by Bruce Wells | May 19, 2025 | Petroleum History Almanac

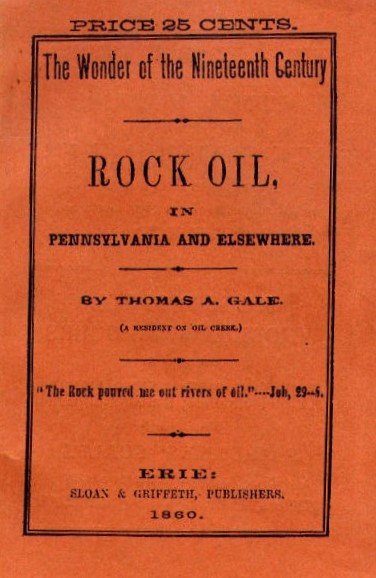

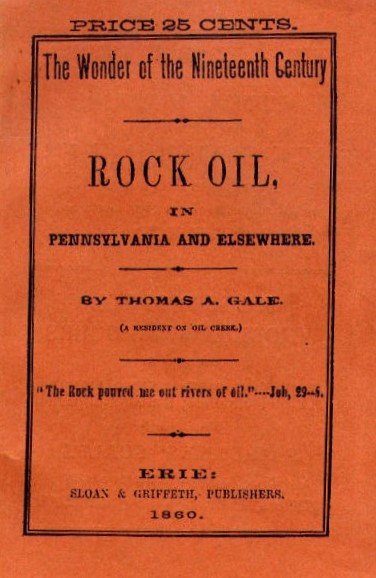

Less than 10 months after Edwin L. Drake and his driller William “Uncle Billy” Smith completed the first commercial U.S. oil well on August 27, 1859, along Oil Creek in Titusville, Pennsylvania, Thomas A. Gale wrote a detailed study about rock oil — and helped launch the petroleum age.

Published in 1860, The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere described a radical fuel source for the popular lamp fuel kerosene, which had been made from coal for more than a decade.

“Those who have not seen it burn may rest assured its light is no moonshine; but something nearer the clear, strong, brilliant light of day,” Gale declared in his 25-cent pamphlet printed in Erie by Sloan & Griffith Company.

Thomas Gale’s 80-page pamphlet in 1860 marked the beginning of the petroleum age, illuminated with kerosene lamps.

“In other words, rock oil emits a dainty light; the brightest and yet the cheapest in the world; a light fit for Kings and Royalists, and not unsuitable for Republicans and Democrats,” Gale added.

Oil in Rocks

Gale’s descriptions of the value of petroleum helped launch investments in new exploration companies, especially as he noted the commercial qualities of Pennsylvania oil for refining into kerosene, the distilled “coal oil” invented in 1848 by Canadian chemist Abraham Gesner.

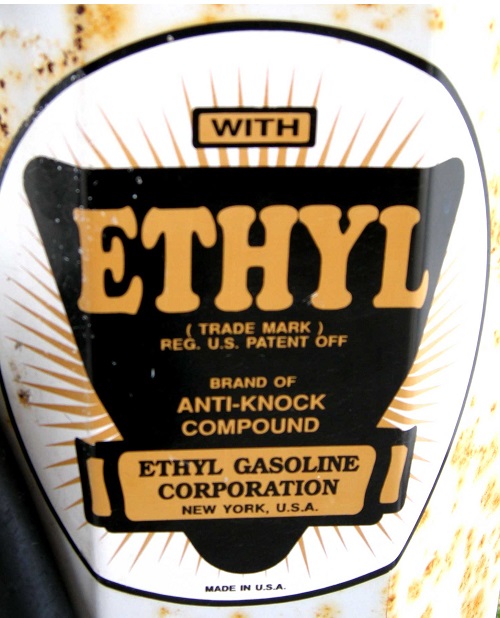

Historians regard the 80-page publication as the first book about America’s petroleum industry. The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere was almost forgotten until 1952, when the Ethyl Corporation of New York republished the work. Only three original copies were known to exist.

