by Bruce Wells | Sep 18, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Pico Canyon oilfield brought pipelines, refineries, and Chevron.

Following the 1859 first commercial U.S. oil discovery in Pennsylvania, the earliest petroleum exploration companies were attracted to California’s natural oil seeps. Small but promising discoveries after the Civil War led to the state’s first gusher in 1876 — and the launching of a new California industry.

Pico Canyon, less than 35 miles north of Los Angeles, produced limited amounts of oil as early as 1855, but there was no market for the petroleum found near natural oil seeps. The first California drilling boom arrived a decade later in the northern part of the state with an oilfield also found near seeps.

Humboldt County Oil

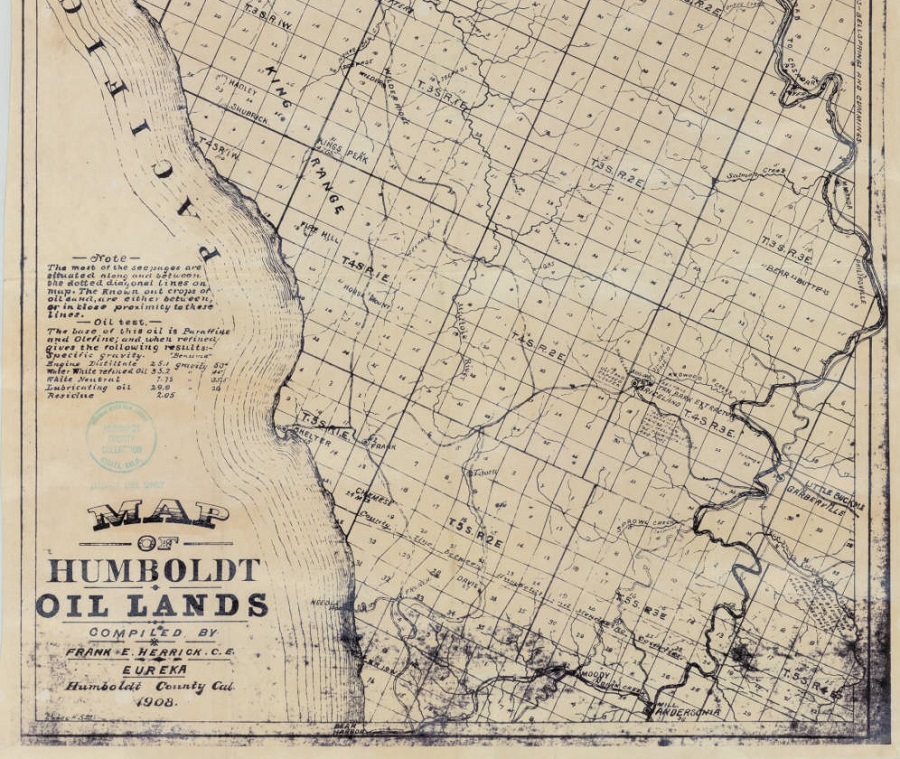

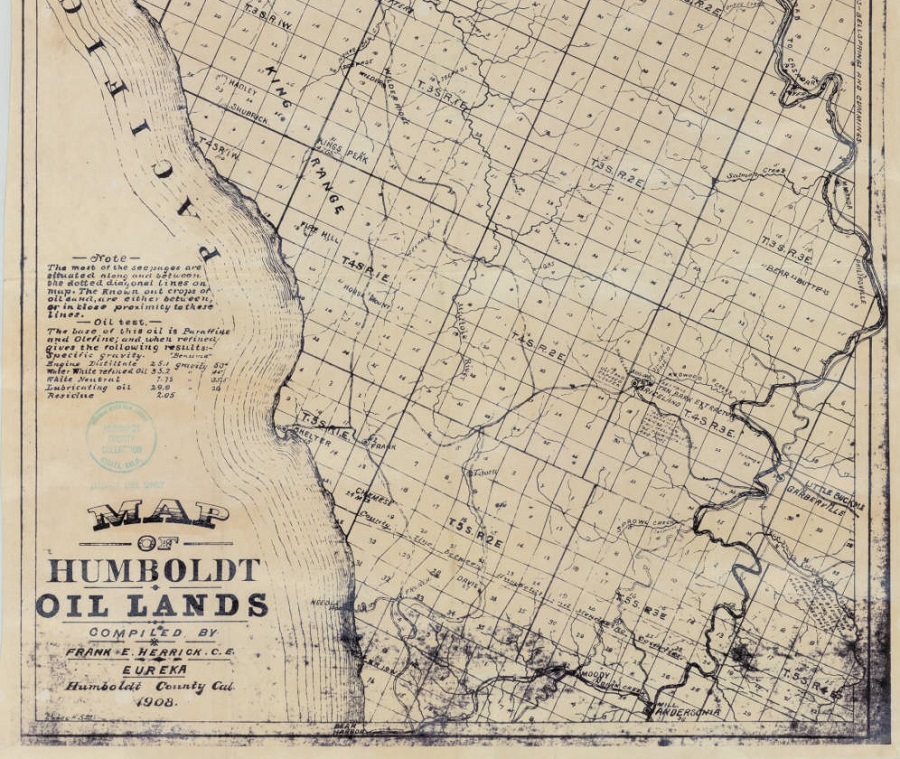

Completed in 1865 by the Old Union Matolle Oil Company, the Humboldt County well produced oil near the aptly named Petrolia. The oilfield discovery quickly attracted some of America’s earliest exploration companies.

