by Bruce Wells | Jul 23, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

Oilfield service provider Zero Hour Bomb Company in 1949 introduced its “cannot backlash” fishing reel.

Zebco oilfield history began well before 1947 when Jasper R. Dell Hull walked into the Tulsa offices of the Zero Hour Bomb Company. The amateur inventor from Rotan, Texas, carried a piece of plywood with nails arranged in a circle wrapped in line. His device included a coffee-can lid that could spin.

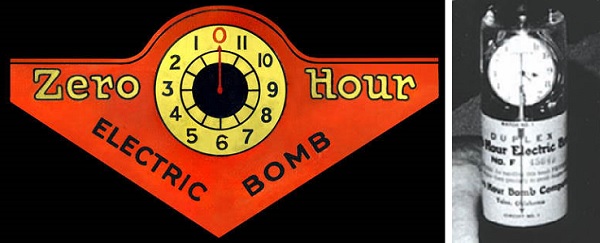

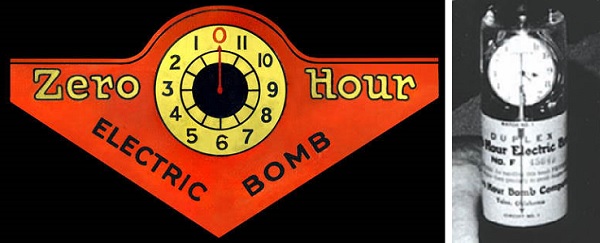

Hull, known by his friends as “R.D.,” had an appointment with executives at the Oklahoma oilfield service company. Incorporated in 1932, the Zero Hour Bomb Company was a leading manufacturer of dependable electric timer bombs used for fracturing geologic formations. The company designed and patented innovative technologies for “shooting” wells to increase oil and natural gas production.

In 1932, the oilfield service company Zero Hour Bomb Company began manufacturing electric time bombs in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Photos courtesy Zebco.

Zero Hour Bomb Company’s timer controlled a mechanism with a detonator inside a watertight casing. The downhole device could be pre-set to detonate a series of blasting caps, which set off the well’s main charge, shattering rock formations.

Hull’s 1947 visit proved timely for Zero Hour Bomb Company, because post World War II demand for its electrically triggered devices had declined. With the military no longer needing oil to fuel the war, the U.S. petroleum industry faced a major recession.

The company and other once booming Oklahoma service companies were reeling, and the future did not look good.

“Vast fossil fuel reserves beneath other Middle Eastern nations were being unlocked,” noted journalist Joe Sills in a 2014 article. With OPEC beginning to take shape, Texas and Oklahoma-based oil production could only look forward to taking “a decades-long backseat to foreign oil.”

Further, with company patents expiring in 1948, “the Zero Hour Bomb Company needed a solution,” explained Sills, an editor for Fishing Tackle Retailer. After examining Hull’s contraption, a prototype fishing reel, the company hired him for $500 a month.

Meanwhile, as “fishing” petroleum wells helped recover downhole tools, Hull received a patent that transformed the Zero Hour Bomb Company — and sport fishing in America.

Downhole Patents

Beginning in the early 1930s, Zero Hour Bomb engineers patented many innovative oilfield products. A 1939 design for an “Oil Well Bomb Closure” facilitated the assembly of an explosive device capable of withstanding extreme pressures submerged deep in a well.

A 1940 innovation provided a hook mechanism for safely lowering torpedoes into wells. The locking method could “positively prevent premature release of the torpedo while it is being lowered into the well.”

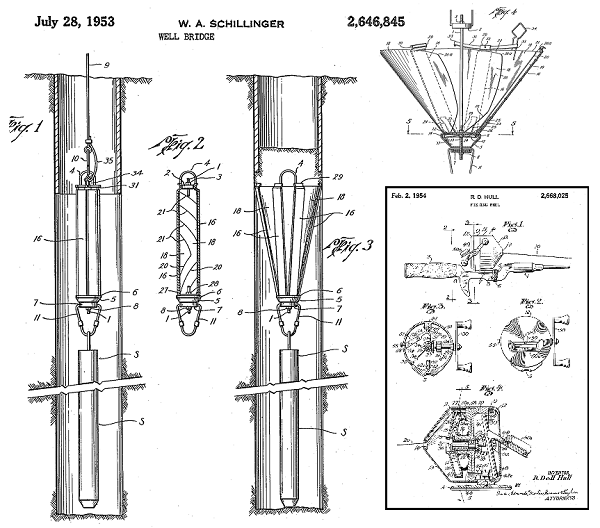

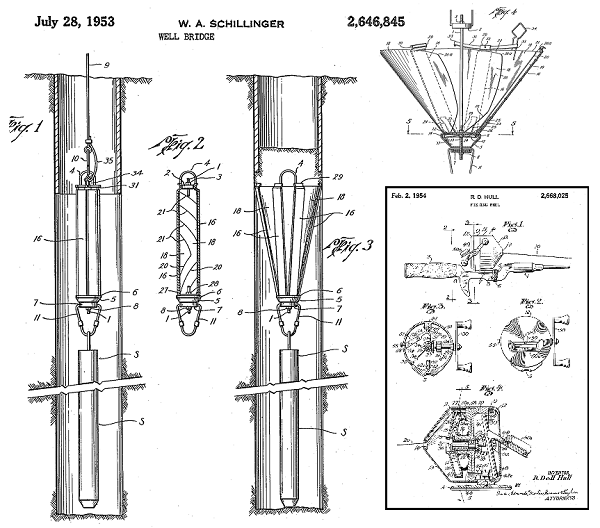

The July 28, 1953, patent for a canvas “well bridge” would be among the last Zero Hour Bomb Company received as an oilfield equipment manufacturer, thanks to R.D. Hull’s late-1940s design for a fishing reel (insert) illustrated in his February 2, 1954, patent.

The separate patent in 1941 improved positioning blasting cartridges using a plugging device made of canvas. It looked like an upside-down umbrella that automatically opened, “when the time bomb or weight reached a position at the bottom of the well.”

In 1953, an improved “well bridge” design took the concept even further, but it would be the last patent Zero Hour Bomb received as an oilfield equipment manufacturer. By then, the earliest model of Hull’s new “cannot backlash” reel attracted large crowds at sports shows.

Zebco Reels

“After trying to design ‘brakes’ for bait-casting reels, and even failing at launching one fishing reel company, Hull hit on a better way one day as he watched a grocery store clerk pull string from a large fixed spool to wrap a package,” reported Lee Leschper in a 1999 Amarillo Globe-News article.

Zero Hour Bomb Company’s first “cannot backlash” reel made its public debut at a Tulsa sports expo in June 1949.

Hull realized he needed a cover to keep the line from spinning off the reel itself and soon developed a prototype, Leschper noted.

“Zero Hour officials asked two company employees who were avid fishermen for their opinions on the reel,” Leschper explained. “One tied his set of car keys to the end of the line and sent a cast flying through one of the windows in the plant. The other sent a cast high over the building. All were impressed.”

