by Bruce Wells | Jul 21, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

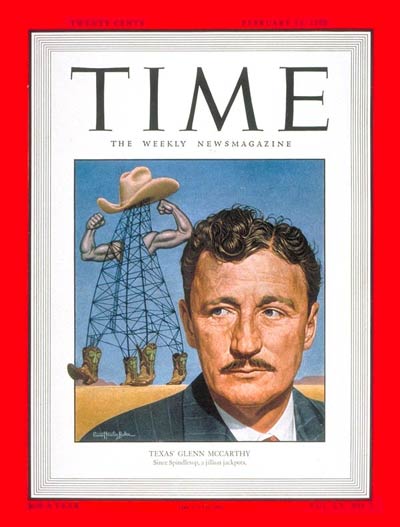

July 21, 1935 – “Diamond Glenn” McCarthy strikes Oil –

Glenn H. McCarthy struck oil 50 miles east of Houston in 1935, extending the already prolific Anahuac field. The well was the first of many for the Texas independent producer who would discover 11 Texas oilfields by 1945.

McCarthy became known as another “King of the Wildcatters” and “Diamond Glenn” by 1950, when his estimated worth reached $200 million ($2 billion today).

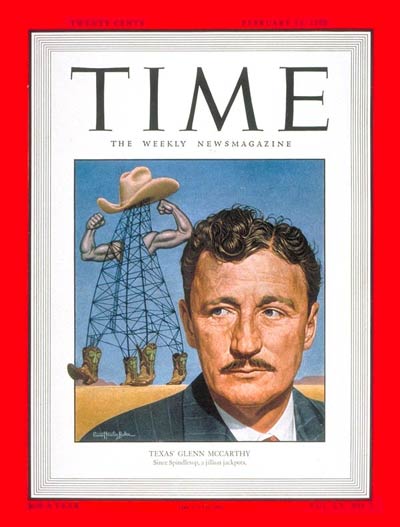

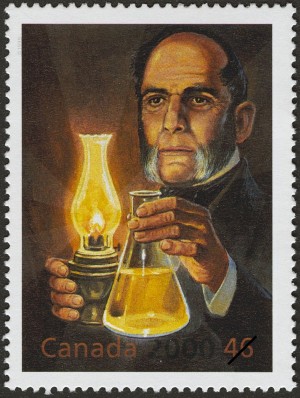

TIME magazine in 1950 featured Texas wildcatter Glenn McCarthy of Houston.

In addition to his McCarthy Oil and Gas Company, McCarthy eventually owned a gas company, a chemical company, a radio station, 14 newspapers, a magazine, two banks, and the Shell Building in Houston. In the late 1940s, he invested $21 million to build the 18-story, 1,100-room Shamrock Hotel — and reportedly spent $1 million on its St. Patrick’s Day 1949 opening gala, which newspapers dubbed “Houston’s biggest party.”

Learn more in “Diamond Glenn” McCarthy.

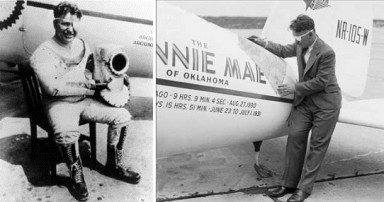

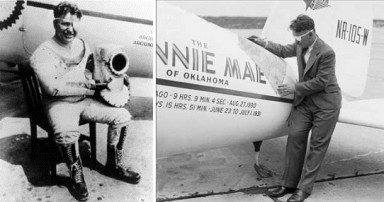

July 22, 1933 – Phillips Petroleum sponsors Flight around the World

Before 50,000 cheering New York City onlookers, former roughneck Wiley Post landed his Lockheed 5C Vega “Winnie Mae,” becoming the first person to fly solo around the world. Post had worked in oilfields near Walters, Oklahoma, when he took his first airplane ride with a barnstormer in 1919 and was inspired to take lessons.

Thanks to a friendship with Frank Phillips, Wiley Post set altitude records and became the first person to fly solo around the world.

In 1926, on the first day of working at a well near Seminole, a metal splinter severely damaged his left eye, causing loss of sight. Post used the $1,700 in compensation to buy his first airplane. He became friends with Frank Phillips, president of Phillips Petroleum, sponsor of several high-altitude experimental flights. Phillips also sponsored the “Woolaroc” — winning plane of an August 1926 air race across the Pacific.