Detail of a 1908 “Map of Humboldt County Oil Lands” includes post-Civil War commercial oil wells that attracted more drilling to northern California. Map courtesy Humboldt County Map Collection, Cal Poly Humboldt Library Special Collection.

A California historical marker (no. 543) dedicated on November 10, 1955, declared:

California’s First Drilled Oil Wells — California’s first drilled oil wells producing crude to be refined and sold commercially were located on the north fork of the river approximately three miles east of here. The Old Union Mattole Oil Company made its first shipment of oil from here in June 1865 to a San Francisco refinery. Many old wellheads remain today.

Although the “Old Union well” initially yielded about 30 barrels of high-quality oil, production declined to one barrel of oil per day, and the prospect was abandoned, according to K.R. Aalto, a geologist at Humboldt State University.

The Humboldt County well in what became the oilfield “attracted interest and investment among oilmen because of the abundance of oil and gas seeps throughout that region,” Aalto noted in his 2011 article in Oil-Industry History. But the California petroleum industry truly began to the south, at Pico Canyon Oilfield, a few miles west of Newhall.

Pico Canyon Well No. 4

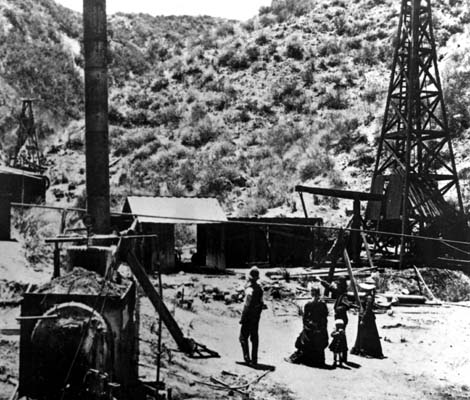

In Pico Canyon of the Santa Susana Mountains, Charles A. Mentry (1847-1900), who had formed a partnership establishing the California Star Oil Works Company, drilled three exploratory wells between 1875 and 1876. All showed promise, and the first West Coast oil gusher arrived with his fourth well. The oilfield discovery would lead to the creation of a major oil company.

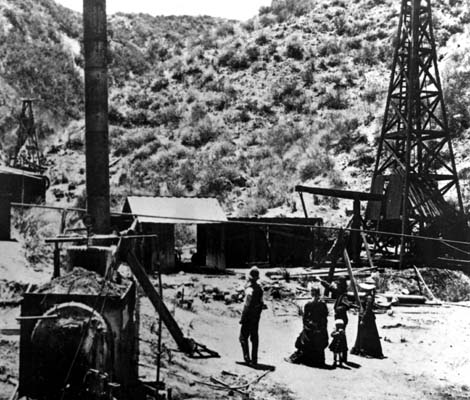

The steam boiler and cable tools, including the “walking beam,” of Pico Well No. 4 in 1877. Photo by Carleton Watkins courtesy Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

Drilling with a steam-powered cable-tool rig in an area known for its many oil seeps, Mentry discovered the Pico Canyon oilfield north of Los Angeles. California’s first truly commercial oil well, the Pico Well No. 4 gusher of September 26, 1876, prompted more development, including pipeline construction and an oil refinery for producing kerosene.

According to an article in the Los Angeles Times, the well initially produced 25 barrels a day from 370 feet. Mentry improvised many of his cable tools, including making a drill stem out of old railroad car axles he welded together.

“The railroad had not then been completed, there was no road into the canyon, water was almost unattainable, and there were no adequate tools or machinery to be had,” noted the Times article.