Given his own Hull-designed fishing reel at about age six, Leschper recalled, the “tiny black pushbutton reel” came with 6 lb. monofilament line (see Nylon, A Petroleum Polymer) and a four-foot hollow fiberglass rod. His small rig included a hard, yellow plastic practice plug. “I wore it down to a nub pitching it across the hard-baked grass in our front yard.”

White House security officials in 1956 quickly submerged in water a Zero Hour Bomb Company package addressed to President Eisenhower. Photo courtesy Fishing Tackle Retailer magazine.

Earlier, Hull had tested several designs before developing a manufacturing process; the first reel debuted on May 13, 1949. Called the Standard, it made its public debut at a Tulsa sports expo in June. By 1954, the reel included the simple push-button system used today.

In 1961, Brunswick Corporation acquired Zebco — and introduced the 202 ZeeBee Spincast, “an instant classic.”

White House Insecurity

The regional marketing name — Zebco — became popular, but the bottom of each reel’s foot remained stamped with the name of the manufacturer: Zero Hour Bomb Company. The official name change to Zebco came in 1956 — soon after a friend of President Dwight D. Eisenhower asked the company to send a reel to the president.

According to a Zebco company history, when White House security officers saw the package labeled “Zero Hour Bomb Company,” they plunged it into a tub of water and called the bomb squad. After changing its name to Zebco, the company left the oilfield for good.

Jasper R. Dell “R.D.” Hull joined the Sporting Goods Industry Hall of Fame in 1975 after receiving more than 35 patents. At the time of his induction, 70 million Zebco reels had been sold. He retired from the former oilfield time-bomb company in January 1977 after being diagnosed with cancer and died in December at age 64.

___________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Zebco Reel Oilfield History.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/zebco-reel-oilfield-history. Last Updated: July 23, 2025. Original Published Date: February 20, 2018.

by Bruce Wells | Jul 13, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

As the U.S. petroleum industry expanded following the January 1901 “Lucas Gusher” at Spindletop Hill in Texas, service company pioneers like Carl Baker and Howard Hughes brought new technologies to oilfields.

Baker Oil Tools and Hughes Tools specialized in maximizing petroleum production, as did oilfield service company competitors Schlumberger, a French company founded in 1926, and Halliburton, which began in 1919 as a well-cementing company.

R.C. “Carl” Baker Sr.

Baker Oil Tool Company (later Baker International) had been founded by Reuben Carlton “Carl” Baker Sr., who among other inventions patented a cable-tool drill bit in 1903 after founding the Coalinga Oil Company in Coalinga, California.

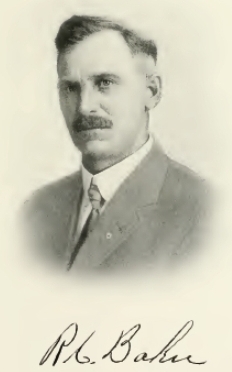

A 1919 portrait of Baker Tools Company founder R.C. “Carl” Baker (1872 – 1957).

The oil wells Carl Baker had drilled near Coalinga encountered hard rock formations that caused problems with casing, so he developed an offset cable-tool bit allowing him to drill a hole larger than the casing. He also patented a “Gas Trap for Oil Wells” in 1908, a “Pump-Plunger” in 1914, and a “Shoe Guide for Well Casings” in 1920.

Coalinga was “every inch a boom town and Mr. Baker would become a major player in the town’s growth,” according to the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum. He also organized several small oil companies and the local power company and established a bank.

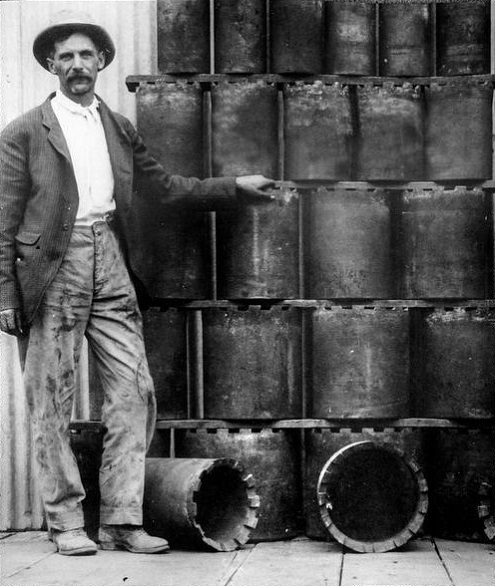

After drilling wells in the Kern River oilfield, Baker added to his technological innovations on July 16, 1907, when he was awarded a patent for his Well Casing Shoe (No. 860,115), a device ensuring uninterrupted flow of oil through a well. His invention revolutionized oilfield production.

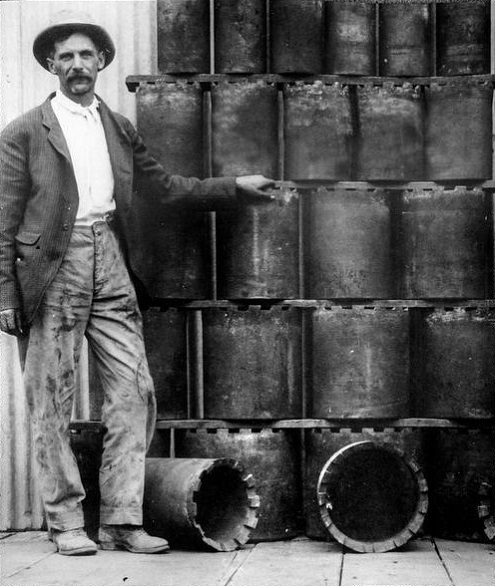

R.C. “Carl” Baker standing next to Baker Casing Shoes in 1914. Photo courtesy R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

In 1913, Baker organized the Baker Casing Shoe Company (renamed Baker Tools two years later). He opened his first manufacturing plant in Coalinga.

When Baker Tools headquarters moved to Los Angeles in the 1930s, the building remained a company machine shop. It was donated by Baker to Coalinga in 1959. Two years later, the original machine shop and office of Baker Casing Shoe reopened as the R.C. Baker Memorial Museum.

By the time Carl Baker Sr. died in 1957 at age 85, he had been awarded more than 150 U.S. patents in his lifetime. “Though Mr. Baker never advanced beyond the third grade, he possessed an incredible understanding of mechanical and hydraulic systems,” reported the former Coalinga museum.

Baker Tools became Baker International in 1976 and Baker Hughes after the 1987 merger with Hughes Tool Company.