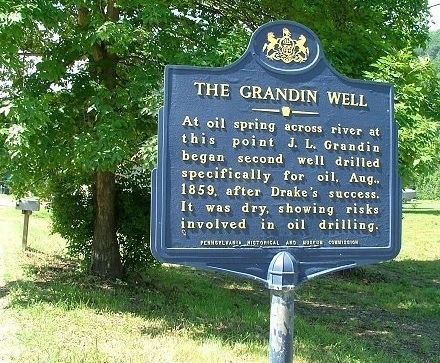

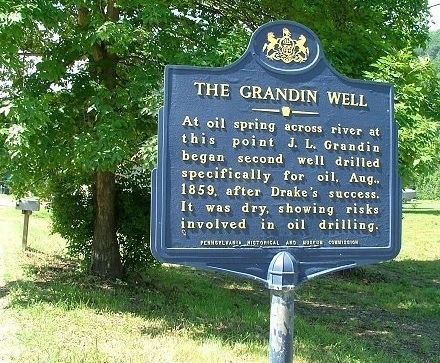

July 22, 1959 – Marker erected for Second U.S. Oil Well

The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission dedicated a state marker to commemorate the man who drilled for oil just a few days after Edwin Drake completed the first U.S. commercial well on August 27, 1859. “After Drake’s discovery of oil in Titusville, some area residents attempted to sink their own well,” noted historians at Explore Pennsylvania. “The vast majority of such efforts failed.”

Pennsylvania historical marker for the 1859 Grandin well — America’s second oil well, which was a dry hole.

Using a simple spring pole, 22-year-old John Grandin and a local blacksmith began to “kick down” a well that would reach almost twice as deep as Drake’s cable-tool depth of 69.5 feet. Despite not finding the oil-producing formation (the Venango Sands), Grandin’s well produced several “firsts” for the young U.S. petroleum industry.

Learn more in First Dry Hole.

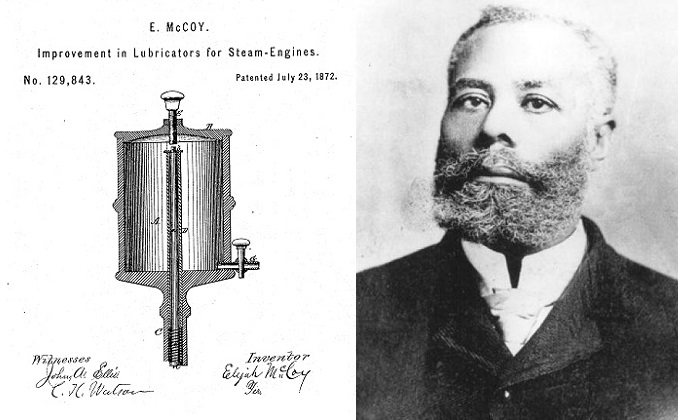

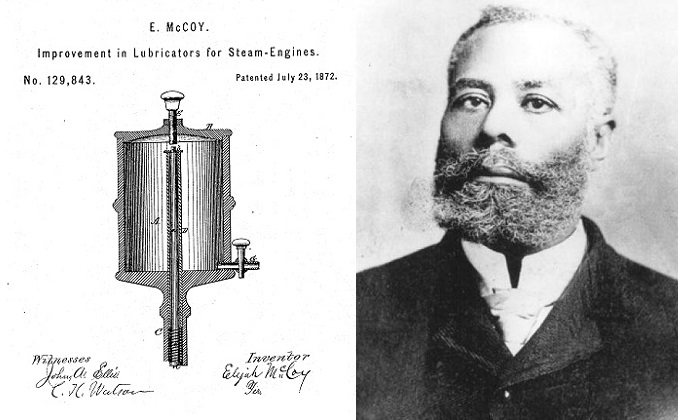

July 23, 1872 – “Real McCoy” Steam-Engine Lubricator

Using petroleum for improving the performance of locomotives became widespread when Elijah McCoy patented an automatic lubricator for steam engines. McCoy designed a device that applied oil through a drip cup to locomotive and ship steam engines. Instead of stopping engines to apply necessary lubrication, McCoy’s device provided it while they ran, saving railroads time and money.

Elijah McCoy invented lubrication systems for steam engines, early beneficiaries of petroleum. Awarded more than 60 patents, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2001.

The Canadian-born McCoy was the son of slaves who had escaped Kentucky. After his family settled in Michigan, 15-year-old McCoy traveled to Scotland to study mechanical engineering. By the time he died in 1929, the inventor had received 60 patents, according to a 1994 Michigan historical marker.

