Meet Joe Roughneck

The 1950s advertising character that became a prestigious petroleum industry award.

Joe Roughneck’s rugged, square-jawed face first appeared in the 1950s as print advertisements for a tubular goods manufacturer. His helmeted visage in bronze became a petroleum industry award annually handed out to wildcatters “whose accomplishments and character represent the highest ideals of the oil and natural gas industry.”

Presented from 1955 to 2019 during conventions of a national oil and gas industry trade association, Joe’s Chief Roughneck statue symbolized the “leadership and integrity of individuals who have made a lasting impression on the energy industry.”

Torg Thompson, who drew the original Joe Roughneck bandaged-faced character in the 1950s, sculpted him for an annual industry award — and for display in Texas parks.

The award’s bronze bust began with Texas artist Torg Thompson (1905-1998) and the Lone Star Steel Company, later U.S. Steel Tubular Products, a subsidiary of United States Steel. Thompson’s busts, sculpted from his character created for newspaper and magazine advertisements, also would be dedicated in Texas parks.

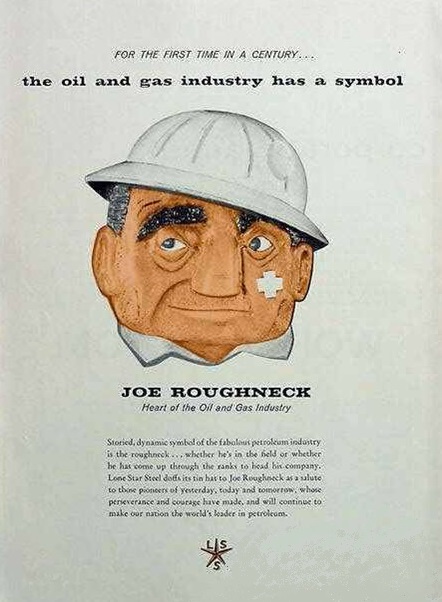

“Lone Star Steel doffs its tin hat to Joe Roughneck as a salute to those pioneers of yesterday, today and tomorrow, whose perseverance and courage have made, and will continue to make our nation the world’s leader in petroleum,” declared a 1959 Lone Star Steel magazine ad.

Recipients of the pipe manufacturer’s “Chief Roughneck Award” — first presented to independent producer R.E. (Bob) Smith in 1955 — included Harold Hamm, George Mitchell, Dean McGee, H.L Hunt, and W.A. “Monty” Moncrief (see Chief Roughneck Award Winners to view all recipients since 1955).

The advertising character’s battered face became popular in America’s oilfields, prompting Lone Star Steel executives to proclaim, “Joe doesn’t belong to us anymore. He’s as universal as a rotary rig.”

The character began its career on the scratch pad of Thompson, an artist known for the 124-by-20-foot mural, “Miracle at Pentecost,” at the Biblical Arts Center in Dallas (destroyed by fire in 2005). For Lone Star Steel Company ads, Thompson portrayed Joe with the countenance of a man who had spent long hours working in the oilfield.

In 1959, Lone Star Steel Company, an oilfield tubular goods manufacturer, produced this magazine advertisement featuring Joe Roughneck, the “Heart of the Oil and Gas Industry.”

“Joe’s jaw was squarely set to denote determination, his nose flattened as a souvenir of the rollicking life of a boom town. His eyes indicate the kindness and generosity of his breed. His mouth wore the trace of a smile, but there was a quizzical expression of one who had to see to believe,” notes a small museum in the heart of the East Texas oilfield.

“When the completed picture came into being on canvas, there was no doubt Joe was the heart of the oil patch,” the Depot Museum in Henderson adds.

Joe has been saluted by two governors of Texas, named “Man of the Month” by a popular magazine, and has been the subject of countless newspaper articles, along with many radio and television commentaries. Joe also became the mascot of the White Oak Roughnecks, a high school football team of another East Texas oilfield community.

“Joe’s likeness has adorned the world’s largest golf trophy and once decorated an international oil exposition,” the Depot Museum concludes.

At the Gaston Museum in Joinerville, Texas, a Joe Roughneck memorial was dedicated “to the pioneers of the Great East Texas oilfield.” The October 1930 discovery well is just 1.75 miles away — and still producing for the Hunt Oil Company.

Joe still serves as a symbol for petroleum clubs that “recognize the pioneers of yesterday and today whose perseverance and courage made our nation the world’s leader in petroleum.”

