Luling Oil Museum and Crudoleum

Central Texas oil museum preserves the discovery — and folklore — of a giant 1920s oilfield.

A restored 1885 mercantile building downtown, the Luling Oil Museum (formerly the Central Texas Oil Patch Museum) preserves drilling and production equipment from the Luling oilfield of the 1920s. Exhibits educate visitors about the modern petroleum industry.

Known for its tasty BBQ ribs, watermelon seed-spitting contest, and colorfully decorated oil pump jacks, Luling became a petroleum boom town in 1922, when leading citizen Edgar B. Davis discovered a giant oilfield. The oil museum gives little credence to local stories of the giant field being discovered thanks to a famous psychic’s “reading.”

Exhibits in an 1885 Luling mercantile store educate visitors about a 1922 oilfield discovery and the modern petroleum industry. Photo courtesy Luling Oil Museum.

Luling’s oilfield discovery northeast of San Antonio and south of Austin allowed the small town to join recent oil booms already making headlines to the north in Ranger (1917) and Burkburnett (1918). At its peak in 1924, the Luling field had about 400 wells producing more than 11 million barrels of oil.

Years later, new technologies like horizontal drilling helped reinvigorate the central Texas oil patch, according to Carol Voight, a director of the Luling Oil Museum interviewed by an Austin TV news reporter in 2013.

The oil museum, “shows the contrast of the tools and technology of the past with those utilized in the oil industry today,” Voight explained. Exhibits trace the development of the oil industry — from the first U.S. oil well in 1859 in Pennsylvania to the social and economic impact on central Texas.

Downtown Oil Museum

Housed in the 1885 Walker Brothers mercantile store and renovated several times, the Luling Oil Museum building once sold “everything from nails and hammers to ladies’ shoes, to toys,” reported the Lockhart Post-Register in a 2021 article about the renovation. “It was the oldest continually operating mercantile store in Texas until it closed in 1984.”

After its founding in 1990, the museum purchased the building four years later to showcase what made Luling one of the earliest and wildest boom towns in Texas. Renovations have incorporated new heating, ventilation, and air conditioning powered by geothermal wells. Exhibits continue to be added.

“We strive to demonstrate the struggles between the men and women who were the oilfield pioneers and to create a better understanding of the process of oil exploration and production,” noted one volunteer.

“Our collection includes a working model of a modern oil rig, pump jacks, the ‘Oil Tank Theater,’ and an excellent assortment of tools from each decade of the oil industry,” added Voight. To preserve the city’s petroleum heritage, locally donated artifacts show “not only how it was in the olden days,” but also “what can be accomplished with community efforts, cooperation, and creative programs.”

Museum staff in 2015 credited Luling area petroleum companies and service companies like Tracy Perryman, himself a multi-generation independent producer. One of the museum’s great outreach success stories was “Reflections of Texas Art Exhibit.”

Combined with the permanent oil exhibits, the art show attracted more school field trips from San Antonio. Another program was an annual quilt show, which brought another kind of audience into the museum’s oil exhibit spaces. Like many small oil and gas museums, preservation work depends on community support.

In a frugal approach to integrating downtown with outdoor exhibit space, the museum in 2012 partnered with Susan Rodiek, PhD, and graduate students of architectural design at Texas A&M University. Her student teams proposed designs to economically exploit existing facilities while providing new exhibit spaces. Students approached the project competitively, proclaiming the museum their “first client.”

Museum Association Board Member Trey Bailey noted, “The preliminary designs that the Aggie students presented to us were fantastic. There were some terrific concepts, and the work was detailed and quite fascinating.”

Voight added, “They really got it – Luling’s rich heritage in oil, the E.B. Davis story and more. Being able to get this quality of work and vision is tremendous to our efforts to showcase some of the true historic gems of Luling. “Dr. Rodiek and her able team have again offered us the ability to get this project moving, especially considering the limited budget we have at this time.”

Once known as the toughest town in Texas, visitors today flock to Luling on the first Saturday in April for the annual Roughneck BBQ and Chili Cook-Off. — where they have found “Best ribs in the country,” according to Reader’s Digest. Crowds also gather every June for the renowned Watermelon Thump Festival and Seed-Spitting Contest.

