by Bruce Wells | Dec 27, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

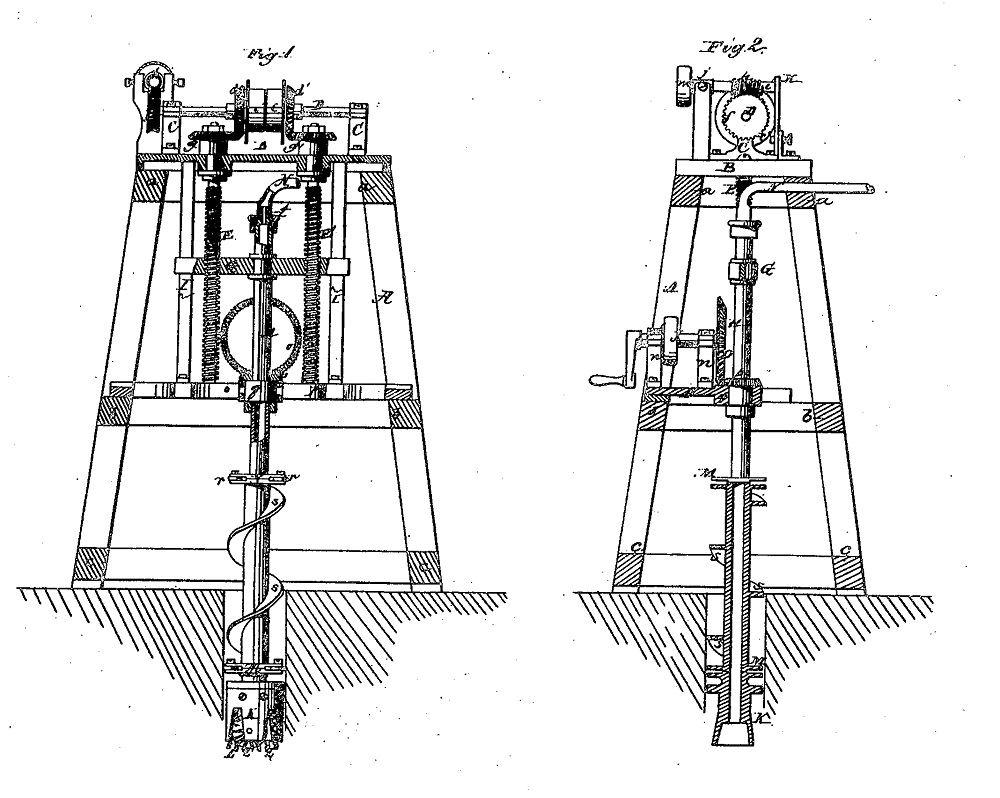

Early patent for a hollow “drill-rod” and roller bit for “making holes in hard rock.”

An “Improvement in Rock Drills” patent issued to a New Yorker after the Civil War included the basic elements of the modern petroleum industry’s rotary rig.

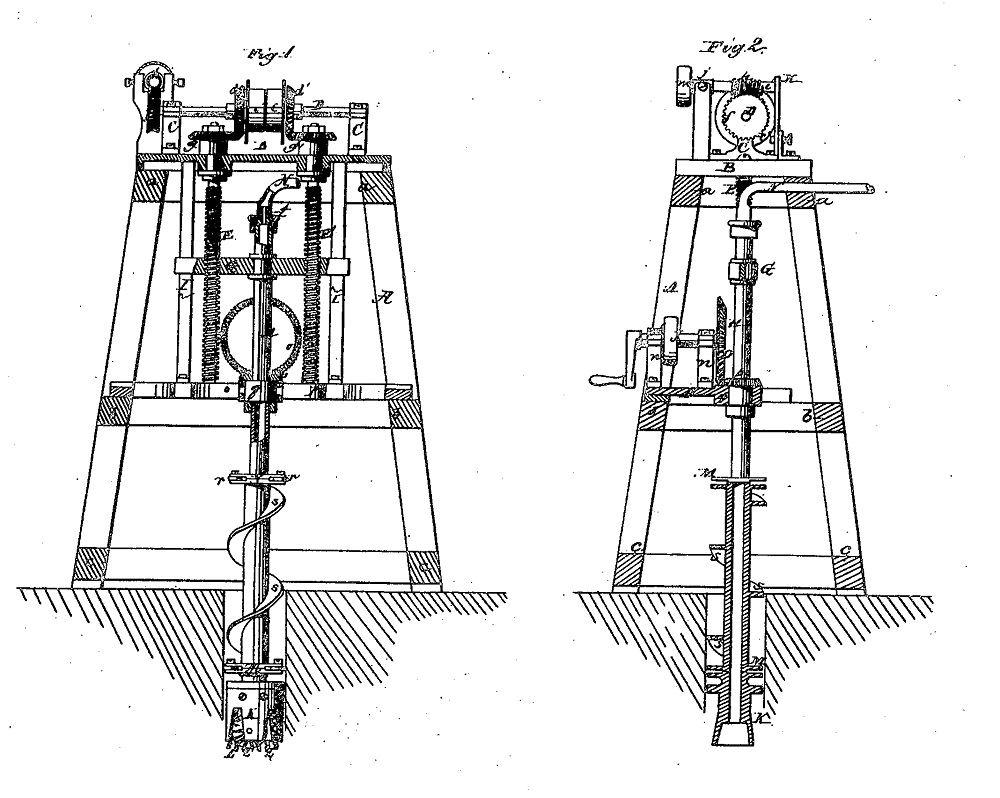

On January 2, 1866, Peter Sweeney of New York City was granted U.S. patent No. 51,902 for a drilling system with many new technologies. His rotary rig design, which improved upon an 1844 British patent by Robert Beart, applied the rotary drilling method’s “peculiar construction particularly adapted for boring deep wells.”

Peter Sweeney’s 1866 “Stone Drill” patent included a roller bit using a “rapid rotary motion” that would evolve into modern rotary drilling technologies.

Sweeney’s design provided for a roller bit with replaceable cutting wheels such that “by giving the head a rapid rotary motion the wheels cut into the ground or rock and a clean hole is produced.”

Deeper Drilling

In another Sweeny innovation, the “drill-rod” was hollow and connected with a hose through which “a current of steam or water can be introduced in such a manner that the discharge of the dirt and dust from the bottom of the hole is facilitated.”

Better than commonly used steam-powered cable-tool technology, which used a heavy rope to lift and drop iron chisel-like bits, Sweeney claimed his drilling apparatus could be used with great advantage for “making holes in hard rock in a horizontal, oblique, or vertical direction.”

