Oklahoma’s King of the Wildcatters

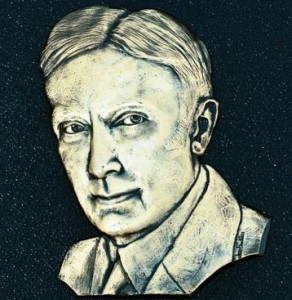

Oil derricks in the Oklahoma City Field in 1930 stood silent for one hour in tribute to Tom Slick.

Once known as “Dry Hole Slick,” wildcatter Thomas B. Slick discovered Oklahoma’s giant Cushing oilfield in 1912 and became known as the “King of the Wildcatters.” Today Cushing is the “Pipeline Crossroads of the World,” the trading hub for oil in North America – and the daily settlement point for prices, including West Texas Intermediate.

The owner of Spurlock Petroleum Company, Alexander Massey, enjoyed great success in the Kansas oilfields after finding oil or natural gas in 25 consecutive wells. In 1904, Massey hired an inexperienced 21-year-old “lease man” named Thomas Baker Slick for a 25 percent share in all the leases the young man could secure. They went to Tryon, Oklahoma, to look for oil.

When Oklahoma’s “King of the Wildcatters” Thomas B. Slick suddenly died from a stroke at age 46 in 1930, the oil derricks in the Oklahoma City field stood silent for one hour in tribute. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Massey later recalled that Slick, born in Shippenville, Pennsylvania, in 1883, showed a talent for securing petroleum leases. “Tom would go out and lease most of a territory as yet unproved or doubtful as to oil prospects,” Massey noted. “But he’d spread as clean a bunch of leases before a capitalist as you’d wish to see…He certainly knew what a good oil lease was.”

Spurlock Petroleum Company spudded an exploratory well on the farm of M.C. Teegarden near Tryon. As Slick continued securing leases that eventually totaled more than 27,000 acres, drilling generated excitement in the local newspaper and with other Oklahoma wildcatters.

Once known as “Dry Hole Slick” by many, on March 12, 1912, Thomas B. Slick discovered Oklahoma’s giant Cushing oilfield.

However, at a depth of 2,800 feet with no signs of oil, Spurlock Petroleum and owner Massey ran out of money. Tom Slick’s first well was a dry hole. It was the first of many.

Dry Hole Slick

In 1907, after another dry hole near Kendrick, Oklahoma, Slick left the employ of Massey and headed for Chicago, Illinois. Charles B. Shaffer of the Shaffer & Smathers Company hired Slick for $100 per month (and expenses) to find and secure promising oil leases.

Slick traveled to Illinois, Kentucky, western Canada, and eventually, back to Oklahoma. While leasing for Shaffer & Smathers, the young oilman drilled at least ten dry holes in Oklahoma, earning his unenviable nickname, “Dry Hole Slick.”

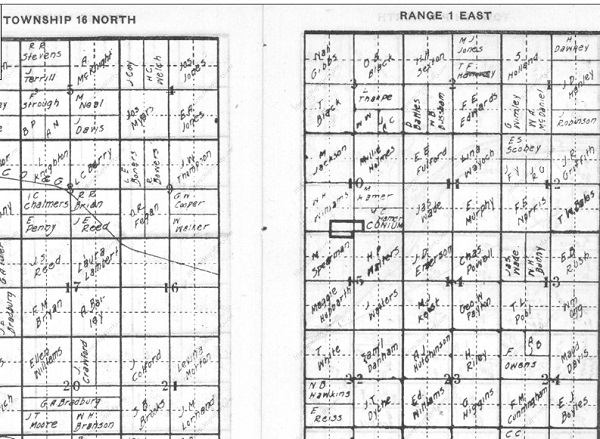

An example of township leases similar to those negotiated by Tom Slick, from the Atlas of North Central Oklahoma 1917 Oil Fields and Landowners: Oklahoma, M. P. Burke, 1917.

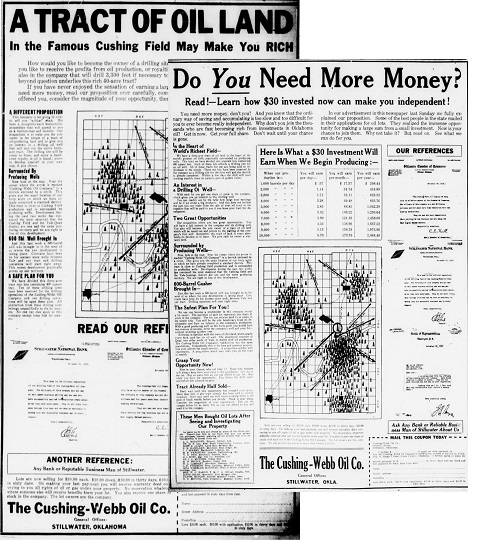

The Bristow Record newspaper reported that Slick, “continues to gamble on wild cat stuff. Few men have stuck to the wildcatting longer and harder than Slick and associates. It is said he has spent $150,000 mostly on dry holes.” Now also known as “Mad Tom” Slick, he tried his luck again just 35 miles down the road, in Cushing.