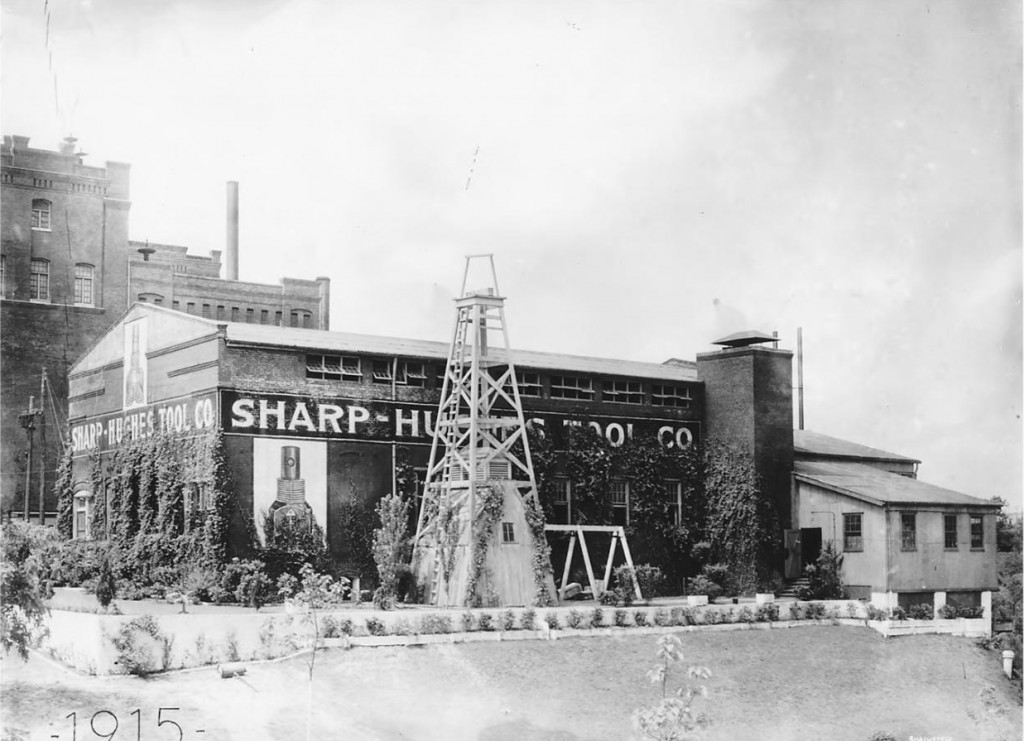

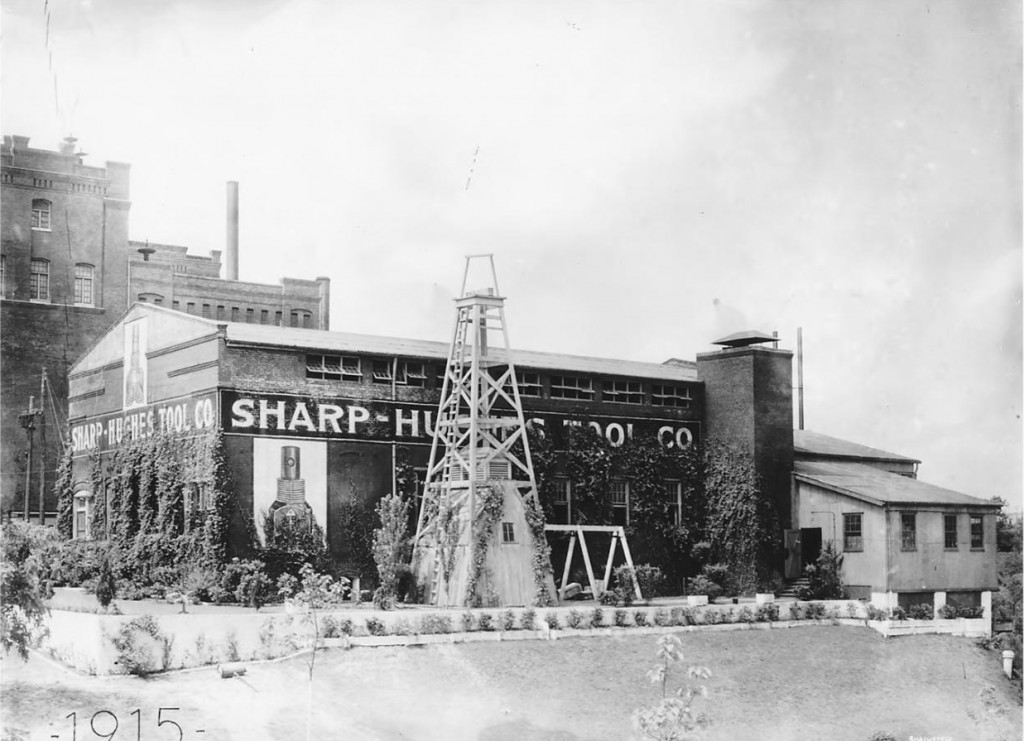

The Houston manufacturing operations of Sharp-Hughes Tool at 2nd and Girard Streets in 1915. The site is on the campus of the University of Houston–Downtown. Photo courtesy Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library.

Howard Hughes and Walter Sharp

The Hughes Tool Company began in 1908 as the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company, founded by Walter B. Sharp (1870–1912) and Howard R. Hughes, Sr.

Sharp was an experienced Texas oilfield pioneer who in 1893 drilled for the Gladys City Oil and Gas Manufacturing Company at Beaumont, Texas. The exploratory well on Spindletop Hill did not find oil, but it helped lead to the giant oilfield’s discovery in 1901, according to Texas State Historical Association (TSHA).

In 1896, Sharp was one of the drillers at Corsicana when the state’s first commercial oilfield was developed. While there, he met Joseph “J.S.” Cullinan, who became a lifelong friend. Cullinan in 1902 founded the Texas Company (see Sour Lake produces Texaco).

Sharp and Hughes in 1907 drilled test wells at Goose Creek/ “When both wells had to be abandoned because of the hard rock encountered, the two men began to consider the possibility of developing a roller rock bit. It was eventually arranged for Hughes to proceed with the designing and construction of a bit, with capital provided equally by Sharp and Cullinan.

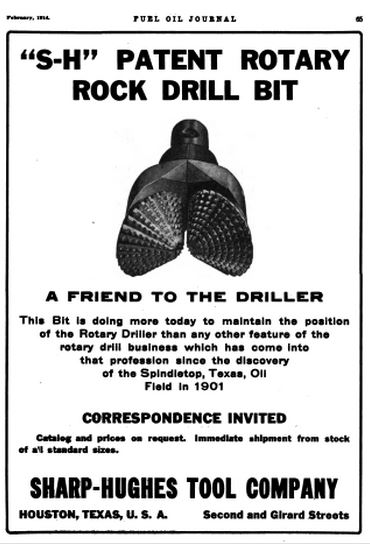

Rotary drilling bits shaped like fishtails became obsolete in 1909 when the two inventors introduced a dual-cone roller bit. They created a bit “designed to enable rotary drilling in harder, deeper formations than was possible with earlier fishtail bits,” according to a Hughes historian. Secret tests took place on a drilling rig at Goose Creek, south of Houston.

Hard Rock at Goose Creek

“In the early morning hours of June 1, 1909, Howard Hughes Sr. packed a secret invention into the trunk of his car and drove off into the Texas plains,” noted Gwen Wright of History Detectives in 2006. The drilling site was near Galveston Bay. Rotary drilling “fishtail ” bits of the time were “nearly worthless when they hit hard rock.”

The new technology would soon bring faster and deeper drilling worldwide, helping to find previously unreachable oil and natural gas reserves. The dual-cone bit also created many Texas millionaires, explained Don Clutterbuck, one of the PBS show’s sources.

“When the Hughes twin-cones hit hard rock, they kept turning, their dozens of sharp teeth (166 on each cone) grinding through the hard stone,” he added.

