Yellow Dog – Oilfield Lantern

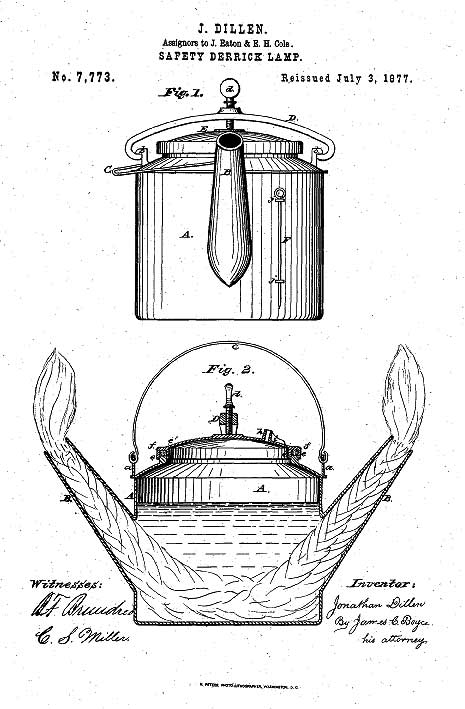

A two-wicked safety lamp for preventing “destructive conflagrations” on oil derricks.

Oil patch lore says “Yellow Dog” lanterns got their name because of two burning wicks that resembled a dog’s glowing eyes at night. Others say the lamps cast an eerie dog’s head shadow on the derrick floor.

Rare is the community oil museum that doesn’t have a Yellow Dog in its collection. Officially patented a decade after the Civil War, the two-wicked “Derrick Safety Lamp” would become an oilfield icon. But long before Yellow Dogs found their way to the oil patch, a similar design burned animal fat atop America’s lighthouses.

First patented in 1870, Jonathan Dillen’s lantern was “adapted for use in the oil regions…where the explosion of a lamp is attended with great danger by causing destructive conflagration and consequent loss of life and property.”

By the late 1700s, the cylindrical “Bucket Lamp” included two or four spouts protruding from its sides, according to Thomas Tag in Lighthouse Lamps Through Time. “Each spout carried a large diameter rope wick that extended down inside the body of the lamp into the oil.”

As late as 1874, four years after the Yellow Dog lamp’s patent, the U.S. Lighthouse Board of the Department of Treasury continued to mandate the use of lard for fueling the beacons, later rejecting electricity and natural gas because of “the complexity and cost of the apparatus.”

By 1877, the Lighthouse Board changed its illumination mandate to kerosene, which would be supplanted by electric arc lamps and followed by incandescent bulbs.

Inventing the Yellow Dog

Despite its many oilfield service manufacturers, the Yellow Dog’s origins remain in the dark. Some historical sources claim the derrick lamp’s design originated with the whaling industry, but neither the Nantucket nor New Bedford whaling museums have found any such evidence.

Railroad museums often include collections of cast iron smudge pots, but nothing approaching the heavy, crude-oil-burning lanterns once prevalent in oilfields from Pennsylvania to California.

Inventor Jonathan Dillen of Petroleum Centre, Pennsylvania, was first to patent what became the iconic lantern of the early years of the petroleum industry. His U.S. patent was awarded on May 3, 1870. The two-wicked lamp joined other safety innovations as drilling technologies evolved.

The lamp was designed “for illuminating places out of doors, especially in and about derricks, and machinery in the oil regions, whereby explosions are more dangerous and destructive to life and property than in most other places.”

“My improved lamp is intended to burn crude petroleum as it comes from the wells fresh and gassy,” Dillen proclaimed. “It is to be used, mainly, around oil wells, and its construction is such as to make it very strong, so that it cannot be easily broken or exploded.”

Dillen’s Yellow Dog patent was improved upon and reissued in 1872 and again in 1877 when it was assigned to a growing oilfield equipment supplier.

Oil Well Supply Company

In 1861, John Eaton made a business trip to the booming oil region of western Pennsylvania. Within a few years, he had set up his own business with Edward Cole. With the addition of Edward Burnham, the company grew to become a preeminent supplier of oilfield equipment.

A John Eaton biography by his great-grandson notes Eaton was considered “the father of the well supply trade” of early Pennsylvania oilfields.

By 1877, Eaton, Cole & Burnham oilfield supply had outlets in the Pennsylvania oil regions, including Pittsburgh and Bradford. The company changed its name Oil Well Supply Company the next year, according to a biography by his great-grandson, Louis B. Fleming.

“The first goods manufactured by the Oil Well Supply Company were made on a foot lathe,” John Eaton would recall. The oilfield equipment supply company was operating 75 manufacturing plants by the turn of the 20th century.