“Not by the widest stretch of the imagination could Thomas Gale have realized, when he put down his pen on June 1, 1860, that he had written a book destined to become one of the rarest of all oil books,” proclaimed the Ethyl historian when the company republished Gale’s book.

Ethyl Corporation noted the scarcity of copies of the book had prevented “all but a few historians” from giving the book the attention it deserved.

“Gale wrote his book to satisfy a public desire for more information about petroleum. Newspapers had carried belated accounts of Drake’s discovery well, and the mad scramble for oil that followed, but actually the world knew little about petroleum.”

“The Rock poured…”

The book’s 11 chapters explain practical aspects of the new petroleum industry. Chapters one and two, “What is Rock Oil?” and “Where is the Rock Oil found?” were followed by “Geological Structure of the Oil Region.”

Chapters four through six explained the early technologies (and costs) for pumping the oil, while the next two chapters examine “Uses of Rock Oil.” The final three chapters offered “Sketches of several oil wells,” “History of the Rock Oil Enterprise,” and “Present condition and prospects of Rock Oil interests in different localities.”

Chapter three in The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere features the “geological structure of the oil region,” today part of Oil Creek State Park in northwestern Pennsylvania.

Originally published by Sloan & Griffith of Erie, Pennsylvania, the 1860 cover noted the author as “a resident of Oil Creek” and included a biblical quote, “The Rock poured me out rivers of oil,” from Job, 29:6.

In addition to mysteriously burning gasses and “tar pits,” explorers for millennia have referenced signs of coal, bitumen, and substances very much like petroleum — a word derived from the Latin roots of petra, meaning “rock” and oleum meaning “oil.”

But did Thomas Gayle’s 1860 work produce the first book about oil as Ethyl Corporation historians believed when the company reprinted it in 1952? In fact, there have been many references to natural oil seeps recorded millennia ago (including in the Bible), according to a geologist who has researched the earliest sightings of petroleum.

Illuminating Petroleum

Several years before the 1859 oil discovery in Pennsylvania, businessman George Bissell hired a prominent Yale chemist to study the potential of oil and its products to convince potential investors (see George Bissell’s Oil Seeps).

“Gentlemen, it appears to me that there is much ground for encouragement in the belief that your company have in their possession a raw material from which, by simple and not expensive processes, they may manufacture very valuable products,” reported Benjamin Silliman Jr. in 1855.

Silliman’s groundbreaking “Report on the Rock Oil, or Petroleum, from Venango Co., Pennsylvania, with Special Reference to its Use for Illumination and Other Purposes,” convinced the petroleum industry’s earliest investors to drill at Titusville. Cable-tool technology developed for brine wells would drill the well.

According to historian Paul H. Giddens in the 1939 classic, The Birth of the Oil Industry, Silliman’s 1855 report, “proved to be a turning-point in the establishment of the petroleum business, for it dispelled many doubts about its value.”

The Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company would evolve into the Seneca Oil Company of New Haven, Connecticut, which became America’s first oil company after Drake completed the first U.S. commercial well drilled seeking oil in 1859.

Rock Oil Products

In addition to providing oil for refining into kerosene lamps (and someday rockets), oilfield discoveries led to many products. Early petroleum products included axle greases, an oilfield paraffin balm, and in Easton, Pennsylvania, Crayola crayons.

Further, oil offered an improved asphalt prior to the first U.S. auto show in November 1900 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden.

