by Bruce Wells | Sep 29, 2023 | Petroleum Pioneers

Giant Mid-Continent oilfield revealed in 1915 by emerging science of petroleum geology.

Community leaders in El Dorado, Kansas, were desperate for their town to live up to its name, especially after big natural gas discoveries at nearby Augusta and at Paola, south of Kansas City. It would be oil, not natural gas, that would do just that when a 1915 well revealed a giant oilfield east of Wichita. In 1918, the El Dorado field would produce almost 29 million barrels of oil.

One-hundred years after the historic discovery, the Butler County Times-Gazette told the prolific oilfield’s “black gold” story.

“In 1915, about 3,000 people called the rural agricultural community of El Dorado home,” the newspaper reported. “They had no idea events toward the end of that year would begin something that would forever change not just El Dorado, but the state and an entire industry.”

Petroleum Geologists

The science of petroleum geology played a key role in discovering the El Dorado oilfield — and many other Mid-Continent fields that followed. Drilled by Wichita Natural Gas, a subsidiary of Cities Service Company, beginning in late September 1915, the October 5 exploratory well revealed a 34-square-mile oilfield.

A marker erected in 1940 at the Stapleton No. 1 well commemorates the October 5, 1915, discovery of the El Dorado, Kansas, oilfield. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Stapleton No. 1 well produced 95 barrels a day from 600 feet before being deepened to 2,500 feet to produce 110 barrels of oil a day from the Wilcox sands. Discoveries one year earlier in nearby Augusta had prompted El Dorado city fathers to seek a geological study of the area, according to Larry Skelton of the Kansas Geological Survey.

“Pioneers named El Dorado, Kansas, in 1857 for the beauty of the site and the promise of future riches but not until 58 years later was black rather than mythical yellow gold discovered when the Stapleton No. 1 oil well came in on October 5, 1915,” explained Lawrence Skelton in a 1997 USGS Journal article.

By 1914 interest was growing in Butler county and south central Kansas. “A few positive finds had been made, but nothing exciting,” Skelton noted in “Striking It Big in Kansas” for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG).

“Henry Doherty, founder of Cities Service in 1910, was seeking new gas reserves and opted for scientific exploration in lieu of wildcatting,” he wrote in the 2002 AAPG Explorer article.

After the 1915 El Dorado oilfield discovery, few companies would drill a well without first seeking the advice of a geologist, Photo courtesy Kansas Oil Museum.

Doherty hired geologists Charles Gould and Everett Carpenter in Oklahoma, sending them to Augusta, in Butler County. Gould had organized the Oklahoma Geological Survey in 1908 and served as its first director until 1911. According to Skelton, the geologists mapped prominent anticlinal structures in Permian Age limestone.

Finding Oil at Anticlines

By late 1914, several Augusta exploratory wells found commercial volumes of natural gas. Several wells also found oil. These developments “chafed El Dorado city fathers.”

According to geologist Skelton, about 15 miles northeast of Augusta, El Dorado had unsuccessfully searched for hydrocarbons since the 1890s. City leaders decided to hire Erasmus Haworth, the state geologist and chairman of the University of Kansas geology department.

“He mapped a large anticline on the same formations used by Gould and Carpenter at Augusta and selected a site that proved to be a dry hole,” Skelton explained.

Undeterred, Cities Service subsidiary Wichita Natural Gas bought the town’s 790 leased acres for $800, verified Haworth’s work and began drilling in late September 1915. The Stapleton No. 1 well found oil within a week.

“Using scientific geological survey methodology for the first time, Cities Service had identified a promising anticline,” Skelton noted. “His field work outlined the El Dorado Anticline.”

Butler County’s geologic revelations encouraged Gulf Oil, Standard Oil, and other companies to acquire leases around Augusta and El Dorado. In addition to Henry Doherty, industry leaders like Archibald Derby, John Vickers and William Skelly established successful El Dorado oil-producing and refining companies.