The expression “the real McCoy” reportedly came from railroad engineers not wanting to buy low-quality copycats of his popular device. Before purchasing the lubricator, buyers would ask if it was “the real McCoy.”

July 23, 1951 – Desk & Derrick Clubs organize

After a secretary at Humble Oil and Refining Company organized the first club in New Orleans, the Association of Desk & Derrick Clubs (ADDC) of North America officially began with articles of association signed by the presidents of clubs in Jackson, Mississippi, New Orleans, Los Angeles, and Houston. By 1952, representatives from 40 clubs would attend the first ADDC convention, held at Houston’s Shamrock Hotel.

Learn more in Desk and Derrick Educators.

July 24, 2000 – BP unveils New Green and Yellow Logo

BP — the official name of a group of companies including Amoco, ARCO and Castrol — unveiled a new corporate identity brand, replacing the “Green Shield” logo with a green and yellow sunflower pattern.

The company also introduced a new corporate slogan: “Beyond Petroleum.” When BP — then British Petroleum — merged with Amoco in 1998, the company’s name briefly changed to BP Amoco before all stations converted to the BP brand.

July 25, 1543 – Oil reported in New World

The first documented report of oil in the New World resulted when a storm forced Spanish explorer Don Luis de Moscoso to land two of his brigantines at the mouth of the Sabine River. He had succeeded expedition leader Hernando de Soto and built seven of the small vessels to sail down the newly discovered Mississippi River and westward along the Gulf Coast.

Spanish explorers used brigantines to sail along the Gulf Coast in 1543.

According to an account of the expedition, Indians knew of the future Texas’ natural seeps. “There was found a skumme, which they call Copee, which the Sea casteth up, and it is like Pitch, wherewith in some places, where Pitch is wanting, they pitch their ships; there they pitched their Brigandines.”

Learn more about the first reports of oil worldwide in Earliest Signs of Oil.

July 27, 1918 – Standard Oil of New York launches Concrete Tanker

America’s first concrete vessel designed to carry oil, the Socony, left its shipyard at Flushing Bay, New York. Built for the Standard Oil Company of New York, the barge was 98 feet long with a 32-foot beam and carried oil in six center and two wing compartments, “oil-proofed by a special process,” according to the journal Cement and Engineering News.

Socony, the first concrete oil tanker, launched in 1918. Below is a second version of the oil barge.

“Eight-inch cast iron pipe lines lead to each compartment and the oil pump is located on a concrete pump room aft,” the journal explained. Steel shortages during World War II would lead to the construction of larger reinforced concrete oil tankers.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Big Rich: The Rise and Fall of the Greatest Texas Oil Fortunes (2009); From Oklahoma to Eternity: The Life of Wiley Post and the Winnie Mae

(2009); From Oklahoma to Eternity: The Life of Wiley Post and the Winnie Mae (1998); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(1998); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2009); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage (2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017; Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017; Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

by Bruce Wells | Jun 11, 2025 | Petroleum Technology

Armais Arutunoff designed a downhole centrifugal pump and founded an oilfield service company.

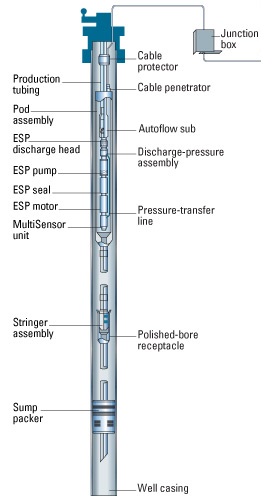

The modern petroleum industry owes a lot to the son of an Armenian soap maker who invented an artificial lift system using an electric motor to drive a centrifugal pump at the well.

With the help of the Phillips Petroleum Company in the 1930s, Armais Sergeevich Arutunoff moved to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and built the earliest practical downhole electric submersible pump. His invention would enhance oilfield production in wells worldwide.

Armais Arutunoff (1893-1978), inventor of the modern electric submersible pump.

A 1936 Tulsa World article described the Arutunoff electric submersible pump (ESP) as “an electric motor with the proportions of a slim fence post which stands on its head at the bottom of a well and kicks oil to the surface with its feet.”

By 1938, an estimated two percent of all oil produced in the United States with artificial lift used an Arutunoff pump (see All Pumped Up – Oilfield Technology).

