by Bruce Wells | Mar 3, 2026 | Petroleum Products

Camphene and popular but risky burning fluid are replaced by a brighter, less volatile lamp fuel.

In the early 19th century, lamp designs burned many different fuels, including rapeseed oil, lard, and whale oil rendered from whale blubber (and the more expensive spermaceti from the heads of sperm whales), but most Americans could only afford light emitted by animal-fat tallow candles.

By 1850, the U.S. Patent Office recorded almost 250 different patents for all manner of lamps, wicks, burners, and fuels to meet growing consumer demand for illumination. At the time, most Americans lived in almost complete darkness when the sun went down. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Feb 18, 2026 | Petroleum Products

A Revolutionary DuPont lab product first used commercially in 1938 for toothbrush bristles.

The world’s first synthetic fiber was the petroleum product “Nylon 6,” discovered in 1935 by a DuPont chemist who produced the polymer from chemicals found in oil.

DuPont Corporation foresaw the future of “strong as steel” artificial fibers. The chemical conglomerate had been founded in 1802 as a Wilmington, Delaware, manufacturer of gunpowder. The company would become a global giant after its scientists created durable and versatile products like nylon, rayon, and lucite.

“Women show off their nylon pantyhose to a newspaper photographer, circa 1942,” noted Jennifer S. Li in “The Story of Nylon – From a Depressed Scientist to Essential Swimwear.” Photo by R. Dale Rooks.

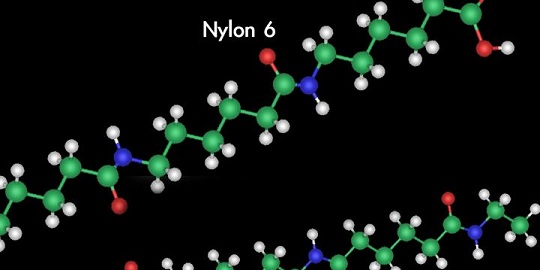

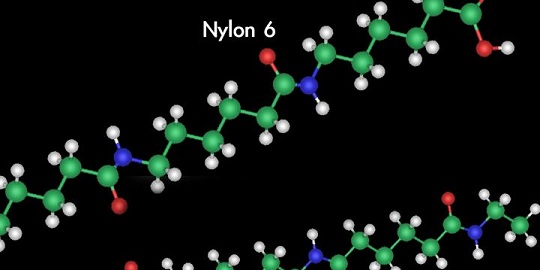

The world’s first synthetic fiber — nylon — was discovered on February 28, 1935, by a former Harvard professor working at a DuPont research laboratory. Called Nylon 6 by scientists, the revolutionary carbon-based product came from chemicals found in petroleum.

Chemists named the fiber Nylon 6 because chains of adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine each contained six carbon atoms per molecule.

Professor Wallace Carothers had experimented with artificial materials for more than six years. He previously discovered neoprene rubber (commonly used in wetsuits) and made major contributions to understanding polymers — large molecules composed of long chains of repeating chemical structures.

Polymer Chains

Carothers, 32, created fibers when he combined the chemicals amine, hexamethylene diamine, and adipic acid. His experiments formed polymer chains using a process in which individual molecules joined together with water as a byproduct. But the fibers were weak.

A PBS series, A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries, in 1998 noted Carothers’ breakthrough came when he realized, “the water produced by the reaction was dropping back into the mixture and getting in the way of more polymers forming. He adjusted his equipment so that the water was distilled and removed from the system. It worked!”

DuPont named the petroleum product nylon — although chemists called it Nylon 6 because the adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine each contain six carbon atoms per molecule.