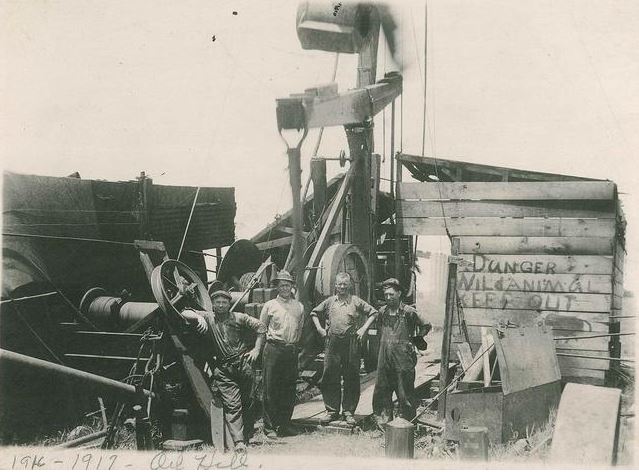

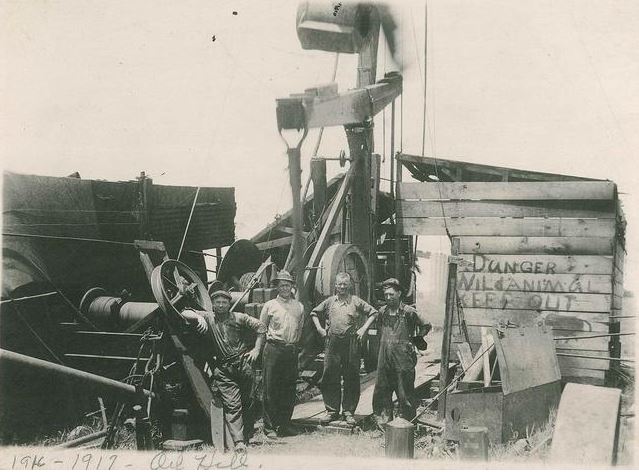

As Butler County wells multiplied, Oil Hill became the largest “company towns” in the world with some 8,500 residents. Photo courtesy Kansas Oil Museum.

“So the idea from that point forward, no oil company in the world would go and drill a well without seeking the advice of a geologist first,” proclaimed the executive director of the Kansas Oil Museum.

“Before 1915, geologists were seen in the same vein as witching and doodlebugs. They were just charlatans,” explained Warren Martin in a 2015 Butler County Times-Gazette article on the centennial of Stapleton No. 1 well.

“It fundamentally transformed it from that point going forward,” Martin added. “Geology was established as one of the great science industries.”

Also see Rocky Beginnings of Petroleum Geology.

Kansas Oil and Gas Boom

With the influx of thousands of workers, even Wichita accommodations were overwhelmed. Butler County’s population, about 23,000 in 1910, nearly doubled in 1920. To house its workers, Empire Gas & Fuel Company (formerly Wichita Natural Gas) built a 64-acre town northwest of El Dorado.

When the United States entered World War I, oil production escalated with the El Dorado field producing almost 29 million barrels of oil in 1918 — about nine percent of the nation’s oil.

The Kansas Oil Museum includes drilling and production equipment. The museum annually hosts a “Rockfest celebration of geology and oil and gas culture.” Photo by Bruce Wells

Although Oil Hill and its more than 8,000 residents, swimming pool, tennis courts and small golf course would disappear by the late 1950s, at the time it was called the largest “company town” in the world.

The Stapleton No. 1 well, which produced oil until 1967, can be visited by tourists — as can El Dorado’s Kansas Oil Museum, which includes 20 acres of rig displays, equipment exhibits and models of the region’s refinery history. The museum hosts events in an Energy Education Center, offers a variety of K-12 programs, and annually celebrates a “Rockfest” for aspiring geologists.