Although several inventors tried to develop better rotary drill bit technologies, Sharp-Hughes Tool Company was the first to bring it to American oilfields. Drilling times fell dramatically, saving petroleum companies huge amounts of money.

Howard Hughes Sr. (1869 – 1924) on August 10, 1909, was awarded a U.S. patent for a dual-cone drill bit that could crush hard rock.

The Society of Petroleum Engineers has noted that about the same time Hughes developed his bit, Granville A. Humason of Shreveport, Louisiana, patented the first cross-roller rock bit, the forerunner of the Reed cross-roller bit.

Biographers have noted that Hughes met Granville Humason in a Shreveport bar, where Humason sold his roller bit rights to Hughes for $150. The University of Texas Center for American History Collection includes a 1951 recording of Humason talking about that chance meeting. He recalled spending $50 of his sale proceeds at the bar that evening.

After Walter Sharp died in 1912, his widow Estelle Sharp sold her 50 percent share in the company to Hughes. It became Hughes Tool in 1915. Despite legal action between Hughes Tool and the Reed Roller Bit Company in the late 1920s, Hughes prevailed and his oilfield service company prospered.

Hughes Tool

By 1934, Hughes Tool engineers designed and patented the three-cone roller bit, an enduring design that remains much the same today. Hughes’ exclusive patent lasted until 1951, which allowed his Texas company to grow worldwide. More innovations (and mergers) would follow.

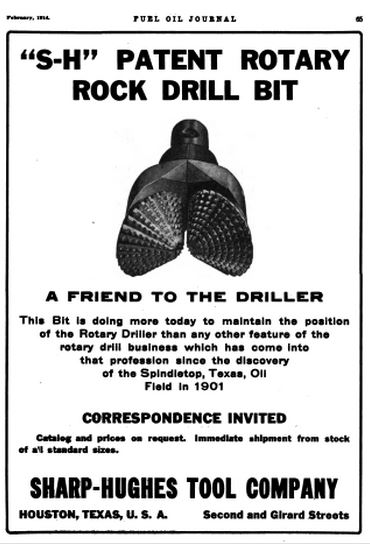

A February 1914 advertisement for the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company in Fuel Oil Journal.

Frank Christensen and George Christensen had developed the earliest diamond bit in 1941 and introduced diamond bits to oilfields in 1946, beginning with the Rangley field of Colorado. The long-lasting tungsten carbide tooth came into use in the early 1950s.

After Baker International acquired Hughes Tool Company in 1987, Baker Hughes acquired the Eastman Christensen Company three years later. Eastman was a world leader in directional drilling.

When Howard Hughes Sr. died in 1924, he left three-quarters of his company to Howard Hughes Jr., then a student at Rice University. The younger Hughes added to the success of Hughes Tool while becoming one of the richest men in the world. His many legacies include founding Hughes Aircraft Company and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Learn more in Making Hole – Drilling Technology.

Oilfield Service Competition

A major competitor for any energy service company, today’s Schlumberger Limited can trace its roots to Caen, France. In 1912, brothers Conrad and Marcel began making geophysical measurements that recorded a map of equipotential curves (similar to contour lines on a map). Using very basic equipment, their field experiments led to the invention of a downhole electronic “logging tool” in 1927.

After developing an electrical four-probe surface approach for mineral exploration, the brothers lowered another electric tool into a well. They recorded a single lateral-resistivity curve at fixed points in the well’s borehole and graphically plotted the results against depth – creating first electric well log of geologic formations.

Meanwhile, another service company in Oklahoma, the Reda Pump Company had been founded by Armais Arutunoff, a close friend of Frank Phillips. By 1938, an estimated two percent of all the oil produced in the United States with artificial lift, was lifted by an Arutunoff pump.

Learn more in Inventing the Electric Submersible Pump (also see All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology).

_______________________

Recommended Reading: History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2007); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Carl Baker and Howard Hughes.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/carl-baker-howard-hughes. Last Updated: July 17, 2025. Original Published Date: December 17, 2017.

by Bruce Wells | May 21, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

Marketing icon “Dino” and friends introduced children to wonders of the Mesozoic era courtesy of Sinclair Oil.

Harry Ford Sinclair established his petroleum company in 1916, making it one of the oldest continuous names in the U.S. energy industry. Appearing among other Sinclair Oil Company dinosaurs during the 1933-1934 World’s Fair in Chicago, “Dino” became a marketing icon whose popularity with children remains today. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | May 19, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

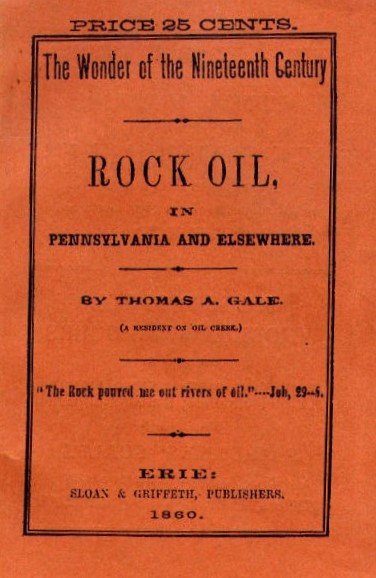

Less than 10 months after Edwin L. Drake and his driller William “Uncle Billy” Smith completed the first commercial U.S. oil well on August 27, 1859, along Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, Thomas A. Gale wrote a detailed study about rock oil — and helped launch the petroleum age.

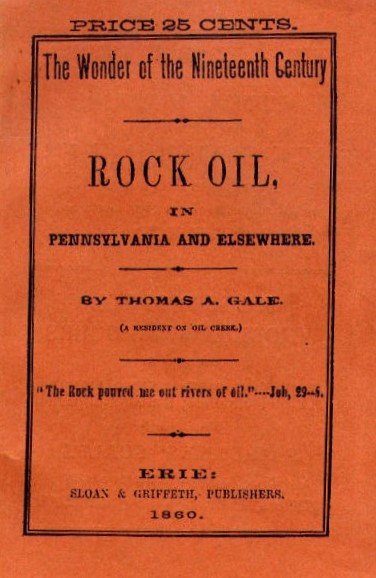

Published in 1860, The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere described a radical fuel source for the popular lamp fuel kerosene, which had been made from coal for more than a decade.

“Those who have not seen it burn may rest assured its light is no moonshine; but something nearer the clear, strong, brilliant light of day,” Gale declared in his 25-cent pamphlet printed in Erie by Sloan & Griffith Company.

Thomas Gale’s 80-page pamphlet in 1860 marked the beginning of the petroleum age, illuminated with kerosene lamps.

“In other words, rock oil emits a dainty light; the brightest and yet the cheapest in the world; a light fit for Kings and Royalists, and not unsuitable for Republicans and Democrats,” Gale added.

Oil in Rocks

Gale’s descriptions of the value of petroleum helped launch investments in new exploration companies, especially as he noted the commercial qualities of Pennsylvania oil for refining into kerosene, the distilled “coal oil” invented in 1848 by Canadian chemist Abraham Gesner.