Presented at the annual meeting of the Independent Petroleum Association of America, Joe’s head now sits atop oilfield monuments in Texas: Joinerville (1957), Conroe (1957), Boonsville (1970), and Kilgore (1986) — where he greets visitors to the East Texas Oil Museum.

Joe Roughneck in Joinerville

This, the first Joe Roughneck monument, was erected in Pioneer Park at the Gaston Museum and Community Outreach in Joinerville, seven miles west of Henderson. The monument includes a time capsule sealed at the dedication on March 17, 1957, and to be opened in 2056. The capsule reportedly will tell future generations about the East Texas oilfield discovered by Columbus Marion “Dad” Joiner in early October 1930.

Joiner’s Daisy Bradford No. 3, discovery well for this prolific field, is nearby — less than two miles from the Gaston Museum. Production from the East Texas field exceeded five billion barrels of oil by 1993. Many modern waterflooding technologies were shaped by the giant field, and hundreds of marginal wells continue to produce there.

Joe Roughneck in Conroe

In Conroe, about 40 miles north of Houston, Joe Roughneck rests on a monument in Candy Cane Park at the Heritage Museum of Montgomery County. He commemorates the discovery of a 19,000-acre field by George Strake in 1931 – “and others who envisioned an empire, dared to seek it, and discovered the Conroe oilfield.”

The Joe Roughneck monument in Conroe, Texas, is next to a miniature derrick protected by Plexiglas — and information about Montgomery County, where “whispers of oil discovery started in the early 1900s.”

The monument recognizes the completion of Strake’s Conroe oilfield-discovery well in June of 1932. The “Conroe Courier” headlines proclaimed, “Strake Well Comes In. Good for 10,000 Barrels Per Day.”

The Conroe oilfield led to major technology developments after Strake found the oil sands to be natural gas-charged, shallow – and dangerously unstable. By 1993, the 17,000-acre Conroe oilfield will have produced more than 717 million barrels of oil (see Technology and the Conroe Crater).

Joe Roughneck in Boonsville

Governor Preston Smith dedicated Boonsville’s Joe Roughneck on October 26, 1970 — the 20th anniversary of the Boonsville natural gas field discovery.

The field’s 1945 discovery well, Lone Star Gas Company’s B.P. Vaught No. 1, produced 2.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas in its first 20 years. By 2001, the field — located in the Fort Worth Basin in north-central Texas — had produced 3.1 trillion cubic feet of gas and 17 million barrels of condensate from 3,500 wells in the field.

Boonsville’s Joe Roughneck statue can be found on Farm to Market Road 920 about 13 miles southwest of Bridgeport in southwestern Wise County.

Joe Roughneck in Kilgore

Kilgore hosts a Joe Roughneck erected on March 2, 1986, in a downtown plaza, celebrating the “boomers” who settled in Kilgore during the 1930s. When Kilgore’s monument committee first approached Lone Star Steel, it learned the Joe Roughneck cast had been destroyed in a fire. Lone Star Steel allowed use of the original mold to produce the monument.

During the East Texas boom, Kilgore had the densest number of wells in the world. Today’s World’s Richest Acre Park displays a pumping unit and the city has restored dozens of derricks from Kilgore’s boomtown birth – a story told at the East Texas Oil Museum.

As the Depot Museum’s exhibit concluded, Joe Roughneck has remained: “Rough and tough, sage and salty, capable and reliable, shrewd but honest. Joe has throughout his lifetime symbolized the determination of the American petroleum industry, reaffirming the indomitable spirit of Chief Roughnecks the world over, past, present and future.”

Joe Roughneck’s iconic advertisement creation should also credit former Lone Star Steel Vice President L.D. “Red” Webster, according to Michael Webb, spouse of Webster’s daughter Rebel Webster (1959-2021). Webb emailed the American Oil & Gas Historical Society and explained he was categorizing unique artifacts and other historic items related to the career of his late wife’s father.

In addition to the statues given to the Chief Roughneck Award winners since 1955, Webb reports Joe Roughneck is preserved by artifacts that include “pins, awards, tchotchkes, papers, plaques, photos of Red, and an original plaster bust of Joe Roughneck.”

In Washington, D.C., a 12-inch Joe Roughneck bronze bust is preserved in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum Institution.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: A Wildcatter’s Trek: Love, Money and Oil (2016 by 1995 Chief Roughneck Gene Ames Jr.); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information: Article Title: “Meet Joe Roughneck.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells, Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/petroleum-art/joe-roughneck. Last Updated: October 17, 2025. Original Published Date: March 11, 2005.