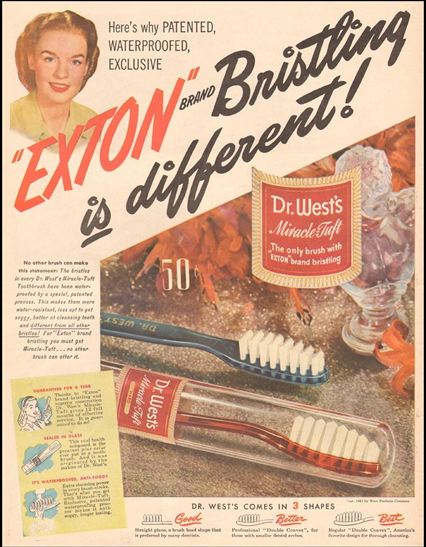

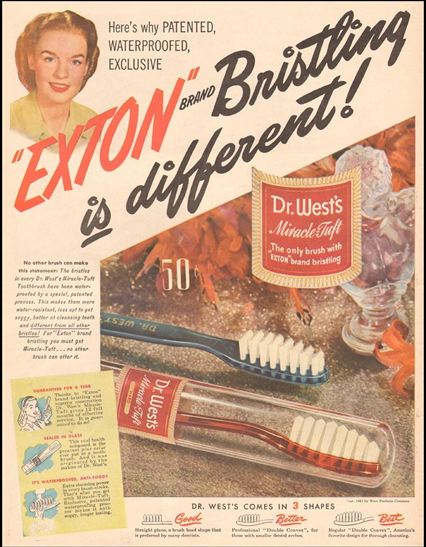

“Until now, all good toothbrushes were made with animal bristles,” noted a 1938 magazine ad.

Each man-made molecule consists of 100 or more repeating units of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms, strung in a chain. A single filament of nylon may have a million or more molecules, each taking some of the strain when the filament is stretched.

There’s disagreement about how the product name originated at DuPont.

“As to the word ‘nylon,’ it’s actually quite arbitrary. DuPont itself has stated that originally the name was intended to be No-Run (that’s run as in the sense of the compound chain of the substance unraveling), but at the time there was no real justification for the claim, so it needed to be changed,” noted Chris Nickson in a 2017 website post, Where Does the Name Nylon Originate?

Toothbrush Bristles

The first commercial use of this revolutionary petroleum product was for toothbrushes.

On February 24, 1938, the Weco Products Company of Chicago, Illinois, began selling its new “Dr. West’s Miracle-Tuft” — the earliest toothbrush to use synthetic DuPont nylon bristles.

First used for toothbrush bristles, nylon women’s stockings were widely promoted by DuPont in 1948.

Americans will soon brush their teeth with nylon — instead of hog bristles, declared an article in the New York Times. “Until now, all good toothbrushes were made with animal bristles,” explained a 1938 Weco Products advertisement in Life magazine.

“Today, Dr. West’s new Miracle-Tuft is a single exception,” the ad proclaimed. “It is made with EXTON, a unique bristle-like filament developed by the great DuPont laboratories and produced exclusively for Dr. West’s.”

Pricing its toothbrush at 50 cents, the Weco Products Company guaranteed “no bristle shedding.” Johnson & Johnson of New Brunswick, New Jersey, will introduce a competing nylon-bristle toothbrush in 1939.

Nylon Stockings

Although DuPont patented nylon in 1935, it was not officially announced to the public until October 27, 1938, in New York City.

A DuPont vice president unveiled the synthetic fiber — not to a scientific society or industry association — but to 3,000 Women’s Club members gathered at the site of the upcoming 1939 New York World’s Fair.

During WWII, nylon was used as a substitute for silk in parachutes.

“He spoke in a session entitled ‘We Enter the World of Tomorrow,’ which was keyed to the theme of the forthcoming fair, the World of Tomorrow,” explained DuPont historian David A. Hounshell in a 1988 book.

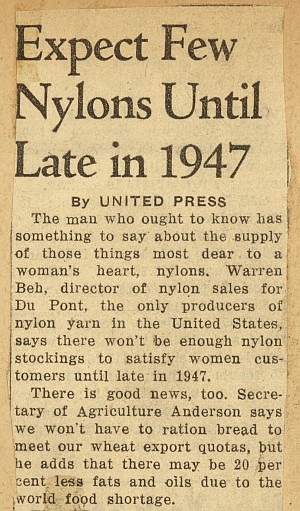

The petroleum product was an instant hit, especially as a replacement for silk in hosiery. DuPont built a full-scale nylon plant in Seaford, Delaware, and began commercial production in late 1939. The company purposefully did not register “nylon” as a trademark — choosing to allow the word to enter the American vocabulary as a synonym for “stockings.”

Women’s nylon stockings appeared for the first time at Gimbels Department Store on May 15, 1940. World War II would remove the polymer hosiery from stores since it was needed for parachutes and other vital supplies.

Nylon would become far and away the biggest money-maker in the history of DuPont. The powerful material from lab research led company executives to derive formulas for growth, according to Hounshell in The Nylon Drama.