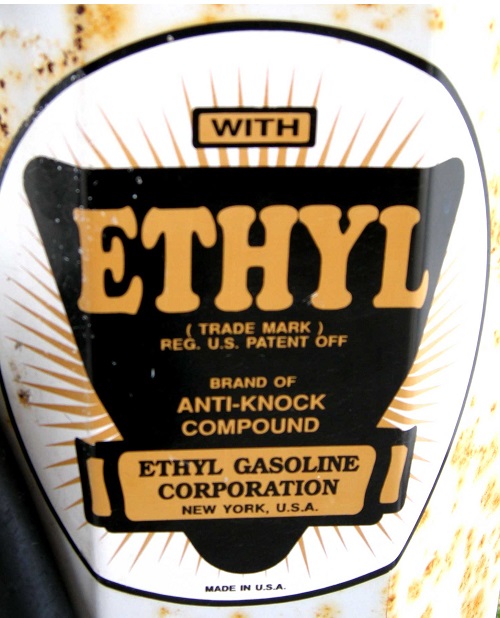

Historians regard the 80-page publication as the first book about America’s petroleum industry. The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere was almost forgotten until 1952, when the Ethyl Corporation of New York republished the work. Only three original copies were known to exist.

“Not by the widest stretch of the imagination could Thomas Gale have realized, when he put down his pen on June 1, 1860, that he had written a book destined to become one of the rarest of all oil books,” proclaimed the Ethyl historian when the company republished Gale’s book.

Ethyl Corporation noted the scarcity of copies of the book had prevented “all but a few historians” from giving the book the attention it deserved.

“Gale wrote his book to satisfy a public desire for more information about petroleum. Newspapers had carried belated accounts of Drake’s discovery well, and the mad scramble for oil that followed, but actually the world knew little about petroleum.”

“The Rock poured…”

The book’s 11 chapters explain practical aspects of the new petroleum industry. Chapters one and two, “What is Rock Oil?” and “Where is the Rock Oil found?” were followed by “Geological Structure of the Oil Region.”

Chapters four through six explained the early technologies (and costs) for pumping the oil, while the next two chapters examine “Uses of Rock Oil.” The final three chapters offered “Sketches of several oil wells,” “History of the Rock Oil Enterprise,” and “Present condition and prospects of Rock Oil interests in different localities.”

Chapter three in The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere features the “geological structure of the oil region,” today part of Oil Creek State Park in northwestern Pennsylvania.

Originally published by Sloan & Griffith of Erie, Pennsylvania, the 1860 cover noted the author as “a resident of Oil Creek” and included a biblical quote, “The Rock poured me out rivers of oil,” from Job, 29:6.

In addition to mysteriously burning gasses and “tar pits,” explorers for millennia have referenced signs of coal, bitumen, and substances very much like petroleum — a word derived from the Latin roots of petra, meaning “rock” and oleum meaning “oil.”

But did Thomas Gayle’s 1860 work produce the first book about oil as Ethyl Corporation historians believed when the company reprinted it in 1952? In fact, there have been many references to natural oil seeps recorded millennia ago (including in the Bible), according to a geologist who has researched the earliest sightings of petroleum.

Illuminating Petroleum

Several years before the 1859 oil discovery in Pennsylvania, businessman George Bissell hired a prominent Yale chemist to study the potential of oil and its products to convince potential investors (see George Bissell’s Oil Seeps).

“Gentlemen, it appears to me that there is much ground for encouragement in the belief that your company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive processes, they may manufacture very valuable products,” reported Benjamin Silliman Jr. in 1855.

Silliman’s groundbreaking “Report on the Rock Oil, or Petroleum, from Venango Co., Pennsylvania, with Special Reference to its Use for Illumination and Other Purposes,” convinced the petroleum industry’s earliest investors to drill at Titusville. Cable-tool technology developed for brine wells would drill the well.

According to historian Paul H. Giddens in the 1939 classic, The Birth of the Oil Industry, Silliman’s 1855 report, “proved to be a turning-point in the establishment of the petroleum business, for it dispelled many doubts about its value.”

The Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company would evolve into the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut, which became America’s first oil company after Drake completed the first U.S. commercial well drilled seeking oil in 1859.

Rock Oil Products

In addition to providing oil for refining into kerosene lamps (and someday rockets), oilfield discoveries led to many products. Early petroleum products included axle greases, an oilfield paraffin balm, and in Easton, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons.

Further, oil offered an improved asphalt prior to the first U.S. auto show in November 1900 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

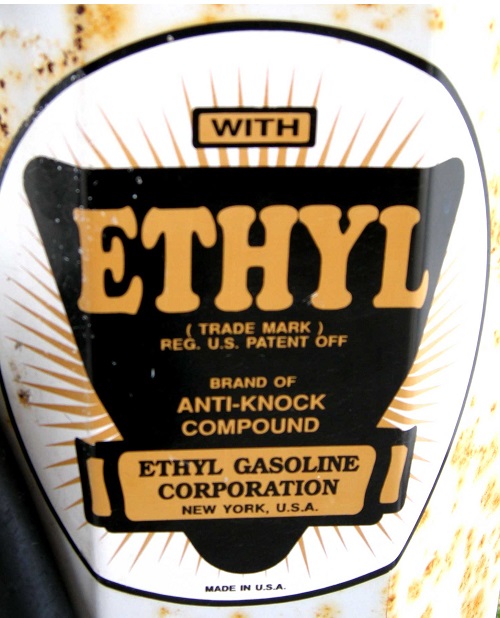

Ethyl Corporation was established in 1923 by General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey,

Responding to consumer demand for better automobile gasoline, General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey established the Ethyl Corporation in 1923. The company initially downplayed the danger of tetraethyl lead. Leaded gas would be banned for use in cars in the 1970s

Importantly, high-octane leaded aviation fuel proved vital for victory in World War II — and the additive still fuels many piston-engine aircraft and racecars.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere (1952); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1939); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Oil Book of 1860.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/first-oil-book-of-1860. Last Updated: May 17, 2025. Original Published Date: May 31, 2020.

by Bruce Wells | May 7, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

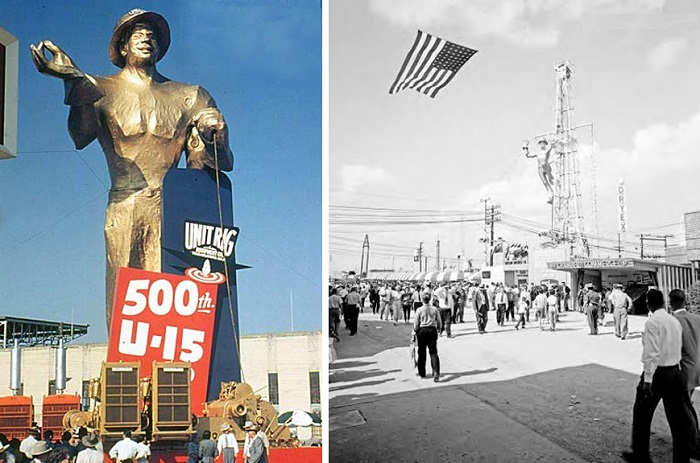

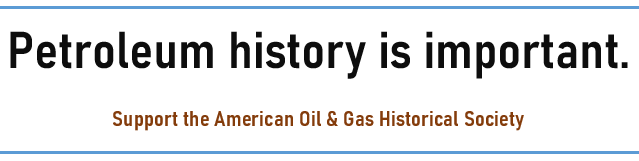

Erected for the 1953 International Expo, Tulsa’s towering roughneck grew into an Oklahoma landmark.