Drilling operations could be continued without interruption, Sweeny explained in his patent application, “with the exception of the time required for adding new sections to the drill rod as the depth of the hole increases. The dirt is discharged during the operation of boring and a clean hole is obtained into which the tubing can be introduced without difficulty.”

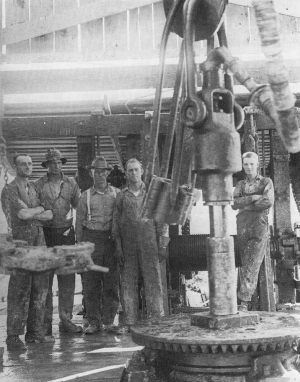

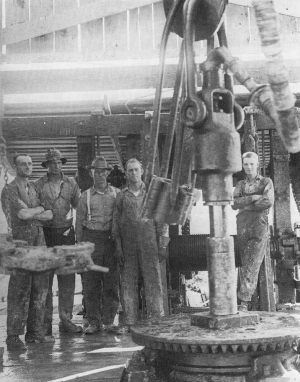

A 1917 rotary rig in the Coalinga, California, oilfield, where R.C. “Carl” Baker invented many advanced drilling technologies. Photo courtesy of the Joaquin Valley Geology Organization.

Foreseeing the offshore exploration industry, Sweeney’s patent concluded with a note that “the apparatus can also be used with advantage for submarine operations.”

With the U.S. oil industry’s rapid growth after the first commercial well in 1859, drilling contractors improved upon Sweeney’s 1866 innovations. Cable-tool methods also improved as wells got deeper.

In 1891, Andrew J. Ross patented (No. US459309A) a method “to provide simple and efficient means for rotating the well-tubing, to provide a removable drilling-bit adapted to be rotated by the said well-tubing, which bit when the well is bored may be removed.

Among later drilling advancements was a device fitted to the rig’s rotary table that clamped around the drill pipe and turned. As this “kelly bushing” rotated, the pipe rotated, and with it the bit downhole. The torque of the rotary table was transmitted to the drill stem.

Thirty-five years after Sweeney’s patent, rotary drilling revolutionized the petroleum industry after a 1901 oil discovery by Capt. Anthony Lucas at Spindletop Hill in Texas. Less than a decade later, Howard Hughes Sr. tested a rotary bit with twin-cones that could drill through hard rock, helping to find previously unreachable oil and natural gas reserves.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2007); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Sweeney’s 1866 Rotary Rig.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/1866-patent-rotary-rig. Last Updated: December 27, 2025. Original Published Date: January 2, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 26, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Giant Oklahoma rigs drilled to record depths in the 1970s.

The Anadarko Basin, extending more than 50,000 square miles across west-central Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle, includes some of the most prolific U.S. natural gas reserves — and a 1974 drilling record.

Beginning in the late 1950s, when technological advances allowed it, Anadarko Basin wells in Oklahoma began to be drilled more than two miles deep in search of natural gas. Dangerous, highly pressurized formations required state-of-the-art blowout preventers (see Ending Oil Gushers — BOP). (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 11, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

“Small cannons throwing a three-inch solid shot are kept at various stations throughout the region…”

Early petroleum technologies included cannons for fighting oil tank storage fires, especially in the Great Plains, where lightning strikes ignited derricks, engine houses, and tanks. Shooting a cannonball into the base of a burning storage tank allowed oil to drain into a holding pit or ditch, putting out the fire.

“Oil fires, like battles, are fought by artillery,” proclaimed the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in December 1884. Oilfield conflagrations challenged America’s petroleum industry since the first commercial well in 1859 (see First Oil Well Fire). An MIT student offered a recent, first-person account.

Especially in Midwest oilfields, lightning strikes could ignite derricks, engine houses, and rows of storage tanks. Photo courtesy Butler County History Center & Kansas Oil Museum.

“Lightning had struck the derrick, followed pipe connections into a nearby tank and ignited natural gas, which rises from freshly produced oil. Immediately following this blinding flash, the black smoke began to roll out,” the writer noted in The Tech, a student newspaper established in 1881.

The MIT article, “A Thunder Storm in the Oil Country,” described what happened next:

“Without stopping to watch the burning tank-house and derrick, we followed the oil to see where it would go. By some mischance the mouth of the ravine had been blocked up and the stream turned abruptly and spread out over the alluvial plain,” reported the article.

Oilfield operators used muzzle-loading cannons to fire solid shot at the base of burning oil tanks, draining the oil into ditches to extinguish the blaze.

“Here, on a large smooth farm, were six iron storage tanks, about 80 feet in diameter and 25 feet high, each holding 30,000 barrels of oil,” it added, noting the burning oil “spread with fearful rapidity over the level surface” before reaching an oil storage tank.

“Suddenly, with a loud explosion, the heavy plank and iron cover of the tank were thrown into the air, and thick smoke rolled out,” the writer observed.

“Already the news of the fire had been telegraphed to the central office, and all its available men and teams in the neighborhood ordered to the scene,” he added. “The tanks, now heated on the outside as well as inside, foamed and bubbled like an enormous retort, every ejection only serving to increase the heat.”

Technological innovations in Oklahoma oilfields helped improve petroleum production worldwide. The oilfield artillery exhibit at the Oklahoma Oil Museum in Seminole educated visitors until the museum closed in 2019. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The area of the fire rapidly extended to two more tanks: “These tanks, surrounded by fire, in turn boiled and foamed, and the heat, even at a distance, was so intense that the workmen could not approach near enough to dig ditches between the remaining tanks and the fire.”

Noting the arrival of “the long looked for cannon,” the reporter noted, adding, “Since the great destruction is caused by the oil becoming overheated, foaming and being projected to a distance, it is usually desirable to let it out of the tank to burn on the ground in thin layers; so small cannons throwing a three-inch solid shot are kept at various stations throughout the region for this purpose.”

The wheeled cannon was placed in position and “aimed at points below the supposed level of the oil and fired,” explained the witness. “The marksmanship at first was not very good, and as many shots glanced off the iron plates as penetrated, but after a while nearly every report was followed by an outburst.”

The oil in three storage tanks was slowly drawn down by this means, “and did not again foam over the top, and the supply to the river being thus cut off, the fire then soon died away.”