“By putting more money into fundamental research, DuPont would discover and develop ‘new nylons,’ that is, new proprietary products sold to industrial customers and having the growth potential of nylon,” Hounshell explained in his 1988 book.

Carothers did not live to see the widespread application of his work — in consumer goods such as toothbrushes, fishing lines, luggage, and lingerie, or in special uses such as surgical thread, parachutes, or pipes — nor the powerful effect it had in launching a whole era of synthetics.

Devastated by the sudden death of his favorite sister in early 1937, Wallace Carothers committed suicide in April of that year. The DuPont Company would name its research facility after him.

The DuPont website notes that the invention of nylon changed the way people dressed worldwide and made the term ‘silk stocking’ obsolete (once an epithet directed at the wealthy elite). Nylon’s success encouraged DuPont and other companies to adopt long-term strategies for products developed from research.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History (2019); Enough for One Lifetime: Wallace Carothers, Inventor of Nylon (2005); The Nylon Drama (1988). Your Amazon purchases benefit the American Oil & Gas Historical Society; as an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please support AOGHS to help maintain this energy education website, a monthly email newsletter, This Week in Oil and Gas History News, and expand historical research. Contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2026 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Nylon, a Petroleum Polymer.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/petroleum-product-nylon-fiber. Last Updated: February 19, 2026. Original Published Date: February 23, 2014.

View Post

by Bruce Wells | Jan 28, 2026 | Petroleum Products

G.M. scientists discover the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead gasoline.

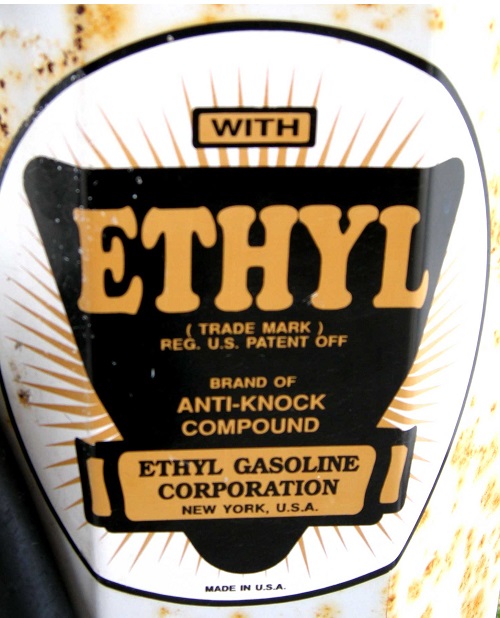

General Motors scientists in 1921 discovered the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead as an additive to gasoline. By 1923, many American motorists would be driving into service stations and saying, “Fill ‘er up with Ethyl.”

Early internal combustion engines frequently suffered from “knocking,” the out-of-sequence detonation of the gasoline-air mixture in a cylinder. The constant shock added to exhaust valve wear and frequently damaged engines.

Automobiles powered with gasoline had been the least popular models at the November 1900 first U.S. auto show in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

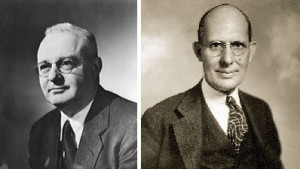

General Motors chemists Thomas Midgely Jr. and Charles F. Kettering tested many gasoline additives, including arsenic.

On December 9, 1921, after five years of lab work to find an additive to eliminate pre-ignition “knock” problems of gasoline, General Motors researchers Thomas Midgely Jr. and Charles Kettering discovered the anti-knock properties of tetraethyl lead.

Early experiments at GM examined the properties of knock suppressors such as bromine, iodine, and tin — comparing these to new additives such as arsenic, sulfur, silicon, and lead.

The world’s first anti-knock gasoline containing a tetra-ethyl lead compound went on sale at the Refiners Oil Company service station in Dayton, Ohio. A bolt-on “Ethylizer” can be seen running vertically alongside the visible reservoir. Photo courtesy Kettering/GMI Alumni Foundation.

When the two chemists synthesized tetraethyl lead and tried it in their one-cylinder laboratory engine, the knocking abruptly disappeared. Fuel economy also improved. Ethyl vastly improved gasoline performance.