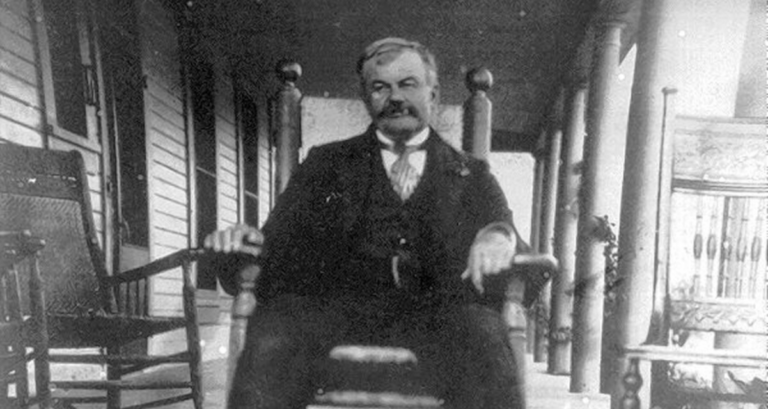

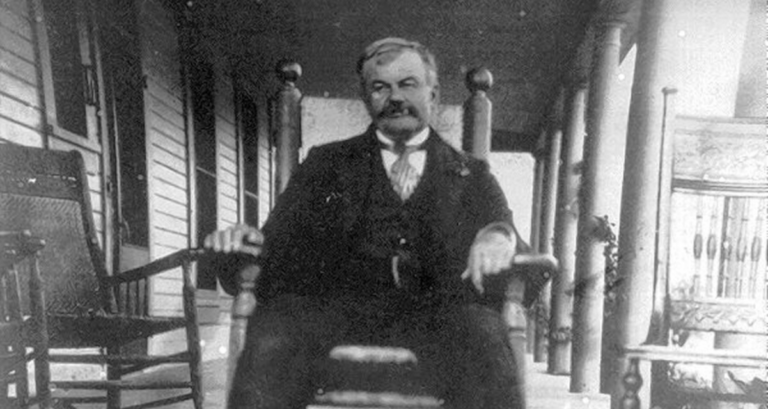

Charles Mentry had already successfully drilled 42 wells near Titusville, Pennsylvania, before exploring in the Santa Clara Valley — and launching California’s petroleum industry. Photo courtesy KHTS Radio, Santa Clara.

Mentry persevered, and his success in Pico Canyon led to the founding of “Mentryville,” the onetime drilling boom town that is today the site of Stevenson Ranch.

“Although his life was tragically cut short by illness on October 4, 1900, from typhoid fever, Mentry’s legacy as a pioneer in California’s oil industry endures,” noted KHTS Radio, Santa Clara. “His work in Pico Canyon not only made him a key figure in the region’s development but also set the stage for California’s future as an oil-rich state,” KHTS reported in 2025.

Visit the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society website to learn more Pico Canyon petroleum exploration and production history.

First Refinery

California Star Oil Works deepened the well to 560 feet, increasing daily production by 125 barrels, and constructed its pipeline from Pico Canyon to the newly built refinery in Newhall, just south of Santa Clarita.

