by Bruce Wells | Feb 18, 2026 | Petroleum in War

Shelling of the Ellwood field at Santa Barbara created mass hysteria — and the “Battle of Los Angeles.”

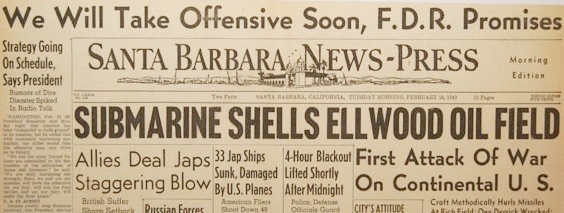

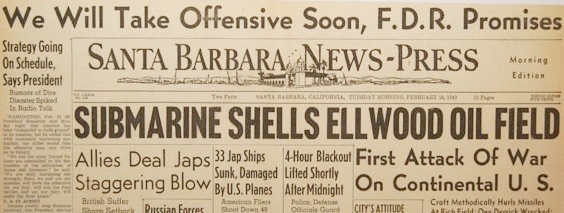

Soon after America entered World War II, an Imperial Japanese Navy submarine attacked a refinery and oilfield near Los Angeles, the first attack of the war on the continental United States. The submarine’s deck gun fired about two dozen rounds, causing little damage — but it resulted in the largest mass sighting of UFOs in American history.

The February 23, 1942, Imperial Japanese Navy submarine’s shelling of a Los Angeles refinery caused little damage but created invasion (and UFO) hysteria. Photo courtesy Goleta Valley Historical Society.

At sunset on February 23, 1942, Imperial Japanese Navy Commander Kozo Nishino and his I-17 submarine lurked 1,000 yards off the California coast. It had been less than three months since the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Los Angeles residents were tense. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Feb 17, 2026 | Petroleum Technology

Public fascination with Mid-Continent “black gold” discoveries briefly switched to natural gas in 1906.

As petroleum exploration wells reached deeper by the early 1900s, highly pressurized natural gas formations in Kansas and the Indian Territory challenged well-control technologies of the day.

Ignited by a lightning bolt in the winter of 1906, a natural gas well at Caney, Kansas, towered 150 feet high and at night could be seen for 35 miles. The conflagration made headlines nationwide, attracting many exploration and production companies to Mid-Continent oilfields even as well control technologies tried to catch up.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Feb 11, 2026 | Petroleum Pioneers

Reports of a “mineral tar” from the 1840s helped H.L. Hunt discover an oilfield a century later.

Swallowing “tar pills” supposedly had been curing ills since the mid-1800s, but Alabama’s petroleum industry officially began in 1944 with a Choctaw County well drilled by a Texas wildcatter. On February 17, independent producer Haroldson Lafayette “H.L.” Hunt completed his Jackson No. 1 well after discovering Alabama’s first oilfield. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Feb 11, 2026 | Petroleum Art

Artist Bob “Daddy-O” Wade used petroleum pipelines to create a Texas landmark.

More than 2.5 million miles of oil and natural gas pipelines crisscross the United States. In 1993, an offbeat Texas sculptor repurposed about 70 feet to create a work of art.

Many Texas travelers at some point have witnessed the monumental sculptures of Bob “Daddy-O” Wade, known for “keeping it weird” since he made the scene in Austin in 1961. Decades of giant artworks by “Daddy-O” have reflected his unusual Texas sense of scale. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Feb 10, 2026 | Petroleum Technology

From eccentric wheels to the counterbalanced “nodding donkey,” inventing ways to produce oil.

In a remote northwestern Pennsylvania valley on August 27, 1859, Edwin L. Drake completed America’s first commercial oil well — launching the U.S. petroleum industry. Drake borrowed a common kitchen hand pump to retrieve the important new resource from a depth of 69.5 feet.

Seeking oil for the Seneca Oil Company for refining into a popular lamp fuel, kerosene, Drake’s shallow well created a new exploration and production industry; it wasn’t long before necessity and ingenuity combined to find something more efficient for producing oil from a well.

(more…)