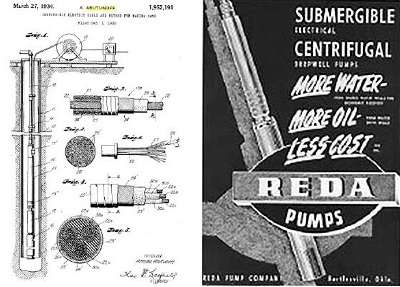

Early Downhole Patents

The first U.S. patent for an oil-related electric pump arrived in the late 19th century during the growth of electrical power generation, according to a 2014 article in the Journal of Petroleum Technology (JPT).

In 1894, a design by Harry Pickett (patent no. 529,804) used a downhole rotary electric motor with “a Yankee screwdriver device to drive a plunger pump.” Expanding Picket’s concept, Robert Newcomb in 1918 received a patent for his “electro-magnetic engine” driving a reciprocating plunger.

“Heretofore, in very deep wells the rod that is connected to the piston, and generally known as the ‘sucker’ rod, very often breaks on account of its great length and strains imposed thereon in operating the piston,” noted Newcomb in his patent application.

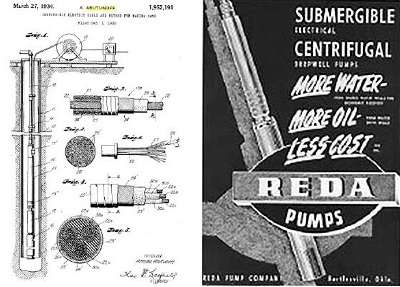

Armais Arutunoff obtained 90 patents, including one in 1934 for an improved well pump and electric cable. At right is a 1951 “submergible” Reda advertisement.

Although several patents followed those of Picket and Newcomb, the Journal reports, “It was not until 1926 that the first patent for a commercial, operatable ESP was issued — to ESP pioneer Armais Arutunoff. The cable used to supply power to the bottomhole unit was also invented by Arutunoff.”

Reda: Russian Electrical Dynamo of Arutunoff

Arutunoff built his first ESP in 1916 in Germany, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. “Suspended by steel cables, it was dropped down the well casing into oil or water and turned on, creating a suction that would lift the liquid to the surface formation through pipes,” reported OHS historian Dianna Everett.

After immigrating to the United States in 1923, in California Arutunoff could not find financial support for manufacturing his pump design. He moved to Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1928 at the urging of a new friend — Frank Phillips, head of Phillips Petroleum Company.

“With Phillips’s backing, he refined his pump for use in oil wells and first successfully demonstrated it in a well in Kansas,” noted Everett. The small company that became Reda Pump manufactured the device.

The name Reda – Russian Electrical Dynamo of Arutunoff – derived from the cable address of the company that Arutunoff originally started in Germany. The inventor would move his family into a Bartlesville home just across the street from Frank Phillips’ mansion.

The founder of Reda Pump once lived in this Bartlesville, Oklahoma, home across from Frank Phillips, whose home today is a museum. Photo courtesy Kathryn Mann, Only in Bartlesville.

A holder of more than 90 patents in the United States, Arutunoff was elected to the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1974. “Try as I may, I cannot perform services of such value to repay this wonderful country for granting me sanctuary and the blessings of freedom and citizenship,” Arutunoff said at the time.

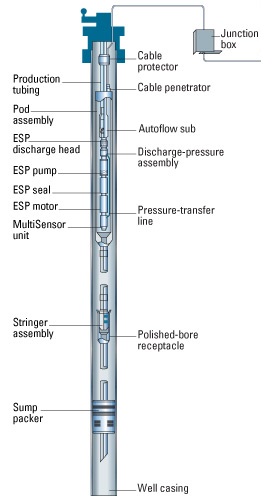

Artificial lift spins the impellers on the pump shaft, putting pressure on the surrounding fluids and forcing them to the surface. Image courtesy Schlumberger.

Arutunoff died in February 1978 in Bartlesville. At the end of the 20th century, Reda ranked as the world’s largest manufacturer of ESP systems. It is now part of Schlumberger.

Armais Sergeevich Arutunoff was born to Armenian parents in Tiflis, part of the Russian Empire, on June 21, 1893. His hometown in the Caucasus Mountains dates back to the 5th Century. His father manufactured soap; his grandfather earned a living as a fur trader.