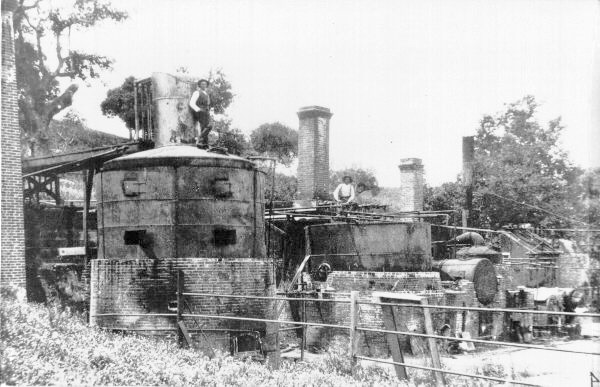

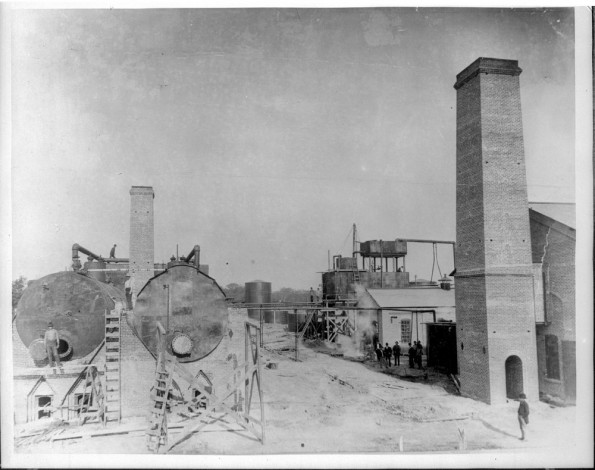

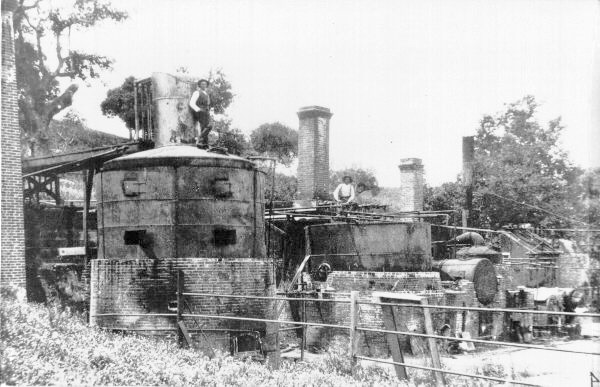

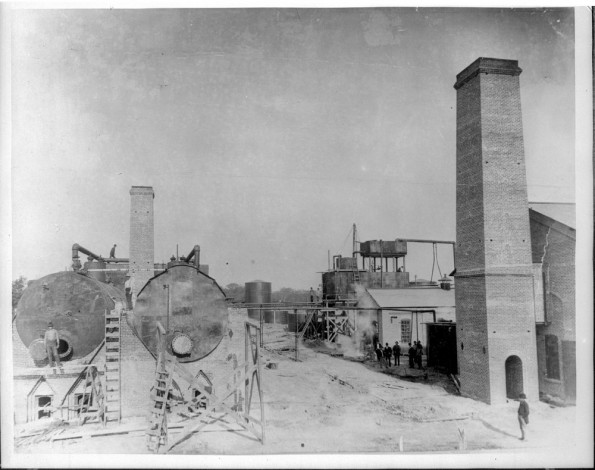

By 1880, California’s first commercial refinery processed oil from its first commercial oil well to make kerosene and other products. Photo courtesy the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

Producing kerosene and lubricants, Newhall’s Pioneer Refinery on Pine Street would become the first successful commercial refinery in the West. Giant stills set on brick foundations included two capable of producing 150 barrels a day each. The city of Santa Clarita received California’s first successful refinery as a gift from Chevron in 1997.

The Santa Clarita refinery, today preserved as a tourist attraction, is among the oldest in the world. The major oil company can trace its beginnings to the 1876 Pico Canyon oil well, which has been designated a historic site by the California Office of Historic Preservation.

Chevron Corporation, once the Standard Oil Company of California, in 1900 acquired Pacific Coast Oil Company. Pacific Coast had become majority owner of California Star Oil Works in 1879.

Santa Clarita acquired California’s first refinery as a gift from Chevron in 1997. It is one of the oldest existing oil refinery sites in the world. Photo by Konrad Summers.

Refining Kerosene for Lamps

California’s commercial refineries were among the first in America, where the industry began with small refineries in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, producing kerosene for lamps. The oil came from Titusville area oilfields — and a giant 1871 field discovered at Bradford, about 70 miles to the northeast.

The Bradford oilfield, which became known as America’s “first billion-dollar oilfield,” launched many Pennsylvania refineries, including the still-operating American Refining Group. The field’s first well produced just 10 barrels a day from 1,110 feet.

By 1875. Bradford leases reached as high as $1,000 per acre. A decade later, a sudden decline in the oilfield’s production led to a technological breakthrough. Pioneers in the new science of petroleum geology suggested that water pressure on oil sands could be used to increase oil production — “waterflooding” the geologic formation.

The oldest operating U.S. oil refinery began in 1881 in Bradford, Pennsylvania.

In Neodesha, Kansas, the Norman No. 1 well of 1892 revealed a petroleum-rich geologic region that would extend across Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana. Standard Oil built a refinery in Neodesha in 1897 that refined 500 barrels of oil a day. Standard was the first to process oil from the giant Mid-Continent field (learn more in Kansas Well reveals Mid-Continent).

In 2024, there were 134 operable petroleum refineries in the United States, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The newest refinery with significant downstream capacity — a facility in Garyville, Louisiana — came online in 1977.

Built in 1897, a Standard Oil refinery in Neodesha, Kansas, refined 500 barrels of oil per day – the first to process oil from the Mid-Continent field. From “Kansas Memory” collection of the Kansas Historical Society.

For an investigation into which California oil well was the first, see this 2011 SearchReSearch blog of Dan Russell.

Learn more California petroleum history in the Signal Hill Oil Boom.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: California State University, Dominguez Hills (2010); Pico Canyon Chronicles: The Story of California’s Pioneer Oil Field

(2010); Pico Canyon Chronicles: The Story of California’s Pioneer Oil Field (1985). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1985). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information: Article Title: “First California Oil Well.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/first-california-oil-well. Last Updated: September 17, 2025. Original Published Date: September 9, 2015.

by Bruce Wells | Jul 22, 2025 | Energy Education Resources

California oil seeps created asphalt pools — not tar — that trapped Ice Age animals.

The sticky black pools attracting tourists between Beverly Hills and downtown Los Angeles are natural asphalt, also known as bitumen. Although the repetitive tar pits’ name has stuck, the seeps are part of America’s oil history.

The La Brea site — discovered by a Spanish expedition on August 3, 1769 — originated from naturally produced California oil seeps found onshore and offshore. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Jun 19, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Cemetery generated royalty checks to next-of-kin when oil was drawn from beneath family plots.

In the summer of 1921, the Signal Hill oil discovery would help make California the source of one-quarter of the world’s entire oil output. Soon known as “Porcupine Hill,” the town’s Long Beach oilfield produced about 260,000 barrels of oil a day by 1923.

