 1924 by Big Lake Oil Co. The Texon Oilers won championships in 1933, 1934, 1935, and 1939. Texon today is a tourist attraction as a ghost town.

Early Permian Basin discoveries created many boom towns, including Midland, which some would soon refer to as “Little Dallas.”

By 1924, Michael L. Benedum, a successful independent oilman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and other successful independent producers — wildcatters — formed the Big Lake Oil Company. The new company established Texon, the first oil company town in the Permian Basin. Texon residents fielded a company town baseball team.

Today a ghost town, Texon was considered a model oil community. It had a school, church, hospital, theater, golf course, swimming pool – and a semi-pro company baseball team.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, the Texon Oilers baseball team was the centerpiece of the employee recreation plan of Levi Smith, vice president and general manager of the Big Lake Oil Company. Smith organized the club after he founded the Reagan County town west of Big Lake.

The Permian Basin oilfield was featured in a 2002 movie featuring a high school teacher and baseball coach. Image from Walt Disney Pictures poster.

By the summer of 1925 a baseball field was ready for use. In 1926 a 500-seat grandstand completed the facility. “In 1929 the Big Lake Oil Company began a tradition of hosting a Labor Day barbecue for employees and friends, highlighted by a baseball game,” noted historian Jane Spraggins Wilson.

“Management consistently attempted to schedule well-known clubs, such as the Fort Worth Cats and the Halliburton Oilers of Oklahoma,” added Wilson, who explained that during the Great Depression, “before good highways, television, and other diversions, the team was a source of community cohesiveness, entertainment, and pride.”

After World War II, with its famous oilfield diminishing and the town losing population, aging Oilers left the game for good, Wilson reports. By the mid-1950s the Texon Oilers company town baseball team was but a memory.

Hollywood visits Oilfields

The 2002 movie “The Rookie” — filmed almost entirely in the Permian Basin of West Texas — featured a Reagan County High School teacher. Based on the “true life” of baseball pitcher Jimmy Morris, it tells the story of baseball coach, Morris (played by Dennis Quaid), who despite being in his mid-30s, briefly makes it to the major leagues.

The movie, promoted with the phrase “It’s never too late to believe in your dreams,” begins with a flashback scene near Big Lake, the Santa Rita No. 1 drilling site.

At the beginning of the 2002 movie “The Rookie,” Catholic nuns christened the Santa Rita No. 1 cable-tool rig. In reality, one of the well’s owners climbed the derrick and threw rose petals given to him by Catholic women investors.

As the well is being drilled, Catholic nuns are shown carrying a basket of rose petals to christen it for the patron saint of the impossible – Santa Rita. “Much is made of the almost mythic importance of oil in Big Lake, with talk of the Santa Rita oil well,” explained ESPN in The Rookie in Reel Life.

Learn more about the Permian Basin by visiting the Petroleum Museum in Midland.

Company Town Baseball: Oilmen of Whiting, Indiana

In 1889, the Standard Oil Company began construction on its massive, 235-acre refinery in Whiting, Indiana. Today owned by BP, the Whiting refinery is the largest in the United States.

Whiting has been home to the Northwest Indiana Oilmen since 2012.

In 2012, Whiting fielded a baseball team. On June 3, the Northwest Indiana Oilmen crushed the Southland Vikings 14-3 at Oil City Stadium in Standard Diamonds Park for the first win in franchise history. The Oilmen team became one of eight in the Midwest Collegiate League, a pre-minor baseball league.

Standard Oil’s giant refinery in Whiting, Indiana, processed “sour crude” in the early 1900s. Now owned by BP, it is the largest U.S. refinery. The city of Whiting incorporated in 1903.

“The name Oil City Stadium celebrates Whiting’s history as a refinery town tucked away in the Northwest corner of Indiana for over 120 years,” noted team owner Don Popravak about the oil company town baseball. “The BP Refinery, located just beyond the outfield fence, is a constant reminder of the blue-collar attitude Whiting was built on,” he added.