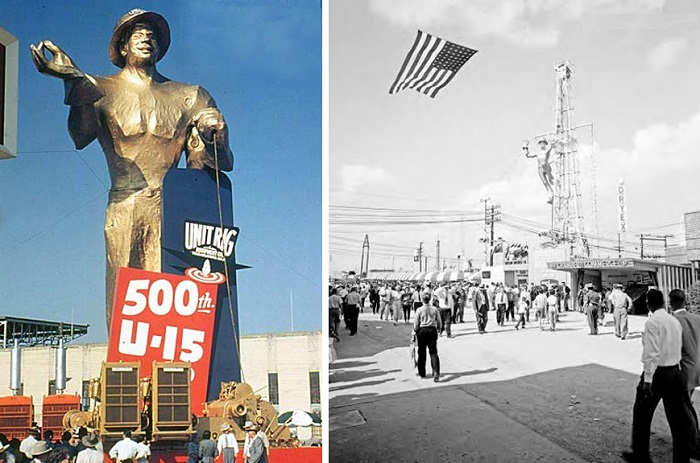

With an arm casually resting on a steel derrick, the 76-foot giant cannot be missed by visitors to the Tulsa County Fairgrounds. Popularly known as the “Golden Driller,” the first version of the 22-ton Oklahoma roughneck appeared in May 1953 as an oilfield supply company promotion during the Tulsa International Petroleum Exposition.

The leading oil and natural gas equipment expo, which began in 1923 as the International Petroleum Exposition and Congress, took place for decades at the Tulsa County Free Fair site. Tulsa independent producer William Skelly established the expo while he was serving as president of the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce.

In 1953, a golden “roustabout” statue conceived by the Mid-Continent Supply Company of Fort Worth, Texas, proved so popular it returned in 1959 after receiving a makeover.

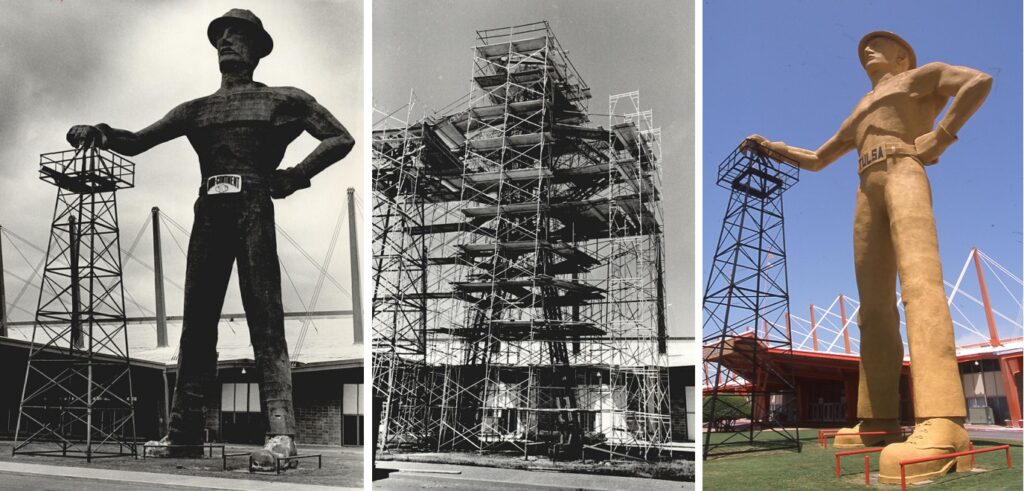

Designated an Oklahoma state monument in 1979, the Golden Driller was permanently installed for the 1966 International Petroleum Exposition in Tulsa. Photo by Bruce Wells.

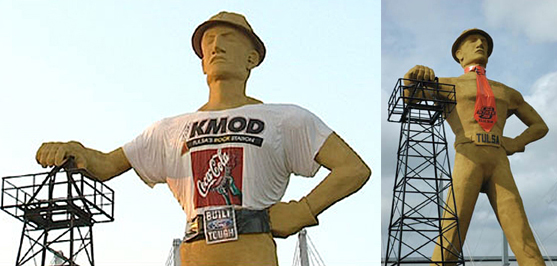

Another refurbishment and then neglect followed the fortunes of the petroleum industry. But civic leaders now proclaim the the Tulsa driller the most photographed landmark in the city once known as the “Oil Capital of the World.”

Although Mid-Continent Supply’s smaller first statue of 1952 impressed expo visitors, it was the 1959 version with an oilfield worker climbing a derrick that led to Tula’s current Golden Driller. “This time he was much more chiseled and detailed and was placed climbing a derrick and waving,” explained a volunteer for the Tulsa Historical Society in 2010.

The original Golden Driller of 1953, left, proved so popular that a smaller, rig-climbing version (called The Roustabout) returned for the 1959 International Petroleum Exposition. The Tulsa fairgrounds opened in 1903. Images courtesy Tulsa Historical Society.

According to the society’s “Tulsa Gal,” the 1959 rig-climbing roustabout’s popularity inspired Mid-Continent Supply to donate it to the Tulsa County Fairgrounds Trust Authority when the international expo ended. Sometime during the next seven years, the giant was redesigned to better withstand the elements, she noted.

Taller and much stronger, the modern Golden Driller debuted in 1966 at Tulsa’s International Petroleum Exposition. The new look came from a Greek immigrant, George “Grecco” Hondronastas, an artist who had worked on the 1953 exposition’s hard-hatted statue.

According to writer Tony Beaulieu, Hondronastas was an eccentric and prolific artist who was proud of becoming a U.S. citizen through military service in World War I. He attended the Art Institute of Chicago and later became a professor. His design work included business promotions and parade floats.

Mid-Continent Supply Company constructed a permanent version in 1966 with steel rods to withstand up to 200 mph winds but more work would be needed. The giant was refurbished again in 1979, after it was designated an Oklahoma state monument.

Hondronastas came to Tulsa for the first time in 1953, “to help design and build an early version of the Golden Driller,” explained Beaulieu, who also noted the artist “fell in love with the city of Tulsa and later moved his wife and son from Chicago to a duplex near Riverview Elementary School, just south of downtown.”

The artist was immensely proud of designing the Golden Driller — “and he would tell that to anyone he met,” added his son Stamatis, quoted in Beaulieu’s 2014 article, “An Oil Town’s Golden Idol, “ in This Land magazine.