Ethyl Corporation was established in 1923 by General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey,

Responding to consumer demand for better automobile gasoline, General Motors and Standard Oil of New Jersey established the Ethyl Corporation in 1923. The company initially downplayed the danger of tetraethyl lead. Leaded gas would be banned for use in cars in the 1970s

Importantly, high-octane leaded aviation fuel proved vital for victory in World War II — and the additive still fuels many piston-engine aircraft and racecars.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Wonder of the Nineteenth Century: Rock Oil in Pennsylvania and Elsewhere (1952); The Birth of the Oil Industry (1939); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “First Oil Book of 1860.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/first-oil-book-of-1860. Last Updated: May 17, 2025. Original Published Date: May 31, 2020.

by Bruce Wells | Apr 7, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

April 7, 1902 – Spindletop Boom brings The Texas Company –

Joseph “Buckskin Joe” Cullinan and Arnold Schlaet established The Texas Company in Beaumont to transport and refine oil from Spindletop Hill, a giant oilfield discovered in January 1901. The new company constructed a kerosene refinery in Port Arthur — and discovered an oilfield at Sour Lake Springs, where its Fee No. 3 well produced 5,000 barrels of oil a day in 1903.

The National Route 66 Museum in Elk City, Oklahoma, preserves the heritage of Texaco, the first petroleum company to market products in all 50 states. Photo by Bruce Wells.

The Texas Company telegraph address at its New York office was “Texaco,” a name soon adopted for its petroleum products. In 1909 a red star with a green capital “T” was trademarked and by 1928 the Texaco brand operated more than 4,000 service stations nationwide. The Texas Company, which officially renamed itself Texaco in 1959, was acquired by Chevron in 2001.

Learn more in Sour Lake produces Texaco.

April 7, 1966 – Cold War Accident boosts Offshore Technology

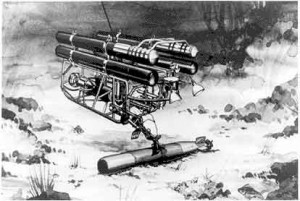

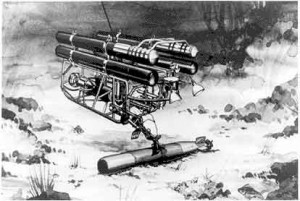

A robotic technology soon adopted by the offshore petroleum industry was first used to retrieve an atomic bomb. America’s first cable-controlled underwater research vehicle (CURV) attached cables to recover the weapon lost in the Mediterranean Sea.

The U.S. Navy in 1966 used its CURV (Cable-Controlled Underwater Recovery Vehicle) to recover a lost nuclear bomb in the Mediterranean.

The 70-kiloton hydrogen bomb, which had been lost when a B-52 crashed off the coast of Spain in January, was safely hoisted from a depth of 2,850 feet.

“It was located and fished up by the most fabulous array of underwater machines ever assembled,” proclaimed Popular Science magazine. During the Cold War, the Navy developed deep-sea technologies that the offshore petroleum industry would adopt and continue to advance.

Learn more in ROV – Swimming Socket Wrench.

April 8, 1929 – Sinclair vs. United States

The Supreme Court unanimously upheld a lower court ruling that Congress had the right to investigate Sinclair Oil founder Harry Sinclair’s personal dealings with Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall regarding the leasing of federal oil reserves. In 1922, Fall had leased land in the Teapot Dome oilfield (Navy Reserve No. 3) to the Mammoth Oil Company, a Sinclair subsidiary. He also leased land in California’s Elk Hills reserve to Edward Doheny, the 1892 discoverer of the Los Angeles Field.

After several trials, proceedings concluded with Doheny being acquitted of conspiracy and Fall convicted of accepting bribes and serving nine months in prison, notes the Federal Judicial Center. He was the first cabinet official to go to prison. Sinclair was acquitted of conspiracy but convicted of contempt of Congress and served six and a half months in prison in 1929.

April 9, 1914 – Ohio Cities Gas Company founded

Beman Dawes and Fletcher Heath organized the Ohio Cities Gas Company in Columbus, Ohio, before building an oil refinery in West Virginia. Ohio Cities Gas acquired Pennsylvania-based Pure Oil Company in 1917 and adopted that name three years later. Pure Oil was founded in Pittsburgh in 1895 by independent oil producers, refiners, and pipeline operators to counter the market dominance of Standard Oil Company.