“Ethylizers” debut in Dayton

Although being diluted to a ratio of one part per thousand, the lead additive yielded gasoline without the loud, power-robbing knock. With other automotive scientists watching, the first car tank filled with leaded gas took place on February 2, 1923, at the Refiners Oil Company service station in Dayton, Ohio.

In the beginning, GM provided Refiners Oil Company and other service stations special equipment, simple bolt-on adapters called “Ethylizers” to meter the proper proportion of the new additive.

“By the middle of this summer you will be able to purchase at approximately 30,000 filling stations in various parts of the country a fluid that will double the efficiency of your automobile, eliminate the troublesome motor knock, and give you 100 percent greater mileage,” Popular Science Monthly reported in 1924.

By the late 1970s, public health concerns resulted in the phase-out of tetraethyl lead in gasoline, except for aviation fuel.

Anti-knock gasoline containing a tetraethyl lead compound also proved vital for aviation engines during World War II, even as danger from the lead content increasingly became apparent.

Powering Victory in World War II

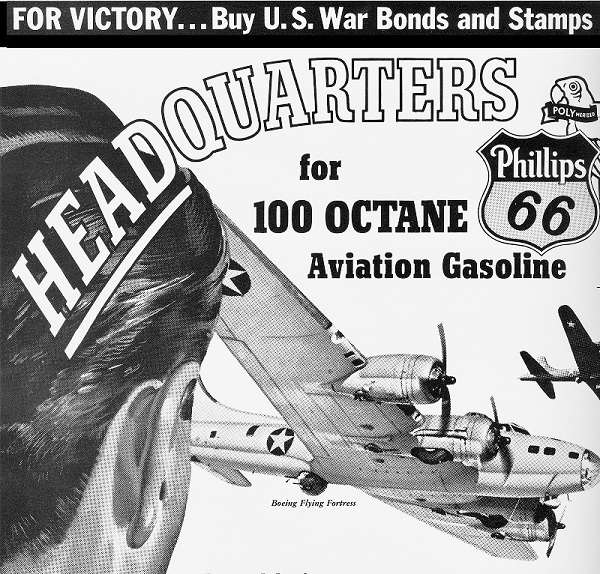

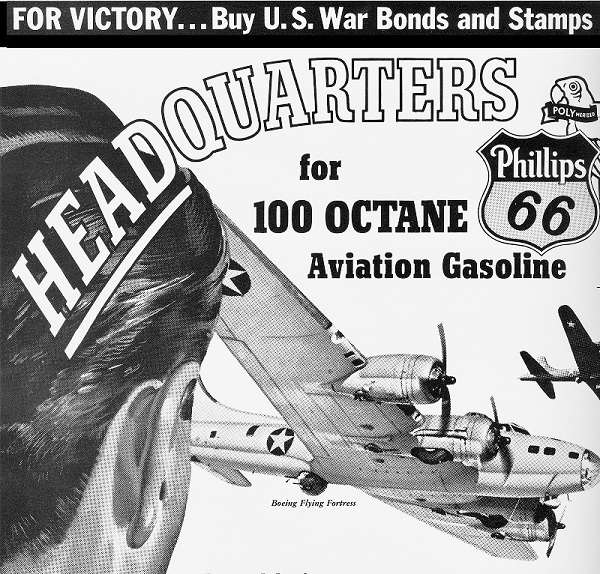

Aviation fuel technology was still in its infancy in the 1930s. The properties of tetraethyl lead proved vital to the Allies during World War II. Advances in aviation fuel increased power and efficiency, resulting in the production of 100-octane aviation gasoline shortly before the war.

Phillips Petroleum — later ConocoPhillips — was involved early in aviation fuel research and had already provided high-gravity gasoline for some of the first mail-carrying airplanes after World War I.

Phillips Petroleum produced tetraethyl leaded aviation fuels from high-quality oil found in Osage County, Oklahoma, oilfields.

Phillips Petroleum produced aviation fuels before it produced automotive fuels. The company’s gasoline came from the high-quality oil produced from Oklahoma’s Seminole oilfields and the 1917 Osage County oil boom.

Although the additive’s danger to public health was underestimated for decades, tetraethyl lead has remained an ingredient of 100-octane “avgas” for piston-engine aircraft.