Mobil Oil in 1969 donated to Corsicana, Texas, a cannon that once stood at the Magnolia Petroleum tank farm “to shoot a hole in the bottom of the Cyprus tanks if lightning struck.”

In the end, “it was not till the sixth day from that on which we saw the first tank ignited that the columns of flame and smoke disappeared,” the 1884 MIT article concluded. “During this time 180,000 barrels of crude oil had been consumed, besides the six tanks, costing $10,000 each, destroyed.”

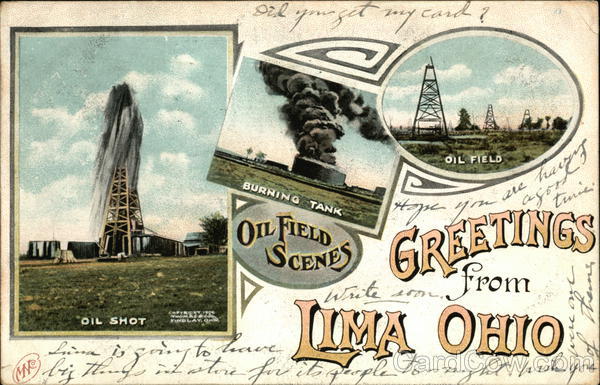

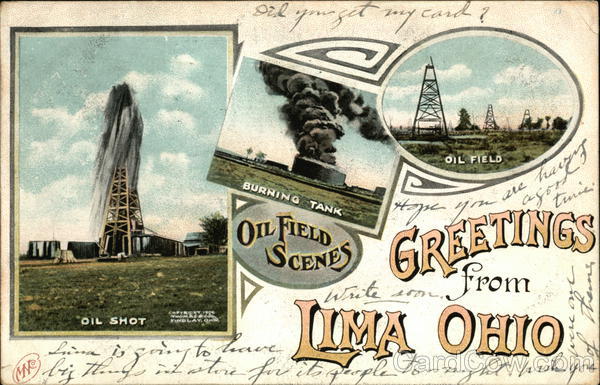

Postcards promoted a community’s petroleum prosperity with images of gushers and burning oil tanks. The Lima oilfield was discovered in 1885. Circa 1910 postcard published by Robbins Bros., Boston.

Visitors to Corsicana, Texas — where oil was discovered while drilling for water in 1894 (see First Texas Oil Boom) — can view an oilfield cannon donated to the city in 1969 by Mobil Oil. The marker notes:

“Fires were a major concern of oil fields. This cannon stood at the Magnolia Petroleum tank farm in Corsicana. It was used to shoot a hole in the bottom of the Cyprus tanks if lightning struck. The oil would drain into a pit around the tank to be pumped away. The cannon was donated by Mobil Oil Company in 1969.”

Another cannon can be found on exhibit in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, near the first Oklahoma oil well, drilled a decade before 1907 statehood. Exhibits at Discovery One Park include an 84-foot cable-tool derrick first erected in 1948 and replaced in 2008.

Still more oilfield artillery also can be found at the Kansas Oil Museum in Butler County. Another educates tourists in Ohio.

An oilfield cannon exhibit in Discovery One Park in Bartlesville, site of the first significant Oklahoma oilfield discovery of 1897. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Wood County Historical Center and Museum in Bowling Green displays its “unusual fire extinguisher” among its petroleum-artifact collection. The Buckeye Pipeline Company of Norwood donated the cannon, according to the museum’s director, Kelli King.

“The cannon, cast in North Baltimore (Ohio), was used in the 1920s in Cygnet before being moved to Northwood,” Kelli reported in 2005, adding that more local history can be found in the museum’s documentary “Ohio Crude” and in its exhibit, “Wood County in Motion.”

Museums in nearby Hancock County and Allen County also have petroleum collections from the Buckeye State’s oilfields.

Modern Oilfield Firefighting

When oilfield well control expert and firefighter Paul “Red” Adair died at age 89 in 2004, he left behind a famous “Hell Fighter” legacy. The son of a blacksmith, Adair was born in 1915 in Houston and served with a U.S. Army bomb disposal unit during World War II.

Adair began his career working for Myron M. Kinley, who patented a technology for using charges of high explosives to snuff out well fires. Kinley, whose father had been an oil well shooter in California in the early 1900s, also mentored Asger “Boots” Hansen and “Coots” Mathews of Boots & Coots International Well Control and other firefighters.

Famed oilfield firefighter Paul “Red” Adair of Houston, Texas, in 1964.

In 1959, Adair founded Red Adair Company in Houston and soon developed innovative techniques for “wild well” control. His company would put out more than 2,000 well fires and blowouts worldwide — onshore and offshore.

The Texas firefighter’s skills were tested in 1991 when Adair and his company extinguished 117 oil well fires set in Kuwait by Saddam Hussein’s retreating Iraqi army. Adair was joined by other pioneering well firefighting companies, including Cudd Well Control, founded by Bobby Joe Cudd in 1977.

Russian Anti-Tank Gun

Unable to control a 2020 oil well fire in Siberia, a Russian oil company called in the army. In May, a well operated by the Irkutsk Oil Company in Russia’s Irkutsk region ignited into a geyser of flame. When Irkutsk Oil Company firefighters were unable to extinguish the blaze, the Russian Defense Ministry flew a Rapira MT-12 anti-tank gun to the well site.

The Russian army’s 100-millimeter gun repeatedly fired at the flaming wellhead, “breaking it from the well and allowing crews to seal the well,” according to a June 8, 2020, article in Popular Mechanics.

In 1966, the Soviet Union used a nuclear device to extinguish a natural gas fire — as U.S. scientists experimented with nuclear fracturing of natural gas wells (see Project Gasbuggy tests Nuclear “Fracking”).

Learn more about the earliest oilfield fires and how the petroleum industry fought them with cannons, wind-making machines (including jet engines), and nuclear bombs in Oilfield Firefighting Technologies.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Oilfield Artillery fights Fires.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/oilfield-artillery-fights-fires. Last Updated: December 11, 2025. Original Published Date: September 1, 2005.

by Bruce Wells | Dec 6, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

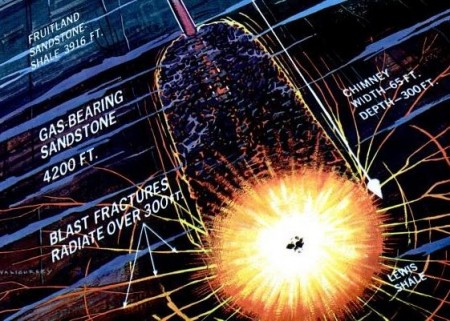

Government scientists experimented with atomic blasts to fracture natural gas wells.