CITGO and Oil History

With the arrival of baseball’s opening day in 2024, David Krell published a book about the Boston Red Sox and the role of the former Cities Service Company — CITGO — red triangle sign at Fenway Park. While researching The Fenway Effect: A Cultural History of the Boston Red Sox, Krell discovered the extensive history behind the company and its sign at Fenway, the team’s home ballpark since 1912.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Textile League Baseball: South Carolina’s Mill Teams, 1880-1955 (2004); The Fenway Effect: A Cultural History of the Boston Red Sox (2024). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2004); The Fenway Effect: A Cultural History of the Boston Red Sox (2024). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oilfields of Dreams – Gassers, Oilers, and Drillers Baseball.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/oil-town-baseball. Last Updated: October 21, 2025. Original Published Date: September 1, 2007.

by Bruce Wells | Oct 25, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

As she researched her family’s distant connection to the U.S. oil patch, Marianne Jans of the Netherlands contacted the American Oil & Gas Historical Society in 2023. She has since continued to hope visitors to the AOGHS Petroleum History Research Forum might add to her limited information about her great-great uncle who worked in Texas oilfields, apparently as a drilling contractor from the 1920s until the early 1930s.

Ralph “Dutch” Weges

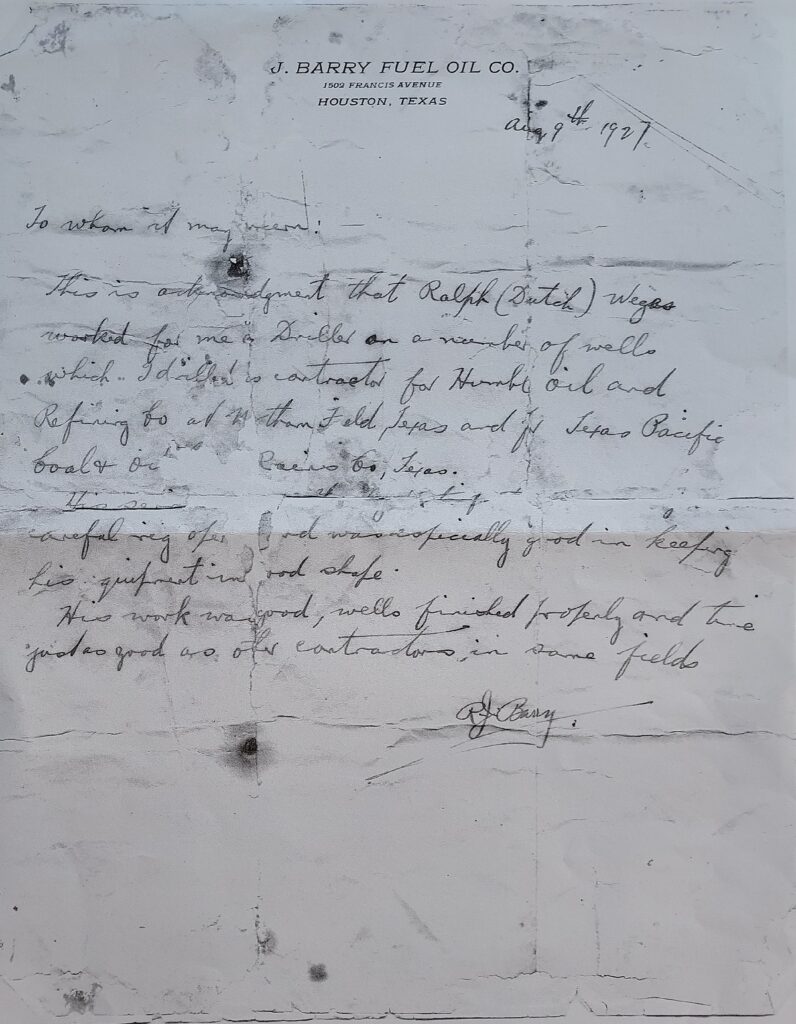

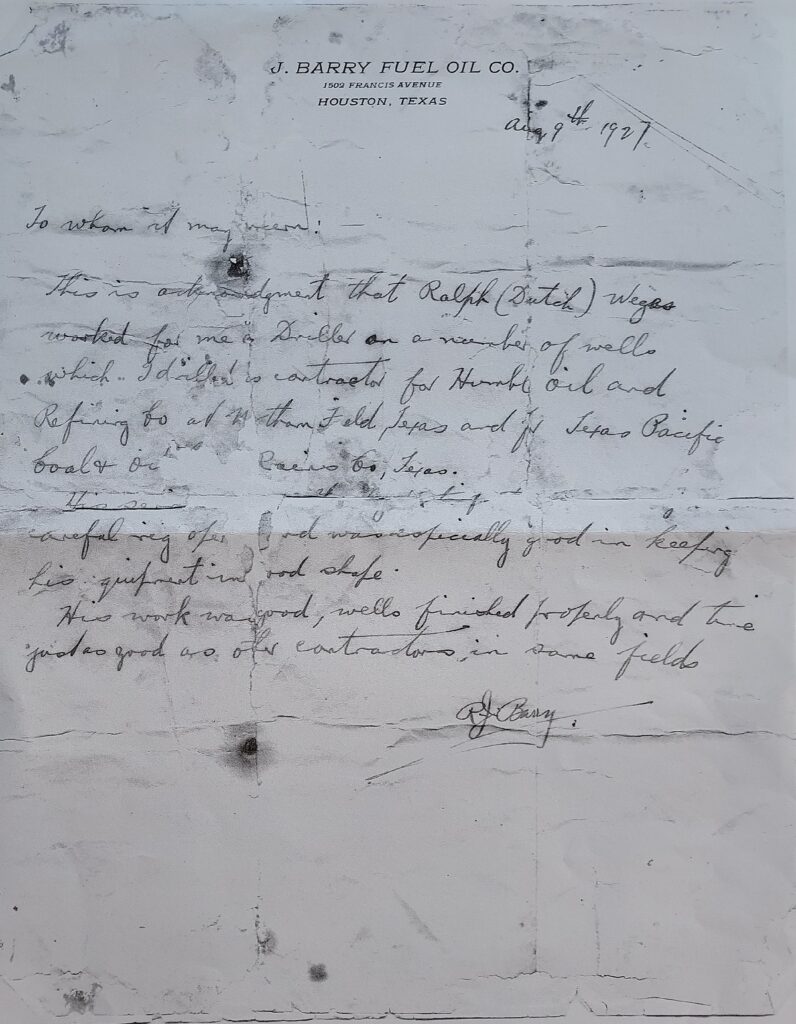

Although details are scarce, Jans seeks news about her great-great uncle Ralph “Dutch” Weges — who in 1962 reportedly returned to the Netherlands by ship. His petroleum-related career included serving on merchant vessels. Regarding his work in Texas, she has a 1927 letter of recommendation with some clues.

Marianne Jans’ scan of the August 1927 Barry Fuel Oil Company’s letter of recommendation for her great-great uncle, Ralph Weges.

“In papers he left behind, he also had a recommendation from his employer in 1927,” according to Jans. “J. Barry Fuel Oil Co. is not in your list of historic companies, so I am sending this document.” she added.

Transcription of the great-great uncle’s letter, dated August 9, 1927:

J. Barry Fuel Oil Co.

1501 Francis Avenue

Houston, Texas

Aug 9th 1927

To whom it may concern:

This is acknowledgement that Ralph (Dutch) Weges

worked for me [&] Drilled on a number of wells

which I drilled as contractor for Humble Oil and

Refining [unreadable] Northern Field, Texas and [for] Texas Pacific

Coal & Oil [unreadable] Co, Texas.

His [unreadable] careful rig [unreadable] and was specifically good in keeping

his equipment in good shape.

His work was good, wells finished properly and time

just as good as other contractors in same fields.

RJ Barry

J. Barry Fuel Oil

Not finding more information about the J. Barry Fuel Oil Company, Jans learned more about the two well-documented companies J. Barry worked with as a drilling contractor.

Humble Oil and Refining Company (now ExxonMobil) was founded in 1917. The company, which would discover many oilfields, in 1933 signed an historic lease with the King Ranch. The other company referenced in the letter was the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company.

SS La Campine

In addition, Ralph Weges had other connections with the U.S. petroleum industry, according to Jan’s research. Her great-great uncle traveled overseas aboard the SS La Campine in September 1916.

Launched in 1889, La Campine was an early transatlantic oil tanker owned by the American Petroleum Company of Rotterdam and later by an Esso subsidiary in Belgium (it was sunk by a German submarine during World War I).

“What surprised me, was that Ralph Weges was anyway on board two ships that transported cargo for Esso, now Exxon Mobile,” Jans noted. “So he already worked for a petroleum/oil company on these ships. First as a 2nd cook and later petty officer. Two other vessels, the Anacortes and the SS Vigo, I must research further.”

As her investigation into family history continues from the Netherlands, Marianne Jans seeks information about her great-great uncle’s overseas career, the J. Barry Fuel Oil Company, and his role in Texas oilfields,

Please post reply in comments section below or email bawells@aoghs.org.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Driller from Netherlands.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/driller-from-netherlands. Last Updated: October 20, 2025. Original Published Date: October 24, 2023.