The Kansas museum’s pumping unit exhibits, the largest one on the grounds, educates visitors about evolving production technologies. It includes a 1970s pumpjack donated by Hawkins Oil Company. Visitors explore a variety of buildings depicting a typical petroleum boom town like Oil Hill.

The state’s earliest oil production began in 1892 at Neodesha in eastern Kansas — the first Kansas oil well — later proclaimed the first commercial discovery west of the Mississippi River.

A natural gas well along the Oklahoma border at Caney, ignited in 1906 and took five weeks to bring under control (see Kansas Gas Well Fire). In far western Kansas, the Hugoton Natural Gas Museum preserves the history of a multistate natural gas geologic formation.

_______________________________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2023 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Kansas Oil Boom.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/kansas-oil-boom. Last Updated: September 29, 2023. Original Published Date: October 4, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Aug 1, 2022 | Petroleum Companies

At the start of the 20th century, a growing number of Mid-Continent oilfields began their long history of oil discoveries. With them came the drilling boom and bust cycles of the U.S. petroleum industry. Major oilfield discoveries in North Texas during and after World War I, launched new, inexperienced ventures, including Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company

Although oil wealth would helped build Wichita Falls schools, infrastructure, hotels, banks, churches, and civic pride, competition increasingly made drilling prospects hard to come by. Oilfield equipment costs rose as excessive production lowered oil prices.

New oil exploration and production companies often arrived too late and went bankrupt without drilling single well. This did not discourage the rush for new investors (see Exploiting North Texas Fever).

A 1918 oil discovery near Wichita Falls joined earlier discoveries at Electra (1911) and Ranger (1917) to make Texas a worldwide leader in petroleum production.

The Texas Panhandle oil drilling boom began when the giant Ranger oilfield was discovered in October 1917 near Electra — where a 1911 shallow oilfield discovery already had attracted drillers. The “Roaring Ranger” well alone reached a daily production of 1,700 barrels of oil. The giant oilfield helped fuel the Allies’ victory in World War I.

Meanwhile, Conrad Hilton, who visited the Ranger area intending to buy a bank, saw the crowds of oilfield roughnecks and bought his first motel in nearby Cisco instead — learn more in Oil Boom Brings First Hilton Hotel.

Boom Town Burkburnett

Just outside Wichita Falls, at Burkburnett on July 29, 1918, a wildcat well erupted on S.L. Fowler’s farm just north of Wichita Falls near the Red River border with Oklahoma.

The new drilling boom made Burkburnett yet another famous American boom town. Two decades later it inspired the popular 1940 motion picture, “Boom Town,” which won an Academy Award. The oilfield drama featured Clark Gable (himself a former Oklahoma roughneck), Spencer Tracy, Claudette Colbert and Hedy Lamarr.

Even prior to the Burkburnett discovery, North Texas oilfields were producing half of all the state’s oil. Wichita Falls prospered and the town’s railroad line expanded. Refineries began to appear in 1915. That year Wichita County reported 1,025 producing wells.

In 1920 there were 47 factories within Wichita Falls. One year later the Wichita Falls and Southern Railroad Company added an extension for trains between Wichita Falls, Ranger and Fort Worth.

Sunshine State Oil & Refining

Among those rushing to the region’s boom towns was Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company, which incorporated in New Mexico on April 21, 1917. The new company set up its main operations in Wichita Falls capitalized at only $300,000.

Although Wichita Falls already hosted no less than nine competing independent refineries, the company built its own 3.5 miles north of town with an initial capacity of 1,250 barrels of oil a day that grew to 2,500 barrels of oil a day.

By 1920, Sunshine State Oil & Refining had increased capitalization to $650,000 and secured ownership of a 45-mile pipeline to connect with oil producers in the Burkburnett and Kemp-Munger-Allen fields.