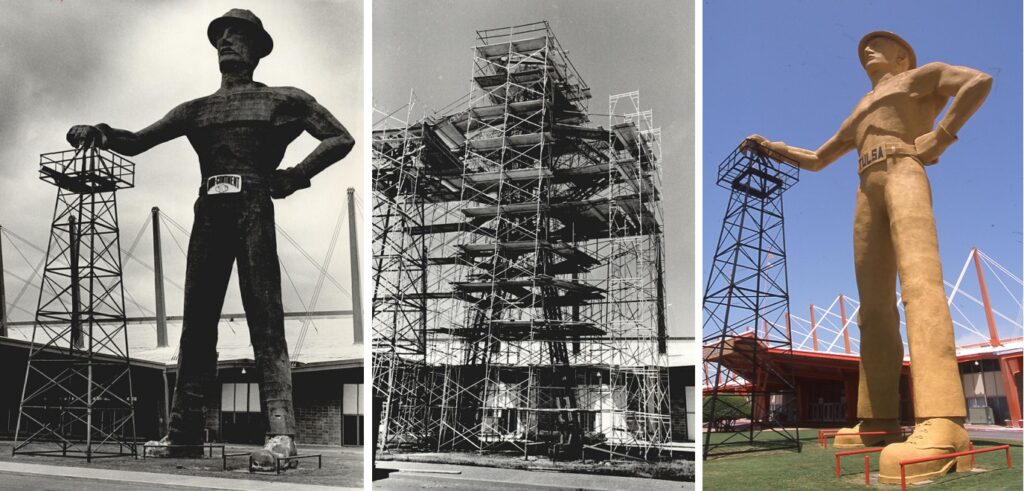

“The battered Golden Driller statue has been declared an official state monument,” noted the Daily Oklahoma more than a decade after Mid-Continent Supply donated its 1966 version to the Tulsa County Fairgrounds. Rebuilt in 1979 (center), the modern statue has was repainted in 2011. Photos courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

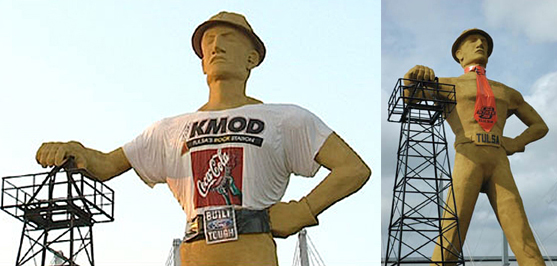

The late Tulsa photographer Walter Brewer documented construction of the giant with images later donated to the Tulsa Historical Society. Designated a state monument and refurbished again in 1979 (the year Hondronastas died), the statue as it appears today was permanently installed at East 21st Street and South Pittsburg Avenue.

The statue contains 2.5 miles of rods and mesh, along with tons of plaster and concrete. It can withstand up to 200 mph winds, “which is a good thing here in Oklahoma,” according to Tulsa Gal. It was painted it’s golden mustard shade in 2011,

Tulsa’s giant driller has sported t-shirts, belts, beads, neckties and other promotions during state fairs. A Covid-19 mask was added in the summer of 2020. Images courtesy the Tulsa Historical Society.

The Golden Driller’s right hand rests on an old production derrick moved from oilfields near Seminole, Oklahoma — a town that has its own extensive petroleum heritage.

Fully refurbished in the late 1970s, the Golden Driller — by now a 43,500-pound tourist attraction — is the largest free-standing statue in the world, according to Tulsa city officials. “Over time the Driller has seen the good and the bad,” said Tulsa Girl.

“He has been vandalized, assaulted by shotgun blasts and severe weather,” she added. “But he has also had more photo sessions with tourists than any other Tulsa landmark and can boast of many who love him all around the world.”

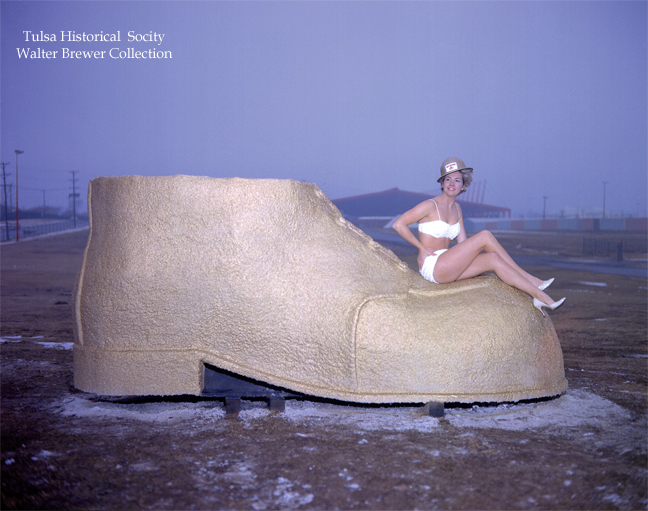

An unidentified model posed on one of the Golden Driller’s shoes, probably sometime during construction of the permanent version in time for the opening of Tulsa’s 1966 International Petroleum Exposition.

The Golden Driller, a symbol of the International Petroleum Exposition. Dedicated to the men of the petroleum industry who by their vision and daring have created from God’s abundance a better life for mankind. — Inscription on a plaque at the Golden Driller’s base.

An American Oil & Gas Historical Society 2007 Energy Education Conference and Field Trip in Oklahoma City included visits to oil museums in Seminole, Drumright and Tulsa — with a stop at the Golden Driller. Photo by Timothy G. Wells.

Although the first International Petroleum Exposition and Congress had no giant roughneck statue in 1923, the expo helped make Tulsa famous around the world. Leading oil and gas companies were attracted to Tulsa as early as 1901, six years before Oklahoma became a state (learn more in Red Fork Gusher).

An even bigger oilfield discovery arrived in 1905 on a farm south of the future oil capital. On November 22, 1905, the Ida Glenn No. 1 well erupted a geyser of oil southeast of Tulsa. The giant Glenn Pool field would forever change Tulsa and Oklahoma.

Learn more Tulsa history in the extensive collection of the Tulsa Historical Society.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Tulsa Oil Capital of the World, Images of America (2004); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America

(2004); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America (2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2000). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Golden Driller of Tulsa.” Authors: B.A. and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/golden-driller-tulsa. Last Updated: May 17, 2025. Original Published Date: March 1, 2006.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 5, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