As “Mad Tom” pursued new leases in 1912, publications like the Cushing Independent encouraged readers to take advantage of leasing opportunities. “Land owners have everything to gain and no risk to themselves in making leases,” the newspaper reported on January 25.

“It costs from $8,000 to $10,000 to put down a single hole,” the newspaper noted. “Unless the promoters can get the leases they want they will not chance their money here, while other localities are eager to give leases and even bonuses in money to get prospecting done.”

The Cushing Democrat added, “We would repeat that we believe it to the best interests of the individuals and all that these leases be granted…And just a word of warning. If you make a lease see that the lessees name is not left blank, but that the name of Thomas B. Slick is there.”

Slick and Charles Shaffer spudded a wildcat well on the farm of Frank M. Wheeler in January 1912.

Cushing Gusher and Crafty Moves

On March 12, 1912, the Wheeler No. 1 well struck oil, producing about 400 barrels a day from a depth between 2,319 and 2,347 feet. It marked Tom Slick’s first gusher — and a giant oilfield discovery. Slick was so secretive about his find that he even cut the phone line to the Wheeler house to prevent word from spreading.

Knowing that exploration companies and speculators would descend in droves on the town once word got out, Slick protected his investment. Just how he did so would be described by a frustrated competing lease man to his boss:

You see, sir, Slick and Shaffer roped off their well on the Wheeler farm and posted guards and nobody can get near it…I got a call yesterday at the hotel in Cushing from a friend who said they had struck oil out there. A friend of his was listening in on the party line and heard the driller call Tom Slick at the farm where he’s been boarding and said they’d hit.

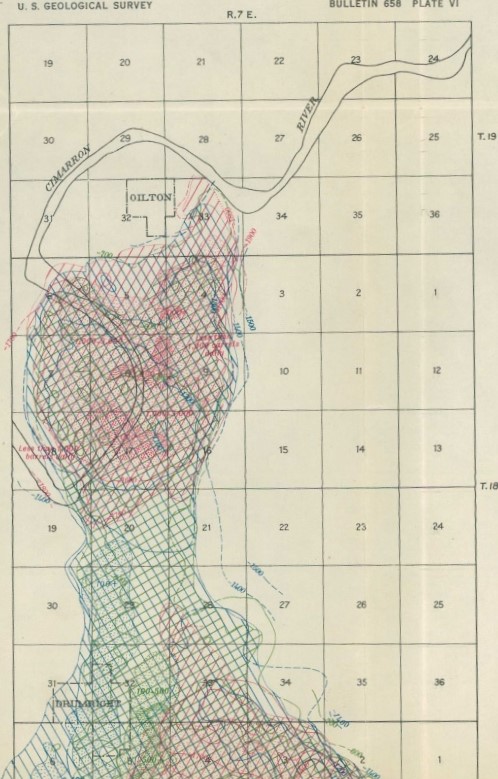

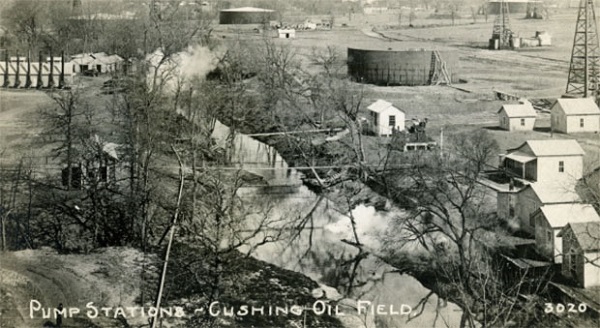

Pump stations in the Cushing oilfield, 1910-1918, from the Oklahoma Historical Society. More than 50 refineries once operated in the Cushing area about 50 miles west of Tulsa. Pipelines and storage facilities have since made it “the pipeline crossroads of the world.”

Well, I rushed down to the livery stable to get a rig to go out and do some leasing and damned if Slick hadn’t already been there and hired every rig. Not only there, but every other stable in town. They all had the barns locked and the horses out to pasture. There’s 25 rigs for hire in Cushing and he had them all for ten days at $4.50 a day apiece, so you know he really thinks he’s got something.