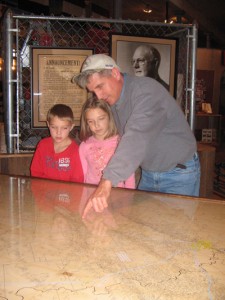

Museum Board Member Trey Bailey and his children examine an oilfield map almost a century after the 1920s Luling boom. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Guinness Book of World Records has documented Luling’s watermelon seed-spitting with a distance of 68 feet, 9 and 1/8 inches, set in 1989. The distance reportedly is still unbeaten.

A Giant Oilfield

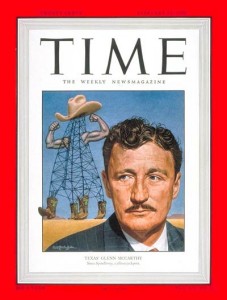

Although the Luling Oil Museum’s historic Walker Brothers building was a center for trading cotton, crude oil replaced cotton in Luling’s future thanks to Edgar B. Davis and his Rafael Rios No. 1 discovery well of August 9, 1922.

After drilling six consecutive dry holes near Luling, Davis’ heavily in debt United North & South Oil Company finally struck “black gold.” The wildcat well revealed an oilfield that proved to be 12 miles long and two miles wide.

After sampling “the best ribs in the country,” visitors to Luling, Texas, marvel at the many decorated pump jacks seen in its historic downtown.

Some people proclaimed that Davis, president of the exploration company, found the town’s oil-rich geologic formation after getting a psychic reading from clairvoyant Edgar Cayce. A geologist working for Davis figured out the oilfield’s likely location.

“Many have called Edgar B. Davis eccentric, and perhaps it was his unconventional personality that led to several half-truths about a career that would be exceptional without embellishment,” noted Riley Froh in a 1979 article in the East Texas Historical Journal.

In the early summer of 1922, Davis was struggling financially when he located the oilfield’s discovery well five miles northwest of Luling. “Drilling on the recommendation of only one geologist and against the advice of several, Davis located his seventh well at random,” Froh reported.

Luling’s downtown museum preserves “the vibrant life and times of ‘the toughest town in Texas’ and the oil boom in the Central Texas oil patch.” Photo courtesy Luling Oil Museum.

By 1924, Luling was a top-producing oilfield in the United States, exceeding the early 1900s fields of southeastern Texas, including Sour Lake and even the world-famous Spindletop Hill.

Exhibits at the Luling Oil Museum focus on the real science behind the discovery, which resulted in the town’s population skyrocketing from less than 500 people to 5,000 people within months after the Rafael Rios No. 1 well.

Psychic Dreams of Oil

Biographers of the once-famous American psychic Edgar Cayce have noted that he found his own mysterious path into exploring the oil patch at Luling. In 1904, Cayce was a 27-year-old photographer when a local newspaper described his “wonderful power that is greatly puzzling physicians and scientific men.”

The Hopkinsville Kentuckian reported that Cayce – from a hypnotic state – could seemingly determine causes of ailments in patients he never met. By 1910, the New York Times proclaimed that “the medical fraternity of the whole country is taking a lively interest in the strange power possessed by Edgar Cayce to diagnose difficult diseases while in a semi-conscious state.”

As his reputation grew, Cayce expanded his photography business with the addition of adjacent rooms and a specially made couch so he could recline to render readings. He became known as “The Sleeping Prophet” while his readings expanded beyond medical diagnoses into reincarnation, dream interpretation, psychic phenomenon…and advising oilmen.

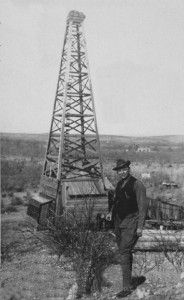

Edgar Cayce visited his drilling site in San Saba County, Texas, in 1921. The once-famous psychic’s abilities failed him searching for oil.

Sidney Kirkpatrick, author of Edgar Cayce: An American Prophet, explained that Cayce in 1919 provided detailed trance revelations to several oilmen probing the prolific Desdemona oilfield in Eastland County, Texas. The results reportedly inspired Cayce and several partners to form their own company.

In September 1920, Cayce became the clairvoyant partner of Cayce Petroleum Company. Guided by his own psychic readings, Cayce Petroleum Company leased some acreage around Luling. Not far away, Edgar B. Davis had drilled eight dry holes and nearly gone broke before completing the discovery well for Luling’s oilfield.