Tetraethyl Lead’s Deadly Side

Leaded gasoline was extremely dangerous from the beginning, according to Deborah Blum, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science writer. “GM and Standard Oil had formed a joint company to manufacture leaded gasoline, the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation,” she noted in a January 2013 article. Research focused solely on improving the formula, not on the danger of the lead additive.

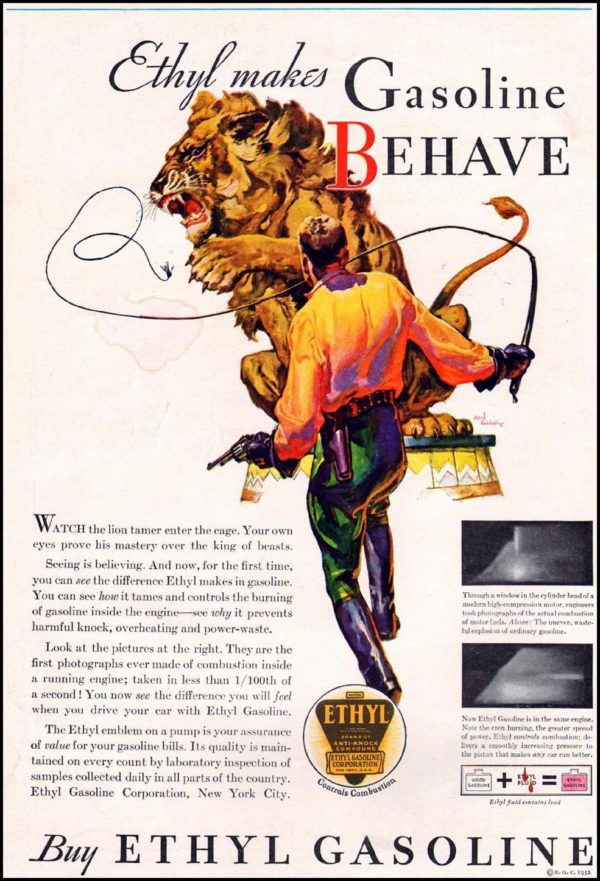

A 1932 magazine advertisement promoted the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation fuel additive as a way to improve high-compression engine performance.

“The companies disliked and frankly avoided the lead issue,” Blum wrote in “Looney Gas and Lead Poisoning: A Short, Sad History” at Wire.com. “They’d deliberately left the word out of their new company name to avoid its negative image.”

In 1924, dozens were sickened, and five employees of the Standard Oil Refinery in Bayway, New Jersey, died after they handled the new gasoline additive.

By May 1925, the U.S. Surgeon General called a national tetraethyl lead conference, Blum reported. An investigative task force was formed. Researchers concluded there was ”no reason to prohibit the sale of leaded gasoline” as long as workers were well protected during the manufacturing process.

So great was the additive’s potential to improve engine performance, the author notes, by 1926 the federal government approved continued production and sale of leaded gasoline. “It was some fifty years later — in 1986 — that the United States formally banned lead as a gasoline additive,” Blum added.

By the early 1950s, American geochemist Clair Patterson discovered the toxicity of tetraethyl lead; phaseout of its use in gasoline began in 1976 and was completed by 1986. In 1996, EPA Administrator Carol Browner declared, “The elimination of lead from gasoline is one of the great environmental achievements of all time.”

Learn more about high-octane aviation fuel in Flight of the Woolaroc.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: An Illustrated Guide to Gas Pumps (2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); Unleaded: How Changing Our Gasoline Changed Everything (2021). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website, expand historical research, and extend public outreach. For annual sponsorship information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2026 Bruce A. Wells. All right reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Ethyl Anti-Knock Gas.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/products/tetraethyl-lead-gasoline. Last Updated: December 4, 2025. Original Published Date: December 7, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Jan 16, 2026 | Petroleum Products

Phillips Petroleum invented a new plastic. Getting it from lab to market proved difficult. Enter Wham-O.

Research scientists in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1951 discovered how to make a durable, high-density polyethylene, and the marketing executives at their oil and natural gas company named it Marlex. But Phillips Petroleum sales reps searched in vain for buyers of the new plastic until the Wham-O toy company found it ideal for making hoops and flying platters.

Prompted by a post-World War II boom in demand for plastics, Phillips Petroleum Company invested $50 million to bring its own miracle product — Marlex — to market in 1954. With a high melting point and tensile strength, the synthetic polymer would stand out from the company’s thousands of patents.

(more…)