Project Gasbuggy was the first in a series of Atomic Energy Commission downhole nuclear detonations to release natural gas trapped in shale. This was “fracking” late 1960s style.

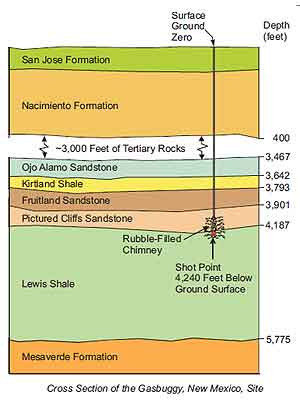

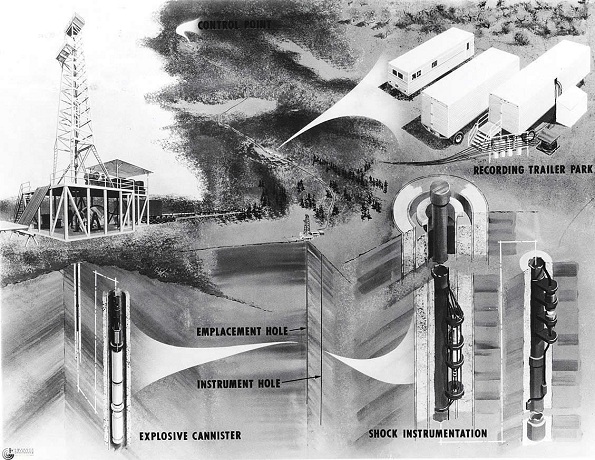

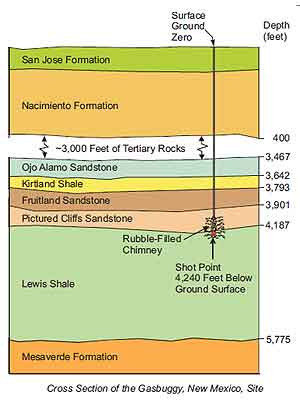

In December 1967, government scientists — exploring the peacetime use of controlled atomic explosions — detonated Gasbuggy, a 29-kiloton nuclear device they had lowered into an experimental well in rural New Mexico. The Hiroshima bomb of 1945 was about 15 kilotons.

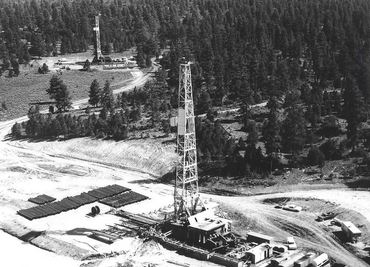

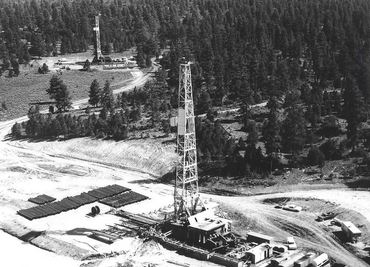

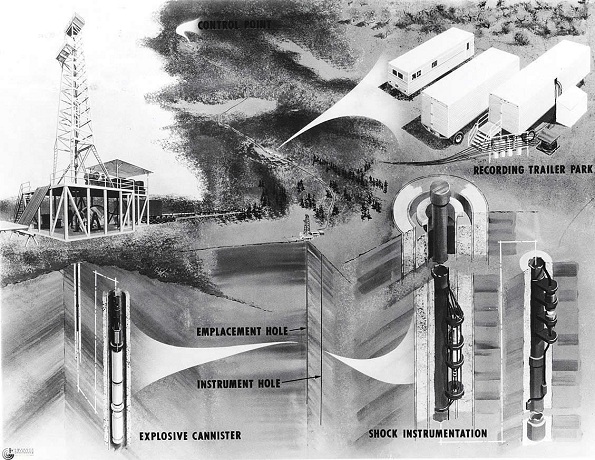

Scientists prepare to lower a 13-foot by 18-inch diameter nuclear device into a New Mexico natural gas well in December 1967. The Project Gasbuggy 29-kiloton bomb will be detonated at a depth of 4,240 feet. Photo courtesy Los Alamos Lab.

The Project Gasbuggy team included experts from the Atomic Energy Commission, the U.S. Bureau of Mines, and El Paso Natural Gas Company. They sought a new, powerful method for fracturing petroleum-bearing formations.

Near three low-production natural gas wells, the team drilled to a depth of 4,240 feet — and lowered a 13-foot-long by 18-inch-wide nuclear device into the borehole.

Plowshare Program: Peaceful Nukes

The 1967 experimental explosion in New Mexico was part of a wider set of experiments known as Plowshare, a program established by the Atomic Energy Commission in 1957 to explore the constructive use of nuclear explosive devices.

“The reasoning was that the relatively inexpensive energy available from nuclear explosions could prove useful for a wide variety of peaceful purposes,” noted a report later prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy.

From 1961 to 1973, researchers carried out dozens of separate experiments under the Plowshare program — setting off a total of 29 nuclear detonations. Most of the experiments focused on creating craters and canals. Among other goals, federal officials hoped the Panama Canal could be inexpensively widened.

“In the end, although less dramatic than nuclear excavation, the most promising use for nuclear explosions proved to be for stimulation of natural gas production,” explained the September 2011 government report.

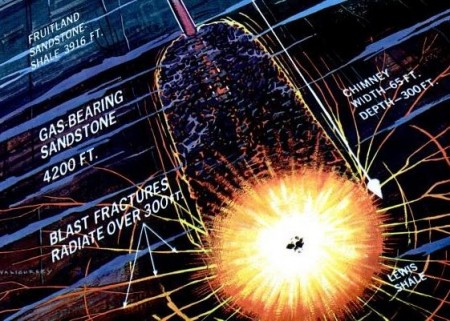

Detonated 60 miles from Farmington in 1967, the first nuclear detonation created a “Rubble Filled Chimney,” producing 295 million cubic feet of natural gas — and deadly Tritium radiation.

Tests, mostly conducted in Nevada, also took place in the petroleum fields of New Mexico and Colorado. Project Gasbuggy was the first of three nuclear fracturing experiments that focused on stimulating natural gas production. Two later tests took place in Colorado.