Ohio Cities Gas Company became Pure Oil in 1917.

By producing, refining and selling its products, Pure Oil became the second vertically integrated petroleum company after Standard Oil. Headquartered in a now iconic Chicago skyscraper it built in 1926, the company joined the 100 largest U.S. industrial corporations. It was acquired in 1965 by Union Oil Company of California, now a division of Chevron.

April 9, 1966 – Birthday of Tula’s Golden Driller

A 76-foot statue of an oilfield worker today known as “The Golden Driller” made its debut at the International Petroleum Exposition in Tulsa, Oklahoma. After several refurbishments, the 22-ton statue would contain 2.5 miles of rods and mesh with tons of plaster and concrete — withstanding winds up to 200 mph. A smaller version of Tulsa’s iconic roughneck originally appeared at the 1953 petroleum exposition as a promotion for the Mid-Continent Supply Company of Fort Worth, Texas.

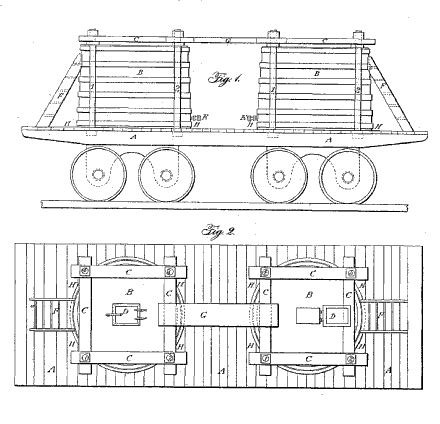

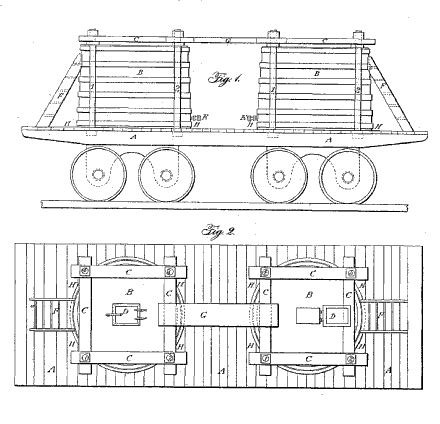

April 10, 1866 – Densmore Brothers patent Railroad Oil Tank Car

James and Amos Densmore of Meadville, Pennsylvania, received a patent for their “Improved Car for Transporting Petroleum,” developed a year earlier in the northwestern Pennsylvania oil regions. Their patent illustrated a simple but sturdy design for securing two re-enforced containers on a typical railroad car.

The Densmore dual tank car briefly revolutionized the bulk transportation of oil to market. Hundreds of the twin tank railroad cars were in use by 1866.

Although the Densmore cars were an improvement, they would be replaced by the more practical single, horizontal tank. After leaving the business, Amos Densmore in 1875 invented a new way for arranging “type writing machines” so commonly used letters would not collide — the “Q-W-E-R-T-Y” keyboard. James Densmore’s continued success in oilfields helped finance the start of the Densmore Typewriter Company.

Learn more in Densmore Brothers invent First Oil Tank Car.

April 11, 1957 – Independent Producer William Skelly dies

William Grove Skelly (1878 -1957) died in Tulsa after a long career as an independent producer he began as a 15-year-old tool dresser in early Pennsylvania oilfields. Prior to World War I, he found success in the El Dorado field outside Wichita, Kansas. Skelly incorporated Skelly Oil Company in Tulsa in 1919. In 1923, Skelly organized the first International Petroleum Exposition while serving as president of the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce. Skelly in 1947 helped establish KWGS, Tulsa’s first FM radio station and one of the earliest educational stations in the nation.