The Alamitos No. 1 well, drilled on a remote hilltop south of Los Angeles, erupted a column of “black gold” on June 23, 1921. Natural gas pressure was so great that the oil geyser climbed 114 feet into the air.

After the June 1921 oilfield discovery, Signal Hill had so many derricks that people called it Porcupine Hill. Circa 1935 postcard courtesy Boston Public Library, Digital Commonwealth.

The oilfield discovery well, which produced almost 600 barrels a day, would eventually produce 700,000 barrels of oil. Signal Hill incorporated three years after its Alamitos discovery well made headlines.

In 1923, Signal Hill’s petroleum field produced more than 68 million barrels of oil. The community of Signal Hill later became one of the first U.S. cities to be surrounded by another city, Long Beach.

Signal Hill, a residential area before the 1921 discovery of the Long Beach oilfield, became covered in derricks. “Today you can see wonderful commemorative art displays of this era throughout the lush parks and walkways of Signal Hill,” notes a local newspaper.

By the 2000s, more than one billion barrels of oil were pumped from the Long Beach oilfield since the original 1921 strike. “Signal Hill is the scene of feverish activity, of an endless caravan of automobiles coming and going, of hustle and bustle, of a glow of optimism,” reported California Oil World.

Signal Hill circa 1930 — at the corner of 1st Street and Belmont Street. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Museum of Natural History.

“Derricks are being erected as fast as timber reaches the ground,” the magazine adds. “New companies are coming in overnight. Every available piece of acreage on and about Signal Hill is being signed up.”

Signal Hill helped make California the source of one-quarter of the world’s oil. “Porcupine Hill” and the Long Beach field produced 260,000 barrels of oil a day by 1923.

Within a year, Signal Hill — before and after a residential area — will have 108 wells, producing 14,000 barrels of oil a day. There were so many derricks, people started calling it Porcupine Hill. “Derricks are so close that on Willow Street, Sunnyside Cemetery graves generated royalty checks to next-of-kin when oil was drawn from beneath family plots,” noted one historian.

Derricks were so close to one cemetery that graves “generated royalty checks to next-of-kin when oil was drawn from beneath family plots.” By 1923, production would reach 259,000 barrels per day from nearly 300 wells. Photo is part of a panorama in the Library of Congress.

Dave Summers explained in his 2011 article, “The Oil Beneath California,” that when oilfields around Los Angeles began to develop, “Californian production became a significant player on the national stage.” The OilPrice.com article continued:

By 1923 it was producing some 259,000 barrels per day from some 300 wells, in comparison with Huntington Beach, which was then at 113,000 barrels per day and Santa Fe Springs at 32,000 barrels per day… And, in a foreboding of the future problems of overproduction, this was the first year in a decade that supply exceeded demand.

Shell Oil Geologists

Signal Hill oil potential had drawn wildcatters south of Los Angeles since 1917 but with no success. Two Royal Dutch Shell Oil Company geologists and a driller persevered.

“This was a great exploit and economic risk for the time. Shell Oil Company had just lost $3 million at a failed drilling site in Ventura, five years before,” reported a Long Beach newspaper.

A 1954 photograph of the Alamitos No. 1 well — and the monument dedicated on May 3, 1952, “as a tribute to the petroleum pioneers for their success here…”

Although another “dry hole” would be expensive, Shell geologists Frank Hayes and Alvin Theodore Schwennesen spudded their well in March 1921. Driller O.P. “Happy” Yowells believed oil lay deeper than earlier “dusters” had attempted to reach.

By summer the steam-powered cable tool rig had Yowells close to making oilfield history. On June 23, 1921, at a depth of 3,114 feet, his wildcat well for Shell Oil erupted, revealing a petroleum reserve that extended to nearby Long Beach.

According to the Paleontological Research Institution, Signal Hill became the biggest oil field the already productive Southern California region had ever seen. This made California, “the nation’s number-one producing state, and in 1923, California was the source of one-quarter of the world’s entire output of oil!”

Decades before Signal Hill, another giant southern California oilfield had been discovered in 1892. A struggling prospector drilled into tar seeps he found near present-day Dodger Stadium (see Discovering Los Angeles Oilfields).

Signal Hill Oil Park

Today, Signal Hill’s Discovery Well Park includes a community center to educate the public. Historic photos and descriptions can be found at six viewpoints along the Panorama Promenade. There are producing oil wells throughout the hill — with the historic “Discovery Well, Alamitos Number 1” at the corner of Temple Avenue and East Hill Street.

A monument dedicated on May 3, 1952, serves “as a tribute to the petroleum pioneers for their success here, a success which has, by aiding in the growth and expansion of the petroleum industry, contributed so much to the welfare of mankind.”

Visitors to the area can see “wonderful commemorative art displays of this era throughout the lush parks and walkways of Signal Hill,” reported the Long Beach Beachcomber. Dedicated on September 30, 2006, the statue “Tribute to the Roughnecks” can be found on Skyline Drive.