Atomic Energy Commission scientists worked with experts from the Astral Oil Company of Houston, with engineering support from CER Geonuclear Corporation of Las Vegas. The experimental wells, which required custom drill bits to meet the hole diameter and narrow hole deviation requirements, were drilled by Denver-based Signal Drilling Company or its affiliate, Superior Drilling Company.

Projects Rulison and Rio Blanco

In 1969, Project Rulison, the second of the three nuclear well stimulation projects, blasted a natural gas well near Rulison, Colorado. Scientists detonated a 43-kiloton nuclear device almost 8,500 feet underground to produce commercially viable amounts of natural gas.

In 1973, another fracturing experiment at Rio Blanco, northwest of Rifle, Colorado, was designed to increase natural gas production from low-permeability sandstone.

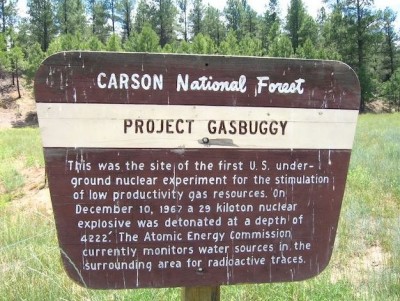

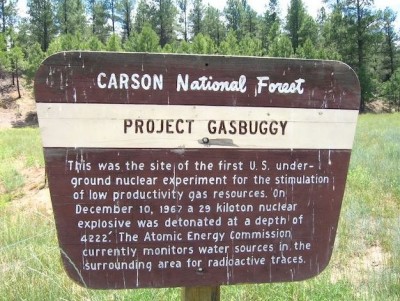

Gasbuggy: “Site of the first United States underground nuclear experiment for the stimulation of low-productivity gas reservoirs.” Photo courtesy DOE.

The May 1973 Rio Blanco test consisted of the nearly simultaneous detonation of three 33-kiloton devices in a single well, according to the Office of Environmental Management. The explosions occurred at depths of 5,838, 6,230, and 6,689 feet below ground level. It would prove to be the last experiment of the Plowshare program.

Although a 50-kiloton nuclear explosion to fracture deep oil shale deposits — Project Bronco — was proposed, it never took place. Growing knowledge (and concern) about radioactivity ended these tests for the peaceful use of nuclear explosions. The Plowshare program was canceled in 1975.

Decades later, after an examination of all the nuclear test projects, the U.S. Department of Energy reported that by 1974, about 82 million dollars had been invested in the nuclear gas stimulation technology program (i.e., nuclear tests Gasbuggy, Rulison, and Rio Blanco).

The September 2011 DOE report estimated that even after 25 years of gas production of all the natural gas deemed recoverable, only 15 to 40 percent of the investment could be recovered. At the same time, alternative, non-nuclear technologies were being developed, such as hydrofracturing.

DOE concluded that consequently, under the pressure of economic and environmental concerns, the Plowshare Program was discontinued at the end of FY 1975.

Project Gasbuggy: Nuclear Fracking

“There was no mushroom cloud, but on December 10, 1967, a nuclear bomb exploded less than 60 miles from Farmington,” explained historian Wade Nelson in an article written three decades later, “Nuclear explosion shook Farmington.”

Government scientists believed a nuclear device would provide “a bigger bang for the buck than nitroglycerin” for fracturing dense shales and releasing natural gas. Illustration courtesy Los Alamos Lab.

The 4,042-foot-deep detonation created a molten glass-lined cavern about 160 feet in diameter and 333 feet tall. It collapsed within seconds. Subsequent measurements indicated fractures extended more than 200 feet in all directions — and significantly increased natural gas production.

A September 1967 Popular Mechanics article described how nuclear explosives could improve previous fracturing technologies, including gunpowder, dynamite, TNT — and fractures “made by forcing down liquids at high pressure.”

Hydraulic fracturing technologies pump a mixture of fluid and sand down a well at extremely high pressure to stimulate production of oil and natural gas wells.

The first commercial application of hydraulic fracturing took place in March 1949 near Duncan, Oklahoma, following experiments in a Kansas natural gas field. Increasing oil production by fracturing geologic formations had begun about a century earlier (see Shooters – A “Fracking” History).

A 1967 illustration in Popular Mechanics magazine showed how a nuclear explosive would improve earlier technologies by creating bigger fractures and a “huge cavity that will serve as a reservoir for the natural gas.”

Scientists predicted that nuclear explosives would create more and bigger fractures “and hollow out a huge cavity that will serve as a reservoir for the natural gas” released from the fractures.

“Geologists had discovered years before that setting off explosives at the bottom of a well would shatter the surrounding rock and could stimulate the flow of oil and gas,” Nelson explained. “It was believed a nuclear device would simply provide a bigger bang for the buck than nitroglycerin, up to 3,500 quarts of which would be used in a single shot.”

The first 1967 underground detonation test was part of a broader federal program begun in the late 1950s to explore the peaceful uses of nuclear explosions.

“Today, all that remains at the site is a plaque warning against excavation and perhaps a trace of tritium in your milk,” Nelson added in his 1999 article. He quoted James Holcomb, the site foreman for El Paso Natural Gas, who saw a pair of white vans that delivered pieces of the disassembled nuclear bomb.

“They put the pieces inside this lead box, this big lead box…I (had) shot a lot of wells with nitroglycerin and I thought, ‘That’s not going to do anything,” reported Holcomb. A series of three production tests, each lasting 30 days, was completed during the first half of 1969. Government records indicated the Gasbuggy well produced 295 million cubic feet of natural gas.

“Nuclear Energy: Good Start for Gasbuggy,” proclaimed the December 22, 1967, TIME magazine. The Department of Energy, which had hoped for much higher production, determined that Tritium radiation contaminated the gas. It flared — burned off — the gas during production tests that lasted until 1973. Tritium is a naturally occurring radioactive form of hydrogen.

A 2012 Nuclear Regulatory Commission report noted, “Tritium emits a weak form of radiation, a low-energy beta particle similar to an electron. The tritium radiation does not travel very far in air and cannot penetrate the skin.”

A plaque marks the site of Project Gasbuggy in the Carson National Forest, 90 miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico.

According to Nelson, radioactive contamination from the flaring “was minuscule compared to the fallout produced by atmospheric weapons tests in the early 1960s.” From the well site, Holcomb called the test a success. “The well produced more gas in the year after the shot than it had in all of the seven years prior,” he said.

In 1972, the Environmental Protection Agency began monitoring groundwater and surface water near the Gasbuggy site. In 2008, the Energy Department’s Office of Legacy Management assumed responsibility for long-term surveillance and maintenance at the Gasbuggy site.