I went looking for a farm wagon to hire and had to walk three miles. Some other scouts had already gotten the wagons on the first farms I hit. Soon as I got one I beat it back to town to pick up a notary public to carry along with me to get leases — and damned if Slick hadn’t hired every notary in town, too.

Eleven days later the news had spread. As a leasing frenzy grew the Tryon Star reported, “Our old friend Tom Slick the oilman has struck it rich…Slick has been plugging away for several years and has put down several dry holes…He deserves this success and here’s hoping that it will make Tom his millions.”

New King of the Wildcatters

Tom Slick’s No. 1 Wheeler was the discovery well for the prolific Drumright-Cushing oilfield, which produced for the next 35 years, reaching 330,000 barrels every day at its peak.

Oklahoma’s Drumright Historical Society Museum includes the town’s 1915 Santa Fe Railroad Depot, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Slick was suddenly a very rich man. After his dramatic success in Drumright and Cushing, he began an incredible 18-year streak of discoveries in some of the nation’s most prolific oilfields. Visit the Drumright Historical Society Museum.

Slick was active in the Seminole Area, especially the oilfields of Pioneer, Tonkawa, Papoose, and Seminole. He secured leases and drilled wells that consistently paid off.

Slick’s oil gushers were spectacular: No. 4 Eakin — 10,000 barrels per day; No. 1 Laura Endicott — 4,500 barrels per day; No. 1 Walker — 5,000 barrels per day; No. 1 Franks — 5,000 barrels per day (see Greater Seminole Oil Boom).

Reflecting on his fortunes late in his career, he noted, “If I strike oil everyone calls it Tom Slick’s luck, (but) I call it largely judgment based upon experience. Some folks don’t recognize good luck when they meet it in the middle of the road. So I have been fortunate, or lucky, whichever you call it, but I’ve also done a lot of calling good luck to bring it my way.”

Newly discovered oilfields of the mid-1920s brought prosperity — and traffic jams — to Seminole, Oklahoma. Photo courtesy the Oklahoma Oil Museum.

Slick’s leases in Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas produced millions of barrels of oil. Production from his wells reached 35,000 barrels of oil a day 1929, and he was proclaimed the largest independent oil operator in the United States with a net worth estimated from $35 million and up to $100 million.

By 1930, in the Oklahoma City field alone, Slick had 45 wells being drilled, more than 30 wells completed, and the capacity to produce 200,000 barrels of crude daily. Across the Mid-Continent, stories of Tom Slick’s business acumen and integrity grew with his fortune.

It was often told how Slick once closed a $100,000 deal for a prized Seminole lease on a street corner. He met the owner on the street and inquired, “What do you want for that lease’ ‘A hundred thousand dollars,’ replied the owner. ‘It’s a sale, bring in your deeds,’ said Slick.”

Thomas B. Slick is among those honored at an outdoor plaza at the Sam Noble Museum, University of Oklahoma, in Norman.

Thomas B. Slick’s death from a stroke in August 1930 at the age of 46 abruptly ended a career that had helped supply an energy hungry nation with the petroleum it needed to grow.

“Oil derricks in the Oklahoma City Field stood silent for one hour in tribute,” reported the Oklahoma Historical Society. Slick’s biggest strike came a week after he died when his Campbell No. 1 well in Oklahoma City produced 43,200 barrels of oil per day.

Stories about the “King of the Wildcatters” and his oilfield discoveries would spread across the Mid-Continent. Thomas B. Slick, — no longer known as “Mad Tom” or “Dry Hole Slick” — joined other Oklahoma petroleum industry leaders honored at the Conoco Oil Pioneers of Oklahoma Plaza.

By the end of the 20th century, more than one-half million Oklahoma oil and natural gas wells were drilled since an oilfield discovery at Bartlesville in 1897 (learn more in First Oklahoma Oil Well).

More about Slick and his extraordinary oilfield career can be found King of the Wildcatters, the Life and Times of Tom Slick, 1883–1930 by Ray Miles, professor of history and dean of the college of liberal arts at McNeese State University, Lake Charles, Louisiana.

For example, Miles relates that in 1933, a friend and business partner of the Oklahoma wildcatter was kidnapped and held for ransom. Once released, Charles Urschel assisted the FBI in catching his abductors, including George “Machine Gun” Kelly, who was sentenced to life in Alcatraz.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: King of the Wildcatters, the Life and Times of Tom Slick, 1883–1930. (2004); The Oklahoma City Oil Field in Pictures (2005); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry

(1980). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Become an AOGHS annual supporting member and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2024 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oklahoma’s King of the Wildcatters.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/wildcatter-tom-slick. Last Updated: December 30, 2023. Original Published Date: December 1, 2004.