“Tribute to the Roughnecks” by Cindy Jackson stands atop Signal Hill. Long Beach is in the distance. Signal Hill Petroleum Chairman Jerry Barto and Shell Oil employee Bruce Kerr are depicted in bronze.

The first California oil wells were drilled near oil seeps in the northern part of the state around the time of the Civil War. These Pico Canyon wells produced limited amounts of crude oil, but there was no market for the oil. Larger oilfields would be revealed in the early 1890s about 35 miles to the south.

Earlier explorers noted evidence of California’s petroleum fields by the large number of oil seeps, both onshore and offshore. California’s first commercial oil well in 1876 was drilled in Pica Canyon, well known for its asphalt seeps.

Between 1913 and 1923 Hollywood used the derricks on Signal Hill in movies starring Buster Keaton and Fatty Arbuckle. In 1957, what many consider the world’s first “all jazz” radio station, KNOB (now KLAX), first transmitted from a small studio on top of the historic oil hill.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Signal Hill, California, Images of America (2006); Huntington Beach, California, Postcard History Series

(2006); Huntington Beach, California, Postcard History Series (2009); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry

(2009); Black Gold in California: The Story of California Petroleum Industry  (2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Signal Hill Oil Boom.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-pioneers/signal-hill-oil/. Last Updated: June 18, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | May 19, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

May 19, 1885 – Lima Oilfield discovered in Ohio –

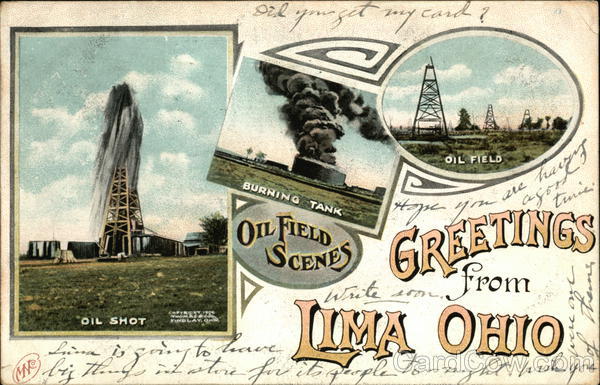

Ohio’s petroleum industry began when Benjamin Faurot found oil at Lima in the northwestern part of the state. He had been searching for natural gas in the prolific Trenton Rock Limestone (see Indiana Natural Gas Boom). “If the well turns out, as it looks now that it will, look out for the biggest boom Lima ever had,” proclaimed Lima’s Daily Republican newspaper.

A 1919 postcard published by Robbins Bros., Boston, promotes the oil wealth of Lima, Ohio, with derricks, an oil gusher, and a burning oil tank.

Faurot organized the Trenton Rock Oil Company, and by 1886 the Lima oilfield was producing more than 20 million barrels of oil, the most in the nation. The Lima field’s heavy oil needed special refining, and Standard Oil Company of New Jersey in 1889 began construction on the Whiting refinery.

Learn more in Great Oil Boom of Lima, Ohio.