DOE took responsibility for the hydrological monitoring program, and began monitoring natural gas and water produced with natural gas wells near the site. With no Gasbuggy-related contaminants identified at the sampled gas wells by 2015, DOE discontinued the groundwater and surface water monitoring program.

A DOE marker placed at the Gasbuggy site in November 1978 reads:

Site of the first United States underground nuclear experiment for the stimulation of low-productivity gas reservoirs. A 29 kiloton nuclear explosive was detonated at a depth of 4227 feet below this surface location on December 10, 1967. No excavation, drilling, and/or removal of materials to a true vertical depth of 1500 feet is permitted within a radius of 100 feet of this surface location. Nor any similar excavation, drilling, and/or removal of subsurface materials between the true vertical depth of 1500 feet to 4500 feet is permitted within a 600 foot radius of T 29 n. R 4 w. New Mexico principal meridian, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico without U.S. Government permission.

USSR’s Project NEVA

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) responded with its own more extensive program in 1965, according to a declassified 1981 Central Intelligence Agency report.

The CIA assessment, “The Soviet Program for Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Explosions,” reported that by the mid-1970s, the Soviets had detonated nine nuclear devices in seven Siberian fields to increase natural gas production as part of Project NEVA – Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy.

The USSR atomic tests delivered essentially the same conclusion as did America’s Project Gasbuggy – no commercially feasible petroleum production — and not popular with the public because of environmental concerns. The USSR abandoned Project NEVA experiments in 1989, more than a decade after the end of America’s Plowshare program.

Parker Drilling Rig No. 114

In 1969, Parker Drilling Company signed a contract with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to drill a series of holes up to 120 inches in diameter and 6,500 feet in depth in Alaska and Nevada for additional nuclear tests. Parker Drilling’s Rig No. 114 was one of three special rigs built to drill the wells.

Parker Drilling Rig No. 114 was among those used to drill wells for nuclear detonations and later modified to drill conventional, very deep wells. Since 1991, the 17-story rig has welcomed visitors to Elk City, Oklahoma, next to the shuttered Anadarko Museum of Natural History. Photo by Bruce Wells.

Founded in Tulsa in 1934 by Gifford C. Parker, by the 1960s Parker Drilling had set numerous world records for deep and extended-reach drilling.

According to the Baker Library at the Harvard Business School, the company “created its own niche by developing new deep-drilling technology that has since become the industry standard.”

Following completion of the nuclear-test wells, Parker Drilling modified Rig No. 114 and its two sister rigs to drill conventional wells at record-breaking depths.

After retiring Rig No. 114 from oilfields, Parker Drilling in 1991 loaned it to Elk City, Oklahoma, as an energy education exhibit next to the Anadarko Museum of Natural History, which later closed. The 17-story rig has remained there to welcome Route 66 and I-40 travelers.

Learn about drilling miles deep in Anadarko Basin in Depth.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Atoms for Peace and War 1953-1961 (2017); Project Plowshare: The Peaceful Use of Nuclear Explosives in Cold War America

(2017); Project Plowshare: The Peaceful Use of Nuclear Explosives in Cold War America (2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2012). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Project Gasbuggy tests Nuclear “Fracking”.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/project-gasbuggy. Last Updated: December 7, 2025. Original Published Date: December 10, 2013.

by Bruce Wells | Nov 29, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Scientists experiment with reflection seismography in 1921.

Exploring seismic waves is all about the vital earth science technology — reflection seismography — which revolutionized petroleum exploration in the 1920s. Seismic waves have led to oilfield discoveries worldwide and billions of barrels of oil.

(more…)

by Bruce Wells | Nov 19, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

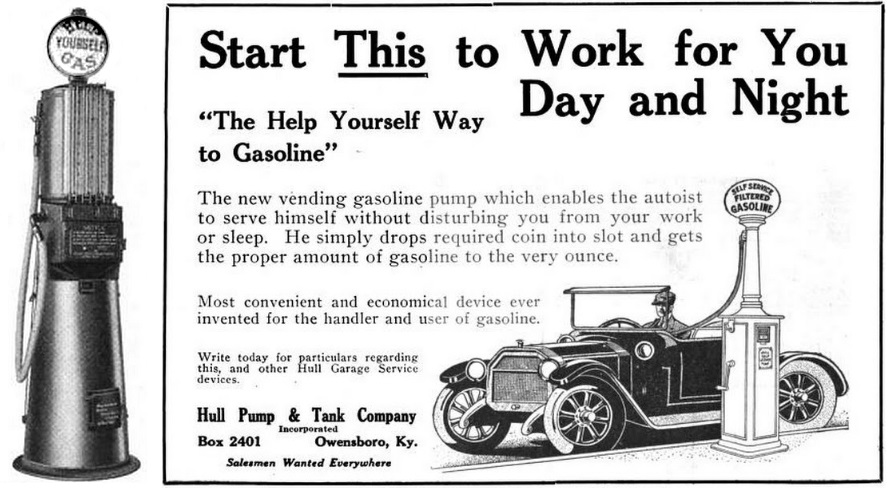

“Drop the coin in the slot…Mr. Robot delivers the correct amount of gasoline.”

Almost as soon as gasoline service stations appeared, inventors began experimenting with ways to make user-friendly pumps for consumers. The revenue possibilities of 24-hour self-service gasoline pumps prompted a number of innovators to develop coin-operated systems in the early 20th century.

Self-measuring pumps once used to dispense kerosene were adapted for gasoline (see Wayne’s Self-Measuring Pump), even as inventors sought ways to automate payment at the pump.