Centrifugal Pumps

As a young scientist, Arutunoff’s research convinced him that electrical transmission of power could be efficiently applied to oil drilling and improve the production methods he saw in use in the early 1900s in Russia.

Downhole production would require a powerful electric motor, but limitations imposed by the available casing sizes required a new kind of motor.

A small-diameter motor had too little horsepower for the job, Arutunoff discovered. He studied the fundamental laws of electricity seeking answers to how to build a higher horsepower motor exceedingly small in diameter.

By 1916, Arutunoff designed a centrifugal pump to be coupled to the motor for de-watering mines and ships. To develop enough power, the motor needed to run at very high speeds. He successfully designed a centrifugal pump, small in diameter and with stages to achieve high discharge pressure.

Arutunoff designed a motor ingeniously installed below the pump to cool the motor with flow moving up the oil well casing. The entire unit could be suspended in the well on the discharge pipe. The motor, sealed from the well fluid, operated at high speed in the oil.

Although Arutunoff built the first centrifugal pump while living in Germany, he built the first submersible pump and motor in the United States while living in southern California.

Friend of Frank

Arutunoff already had formed Reda to manufacture his idea for electric submersible motors, and after living in Germany, Arutunoff came to the United States with his wife and one-year-old daughter to settle in Michigan, and then Los Angeles.

However, after emigrating to America in 1923, Arutunoff could not find financial support for his downhole production technology. Everyone he approached turned him down, believing his downhole concept impossible under the “laws of electronics.”

No one would consider his inventions until a friend at Phillips Petroleum Company — Frank Phillips — encouraged him to form his own company in Bartlesville. The Arutunoff family moved into a house on the same street as the Phillips home.

Arutunoff’s manufacturing plant in Bartlesville spread over nine acres, employing hundreds during the Great Depression.

In 1928 Arutunoff moved to Bartlesville, where he formed Bart Manufacturing Company, which changed its name to Reda Pump Company in 1930. He soon demonstrated a working model of an oilfield electric submersible pump.

Upside down Motors

One of his pump-and-motor devices produced oil at well in the El Dorado field near Burns, Kansas — the first equipment of its kind to be used downhole. One reporter telegraphed his editor, “Please rush good pictures showing oil well motors that are upside down.”

By the end of the 1930s, Arutunoff’s company held dozens of patents for industrial equipment, leading to decades of success — and still more patents. His “Electrodrill” aided scientists in penetrating the Antarctic ice cap for the first time in 1967.

Arutunoff oilfield technologies had a significant impact on the petroleum industry — quickly proving crucial to successful production for hundreds of thousands of U.S. oil wells.

Also see Conoco & Phillips Petroleum Museums.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: Artificial Lift-down Hole Pumping Systems (1984); Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum

(1984); Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum (2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(2016). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. © 2025 Bruce A. Wells.

Citation Information – Article Title: “Inventing the Electric Submersible Pump.” Author: Aoghs.org Editors. Website Name: American Oil & Gas Historical Society. URL: https://aoghs.org/technology/electric-submersible-pump-inventor. Last Updated: June 12, 2025. Original Published Date: April 29, 2014.

by Bruce Wells | Mar 24, 2025 | This Week in Petroleum History

March 24, 1989 – Exxon Valdez hits Bligh Reef –

After almost 12 years of routine passages by oil tankers through Prince William Sound, Alaska, supertanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef, resulting in an oil spill affecting 1,300 miles of shoreline. Vessels carrying North Slope oil had safely passed through the sound more than 8,700 times.

Eight of Exxon Valdez’s 11 tanks were punctured and an estimated 260,000 barrels of oil spilled, affecting hundreds of miles of coastline. Investigators later found that an error in navigation by the third mate, possibly due to fatigue or excessive workload, had caused the accident.

Shown being towed away from Bligh Reef, the Exxon Valdez had been outside shipping lanes when it ran aground in March 1989. Photo courtesy Erik Hill, Anchorage Daily News.

When the 987-foot tanker hit the reef that night, “the system designed to carry two million barrels of North Slope oil to West Coast and Gulf Coast markets daily had worked perhaps too well,” noted the Alaska Oil Spill Commission. “At least partly because of the success of the Valdez tanker trade, a general complacency had come to permeate the operation and oversight of the entire system.”

Learn more in Exxon Valdez Oil Spill.