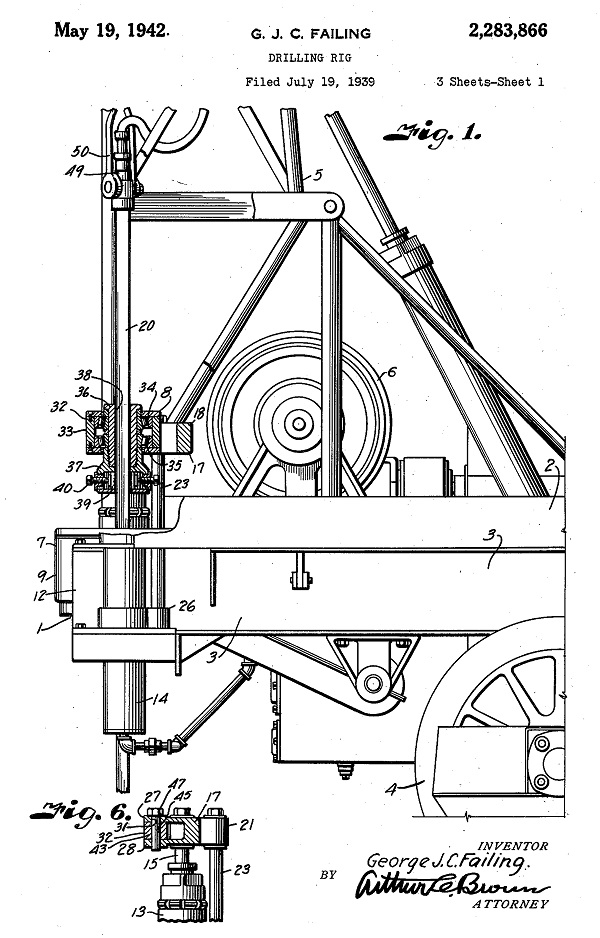

May 19, 1942 – Oklahoma Inventor patents Portable Drilling Rig

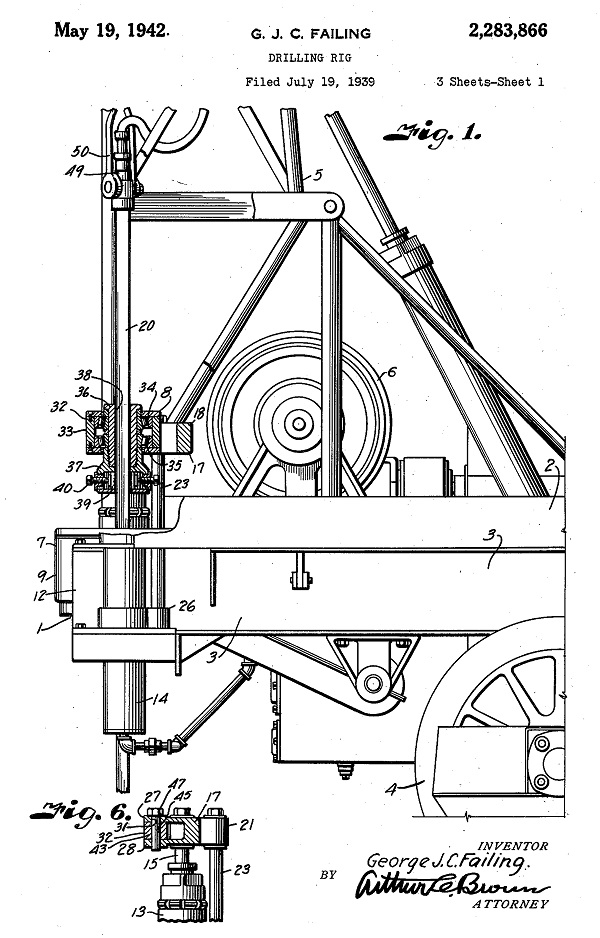

A pioneer in oilfield technologies, George E. Failing of Enid, Oklahoma, received a patent for his design of a drilling rig on a truck bed. “I designate the rear portion of a drilling rig such as used in drilling shallow wells, the taking of cores, drilling of shot-holes, and performing similar oil field operations,” Failing noted in his patent.

In 1931, he had mounted a rig on a 1927 Ford farm truck, “adding a power take-off assembly to transfer power from the truck engine to the drill,” according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. Failing would receive more than 300 patents for oilfield tools, “from rock bit cores to an apparatus for seismic surveying.”

George Failing’s rig design — powered by a pickup truck’s engine — proved ideal for rapidly drilling slanted wells.

Failing’s portable rig could drill ten slanted, 50-foot holes in a single day, while a traditional rotary rig took about a week to set up and drill to a similar depth. He demonstrated his portable drilling technology at a 1933 well disaster in Conroe, Texas, working with H. John Eastman, today considered the father of directional drilling (see Technology and the “Conroe Crater”).

May 19, 1969 – First Offshore Technology Conference

Houston’s largest convention and tradeshow, the Offshore Technology Conference, began in response to “growing technological needs of the global ocean extraction and environmental protection industries,” according to History of OTC. In 2013, more than 2,700 companies exhibited in “an area equivalent to 10 U.S. football fields.”

Since 1969, the conference has generated more than $3.2 billion for Houston. OTC Brasil was launched in 2011 along with an Arctic Technology Conference (2011-2016). OTC Asia was launched in 2012. The next Houston OTC will take place May 4-7, 2026.

May 20, 1930 – Geophysicists establish Professional Society

Earth scientists in Houston established the Society of Economic Geophysicists to encourage the ethical practice of geophysics in the exploration and development of natural resources. The organization in 1937 adopted the name Society of Exploration Geophysicists (SEG), which in 2024 reported 14,000 members in 114 countries.

The Doodlebugger by Oklahoma sculptor Jay O’Melia has welcomed visitors to SEG headquarters since 2002. Photo by Bruce Wells.

SEG’s journal Geophysics began publishing in 1936 with articles on exploration technologies, including seismic, gravity, and magnetic imaging. The journal warned of hucksters using vague or unproven properties of oil and geological formations. At its Tulsa headquarters in 2002, SEG unveiled The Doodlebugger, a 10-foot bronze statue by Oklahoma sculptor Jay O’Melia, who also sculpted the Oil Patch Warrior, a World War II memorial.

May 21, 1923 – “Esso” first used by Standard Oil Company

For the first time, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey used “Esso” to market the company’s “refined, semi-refined, and unrefined oils made from petroleum, both with and without admixture of animal, vegetable, or mineral oils, for illuminating, burning, power, fuel, and lubricating purposes, and greases.”