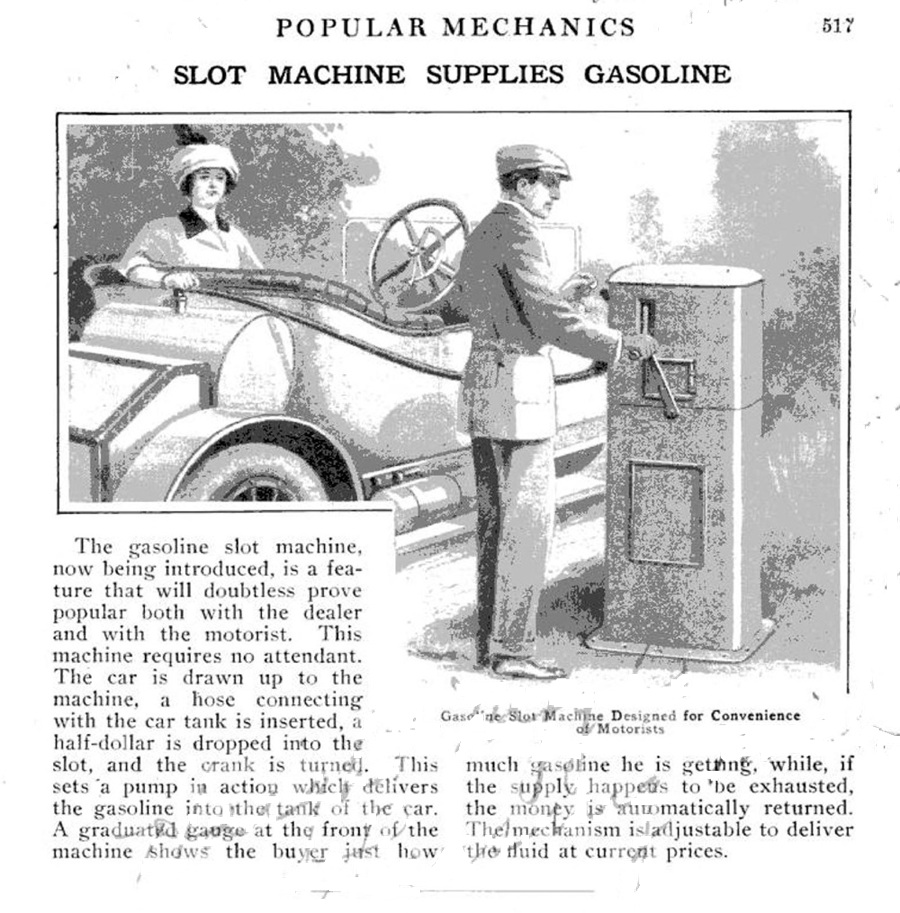

Scientific American and Popular Mechanics featured some of the early designs for coin-operated gasoline pumps, noting that manufacturers took their cue from “the fortunes that have resulted from the harvest of pennies dropped into chewing gum slot machines.”

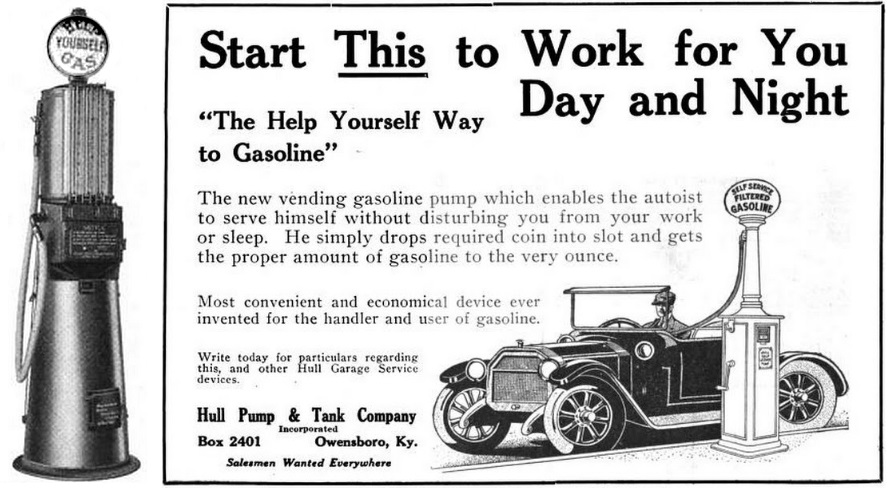

Trade magazines like Garage Dealer and Motor Age featured advertisements for coin-operated gas pump technologies of the 1920s.

But a coin-operated pump had risks, noted editors at Scientific American: “It is evident that a vending machine liable to hold fifty or a hundred half-dollars would be a magnet for thieves.”

The Anthony Liquid Vending Machine Company designed its “Anthony Automatic Salesman,” which the company marketed to garage owners, promising a savings of $5 in overhead costs for every dollar invested in the automatic, coin-operated pumps.

In Minnesota, William H. Fruen received the first U.S. patent for a coin-operated liquid dispensing apparatus in 1884. The inventor from Minneapolis designed an innovative “Automatic Liquid-Drawing Device,” according to Canadian historian K.J. Zeoli.

Starky Coin-Operated Pumps

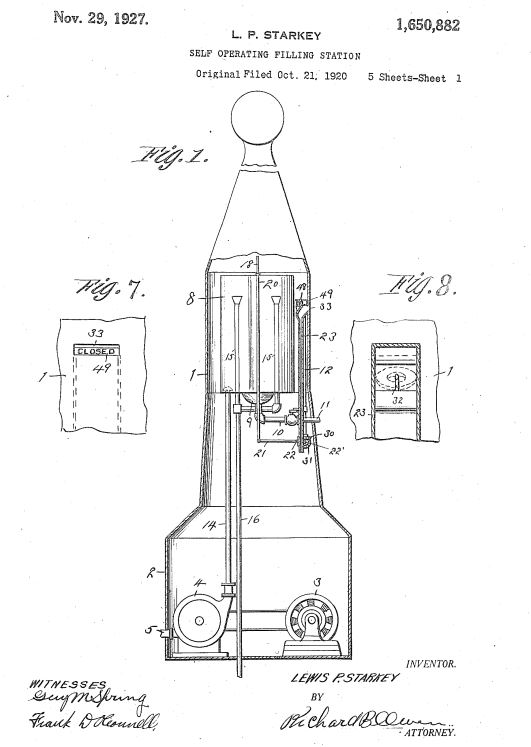

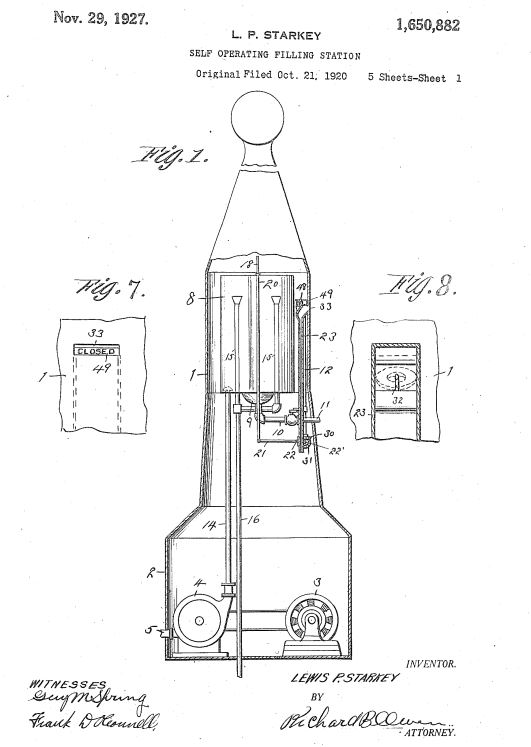

One of the better-known coin-operated pump manufacturers originated with the Starkey Oil and Gas Company of Fort Collins, Colorado. Lewis P. Starkey, who first filed an application in October 1920, received his U.S. patent on November 29, 1927 (patent no. 1650882), which used electricity instead of a manual cranking system.