March 26, 1930 – “Wild Mary Sudik” makes Headlines

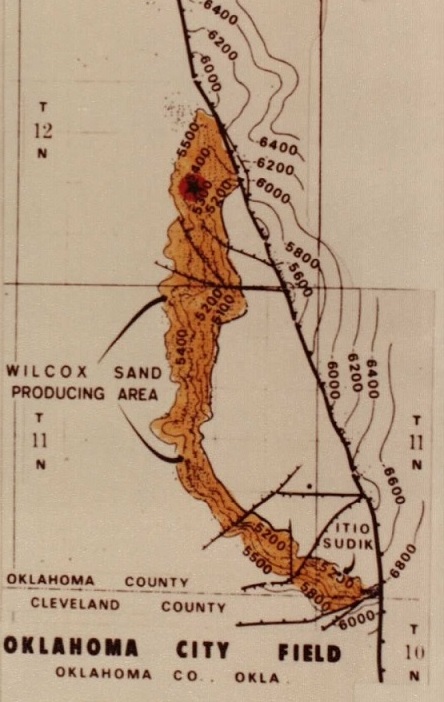

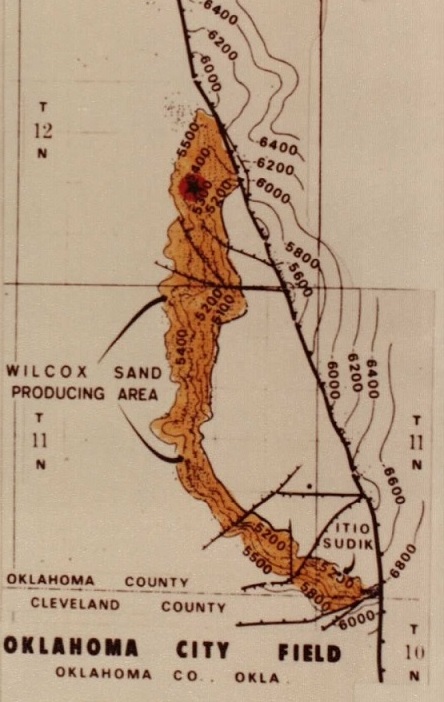

What would become one of Oklahoma’s most famous wells struck a high-pressure formation about 6,500 feet beneath Oklahoma City and oil erupted skyward. The Indian Territory Illuminating Oil Company’s Mary Sudik No. 1 flowed for 11 days before being brought under control. It produced about 20,000 barrels of oil and 200 million cubic feet of natural gas daily, becoming a worldwide sensation.

Highly pressured natural gas from the Wilcox formation proved difficult to control in the prolific Oklahoma City oilfield. Within a week of a 1930 gusher, Hollywood newsreels of it appeared in theaters across America. Photo courtesy Oklahoma History Center.

Efforts to control the well in Oklahoma City’s prolific oilfield (discovered in 1928) were featured on movie newsreels and national radio broadcasts. It was later learned that after drilling more than a mile deep, the exhausted crew did not realize the Wilcox Sand oil formation was permeated with highly pressurized natural gas.

Map of the Wilcox sands formation of the Oklahoma City oilfield in the 1940s.

Although the first ram-type blowout preventer (BOP) had been patented in 1926, deep oil and natural gas fields would take time to tame.

Learn more in “Wild Mary Sudik.”

March 27, 1855 – Canadian Chemist trademarks Kerosene

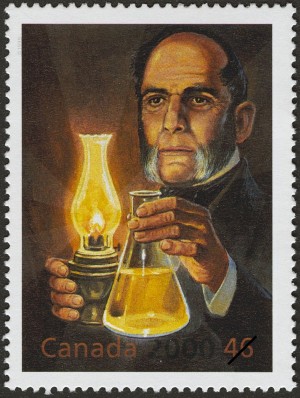

Canadian physician and chemist Abraham Gesner (1797-1864) patented a process to distill coal into kerosene. “I have invented and discovered a new and useful manufacture or composition of matter, being a new liquid hydrocarbon, which I denominate Kerosene,” he proclaimed. Because his new illuminating fluid was extracted from coal, consumers called it “coal oil” as often as kerosene.

On March 17, 2000, Canada issued one million commemorative stamps featuring kerosene inventor Abraham Gesner.

Gesner, considered the father of the Canadian petroleum industry, in 1842 established Canada’s first natural history museum, the New Brunswick Museum, which today houses one of Canada’s oldest geological collections. America’s petroleum industry began when it was learned oil could be distilled into a lamp fuel.

Learn more in Camphene to Kerosene Lamps.