Standard Oil of New Jersey logo, 1923 to 1934, when text became plainer and inside an ellipse.

In 1923, Esso — the phonetic spelling of the abbreviation “S.O.” for Standard Oil — became a registered trademark. The future children’s book author Theodor Geisel — Dr. Seuss — began drawing Essolube product ads in the 1930s. Exxon (now ExxonMobil) removed its U.S. Esso brand in 1973.

May 23, 1905 – Patent issued for Improved Metal Barrel Lid

Henry Wehrhahn, superintendent for the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company of Brooklyn, New York, received the first of two 1905 patents that presaged the modern 55-gallon oil drum. The first design included “a means for readily detaching and securing the head of a metal barrel.”

Wehrhahn assigned his patent rights to the widow of Robert Seaman, founder of Iron Clad Manufacturing, Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman — journalist Nellie Bly. In December 1905, Wehrhahn also assigned her the rights to his improved metal barrel patent.

Learn more in Remarkable Nellie Bly’s Oil Drum.

May 23, 1937 – Death of World’s Richest Man

Almost 70 years after founding Standard Oil Company in Ohio and 40 years after retiring from the company in 1897, John D. Rockefeller died in Ormond Beach, Florida, at age 97. His petroleum empire had peaked in 1912.

Born on July 8, 1839, in Richford, New York, Rockefeller attended high school in Cleveland, Ohio, from 1853 to 1855. He became an assistant bookkeeper with a produce shipping company before forming his own company in 1859 — the same year of the first U.S. oil well in Pennsylvania. Rockefeller was 24 in 1865 when he took control of his first refinery, which would be the largest in the world three years later.

John Rockefeller, 1839-1937. Photo courtesy of Cleveland State University.

By the time his petroleum fortune peaked at $900 million in 1912 ($29.7 billion in 2025 dollars), Rockefeller’s philanthropy was well known. His unprecedented wealth funded the University of Chicago, the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, (now the Rockefeller Foundation), and Spelman College in Atlanta.

May 24, 1902 – Oil & Gas Journal published

Holland Reavis founded the Oil Investors’ Journal In Beaumont, Texas, to report on financial issues facing operators and investors in the giant oilfield discovered nearby one year earlier at Spindletop Hill. Reavis sold his semimonthly publication to Patrick Boyle of Oil City, Pennsylvania, in 1910.

Norman Rockwell illustrated a 1962 ad promoting the Oil and Gas Journal.

Boyle, a former oilfield scout and publisher of the Oil City Derrick, increased publication frequency to weekly and renamed it the Oil & Gas Journal. Following his death in 1920, son-in-law Frank Lauinger moved operations to Tulsa and further expanded the company, which became PennWell Publishing in 1980. The Derrick newspaper in Oil City, which began in 1885, continues to be published by the Boyle family.

May 24, 1920 – Huntington Beach Oilfield discovered in California

A Standard Oil Company of California exploratory well discovered the Huntington Beach oilfield. The beach town’s population grew from 1,500 to 5,000 within a month of the well drilled at Clay Avenue and Golden West Street.

A forest of derricks crowd the Huntington Beach in 1926. The giant oilfield produced more than 16 million barrels of oil in 1964 alone and totaled more than one billion barrels by 2000. Photo courtesy Orange County Archives.

The field had 59 producing wells with daily production of 16,500 barrels of oil by November 1921. The activity brought national attention to Huntington Beach and renewed interest in the Los Angeles City oilfield.

By 2000, the giant oilfield had produced more than one billion barrels of oil, according to the Orange County Register, which noted that as production peaked, “the pressure of explosive population growth began pushing the wells off land that had become more valuable as sites for housing.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Ohio Oil and Gas (2008); History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Careers in Geophysics

(2007); Careers in Geophysics (2017); Offshore Pioneers: Brown & Root and the History of Offshore Oil and Gas

(2017); Offshore Pioneers: Brown & Root and the History of Offshore Oil and Gas (1997); A Geophysicist’s Memoir: Searching for Oil on Six Continents

(1997); A Geophysicist’s Memoir: Searching for Oil on Six Continents (2017); Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist

(2017); Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist (1994); Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

(1994); Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (2004); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery

(2004); Giant Under the Hill: A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery (2008); Huntington Beach, California, Postcard History Series

(2008); Huntington Beach, California, Postcard History Series (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an annual AOGHS supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 10, 2025 | Petroleum Pioneers

Natural oil seeps, giant oilfields, and the beginning of the California petroleum industry.

“Everyone thinks of Los Angeles as the ultimate car city, but the city’s relationship with petroleum products is far more significant than just consumption.” — Center for Land Use Interpretation

When struggling prospector Edward L. Doheny and his mining partner Charles Canfield decided to dig a well in 1892, they chose a site already known for its “tar” pools that bubbled to the surface. (more…)

(2010); Pico Canyon Chronicles: The Story of California’s Pioneer Oil Field

(1985). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.