Patent drawing of “Self-Operating Filling Station,” the coin-operated gasoline pump invented by Lewis Starkey of Fort Collins, Colorado.

According to Zeoli, the L.P. Starkey Pump Company, which was later sold to Gas-O-Mat Inc. of Denver, produced two models of coin-operated pumps.

“Starkey and his wife ran a service station in Fort Collins. Starkey was constantly being awakened during the night by tourists who wanted gasoline. His wife actually came up with the idea of making a gas pump that would dispense gas without Starkey having to get out of bed and service the tourist. This gave Starkey the idea for the coi-operated pump.”

“Unfortunately, Starkey allowed his patent to expire on one of the key components in his pumps,” Zeoli reported. The component, a “silent mercury switch” that prevented electrical circuit sparks, “went on to be used by thousands in the construction business.”

Although coin-operated pumps at gas service stations would prove impractical, there were notable attempts in the early 20th century, according to Zeoli.

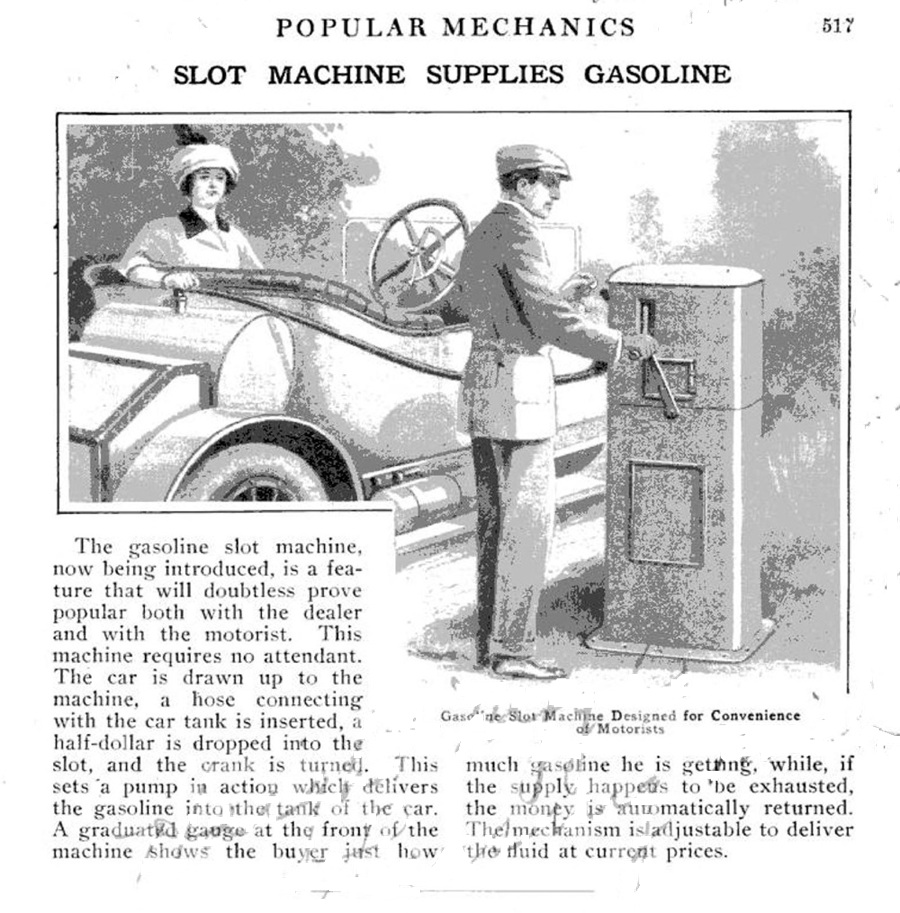

With the price of gas around 22 cents per gallon, the October 18, 1913, issue of Popular Mechanics featured a hand-cranked gasoline “slot machine.”

“This machine requires no attendant,” reported Popular Mechanics in 1913. Motorists could simply insert a half-dollar coin into a slot and turn a crank to pump gas.

In Popular Mechanics, the automatic pump was “touted as one of the first consumer friendly slot gas machines of the era,” Zeoli explained in a 2023 post on his Vintage Gas Pump & Oil History.

“The pump was so advanced, if a customer dropped a coin into an empty pump by mistake, the pump would return the coin after the first crank of the pump,” added Zeoli, a longtime collector and vintage pump expert.

Meanwhile, gasoline filling stations with uniformed attendants continued to expand nationwide following Gulf Oil’s example in Pittsburgh (see First Gas Pump and Service Station). Starkey Pump Company and a few other rare gas-pump-slot-machines examples survive in museums.

End of Gas-O-Mats

Gasoline dispensing automation seemed like a good idea, simply lacking the technology to make it work. Attempts continued as commercial names like Beacon, Gas-O-Mat, and others disappeared in a flurry of patents that could not overcome challenges of coin-operated pumps.

“You can sell gasoline 24 hours a day and 365 days a year, without effort on your part,” one company proclaimed, adding that paying was a simple process for consumers. “Drop the coin in the slot — a quarter, half-dollar, or a silver dollar, and Mr. Robot delivers the correct amount of gasoline.”

By 1915, an article in National Petroleum News reported a key drawback of unattended, coin-operated pumps: “One gasoline vending outfit tried out recently in a middle western city returned about $2 in real currency and $37 in lead slugs, buttons, and counterfeit coins for its first 500 gallons of gasoline.”

Nonetheless, as a system for numbered highways was established, and U.S. 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles was approved in 1926 (learn more in America On the Move), some coin-operated machines survived into the 1930s.

__________________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Coin Operated Gas Pumps.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/coin-operated-gasoline-pumps. Last Updated: November 21, 2025. Original Published Date: July 11, 2018.

(2007); The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (1991); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.