But raising capital for Cayce Petroleum drilling proved difficult and eventually led to loss of the Luling leases. Cayce’s company tried again 150 miles north in San Saba County, Texas, and according to Kirkpatrick’s book, Cayce’s readings included “detailed descriptions given of the various rock geological formations that would be encountered as they drilled.”

Cayce Petroleum’s Rocky Pasture No. 1 well would drill beyond 1,650 feet in search of what Cayce described as a “Mother Pool,” capable of producing 40,000 barrels of oil a day. The psychic’s exploration company did not find any oil, ran out of money, and failed.

Salt Dome Faults

In a 2017 email to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society, long-time AOGHS member Dan Plazak noted Cayce spoke of finding oil at a salt dome at Luling. Petroleum and the geology of salt domes had been in the news since one had been revealed at Spindletop Hill in 1901, thanks to the persistence of Patillo Higgins, “Prophet of Spindletop.”

Plazak, a consulting geologist and engineer, reported that Cayce, “speaking in a trance, proclaimed that oil would be found at Luling associated with a salt dome. But there are no salt domes at Luling, and Cayce’s bad psychic advice could only have prevented Davis from finding oil.

“It was a geologist working for Davis who saw faulting in the outcrop and correctly predicted that the oil would be trapped behind the fault,” Plazak added.

An associate of Cayce, David Kahn, later wrote Davis asking the successful oilman to give some of the Luling profits to Cayce, but Davis declined. “Edgar Davis was famously generous, but his refusal to reward Cayce indicates that he didn’t consider Cayce to have been of much help,” explained Plazak in an email to AOGHS.

However, the geologist added, Davis continued to consult Cayce concerning possible presidential ambitions — Davis had convinced himself he was destined for the White House.

Plazak explained that it was a geologist working for Davis who saw faulting in the outcrop, and correctly predicted that the oil would be trapped behind the fault.

After a few early wells, “Cayce’s oil-exploration readings were a complete bust, both for his own oil company and later for many other oil drillers, in locations all over the country.”

In his email, Plazak — a “geologist and researcher of finding oil with doodlebugs, dreams, and crystal balls” from Colorado — added there are still those today who believe in psychic advice who no doubt are “raising money on the internet to drill yet another dry hole in San Saba County.”

Despite the psychic’s exploration readings not working, investors apparently can still be tempted with promotions of Cayce’s ability to find a “mother pool of oil.” More interesting research from oil patch detective Dan Plazak can be found at Mining Swindles.

A graduate of Michigan Tech and the Colorado School of Mining, Plazak in 2010 wrote “an entertaining and informative volume that delightfully investigates the history of mining frauds in the United States from the Civil War to World War I,” according to his publisher, the University of Utah Press.

“In his estimable work, A Hole in the Ground with a Liar at the Top, Dan Plazak strikes it rich with his examination of the old west’s most successful villains and their crimes.” — Utah Historical Quarterly

Modern “Crudoleum”

Today, the psychic legacy of failed oilman Edgar Cayce lives on at the Association for Research and Enlightenment in Virginia Beach, Virginia, founded in 1931, and “the official world headquarters of the works of Edgar Cayce, considered America’s most documented psychic.”

An invention from Cayce’s venture into the oil business remains on the market — his “pure crude oil” product he recommended as a first step toward replenishing healthy hair. Cayce invented a “pure crude oil” product he called Crudoleum, which is sold today as a cream, shampoo and conditioner. Baar Products Inc. of Downingtown, Pennsylvania, offers Crudoleum Pennsylvania Crude Oil Scalp Treatment.

Learn more U.S. petroleum history by visiting the Luling Oil Museum in the historic Walker Brothers building in downtown Luling.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Texas Art and a Wildcatter’s Dream: Edgar B. Davis and the San Antonio Art League (1998); Drilling Technology in Nontechnical Language

(2012); Edgar Cayce: An American Prophet

(2001); A Hole in the Ground with a Liar at the Top: Fraud and Deceit in the Golden Age of American Mining (2010). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Central Texas Oil Patch Museum.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/energy-education-resources/luling-oil-field. Last Updated: July 31, 2025. Original Published Date: June 21, 2015.