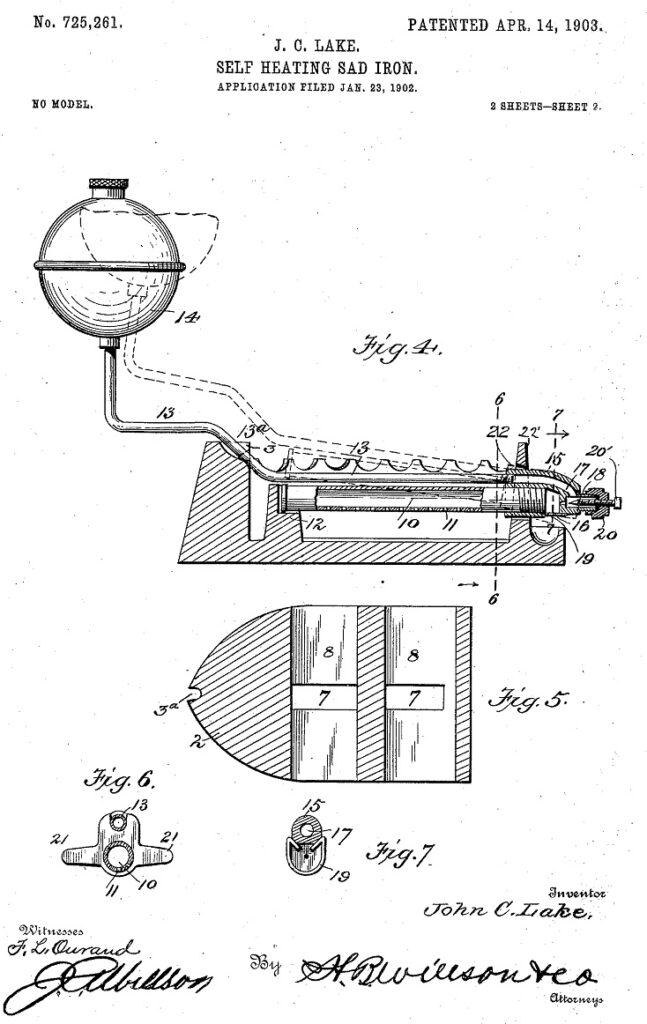

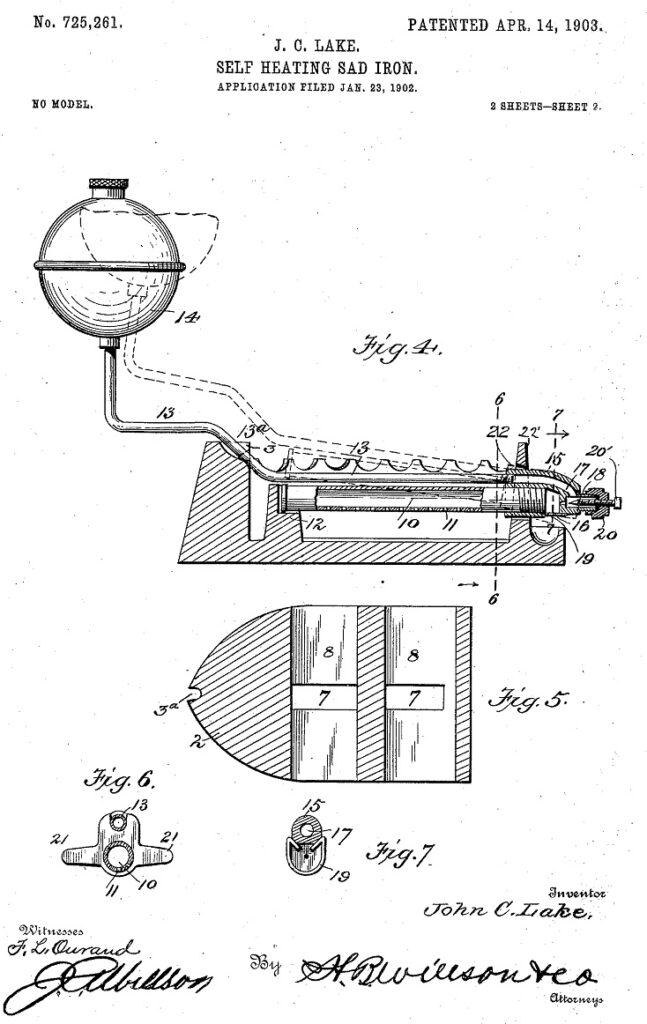

“Self-Heating Sad Irons” patented in 1903 used gasoline to make ironing easier.

On ironing day long before electricity, a row of sad irons could be found in the kitchen where the family’s cast-iron cook stove kept them hot. Three or four of these heavy “sadirons” — from the old English word meaning “solid” — cycled between the stove and a nearby ironing board.

With each sad iron weighing five to nine pounds, smoothing clothes led to an exhausting ironing routine. In 1872, Mary Florence Potts from Ottumwa, Iowa, patented a sad iron design with two pointed ends and a quick-change detachable walnut handle.

The 19-year-old housewife’s invention offered relief from blistered palms and was instantly popular nationwide. Thirty years later, a Civil War veteran brought another innovation to ironing.

Gasoline-fueled Sad Iron

John C. Lake, who served in the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War, patented (No. 725,261) a gasoline-fueled “Self-Heating Sad Iron” in April 1903.

Lake’s invention made the family fortune and brought prosperity to Big Prairie, Ohio, where he established the Monitor Sad Iron Company on the Pennsylvania Railroad line. The manufacturing company in Amish country would make petroleum-fueled sad irons for the next 50 years.

The 61-year-old inventor earlier had shared three woodworking tool patents with his father Abraham, but none led to production. Lake’s new gasoline-fired sad iron would bring easier ironing to households without electrical service, which in 1903 meant most of America.

As advertised, “Monitor Self-Heating Sad Irons” did not need the kitchen stove, maintained a steady temperature, and turned on and off with a knob. Two tablespoons of alcohol started the process and charged the reservoir delivery system.

“Save Half the Time, Half the Labor, and All the Worry of Laundry Day,” the ads proclaimed as consumers warmly welcomed the gasoline-fueled sad irons, which sold for $3.50 each.

Monitor Sad Iron Company expanded by licensing an army of sales agents. As the factory in Big Prairie grew, by 1920 the company could proclaim 850,000 in cumulative sales. In the 1930s, Monitor added a new brand (Royal) as Lake’s son Bertus received three patents for improvements.

Geologist Iron Man

Antique iron collector Prof. Kevin McCartney knows a lot about Monitor Sad Iron Company and its early competitors like Jubilee and Ideal. A professor of Geology at the University of Maine at Presque Isle, he also serves as director of the Northern Maine Museum of Science.

Since 2013, McCartney has posted more than 50 YouTube videos, “to educate and entertain the avid collector, antique shop owner, pickers and novices alike. Each video is a mini-lesson on a different topic about irons.”

In his Kevin Talks Irons number 54, “Firing up the 1903 Monitor gasoline iron,” he described how consumers preferred Monitor’s gasoline appliance — made with just three durable assemblies — because it was “simple, utilitarian, and economical.”

The Monitor Sad Iron Company’s patented self-heating design became “most common of the early gasoline irons.” Formerly a byproduct of kerosene refining, gasoline also had begun its transformation from “white gas” into an automobile fuel before Anti-Knock Ethyl and other additives added color.

Coleman Lamp Company entered the gasoline-fueled iron business in the 1920s. Based in Wichita, Kansas, Coleman began producing a self-heating iron while securing additional patents in 1940.

Products from Monitor, Coleman, Royal and others competed in catalog offerings and advertisements, especially for potential customers in rural, unelectrified regions. The self-heating appliances burned the basic white gas (naphtha). Coleman later branded and sold the fuel in one-gallon containers as Coleman Fuel.

Coleman Company quit manufacturing gasoline-fueled sad irons after World War II, and the Monitor Sad Iron factory closed in 1954 as electricity relegated most such artifacts to museums and antique shops.

When Mary Florence Potts originally patented her innovative sad iron (today commonly spelled sadiron), she used her name instead of Mrs. Joseph Potts, according to a 2021 “Out of the Attic” article by Julie Martineau of Des Moines County Historical Society (DMCHS).

______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Ironing with Gasoline.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/ironing-with-gasoline. Last Updated: April 1, 2025. Original Published Date: November 5, 2022.