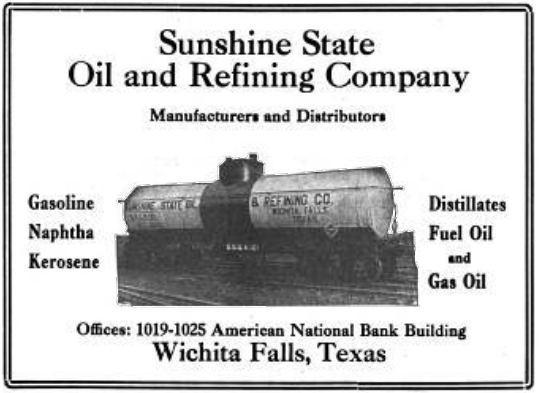

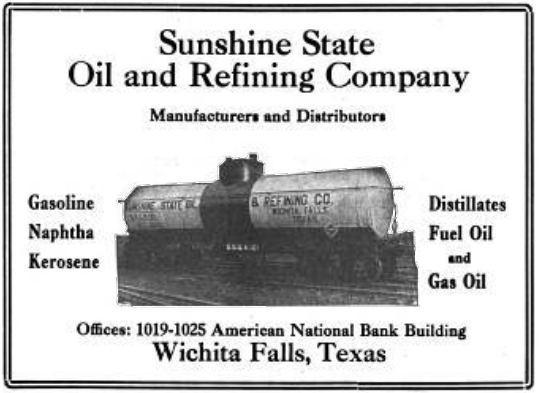

Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company had offices in the American National Bank Building in Wichita Falls, Texas.

By July 1922 the company marketed its brand of gasoline and kerosene in Wichita Falls, Burkburnett, Electra, and Gainsville. It also explored opportunities in Eddy and Chavez counties in New Mexico to secure further oil supplies.

The company sold its finished products, principally gasoline and kerosene, in railroad tank cars and managed a fleet that grew from 50 cars to 150 cars. “Manufacturers and Distributors – Gasolene, Naptha, Kerosene Distillates, Fuel Oil and Gas Oils,” proclaimed advertisements with the registered trade name of “Sunshine Special” for products.

Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company was reported to pay 100 percent dividends – but those dividends were paid in shares of company stock. To raise money, the company increased capitalization again and issued more stock.

However, a refining company’s margin for success was inevitably linked to the cost of crude oil and the price of refined petroleum products.

Sunshine State Oil & Refining sold its finished products in railroad tank cars and managed a fleet that grew from 50 cars to 150 cars.

Small independents faced additional challenges, as Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company President George C. Jensen would later note:

“The larger companies will pay posted price and the only way that the independent refineries are able to buy crude oil is to offer a large bonus, in some cases as much as 40 cents per barrel premium over prices paid by Standard Oil,” Jensen complained to Petroleum Magazine’s “Open Forum” readers. “They consequently cannot make a fair profit on refined products.”

Under these and other market pressures, Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company’s refinery began to operate well below capacity.

Sunshine sets in North Texas

As the drilling industry and the refineries competed, Wichita Falls prospered, thanks to “Black Gold.” The city added a municipal auditorium in 1927 and an airline passenger service in 1928 – the same year the city’s first commercial broadcasting station, KGKO, was established.

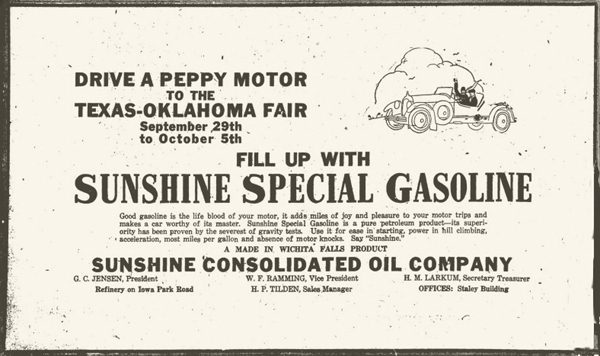

However, as early as July 1924 Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company was struggling with debt. The company issued more stock to raise capitalization to $1.5 million and in an agreement with shareholders changed its name to Sunshine Consolidated Oil Company.