The biography, John Eaton, by journalist Fleming, cited the classic 1898 book Sketches in Crude Oil, which noted that Oil Well Supply company’s founder and president “may fairly claim to be the father of the well supply trade.”

A Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission roadside marker erected in Oil City in 1992 notes: “Oil Well Supply Company — Founded nearby in 1878, it was a leading manufacturer of oil well machinery and supplies, serving the oil industry across the globe. By the early 1900s, employment peaked at 2,000. In 1930 it became a subsidiary of United States Steel.”

Incorporated in Pennsylvania — the Keystone State — Forest Oil’s logo features the iconic two-wicked lamp invented in 1870.

In Oil City at its 45-acre Imperial Works on the Allegheny River, Oil Well Supply manufactured oilfield engines and “cast and malleable iron goods” that included the two-wicked derrick safety lamp. The 1884 Oil Well Supply catalog listed Yellow Dog lamps at $1.50 each.

Today, along with their shadowy origins, the Yellow Dog lanterns are relegated to museums, antique shops and collectors. They sometimes can be found on display next to another unusual two-wicked lamp (see Camphene to Kerosene Lamps).

Forest Oil Company Logo

After experimenting with injecting water into some wells to increase production from others, Forest Dorn partnered with his father Clayton in 1916 to establish Forest Oil, an oilfield service company in Pennsylvania’s giant Bradford oilfield.

The company in February 1824 adopted the two-wicked oilfield derrick lamp as part of its logo, which included a keystone shape inside the lantern to symbolize the state of Pennsylvania — where the first commercial U.S. oil well was drilled in Titusville in 1859.

Forest Oil Company developed an extremely efficient technique for “secondary recovery” of trapped petroleum reservoirs. The waterflooding proved revolutionary for improving oilfield production nationwide. The technological leap began at America’s first giant oilfield, discovered in 1871 in Bradford, about 70 miles east of Titusville.

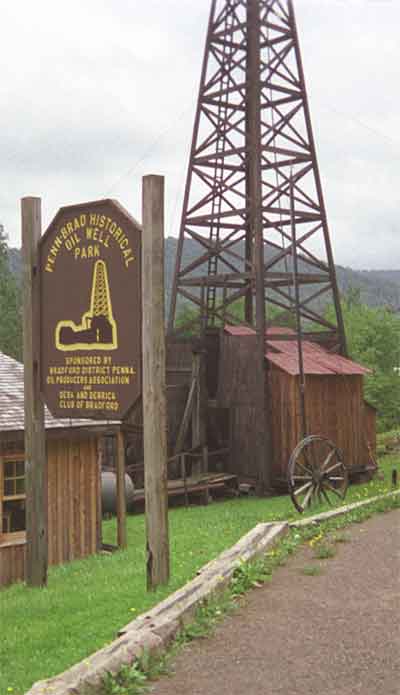

An oil museum near Bradford, Pennsylvania, educates visitors using a replica of an 1880s standard cable-tool derrick. Photo by Bruce Wells.

By 1916, oil production in the Bradford field had declined to just under 40 barrels a day. The reserve was considered by many to be dry — until Forest Dorn had applied his water-flooding technique to initiate secondary recovery of oil. Forest Oil became widely recognized as a leader in secondary oil recovery systems.

Water-flooding boosted oilfield production and arrived as demand for gasoline was growing (see Cantankerous Combustion – First U.S. Auto Show). The rapidly growing science of petroleum geology also led to more “secondary recovery” technologies.

Enhanced recovery would be applied throughout the petroleum industry, extending individual well production by 10 years — especially benefitting the already considerable production from the largest oilfield in the lower 48 states, the East Texas oilfield, discovered in 1930.

Oil Museums

The history of America’s “first billion-dollar oilfield” is on exhibit at the Penn-Brad Historical Oil Park and Museum near Bradford, Pennsylvania — where a modern natural gas shale boom has renewed the historic oil patch economy.

Located in Custer City, three miles south of Bradford (home of Zippo lighters), the museum (maintained by many dedicated volunteers) “preserves the philosophy, the spirit, and the accomplishments of an oil country community.”

One attraction of the Penn-Brad museum is its 72-foot standard cable-tool derrick and engine house, replicas of 1880s technology that helped Bradford once produce 74 percent of all U.S. oil. It’s another noteworthy stop among other excellent Pennsylvania oil museums a few hours west of Bradford at the Drake Well Museum in Titusville.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Early Days of Oil: A Pictorial History of the Beginnings of the Industry in Pennsylvania (2000); Images of America: Around Bradford

(1997); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Yellow Dog – Oilfield Lantern.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/yellow-dog-oil-field-lantern. Last Updated: April 22, 2025. Original Published Date: September 1, 2008.