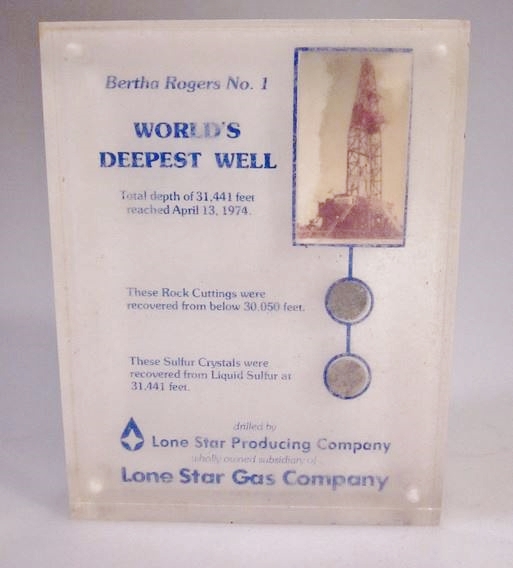

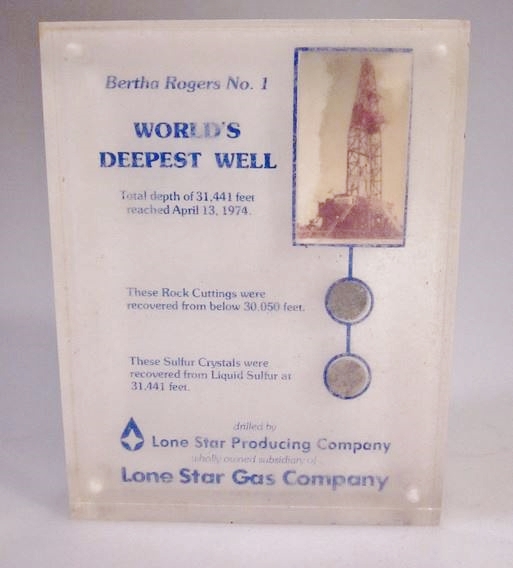

April 13, 1974 – Depth Record set in Oklahoma Anadarko Basin

After drilling for 504 days and spending about $7 million, the Bertha Rogers No. 1 well reached a total depth of 31,441 feet (5.95 miles) before being stopped by liquid sulfur. Drilled in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin, it held the record of the world’s deepest well for more than a decade.

The GHK Company of Robert Hefner III and partner Lone Star Producing Company believed natural gas reserves resided deep in the Anadarko Basin extending across West-Central Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle. Their first high-tech drilling attempt began in 1967 and took two years to reach a then record depth of 24,473 feet.

A 1974 souvenir plaque of the Bertha Rogers No. 1 well, which reached almost six miles deep in Oklahoma’s Anadarko Basin.

The 1969 well found plenty of natural gas, according to historian Robert Dorman, but because of federal price controls, “the sale of the gas could not cover the high cost of drilling so deeply – $6.5 million, as opposed to a few hundred thousand dollars for a conventional well.”

The drilling of the Bertha Rogers well began in November 1972 and averaged about 60 feet per day. By April 1974, bottom-hole pressure reached almost 25,000 pounds per square inch with a temperature of 475 degrees. The well’s 1.5 million pounds of casing was the heaviest ever handled by a drilling rig, and it took eight hours for cuttings to reach the surface.

Learn more in Anadarko Basin in Depth.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Texaco Story: The First Fifty Years, 1902-1952 (2012); Mapping the Deep: The Extraordinary Story of Ocean Science

(2012); Mapping the Deep: The Extraordinary Story of Ocean Science (2002); Diving & ROV: Commercial Diving offshore (2021); The American Railroad Freight Car (1995); Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 (2019); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America

(2002); Diving & ROV: Commercial Diving offshore (2021); The American Railroad Freight Car (1995); Story of the Typewriter, 1873-1923 (2019); Tulsa Where the Streets Were Paved With Gold – Images of America (2000); Oil in Oklahoma

(2000); Oil in Oklahoma (1976); History Of Oil Well Drilling

(1976); History Of Oil Well Drilling (2007). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2007). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

(2009). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.