by Bruce Wells | Dec 29, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

December 30, 1854 – First American Oil Company incorporates –

George Bissell and six investors incorporated the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of New York. Convinced by natural seeps that oil could be produced in northwestern Pennsylvania, Bissell formed this first U.S. petroleum exploration company “to raise, manufacture, procure, and sell Rock Oil” from Hibbard Farm in Venango County. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 18, 2025 | Petroleum Products

How a petroleum product at the bottom of the refining process improved American mobility.

As the U.S. centennial approached, President Ulysses S. Grant directed that Pennsylvania Avenue be paved with asphalt. By 1876, the president’s paving project using Trinidad asphalt covered about 54,000 square yards. (more…)

by Bruce Wells | Dec 10, 2024 | Petroleum History Almanac

Grandfather scouted Philadelphia streets for earliest gas station locations.

Seeking to preserve heirlooms, families often turn to local museums, colleges, and historical societies for help. When related to petroleum business careers, the American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) website maintains updated links to special resources, community oil and gas museums, and some help for researching old oil company stock certificates.

A petroleum industry artifact on the AOGHS Oil & Gas Families page has its own connection with refining history — and is an heirloom in search of an permanent home.

“I have an old Atlantic Richfield brochure that I’d be glad to donate to any interested party,” Jane Benner noted in a June 2022 email to AOGHS. “My grandfather (G.E. Cooper) and his brother (Albert Cooper) as well as a future brother-in-law (W.R. Pierce) are pictured among the staff salesmen and administrators. The handwriting identifying them is that of my grand mother, Eleanor Cooper Benner.”

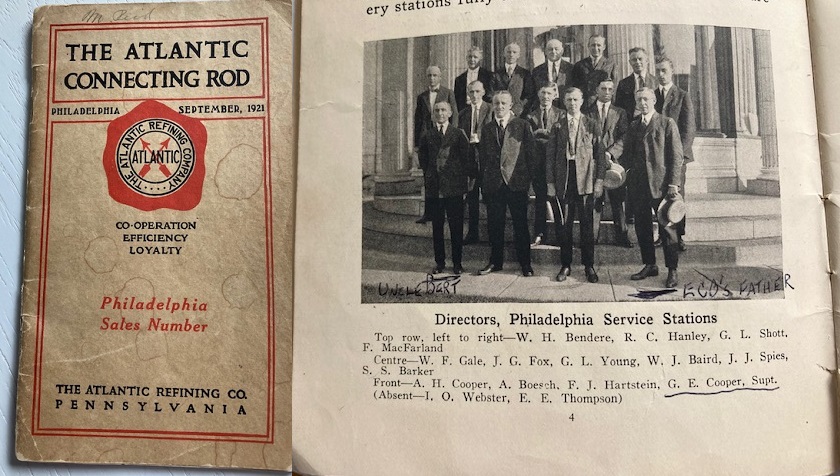

The Atlantic Connecting Rod

Seeking advice for locating a suitable museum or archive, Benner attached the cover and interior photos from her family’s 1921 issue of “The Atlantic Connect Rod” (perhaps an employee publication of the Atlantic Refining Company). The Philadelphia-based venture incorporated in 1870 to refine lamp kerosene and other petroleum products.

Jane Benner’s grandfather George Edward Cooper stands among other Atlantic Refining Company salesmen and administrators in 1921.

Taken over by John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust by the end of the 20th century, Atlantic Refining Company returned as an independent company following the U.S. Supreme Court’s dissolution of the monopoly in 1911.

With its South Philadelphia refinery among the largest in the United States, in 1966 Atlantic Refining merged with Richfield Oil Corporation, creating the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO). Two years later, the new major oil company made the first oil discovery in Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay, leading to construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in the mid-1970s.

Early Philly Gas Stations

“All I know of my grandfather’s work is that he was responsible for identifying locations to open gas stations in Philadelphia (right side of the road, heading out of town, as my mother told me). He died in 1927, so likely his work there was during the 1910s and 1920s,” Benner explained.

The Gulf Refining Company had opened America’s first gas station in Pittsburgh in late 1913, and three years later, the company’s “Good Gulf Gasoline” also went on sale in West Philadelphia.

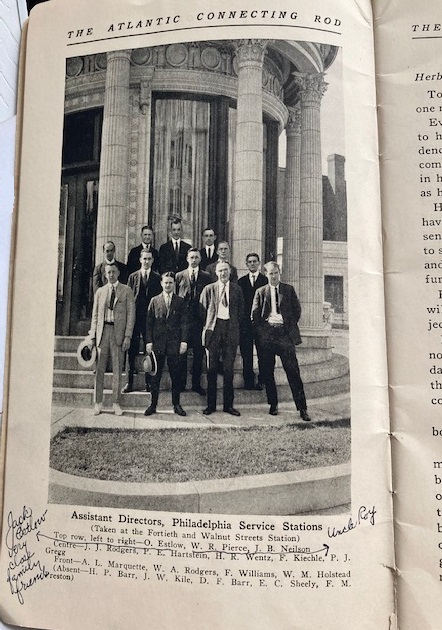

The Atlantic Refining publication features Albert Cooper, brother of Jane Benner’s grandfather, as well as a future brother-in-law (W. R. Pierce). The handwriting identifying them is that of her mother, Eleanor Cooper Benner.

The Gulf station opening at 33rd and Chestnut streets was the start of the “Battle for Gasadelphia,” according to PhillyHistory. In April 1916, Gulf added a second station at at Broad Street and Hunting Park Avenue.

“How did the competition respond? The Philadelphia and Pittsburgh-based Atlantic Refining Company formed a committee to brainstorm,” the 2013 blog noted. Gulf Refining’s first station used a distinctive pagoda style architecture. More designs would emerge to attract consumers.

Both refining companies used service station location and architecture to explore the earliest combinations of integrating functionalism with new or classical designs, noted Keith A. Sculle in his 2004 article, “Atlantic Refining Company’s Monumental Service Stations in Philadelphia, 1917-1919,” published in the Journal of American & Comparative Cultures (see Wiley Online Library).

Preserving Oil History

To find a home for her family’s Atlantic Refining artifact, Benner has been contacting Pennsylvania museums while researching more about the company and her grandfather’s career. She hopes her small but meaningful family heirloom will be preserved as part of America’s petroleum history.

“The booklet is remarkably informative about the company and their sales objectives at that time, including locations and photos of the early stations,” Benner noted in her email to AOGHS. “It’s fine to post my family story, as sparse as it is,” concluded the granddaughter of G.E. Cooper.

Benner added that she planned on contacting curators and archivists at oil museums, “in case anyone is interested.”

_______________________

Recommended Reading: An Illustrated Guide to Gas Pumps (2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Preserving a 1921 Atlantic Refining Publication.” Authors: B.A. Wells and K.L. Wells. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/laviness-family-oilfield-history. Last Updated: July 12, 2022. Original Published Date: July 12, 2022.