Shareholders had to exchange their old stock certificates for the new Sunshine Consolidated Oil shares. The old Sunshine certificates were canceled. Efforts to sell new shares on the New York “curb market” did not fare well.

“Say Sunshine” advises this card for newly renamed but still financially troubled Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company and its “made in Wichita Falls product.”

As fundraising efforts failed, creditors forced the renamed company into receivership, which was contested but ultimately adjudicated by the 89th District Court in Texas. Assets were sold off to pay creditors. By November 5, 1925, the Corsicana Daily Sun reported:

A sale involving a cash consideration of $159,000 was consummated in the Wichita Falls oil district Wednesday when Bridwell & Heydrick closed a deal with receiver of the Sunshine Consolidated Oil Company whereby a number of leases in the Sunshine State and Freeman Hampton pools of Archer county changed hands.

After an intense and competitive seven years in business, Sunshine/Consolidated Oil Company failed, joining other oilfield ventures in the high-risk business of petroleum exploration, production and refining. The industry’s boom and bust cycles continue to this day.

North Texas petroleum prosperity began on April 1, 1911, when geyser of oil erupted at the Clayco No. 1 well at Electra,which would later be awarded the title of “ Pump Jack Capital of Texas.”

More stories of many exploration companies trying to join petroleum booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research in Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Join today as an AOGHS annual supporting member. Help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2022 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Sunshine State Oil & Refining Company.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/old-oil-stocks/sunshine-state-oil-refining-company. Last Updated: August 2, 2022. Original Published Date: July 22, 2018.

by Bruce Wells | Jul 1, 2015 | Petroleum Companies

Old Colony Oil Company began about the time the “Roaring Ranger” in Texas made national headlines in 1917 (see Oil Boom Brings First Hilton Hotel). The new company explored near Duncan, Oklahoma.

Despite production from its first two wells – a 20,000,000-cubic-foot-a-day “gasser” and a well producing 2,000 barrels oil oil a day from the Duncan field – Old Colony Oil Company failed to survive.

The company’s success in the Mid-Continent oilfield helped attract investors for funding additional lease purchases and exploratory drilling. The Mid-Continent’s potential had been revealed as early as 1892 (see First Kansas Oil Discovery). Old Colony Oil soon had operations in Texas, Oklahoma, Utah and Montana – but leasing and drilling costs coupled with a lack of consistent producers brought debt.

However, by 1922 the company’s fortunes had diminished to such a point it could only extract about 125 barrels a day from its nine remaining shallow wells in the diminishing Duncan oilfield.

With oil prices down, by May 1922 Old Colony Oil assets amounted to just $75,000 and the company was defaulting on $10,000 monthly payments due to the Wilkin-Hale Bank. Then the bank begin to fail (Wilkin and Hale of the Wilkin-Hale Bank were directors of the Old Colony Oil).

In the summer of 1922, Okahoma bank examiners investigated the interlocking directorates’ books. Hoping for the big oil strike to balance the ledgers, Wilkin-Hale Bank had used $200,000 worth of essentially worthless Old Colony Oil bonds in a transaction with the Consumers Bank of El Reno – and thereby sunk Wilkin-Hale, El Reno, and Old Colony Oil.

Obsolete Old Colony Oil stock certificates from the 1920s may have collectible value on eBay and “scripophily” websites. Such certificates sometimes are valued as artifacts from investors’ gambles on business ventures that failed.

Dry holes, market behavior, drilling costs, and a host of unpredictable hazards remain part of the high-risk, high-reward U.S. oil patch.

In 1947 experts from Halliburton and Stanolind companies applied a technology on a Duncan oilfield well – the the first commercial application of hydraulic fracturing. Learn more in Shooters – A “Fracking” History.

___________________________________________________________________________________

The stories of other exploration attempts to join petroleum exploration booms (and avoid busts) can be found in an updated series of research at Is my Old Oil Stock worth Anything?

Please support the American Oil & Gas Historical Society and this website with a donation. © AOGHS.