March 27, 1975 – First Pipe laid for Trans-Alaskan Pipeline

With the laying of the first section of pipe in Alaska, construction began on the largest private construction project in American history at the time. Recognized as a landmark of engineering, the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline system, including pumping stations and the Valdez Marine Terminal, would cost $8 billion by the time it was completed in 1977.

Learn more in Trans-Alaska Pipeline History.

March 27, 1999 – Offshore Platform Rocket Launch Test

The Ocean Odyssey, a converted semi-submersible drilling platform, launched a Russian rocket that placed a demonstration satellite into geostationary orbit.

The Zenit-3SL rocket, fueled by liquid oxygen and kerosene rocket fuel, was part of Sea Launch, a Boeing-led consortium of companies from the United States, Russia, Ukraine, and Norway. The platform had once been used by Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) for North Sea exploration.

With an orbital test on March 27, 1999, the Ocean Odyssey, a converted semi-submersible drilling platform, became the world’s first floating equatorial launch pad. Photo courtesy Sea Launch.

“The Sea Launch rocket successfully completed its maiden flight today,” Boeing announced. “The event, which placed a demonstration payload into geostationary transfer orbit, marked the first commercial launch from a floating platform at sea.”

The Sea Launch consortium provided orbital launch services until 2014, when Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula of Ukraine.

Learn more in Offshore Rocket Launcher.

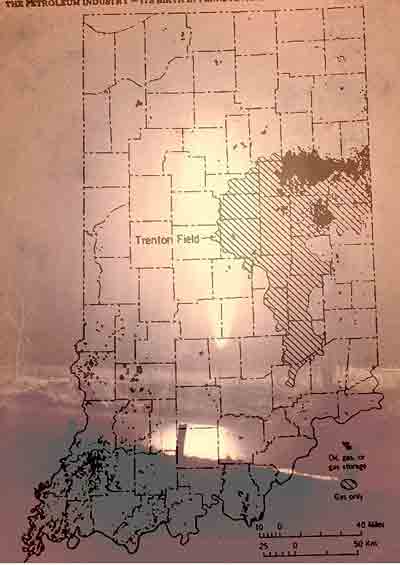

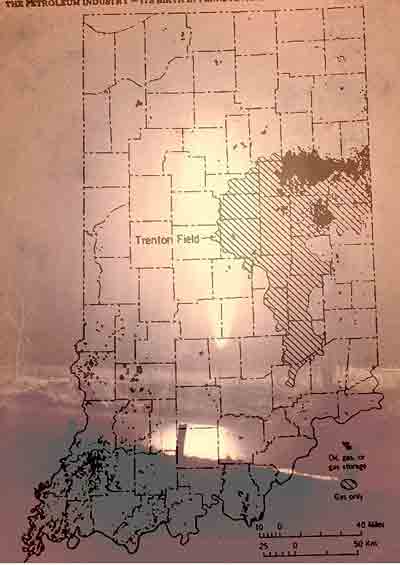

March 28, 1886 – Natural Gas Boom begins in Indiana

Petroleum exploration companies converged on Portland, Indiana, after the Eureka Gas and Oil Company discovered a natural gas field after drilling just 700 feet deep. The well began producing two months after a spectacular natural gas well about 100 miles to the northeast — the “Great Karg Well” of Findlay, Ohio.

According to industrialist Andrew Carnegie, natural gas daily replaced 10,000 tons of coal for making steel.

Portland foundry owner Henry Sees had followed the news from Findlay. He persuaded local investors to drill for Indiana natural gas. In western Pennsylvania, reserves found near Pittsburg had encouraged industrialists there to replace their coal-fired steel and glass foundries with the first large-scale industrial use of natural gas.

Indiana would become the world’s largest natural gas producer, thanks to its Trenton limestone stretching more than 5,100 square miles across 17 counties. Within three years, more than 200 companies were drilling, distributing, and selling natural gas.

Learn more in Indiana Natural Gas Boom.

March 28, 1905 – Oil Discovered in North Louisiana

A small oil discovery in Caddo Parish launched a drilling boom in northern Louisiana and brought economic prosperity to Oil City. The Offenhauser No. 1 well was completed at a depth of 1,556 feet, but yielded just five barrels of oil a day and was abandoned. Far more productive wells quickly followed as the Caddo-Pine Island oilfield 20 miles northwest of Shreveport expanded into 80,000 acres.

The Shreveport Chamber of Commerce in 1955 dedicated a 40-foot monument commemorating the 50th anniversary of oil in Caddo Parish. Photo by Bruce Wells.

“This part of Louisiana, of course, was built on the oil and gas industry, and those visitors interested in the technical aspects of oilfield work will find the museum particularly appealing,” notes the Louisiana State Oil and Gas Museum (formerly the Caddo-Pine Island Oil and Historical Museum). More oilfield history can be found in Shreveport, where natural gas was discovered in 1870 — thanks to an ice plant’s water well. To discourage natural gas flaring, Louisiana passed its first conservation law in 1906.

Learn more in Louisiana Oil City Museum.

March 29, 1819 – Birthday of Father of the Petroleum Industry

Edwin Laurentine Drake (1819-1880) was born in Greenville, New York. Forty years later, he used a steam-powered cable-tool rig to drill the first commercial U.S. oil well at Titusville, Pennsylvania. The former railroad conductor overcame many financial and technical obstacles to make “Drake’s Folly” a milestone in U.S. petroleum history.

Edwin L. Drake (1819-1880) invented a method of driving a pipe down to protect the integrity of the first U.S. oil well. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum.

Drake pioneered using iron casing to isolate his well from nearby Oil Creek. “In order to overcome the hurdles before him, he invented a ‘drive pipe’ or ‘conductor,’ an invention he unfortunately did not patent,” noted historian Urja Davé in 2008. “Mr. Drake conceived the idea of driving a pipe down to the rock through which to start the drill.”

Determined to find oil for refining into kerosene, Drake drilled near natural seeps and found oil on August 27, 1859, at a depth of 69.5 feet at a site today on the grounds of the Drake Well Museum.

Learn more in Edwin Drake and his Oil Well.

March 29, 1938 – Magnolia Oilfield found in Arkansas

“Kerlyn Wildcat Strike In Southern Arkansas is Sensation of the Oil Country,” proclaimed the local newspaper when a well drilled by Kerlyn Oil Company revealed the 100-million-barrel Magnolia oilfield, adding to the 1920s giant oilfield discoveries at El Dorado and Smackover.

Drilling on the Barnett No. 1 well had been suspended because of a lack of money, but geologist and company Vice President Dean McGee urged drilling deeper. He was rewarded with a giant oilfield discovery at the depth of 7,650 feet. McGee later would become an industry pioneer in offshore exploration.

Visit the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in Smackover.

March 30, 1980 – Deadly North Sea Gale

Massive waves during a North Sea gale capsized a floating apartment for Phillips Petroleum Company workers, killing 123 people. The Alexander Kielland platform, 235 miles east of Dundee, Scotland, housed 208 men who worked on a nearby rig in the Ekofisk field. Most of the Phillips workers were from Norway. The platform, converted from a semi-submersible drilling rig, served as overflow accommodation for the Phillips production platform 300 yards away.

_______________________

Recommended Reading: The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, Perspectives on Modern World History (2011); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry

(2011); The Oklahoma Petroleum Industry (1980); Oil Lamps The Kerosene Era In North America

(1980); Oil Lamps The Kerosene Era In North America (1978); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier

(1978); Amazing Pipeline Stories: How Building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Transformed Life in America’s Last Frontier (1997); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(1997); The Extraction State, A History of Natural Gas in America (2021); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry (2009); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History

(2009); Texas Oil and Gas, Postcard History (2013); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946

(2013); Early Louisiana and Arkansas Oil: A Photographic History, 1901-1946 (1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

(1982). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.

_______________________

The American Oil & Gas Historical Society (AOGHS) preserves U.S. petroleum history. Please become an AOGHS annual supporter and help maintain this energy education website and expand historical research. For more information, contact bawells@aoghs.org. Copyright © 2025 Bruce A. Wells. All rights reserved.

(2009); From Oklahoma to Eternity: The Life of Wiley Post and the Winnie Mae

(1998); Myth, Legend, Reality: Edwin Laurentine Drake and the Early Oil Industry

(2009); Western Pennsylvania’s Oil Heritage

(2008); Trek of the Oil Finders: A History of Exploration for Petroleum (1975); Anomalies, Pioneering Women in Petroleum Geology, 1917-2017; Breaking the Gas Ceiling: Women in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry (2019). Your Amazon purchase benefits the American Oil & Gas Historical Society. As an Amazon Associate, AOGHS earns a commission from qualifying purchases.